Rendering the German Dative Case Into Arabic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does English Have a Genitive Case? [email protected]

2. Amy Rose Deal – University of Massachusetts, Amherst Does English have a genitive case? [email protected] In written English, possessive pronouns appear without ’s in the same environments where non-pronominal DPs require ’s. (1) a. your/*you’s/*your’s book b. Moore’s/*Moore book What explains this complementarity? Various analyses suggest themselves. A. Possessive pronouns are contractions of a pronoun and ’s. (Hudson 2003: 603) B. Possessive pronouns are inflected genitives (Huddleston and Pullum 2002); a morphological deletion rule removes clitic ’s after a genitive pronoun. Analysis A consists of a single rule of a familiar type: Morphological Merger (Halle and Marantz 1993), familiar from forms like wanna and won’t. (His and its contract especially nicely.) No special lexical/vocabulary items need be postulated. Analysis B, on the other hand, requires a set of vocabulary items to spell out genitive case, as well as a rule to delete the ’s clitic following such forms, assuming ’s is a DP-level head distinct from the inflecting noun. These two accounts make divergent predictions for dialects with complex pronominals such as you all or you guys (and us/them all, depending on the speaker). Since Merger operates under adjacency, Analysis A predicts that intervention by all or guys should bleed the formation of your: only you all’s and you guys’ are predicted. There do seem to be dialects with this property, as witnessed by the American Heritage Dictionary (4th edition, entry for you-all). Call these English 1. Here, we may claim that pronouns inflect for only two cases, and Merger operations account for the rest. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Introduction to Gothic

Introduction to Gothic By David Salo Organized to PDF by CommanderK Table of Contents 3..........................................................................................................INTRODUCTION 4...........................................................................................................I. Masculine 4...........................................................................................................II. Feminine 4..............................................................................................................III. Neuter 7........................................................................................................GOTHIC SOUNDS: 7............................................................................................................Consonants 8..................................................................................................................Vowels 9....................................................................................................................LESSON 1 9.................................................................................................Verbs: Strong verbs 9..........................................................................................................Present Stem 12.................................................................................................................Nouns 14...................................................................................................................LESSON 2 14...........................................................................................Strong -

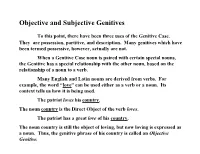

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Genitive Case

GENITIVE CASE The Genitive is the third and last case existing in both English and Latin. In English, all pronouns have a genitive case that shows possession: "his", "her", "my", "their", "whose", etc. These answer the question "Belonging to whom or what?" Regular nouns in English also have a genitive form: in the singular, the ending "'s" is added; in the plural, s'. Consider the following examples: Their father is here. The man's father is here. The boys' father is here. In Latin, the Genitive case may also show possession. However, it may be used for some other things as well, as you will see later on. It's ending of course varies depending on the original ending of the noun: for a-nouns, the singular is -ae and the plural is -ārum; for both us- and um-nouns, the singular is -ī and the plural is - ōrum. Consider the following chart: Nominative, Accusative, and Genitive Cases a-nouns us-nouns um-nouns sg. pl. sg. pl. sg. pl. Nominative a ae us ī um a Accusative Genitive ae ārum ī ōrum ī ōrum A genitive is normally paired with another noun in the sentence which it modifies. In English, it is always placed immediately before the noun it modifies: for example, "my soup", "the boy's shirt", etc. But in Latin, a genitive may be placed either before or after the noun it modifies: for example, feminae panes, panes feminae. In fact, a genitive may occasionally even be separated by another word: panes sunt feminae. Also, keep in mind that the grammatical possession that the genitive case signifies is a fairly broad and vague connection. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

Dative Case What Are the Main Contexts in Which the Dative Case Is Used? What Are the Forms of the Dative Case for Nouns in the Singular and Plural?

Dative Case What are the main contexts in which the dative case is used? What are the forms of the dative case for nouns in the singular and plural? One of the most frequent uses of the dative is as the indirect object of a verb. The indirect object is usually a person or animate being that is the recipient in an agent-object-recipient transaction. We can think of a typical “giving” scenario in which someone (an agent or doer of an action) gives an object to someone else (the recipient). The Czech dative is used to mark the recipient of the object. We have indirect objects in all kinds of English sentences, but the most we do to mark them is put a preposition (to or for) in front of them: Jakub gave Honza a puppy (Jakub gave a puppy to Honza), David made tea for his friends, Lidka bought her mother flowers (She bought flowers for her mother), The teacher lent the student a book, Did you send a postcard also to your parents?… Czech datives overlap with many English indirect objects and are used in much the same way. Some examples: Jakub dal Honzovi pejska. nom: Honza gave puppy David uvařil kamarádům čaj. nom pl: kamarádi boiled tea Lidka koupila mamince květiny. nom: maminka bought flowers Učitelka půjčila žákyni knihu. nom: žákyně lent student Poslal jsi pohled i rodičům? nom pl: rodiče did-you-send postcard also parents When you learn a new verb in Czech, ask yourself (or your teacher, if you’re not sure) if it’s a verb that requires the dative case and add that information to your flashcard for that verb. -

The Special Datives

The Special Datives To this point, the functions of the Dative Case have been 1. Indirect Object of give, tell, show verbs 2. Dative with Special Adjectives friendly to, unfriendly to, similar to, dissimilar to, equal to, suitable for, near to, dear to, pleasing to, etc. 3. Dative with Special Intransitive Verbs parco, mando, impero, noceo, resisto, studeo, etc. 4. Dative with Certain Compound Verbs praesum, praeficio, occurro, etc. (often verbs with prefixes of ob- and prae-) Two new Dative Case functions, sometimes called Special Datives, are explained in Unit XIII. These are the Dative of Purpose and the Dative of Reference. 1. Dative of Purpose. Sometimes, the idea of purpose can be stated in a single noun. In such a case, the Dative Case form of the noun is used. It answers the question, “For what purpose does something exist?” Note how we often ask, “What is that for?” The consul donated money for a reward. Consul pecuniam praemio donavit. Seven common Latin nouns are often used as (for?!) the Dative of Purpose: Principal Parts Dative Singular Form Meaning cura, -ae, f. curae for a concern auxilium, -I, n. auxilio for a help impedimentum, -I, n. impedimento for an obstacle praemium, -I, n. praemio for a reward praesidium, -I, n. praesidio for a guard subsidium, -I, n. subsidio for a support usus,, -us, m. usui for a use NOTA BENE: These are not the only nouns which may be used for purpose; they are only the most common. Sometimes a plural Dative Case form is used for purpose. Catullus poeta scripsit puellas esse curis. -

Russian Case Morphology and the Syntactic Categories David Pesetsky (MIT)1 • Terminology: I Will Use the Abbreviations NGEN, DNOM, VACC, PDAT, Etc

Russian case morphology and the syntactic categories David Pesetsky (MIT)1 • Terminology: I will use the abbreviations NGEN, DNOM, VACC, PDAT, etc. to remind us of the traditional names for the cases whose actual nature is simply N, D, V, and 1. Introduction (types of) P. The case-name suffixes to these designations are thus present merely for our convenience. • Case morphology: Russian nouns, adjectives, numerals and demonstratives bear case Genitive: The most unusual aspect of the proposal will be the treatment of genitive as suffixes. The shape of a given case suffix is determined by two factors: N -- with which I will begin the discussion in the next section. 1. its morphological environment (properties of the stem to which the suffix attaches; e.g. declension class, gender, animacy, number) ; and • Syntax: The treatment of case as in (1) will depend on two ideas that are novel in the context of a syntax based on external and internal Merge, but are also revivals of well- 2. its syntactic environment. known older proposals, as well as a third important concept: The traditional cross-classification of case suffixes by declension-class and by case- name (nominative, genitive, etc.) reflects these two factors. 1. Morphology assignment: When [or a projection of ] merges with and assigns an affix, the affix is copied α α β α • Specialness of the standard case names: Traditionally, the cases are called by onto β and realized on the (accessible) lexical items dominated by β. special names (nominative, genitive, etc.) not used outside the description of case- systems. The specialness of case terminology reflects what looks like a complex This proposal revives the notion of case assignment (Vergnaud (2006); Rouveret & relation between syntactic environment and choice of case suffix. -

Roman Tombstones and the Dative Case

Roman Tombstones and the Dative Case Modern tombstones can be very simple. Sometimes they just show the name of the person who has died and how long he/she lived. The Romans did things differently. They carved both the name of the person who had died and the name of the person who paid for tombstone. Roman names and the Dative Case In Latin, the name of person who has set up the tombstone appears in the nominative. The name of the person that the tombstone is for is in the dative. The dative case in Latin means “to” or “for”. Most Roman women’s names (e.g. Octavia, Cornelia, Iulia) belong to the 1st declension. Most Roman men’s names (e.g. Marcus, Lucius, Publius) belong to the 2nd declension. 1st declension 2nd declension Nominative Octavia Marcus Accusative Octaviam Marcum Genitive Octaviae Marci Dative Octaviae Marco Ablative Octavia Marco Looking at the endings is especially important in Latin, because it’s the only way to find out who’s doing what. UnliKe in English, it doesn’t matter what order the names appear in! fecit – ‘set this up’ a) Marcus Octaviae fecit The Latin word fecit literally means ‘did it’ or ‘made it’. But b) Octaviae Marcus fecit Marcus set this up for Octavia on a Roman tombstone, it c) Marcus fecit Octaviae means that the person arranged for the stone to be made and d) Octaviae fecit Marcus displayed. 1 Exercise 1: Try translating these Roman tombstones into English. D M D M stands for Dis Manibus – ‘For the Manes gods’ but which might be better translated as ‘To the spirits of the departed’. -

Session C4: More Nouns 1. 4Th & 5Th Declension

Session C4: More Nouns 1. 4 th & 5th Declension – Chapters 20 – 22, LFCC The fourth declension endings are very similar in some ways to the third declension; they differ in that the vowel u is featured in every form. Endings Masculine & Feminine CASE sing. plural sing. plural Nominative -us -üs früctus früctüs Genitive -üs -uum früctüs früctuu m Dative -uï -ibus früctuï früctibu s Accusative -um -üs früctum früctüs Ablative -ü -ibus früctü früctibu s Nota Bene: • The masculine and feminine forms are the same. • The nominative and accusative endings are similar to third, replacing the e with a u. • The genitive plural still ends in um, as it has for every declension thus far: ärum, örum, um, uum. • The dative and ablative plural are identical to third declension. • The ablative singular ends in a single vowel, as it has for every declension. Caveat magister: Domus is a fourth declension feminine noun, but it does use the accusative plural form (domös) and the ablative singular form (domö) from the second declension. (See p. 157-158, Ch. 20, Primer C) Most nouns in the fourth declension are masculine. The few feminine and neuter exceptions that do exist, however, are quite common. Feminine Neuter domus, üs house cornü, üs wing (of an army); horn manus, üs hand; band (of men) genü, üs knee Endings Neuter CASE sing. plural sing. plural Nominative -ü -ua genü genua Genitive -üs -uum genüs genuum Dative -ü -ibus genü genibus Accusative -ü -ua genü genua Ablative -ü -ibus genü genibus Practice: 1. Declension W.S. The fifth declension is the smallest of all declensions. -

Syntax of Hungarian. Nouns and Noun Phrases, Volume 2

Comprehensive Grammar Resources Series editors: Henk van Riemsdijk, István Kenesei and Hans Broekhuis Syntax of Hungarian Nouns and Noun Phrases Volume 2 Edited by Gábor Alberti and Tibor Laczkó Syntax of Hungarian Nouns and Noun Phrases Volume II Comprehensive Grammar Resources With the rapid development of linguistic theory, the art of grammar writing has changed. Modern research on grammatical structures has tended to uncover many constructions, many in depth properties, many insights that are generally not found in the type of grammar books that are used in schools and in fields related to linguistics. The new factual and analytical body of knowledge that is being built up for many languages is, unfortunately, often buried in articles and books that concentrate on theoretical issues and are, therefore, not available in a systematized way. The Comprehensive Grammar Resources (CGR) series intends to make up for this lacuna by publishing extensive grammars that are solidly based on recent theoretical and empirical advances. They intend to present the facts as completely as possible and in a way that will “speak” to modern linguists but will also and increasingly become a new type of grammatical resource for the semi- and non- specialist. Such grammar works are, of necessity, quite voluminous. And compiling them is a huge task. Furthermore, no grammar can ever be complete. Instead new subdomains can always come under scientific scrutiny and lead to additional volumes. We therefore intend to build up these grammars incrementally, volume by volume. In view of the encyclopaedic nature of grammars, and in view of the size of the works, adequate search facilities must be provided in the form of good indices and extensive cross-referencing.