Busting Myths About the State and the Libertarian Alternative Second Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ayn Rand? Ayn Rand Ayn

Who Is Ayn Rand? Ayn Rand Few 20th century intellectuals have been as influential—and controversial— as the novelist and philosopher Ayn Rand. Her thinking still has a profound impact, particularly on those who come to it through her novels, Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead—with their core messages of individualism, self-worth, and the right to live without the impositions of others. Although ignored or scorned by some academics, traditionalists, pro- gressives, and public intellectuals, her thought remains a major influence on Ayn Rand many of the world’s leading legislators, policy advisers, economists, entre- preneurs, and investors. INTRODUCTION AN Why does Rand’s work remain so influential? Ayn Rand: An Introduction illuminates Rand’s importance, detailing her understanding of reality and human nature, and explores the ongoing fascination with and debates about her conclusions on knowledge, morality, politics, economics, government, AN INTRODUCTION public issues, aesthetics and literature. The book also places these in the context of her life and times, showing how revolutionary they were, and how they have influenced and continue to impact public policy debates. EAMONN BUTLER is director of the Adam Smith Institute, a leading think tank in the UK. He holds degrees in economics and psychology, a PhD in philosophy, and an honorary DLitt. A former winner of the Freedom Medal of Freedom’s Foundation at Valley Forge and the UK National Free Enterprise Award, Eamonn is currently secretary of the Mont Pelerin Society. Butler is the author of many books, including introductions on the pioneering economists Eamonn Butler Adam Smith, Milton Friedman, F. -

How to Win in the Game of Politics Your Own Lobby Groups, Pursue Higher Forms of Law, and Social Graces Therein

How to Win in the Game of Politics your own lobby groups, pursue higher forms of law, and social graces therein. I will however give you three ways to help the by JD Stuer Libertarian Party with constant lobbying commitments and simultaneously make participants more successful with both Unfortunately, almost money and position as a result. everything we have experienced as libertarians is a shroud over 1) Meme groups, social media groups, and party position: The our eyes. Politics is a very Libertarians actually form a glue between the Republican and tough subject with a lot of Democratic parties. We have become well-known as the emotional tension surrounding “mortar between the bricks” or “the referees” of the political issues often held dear to people. arena. These are powerful metaphors to use in social situations For this reason, the Republican to bridge the gap between the unreasonable Left and Right. and Democratic parties have Use powerful metaphors to draw power and interest from our adopted a “stick-to-it-iveness” opponent parties and/or people upset with these parties for about platform policies and letting them down, directing them towards Libertarian ideals! have functioned in the past like opposing mafia groups, 2) Find news articles about gridlock: These are easy to find but supporting only those who are arguably harder to respond to for Libertarians. The idea here is on their own side regardless of right or wrong. that gridlock isn’t all about Republicans or Democrats, but rather about Americans. Libertarians as being “the glue”, What I have noticed recently, in the polls and throughout the “mortar”, or “referees” between world, is that Republicans and Democrats, like gangs, have the two old parties holds a certain become increasingly more infatuated with winning. -

Books, Documents, Speeches & Films to Read Or

Books, Documents, Speeches & Films to Read or See Roger Ream, Fund for American Studies Email: [email protected], Website: www.tfas.org Video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0FB0EhPM_M4 American documents & speeches: Declaration of Independence The Constitution Federalist Papers The Anti-Federalist Washington’s Farewell Address Jefferson 2nd Inaugural Address Gettysburg Address Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death speech of Patrick Henry Ronald Reagan’s Time for Choosing speech (1964) Barry Goldwater’s Acceptance Speech to the 1964 Republican Convention First Principles The Law, Frederic Bastiat A Conflict of Visions, Thomas Sowell Libertarianism: A Reader, David Boaz Libertarianism: A Primer, David Boaz Liberty & Tyranny, Mark Levin Anarchy, State and Utopia, Robert Nozick The Constitution of Liberty, F.A. Hayek Conscience of a Conservative, Barry Goldwater What It Means to Be a Libertarian, Charles Murray Capitalism and Freedom, Milton Friedman Free Market Economics Economics in One Lesson, Henry Hazlitt Eat the Rich, P.J. O’Rourke Common Sense Economics: What Everyone Should Know about Wealth & Prosperity: James Gwartney, Richard Stroup and Dwight Lee Free to Choose, Milton Friedman Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith Capitalism, Socialism & Democracy, Joseph Schumpeter Basic Economics: A Citizen’s Guide to the Economy, Thomas Sowell Human Action, Ludwig von Mises Principles of Economics, Carl Menger Myths of Rich and Poor, W. Michael Cox and Richard Alm The Economic Way of Thinking, 10th edition, Paul Heyne, Peter J. Boettke, David L. Prychitko Give Me a Break: How I Exposed Hucksters, Cheats and Scam Artists and Became the Scourge of the Liberal Media…, John Stossel Other books of importance: The Road to Serfdom, F.A. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Archival Insights into the Evolution of Economics (and Related Projects) Berlet, C. (2017). Hayek, Mises, and the Iron Rule of Unintended Consequences. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek a Collaborative Biography Part IX: Te Divine Right of the ‘Free’ Market. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Farrant, A., & McPhail, E. (2017). Hayek, Tatcher, and the Muddle of the Middle. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek: A Collaborative Biography Part IX the Divine Right of the Market. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Filip, B. (2018a). Hayek on Limited Democracy, Dictatorships and the ‘Free’ Market: An Interview in Argentina, 1977. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek a Collaborative Biography Part XIII: ‘Fascism’ and Liberalism in the (Austrian) Classical Tradition. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan. Filip, B. (2018b). Hayek and Popper on Piecemeal Engineering and Ordo- Liberalism. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek a Collaborative Biography Part XIV: Orwell, Popper, Humboldt and Polanyi. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Friedman, M. F. (2017 [1991]). Say ‘No’ to Intolerance. In R. Leeson & C. Palm (Eds.), Milton Friedman on Freedom. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press. © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2019 609 R. Leeson, Hayek: A Collaborative Biography, Archival Insights into the Evolution of Economics, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78069-6 610 Bibliography Glasner, D. (2018). Hayek, Gold, Defation and Nihilism. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek a Collaborative Biography Part XIII: ‘Fascism’ and Liberalism in the (Austrian) Classical Tradition. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Goldschmidt, N., & Hesse, J.-O. (2013). Eucken, Hayek, and the Road to Serfdom. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek: A Collaborative Biography Part I Infuences, from Mises to Bartley. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

Libertarians in Bush's World

ESSAY ON LIBERTY+ LIBERTARIANS IN BUSH’S WORLD Todd Seavey* Imagine ordinary, non-ideological people hearing about an obscure politi- cal sect called libertarianism, which emphasizes self-ownership, property rights, resistance to tyranny and violence, the reduction of taxation and regulation, control over one’s own investments, and the de-emphasizing of litigation as a primary means of dispute resolution. Since this philosophy has very few adherents in the general population and is very much a minority position among intellectuals, one might expect proponents of the creed to count themselves lucky, given the likely alternatives, if the president of the country in which most of them live increasingly emphasized the themes of freedom and ownership in his major speeches; toppled brutal totalitarian regimes in two countries while hounding democracy-hating theocratic terrorists around the globe; cut taxes (despite howls even from some in the free-market camp that the cuts were too deep); called for simplification of the tax code; appointed relatively industry-friendly officials to major regulatory bodies such as the Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration despite frequent criti- cism by the media; proposed partially privatizing Social Security (America’s largest socialist boondoggle but one long regarded as sacrosanct by political analysts); and pushed tort reform to combat the chilling effect of lawsuits on doctors and manu- facturers. + Essays on Liberty is a continuing series of the Journal of Law & Liberty, dedicated to explorations of freedom and law from perspectives outside the legal academy. * Director of Publications for the American Council on Science and Health (ACSH.org, HealthFactsAnd- Fears.com), which does not necessarily endorse the views expressed here. -

Mises Research Report

CSSN Research Report 2021:2: The Mises Institute Network and Climate Policy. 9 Findings Policy Briefing July 2021 About the authors October, 2020. CSSN seeks to coordinate, conduct and support peer-reviewed research into the Dieter Plehwe is a Research Fellow at the Center for institutional and cultural dynamics of the political Civil Society Research at the Berlin Social Science conflict over climate change, and assist scholars in Center, Germany. Max Goldenbaum is a Student outreach to policymakers and the public. Assistant of the Center for Civil Society Research at the Berlin Social Science Center, Germany. Archana This report should be cited as: Ramanujam is a Graduate student in Sociology at Brown University, USA .Ruth McKie is a Senior Plehwe, Dieter, Max Goldenbaum, Archana Lecturer in Criminology at De Montfort University, Ramanujam, Ruth McKie, Jose Moreno, Kristoffer UK. Jose Moreno is a Predoctoral Fellow at Pompeu Ekberg, Galen Hall, Lucas Araldi, Jeremy Walker, Fabra University, Spain. Kristoffer Ekberg is a Robert Brulle, Moritz Neujeffski, Nick Graham, and Postdoctoral Historian at Chalmers University, Milan Hrubes. 2021. “The Mises Network and Sweden, Galen Hall is a recent graduate of Brown Climate Policy.” Policy Briefing, The Climate Social University and researcher in the Climate and Science Network. July 2021. Development Lab at Brown University, USA, Lucas https://www.cssn.org/ Araldi is a PhD student in Political Science at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Jeremy Walker is a researcher with the Climate Justice Research Centre at the University of Technology Sydney. Robert Brulle, Visiting Professor of Climate Social Science Network Environment and Society and Director of Research, Climate Social Science Network, Brown University. -

(Pdf) Download

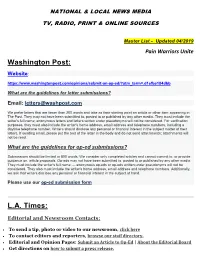

NATIONAL & LOCAL NEWS MEDIA TV, RADIO, PRINT & ONLINE SOURCES Master List - Updated 04/2019 Pain Warriors Unite Washington Post: Website: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/submit-an-op-ed/?utm_term=.d1efbe184dbb What are the guidelines for letter submissions? Email: [email protected] We prefer letters that are fewer than 200 words and take as their starting point an article or other item appearing in The Post. They may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name; anonymous letters and letters written under pseudonyms will not be considered. For verification purposes, they must also include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers, including a daytime telephone number. Writers should disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject matter of their letters. If sending email, please put the text of the letter in the body and do not send attachments; attachments will not be read. What are the guidelines for op-ed submissions? Submissions should be limited to 800 words. We consider only completed articles and cannot commit to, or provide guidance on, article proposals. Op-eds may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name — anonymous op-eds or op-eds written under pseudonyms will not be considered. They also must include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers. Additionally, we ask that writers disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject at hand. Please use our op-ed submission form L.A. -

Towards Libertarian Welfarism: Protecting Agency in the Night- Watchman State Marius S

This article was downloaded by: [the Bodleian Libraries of the University of Oxford] On: 06 February 2013, At: 03:21 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Political Ideologies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjpi20 Towards libertarian welfarism: protecting agency in the night- watchman state Marius S. Ostrowski a a Magdalen College, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX1 4AU, UK Version of record first published: 25 Jan 2013. To cite this article: Marius S. Ostrowski (2013): Towards libertarian welfarism: protecting agency in the night-watchman state, Journal of Political Ideologies, 18:1, 107-128 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2013.750182 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Department of Economics, City University London

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Denis, A. (2010). A century of methodological individualism part 2: Mises and Hayek (10/03). London, UK: Department of Economics, City University London. This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1489/ Link to published version: 10/03 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Department of Economics A Century of Methodological Individualism Part 2: Mises and Hayek Andy Denis1 City University London Department of Economics Discussion Paper Series No. 10/03 1 Department of Economics, City University London, Social Sciences Bldg, Northampton Square, London EC1V 0HB, UK. Email: [email protected]. T: +44 (0)20 7040 0257 A Century of Methodological Individualism Part 2: Mises and Hayek Andy Denis City University London [email protected] Version 1: January 2010 2009 marks the centenary of methodological individualism (MI). -

A Response to the Libertarian Critics of Open-Borders Libertarianism

LINCOLN MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW __________________________________ VOLUME 4 FALL 2016 ISSUE 1 ____________________________________ A RESPONSE TO THE LIBERTARIAN CRITICS OF OPEN-BORDERS LIBERTARIANISM Walter E. Block, Ph.D. Harold E. Wirth Eminent Scholar Endowed Chair and Professor of Economics Joseph A. Butt, S.J. College of Business I. INTRODUCTION Libertarians may be unique in many regards, but their views on immigration do not qualify. They are as divided as is the rest of the population on this issue. Some favor open borders, and others oppose such a legal milieu. The present paper may be placed in the former category. It will outline both sides of this debate in sections II and III. Section IV is devoted to some additional arrows in the quiver of the closed border libertarians, and to a refutation of them. We conclude in section V. A RESPONSE TO THE LIBERTARIAN CRITICS OF OPEN-BORDERS LIBERTARIANISM 143 II. ANTI OPEN BORDERS The libertarian opposition to free immigration is straightforward and even elegant.1 It notes, first, a curious bifurcation in international economic relations. In the case of both trade and investment, there must necessarily be two2 parties who agree to the commercial interaction. In the former case, there must be an importer and an exporter; both are necessary. Without the consent of both parties, the transaction cannot take place. A similar situation arises concerning foreign investment. The entrepreneur who wishes to set up shop abroad must obtain the willing acquiescence of the domestic partner for the purchase of land and raw materials. And the same occurs with financial transactions that take place across 1 Peter Brimelow, ALIEN NATION: COMMON SENSE ABOUT AMERICA’S IMMIGRATION DISASTER (1995); Jesús Huerta De Soto, A Libertarian Theory of Free Immigration, 13 J.