Russian Genitive Iv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does English Have a Genitive Case? [email protected]

2. Amy Rose Deal – University of Massachusetts, Amherst Does English have a genitive case? [email protected] In written English, possessive pronouns appear without ’s in the same environments where non-pronominal DPs require ’s. (1) a. your/*you’s/*your’s book b. Moore’s/*Moore book What explains this complementarity? Various analyses suggest themselves. A. Possessive pronouns are contractions of a pronoun and ’s. (Hudson 2003: 603) B. Possessive pronouns are inflected genitives (Huddleston and Pullum 2002); a morphological deletion rule removes clitic ’s after a genitive pronoun. Analysis A consists of a single rule of a familiar type: Morphological Merger (Halle and Marantz 1993), familiar from forms like wanna and won’t. (His and its contract especially nicely.) No special lexical/vocabulary items need be postulated. Analysis B, on the other hand, requires a set of vocabulary items to spell out genitive case, as well as a rule to delete the ’s clitic following such forms, assuming ’s is a DP-level head distinct from the inflecting noun. These two accounts make divergent predictions for dialects with complex pronominals such as you all or you guys (and us/them all, depending on the speaker). Since Merger operates under adjacency, Analysis A predicts that intervention by all or guys should bleed the formation of your: only you all’s and you guys’ are predicted. There do seem to be dialects with this property, as witnessed by the American Heritage Dictionary (4th edition, entry for you-all). Call these English 1. Here, we may claim that pronouns inflect for only two cases, and Merger operations account for the rest. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Introduction to Gothic

Introduction to Gothic By David Salo Organized to PDF by CommanderK Table of Contents 3..........................................................................................................INTRODUCTION 4...........................................................................................................I. Masculine 4...........................................................................................................II. Feminine 4..............................................................................................................III. Neuter 7........................................................................................................GOTHIC SOUNDS: 7............................................................................................................Consonants 8..................................................................................................................Vowels 9....................................................................................................................LESSON 1 9.................................................................................................Verbs: Strong verbs 9..........................................................................................................Present Stem 12.................................................................................................................Nouns 14...................................................................................................................LESSON 2 14...........................................................................................Strong -

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Genitive Case

GENITIVE CASE The Genitive is the third and last case existing in both English and Latin. In English, all pronouns have a genitive case that shows possession: "his", "her", "my", "their", "whose", etc. These answer the question "Belonging to whom or what?" Regular nouns in English also have a genitive form: in the singular, the ending "'s" is added; in the plural, s'. Consider the following examples: Their father is here. The man's father is here. The boys' father is here. In Latin, the Genitive case may also show possession. However, it may be used for some other things as well, as you will see later on. It's ending of course varies depending on the original ending of the noun: for a-nouns, the singular is -ae and the plural is -ārum; for both us- and um-nouns, the singular is -ī and the plural is - ōrum. Consider the following chart: Nominative, Accusative, and Genitive Cases a-nouns us-nouns um-nouns sg. pl. sg. pl. sg. pl. Nominative a ae us ī um a Accusative Genitive ae ārum ī ōrum ī ōrum A genitive is normally paired with another noun in the sentence which it modifies. In English, it is always placed immediately before the noun it modifies: for example, "my soup", "the boy's shirt", etc. But in Latin, a genitive may be placed either before or after the noun it modifies: for example, feminae panes, panes feminae. In fact, a genitive may occasionally even be separated by another word: panes sunt feminae. Also, keep in mind that the grammatical possession that the genitive case signifies is a fairly broad and vague connection. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

Russian Case Morphology and the Syntactic Categories David Pesetsky (MIT)1 • Terminology: I Will Use the Abbreviations NGEN, DNOM, VACC, PDAT, Etc

Russian case morphology and the syntactic categories David Pesetsky (MIT)1 • Terminology: I will use the abbreviations NGEN, DNOM, VACC, PDAT, etc. to remind us of the traditional names for the cases whose actual nature is simply N, D, V, and 1. Introduction (types of) P. The case-name suffixes to these designations are thus present merely for our convenience. • Case morphology: Russian nouns, adjectives, numerals and demonstratives bear case Genitive: The most unusual aspect of the proposal will be the treatment of genitive as suffixes. The shape of a given case suffix is determined by two factors: N -- with which I will begin the discussion in the next section. 1. its morphological environment (properties of the stem to which the suffix attaches; e.g. declension class, gender, animacy, number) ; and • Syntax: The treatment of case as in (1) will depend on two ideas that are novel in the context of a syntax based on external and internal Merge, but are also revivals of well- 2. its syntactic environment. known older proposals, as well as a third important concept: The traditional cross-classification of case suffixes by declension-class and by case- name (nominative, genitive, etc.) reflects these two factors. 1. Morphology assignment: When [or a projection of ] merges with and assigns an affix, the affix is copied α α β α • Specialness of the standard case names: Traditionally, the cases are called by onto β and realized on the (accessible) lexical items dominated by β. special names (nominative, genitive, etc.) not used outside the description of case- systems. The specialness of case terminology reflects what looks like a complex This proposal revives the notion of case assignment (Vergnaud (2006); Rouveret & relation between syntactic environment and choice of case suffix. -

Structural Case in Finnish

Structural Case in Finnish Paul Kiparsky Stanford University 1 Introduction 1.1 Morphological case and abstract case The fundamental fact that any theory of case must address is that morphological form and syntactic function do not stand in a one-to-one correspondence, yet are systematically related.1 Theories of case differ in whether they define case categories at a single structural level of representation, or at two or more levels of representation. For theories of the first type, the mismatches raise a dilemma when morphological form and syntactic function diverge. Which one should the classification be based on? Generally, such single-level approaches determine the case inventory on the basis of morphology using paradigmatic contrast as the basic criterion, and propose rules or constraints that map the resulting cases to grammatical relations. Multi-level case theories deal with the mismatch between morphological form and syntactic function by distinguishing morphological case on the basis of form and abstract case on the basis of function. Approaches that distinguish between abstract case and morphological case in this way typically envisage an interface called “spellout” that determines the relationship between them. In practice, this outlook has served to legitimize a neglect of inflectional morphol- ogy. The neglect is understandable, for syntacticians’ interest in morphological case is naturally less as a system in its own right than as a diagnostic for ab- stract case and grammatical relations. But it is not entirely benign: compare the abundance of explicit proposals about how abstract cases are assigned with the minimal attention paid to how they are morphologically realized. -

A Grammar Checker for Challenging Cases

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2021 PLPrepare: A Grammar Checker for Challenging Cases Jacob Hoyos East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Computational Linguistics Commons, Computer Sciences Commons, Morphology Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Hoyos, Jacob, "PLPrepare: A Grammar Checker for Challenging Cases" (2021). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3898. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3898 This Dissertation - unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PLPrepare: A Grammar Checker for Challenging Cases ________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Computing East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Computer Science, Applied Computer Science ______________________ by Jacob Hoyos May 2021 _____________________ Dr. Ghaith Husari, Chair Dr. Brian Bennett Dr. Christopher Wallace Keywords: natural language processing, dependency parsing, foreign language education, arbitrary cases, rule-based morphology detection, hybrid grammar checking ABSTRACT PLPrepare: A Grammar Checker for Challenging Cases by Jacob Hoyos This study investigates one of the Polish language’s most arbitrary cases: the genitive masculine inanimate singular. It collects and ranks several guidelines to help language learners discern its proper usage and also introduces a framework to provide detailed feedback regarding arbitrary cases. -

Case Chapter

by David Pesetsky (MIT) & Esther Torrego (UMass/Boston) draft of a chapter to appear in C. Boeckx (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Minimalism Case 1. Introduction The Minimalist Program includes the important conjecture that all (or most) properties of syntactic computation in natural language should be understood as arising from either (1) the interactions of independent mental systems or (2) "general properties of organic systems" (Chomsky (2001a)). The study of case morphology and the distribution of nominal expressions in the languages of the world is one of the areas in which generative syntax has made the most profound advances over previous approaches. A large (and increasing) number of studies have identified patterns and principles of great generality — achievements that also shed light on other topics and puzzles. At the same time, it is fair to say that the phenomenon of case represents one of the more outstanding challenges for the Minimalist conjecture. Though case is indeed an area in which complex phenomena can be predicted on the basis of more general principles, these principles themselves look quite specific to syntax and morphology, with little apparent connection to external cognitive systems (not to mention general properties of organic systems). Our discussion in this chapter reflects the provisional character of the investigation. 2. Case Theory in Government-Binding Syntax By the late 1970s, it had become clear that the distribution of nominals is governed by special laws cross-linguistically. Though Chomsky and Lasnik (1977) had assembled a structured list of syntactic contexts in which NPs in languages like English are either disallowed or heavily restricted, it remained an open question why these restrictions should hold. -

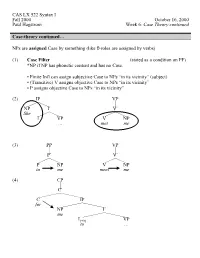

Case Theory Continued

CAS LX 522 Syntax I Fall 2000 October 16, 2000 Paul Hagstrom Week 6: Case Theory continued Case-theory continued… NPs are assigned Case by something (like θ-roles are assigned by verbs) (1) Case Filter (stated as a condition on PF) *NP if NP has phonetic content and has no Case. • Finite Infl can assign subjective Case to NPs “in its vicinity” (subject) • (Transitive) V assigns objective Case to NPs “in its vicinity” • P assigns objective Case to NPs “in its vicinity” (2) IP VP 31 NP I′ V′ She 33 IVP VNP ... met me (3) PP VP 11 P′ V′ 33 PNP VNP to me meet me (4) CP 1 C′ qp CIP for qp NP I′ me qp I[–fin] VP to … (5) Government α governs β iff i) α is an X° category (that is, α is a head) ii) α c-commands β iii) Minimality is respected. (6) C-command α c-commands β iff i) the first branching node dominating α also dominates β ii) α does not dominate β. (7) Minimality Condition In the configuration [XP … X … [YP … Y … ZP …] …] X does not govern ZP. (8) ... 3 X YP X does not govern ZP. 3 Spec Y′ Y does govern ZP (it’s closer). 3 YZP ... In English, there appears to be an additional constraint: An NP can only receive Case if it is (string) adjacent to the Case-assigner. (9) a. * John makes frequently mistakes. b. John frequently makes mistakes. Another thing that an adjacency requirement can explain is the order of the complements in ditransitive verbs: (10) a. -

Case Endings in Standard Arabic

فرباير م Case Endings in Standard Arabic 1 Dr. Mohammed Ali Mohammed Qarabesh Abstract This study aims briefly at describing and analyzing some aspects of Case endings in Standard Arabic. This is because that Case seems to play a significant role in the grammar of not only Arabic but also in the grammar of many other languages. Many readers of this study might be wondering what Case is and why it is being dealt with.2 In order to comprehend the notion of Case in Arabic, it is necessary to consider the language in which word order is not as stable as it is in the case of English. In Arabic, an NP must have one of three Cases: nominative (NOM), accusative (ACC), or genitive (GEN) according to its position in a sentence. Many learners of Arabic as native or foreign speakers of the language may have no clear idea about Case system in the language. The rules of Case help these learners understand the proper structure of the language. Therefore, a distinction between three types of Case, i.e., Nominative Case, Accusative Case and Genitive Case, is to be dealt with for Arabic lexical NPs. 1 Assistant Professor of Linguistics & Phonetics, Head of English Department, Faculty of Education & Science - Rada’a, Al-Baydha University. 2 Case is the notion of grammar which is usually written with a capital letter ‘C’ as ‘Case’ to be distinguished from the ordinary word ‘case’. 29621 فرباير م Questions of the Study In order to be familiar with the nature of nominal Case and its mechanism in the structure of Arabic sentences, this research study seeks the answer for the following questions: 1.