Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bon Echo Provincial Park

BON ECHO PROVINCIAL PARK One Malaise trap was deployed at Bon Echo Provincial Park in 2014 (44.89405, -77.19691 278m ASL; Figure 1). This trap collected arthropods for twenty weeks from May 7 – September 24, 2014. All 10 Malaise trap samples were processed; every other sample was analyzed using the individual specimen protocol while the second half was analyzed via bulk analysis. A total of 2559 BINs were obtained. Over half the BINs captured were flies (Diptera), followed by bees, ants and wasps (Hymenoptera), moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera), and beetles (Coleoptera; Figure 2). In total, 547 arthropod species were named, representing 22.9% of the BINs from the site (Appendix 1). All BINs were assigned at least to Figure 1. Malaise trap deployed at Bon Echo family, and 57.2% were assigned to a genus (Appendix Provincial Park in 2014. 2). Specimens collected from Bon Echo represent 223 different families and 651 genera. Diptera Hymenoptera Lepidoptera Coleoptera Hemiptera Mesostigmata Trombidiformes Psocodea Sarcoptiformes Trichoptera Araneae Entomobryomorpha Symphypleona Thysanoptera Neuroptera Opiliones Mecoptera Orthoptera Plecoptera Julida Odonata Stylommatophora Figure 2. Taxonomy breakdown of BINs captured in the Malaise trap at Bon Echo. APPENDIX 1. TAXONOMY REPORT Class Order Family Genus Species Arachnida Araneae Clubionidae Clubiona Clubiona obesa Linyphiidae Ceraticelus Ceraticelus atriceps Neriene Neriene radiata Philodromidae Philodromus Salticidae Pelegrina Pelegrina proterva Tetragnathidae Tetragnatha Tetragnatha shoshone -

Topic Paper Chilterns Beechwoods

. O O o . 0 O . 0 . O Shoping growth in Docorum Appendices for Topic Paper for the Chilterns Beechwoods SAC A summary/overview of available evidence BOROUGH Dacorum Local Plan (2020-2038) Emerging Strategy for Growth COUNCIL November 2020 Appendices Natural England reports 5 Chilterns Beechwoods Special Area of Conservation 6 Appendix 1: Citation for Chilterns Beechwoods Special Area of Conservation (SAC) 7 Appendix 2: Chilterns Beechwoods SAC Features Matrix 9 Appendix 3: European Site Conservation Objectives for Chilterns Beechwoods Special Area of Conservation Site Code: UK0012724 11 Appendix 4: Site Improvement Plan for Chilterns Beechwoods SAC, 2015 13 Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI 27 Appendix 5: Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI citation 28 Appendix 6: Condition summary from Natural England’s website for Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI 31 Appendix 7: Condition Assessment from Natural England’s website for Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI 33 Appendix 8: Operations likely to damage the special interest features at Ashridge Commons and Woods, SSSI, Hertfordshire/Buckinghamshire 38 Appendix 9: Views About Management: A statement of English Nature’s views about the management of Ashridge Commons and Woods Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), 2003 40 Tring Woodlands SSSI 44 Appendix 10: Tring Woodlands SSSI citation 45 Appendix 11: Condition summary from Natural England’s website for Tring Woodlands SSSI 48 Appendix 12: Condition Assessment from Natural England’s website for Tring Woodlands SSSI 51 Appendix 13: Operations likely to damage the special interest features at Tring Woodlands SSSI 53 Appendix 14: Views About Management: A statement of English Nature’s views about the management of Tring Woodlands Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), 2003. -

SYSTEMATICS of the MEGADIVERSE SUPERFAMILY GELECHIOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTEA) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of T

SYSTEMATICS OF THE MEGADIVERSE SUPERFAMILY GELECHIOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTEA) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sibyl Rae Bucheli, M.S. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. John W. Wenzel, Advisor Dr. Daniel Herms Dr. Hans Klompen _________________________________ Dr. Steven C. Passoa Advisor Graduate Program in Entomology ABSTRACT The phylogenetics, systematics, taxonomy, and biology of Gelechioidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) are investigated. This superfamily is probably the second largest in all of Lepidoptera, and it remains one of the least well known. Taxonomy of Gelechioidea has been unstable historically, and definitions vary at the family and subfamily levels. In Chapters Two and Three, I review the taxonomy of Gelechioidea and characters that have been important, with attention to what characters or terms were used by different authors. I revise the coding of characters that are already in the literature, and provide new data as well. Chapter Four provides the first phylogenetic analysis of Gelechioidea to include molecular data. I combine novel DNA sequence data from Cytochrome oxidase I and II with morphological matrices for exemplar species. The results challenge current concepts of Gelechioidea, suggesting that traditional morphological characters that have united taxa may not be homologous structures and are in need of further investigation. Resolution of this problem will require more detailed analysis and more thorough characterization of certain lineages. To begin this task, I conduct in Chapter Five an in- depth study of morphological evolution, host-plant selection, and geographical distribution of a medium-sized genus Depressaria Haworth (Depressariinae), larvae of ii which generally feed on plants in the families Asteraceae and Apiaceae. -

Entomology of the Aucklands and Other Islands South of New Zealand: Lepidoptera, Ex Cluding Non-Crambine Pyralidae

Pacific Insects Monograph 27: 55-172 10 November 1971 ENTOMOLOGY OF THE AUCKLANDS AND OTHER ISLANDS SOUTH OF NEW ZEALAND: LEPIDOPTERA, EX CLUDING NON-CRAMBINE PYRALIDAE By J. S. Dugdale1 CONTENTS Introduction 55 Acknowledgements 58 Faunal Composition and Relationships 58 Faunal List 59 Key to Families 68 1. Arctiidae 71 2. Carposinidae 73 Coleophoridae 76 Cosmopterygidae 77 3. Crambinae (pt Pyralidae) 77 4. Elachistidae 79 5. Geometridae 89 Hyponomeutidae 115 6. Nepticulidae 115 7. Noctuidae 117 8. Oecophoridae 131 9. Psychidae 137 10. Pterophoridae 145 11. Tineidae... 148 12. Tortricidae 156 References 169 Note 172 Abstract: This paper deals with all Lepidoptera, excluding the non-crambine Pyralidae, of Auckland, Campbell, Antipodes and Snares Is. The native resident fauna of these islands consists of 42 species of which 21 (50%) are endemic, in 27 genera, of which 3 (11%) are endemic, in 12 families. The endemic fauna is characterised by brachyptery (66%), body size under 10 mm (72%) and concealed, or strictly ground- dwelling larval life. All species can be related to mainland forms; there is a distinctive pre-Pleistocene element as well as some instances of possible Pleistocene introductions, as suggested by the presence of pairs of species, one member of which is endemic but fully winged. A graph and tables are given showing the composition of the fauna, its distribution, habits, and presumed derivations. Host plants or host niches are discussed. An additional 7 species are considered to be non-resident waifs. The taxonomic part includes keys to families (applicable only to the subantarctic fauna), and to genera and species. -

P. Josephinae, A. Micella, H. Rhomboidella

2010, Entomologist’s Gazette 61: 207–221 Notes on the early stages of four species of Oecophoridae, Gelechiidae and Pyralidae (Lepidoptera) in the British Isles R. J. HECKFORD 67 Newnham Road, Plympton, Plymouth, Devon PL7 4AW,U.K. Synopsis Descriptions are given of the early stages of Pseudatemelia josephinae (Toll, 1956), Argolamprotes micella ([Denis & Schiffermüller], 1775), Hypatima rhomboidella (Linnaeus, 1758) and Pyrausta cingulata (Linnaeus, 1758). Key words: Lepidoptera, Oecophoridae, Gelechiidae, Pyralidae, Pseudatemelia josephinae, Argolamprotes micella, Hypatima rhomboidella, Pyrausta cingulata, ovum, larva. Pseudatemelia josephinae (Toll, 1956) (Oecophoridae) It appears that the only descriptions of the ovum, larva and life-cycle in the British literature are those given by Langmaid (2002a: 103–104) and these are stated to be based on those by Heylaerts (1884: 150). Heylaerts’ paper begins by referring to an account of the larva given by Fologne (1860: 102–103), under the name Oecophora flavifrontella ([Denis & Schiffermüller], 1775), now Pseudatemelia flavifrontella. Heylaerts also uses the name Oecophora flavifrontella but Langmaid follows Jäckh (1959: 174–184) in attributing Heylaerts’ description to Pseudatemelia josephinae, then an undescribed species. Although neither Fologne nor Heylaerts gives any indication of localities, because they published their accounts in a Belgian periodical I presume that both found the species in that country. After P. josephinae was described in 1956 it was found to occur in Belgium. Fologne (1860: 102–103) states that he found cases in May on the trunks of ‘hêtres’, beech trees (Fagus sylvatica L.), onto which he assumed they had climbed towards evening to eat and that during the day they remain concealed amongst dry leaves. -

New Records of Microlepidoptera in Alberta, Canada

Volume 59 2005 Number 2 Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 59(2), 2005, 61-82 NEW RECORDS OF MICROLEPIDOPTERA IN ALBERTA, CANADA GREGORY R. POHL Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Northern Forestry Centre, 5320 - 122 St., Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6H 3S5 email: [email protected] CHARLES D. BIRD Box 22, Erskine, Alberta, Canada T0C 1G0 email: [email protected] JEAN-FRANÇOIS LANDRY Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada, 960 Carling Ave, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A 0C6 email: [email protected] AND GARY G. ANWEILER E.H. Strickland Entomology Museum, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, T6G 2H1 email: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Fifty-seven species of microlepidoptera are reported as new for the Province of Alberta, based primarily on speci- mens in the Northern Forestry Research Collection of the Canadian Forest Service, the University of Alberta Strickland Museum, the Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids, and Nematodes, and the personal collections of the first two authors. These new records are in the families Eriocraniidae, Prodoxidae, Tineidae, Psychidae, Gracillariidae, Ypsolophidae, Plutellidae, Acrolepi- idae, Glyphipterigidae, Elachistidae, Glyphidoceridae, Coleophoridae, Gelechiidae, Xyloryctidae, Sesiidae, Tortricidae, Schrecken- steiniidae, Epermeniidae, Pyralidae, and Crambidae. These records represent the first published report of the families Eriocrani- idae and Glyphidoceridae in Alberta, of Acrolepiidae in western Canada, and of Schreckensteiniidae in Canada. Tetragma gei, Tegeticula -

Clothes Moths ENTFACT-609 by Michael F

Clothes Moths ENTFACT-609 By Michael F. Potter, Extension Entomologist, University of Kentucky Clothes moths are pests that can destroy fabric and other materials. They feed exclusively on animal fibers, especially wool, fur, silk, feathers, felt, and leather. These materials contain keratin, a fibrous protein that the worm-like larvae of the clothes moth can digest. (In nature, the larvae feed on the nesting materials or carcasses of birds and mam- mals.) Cotton and synthetic fabrics such as poly- ester and rayon are rarely attacked unless blended with wool, or heavily soiled with food stains or body oils. Serious infestations of clothes moths Fig. 1b: Indianmeal moth can develop undetected in dwellings, causing ir- Two different types of clothes moths are common reparable harm to vulnerable materials. in North America — the webbing clothes moth Facts about Clothes Moths (Tineola bisselliella) and the casemaking clothes moth (Tinea pellionella). Adult webbing clothes Clothes moths are small, 1/2-inch moths that are moths are a uniform, buff-color, with a small tuft beige or buff-colored. They have narrow wings of reddish hairs on top of the head. Casemaking that are fringed with small hairs. They are often clothes moths are similar in appearance, but have mistaken for grain moths infesting stored food dark specks on the wings. Clothes moth adults do items in kitchens and pantries. Unlike some other not feed so they cause no injury to fabrics. How- types of moths, clothes moths are seldom seen be- ever, the adults lay about 40-50 pinhead-sized cause they avoid light. -

Contribution to the Lepidoptera Fauna of the Madeira Islands Part 2

Beitr. Ent. Keltern ISSN 0005 - 805X 51 (2001) 1 S. 161 - 213 14.09.2001 Contribution to the Lepidoptera fauna of the Madeira Islands Part 2. Tineidae, Acrolepiidae, Epermeniidae With 127 figures Reinhard Gaedike and Ole Karsholt Summary A review of three families Tineidae, Epermeniidae and Acrolepiidae in the Madeira Islands is given. Three new species: Monopis henderickxi sp. n. (Tineidae), Acrolepiopsis mauli sp. n. and A. infundibulosa sp. n. (Acrolepiidae) are described, and two new combinations in the Tineidae: Ceratobia oxymora (MEYRICK) comb. n. and Monopis barbarosi (KOÇAK) comb. n. are listed. Trichophaga robinsoni nom. n. is proposed as a replacement name for the preoccupied T. abrkptella (WOLLASTON, 1858). The first record from Madeira of the family Acrolepiidae (with Acrolepiopsis vesperella (ZELLER) and the two above mentioned new species) is presented, and three species of Tineidae: Stenoptinea yaneimarmorella (MILLIÈRE), Ceratobia oxymora (MEY RICK) and Trichophaga tapetgella (LINNAEUS) are reported as new to the fauna of Madeira. The Madeiran records given for Tsychoidesfilicivora (MEYRICK) are the first records of this species outside the British Isles. Tineapellionella LINNAEUS, Monopis laevigella (DENIS & SCHIFFERMULLER) and M. imella (HÜBNER) are dele ted from the list of Lepidoptera found in Madeira. All species and their genitalia are figured, and informa tion on bionomy is presented. Zusammenfassung Es wird eine Übersicht über die drei Familien Tineidae, Epermeniidae und Acrolepiidae auf den Madeira Inseln gegeben. Die drei neuen Arten Monopis henderickxi sp. n. (Tineidae), Acrolepiopsis mauli sp. n. und A. infundibulosa sp. n. (Acrolepiidae) werden beschrieben, zwei neue Kombinationen bei den Tineidae: Cerato bia oxymora (MEYRICK) comb. -

Lepidoptera: Tineidae

Beitr. Ent. Keltern ISSN 0005 - 805X 56 (2006) 1 S. 213-229 15.08.2006 Some new or poorly known tineids from Central Asia, the Russian Far East and China (Lepidoptera: T in e id a e ) With 18 figures R e in h a r d G a e d ik e Summary Results are presented of the examination of tineid material from the Finnish Museum of Natural History, Helsinki (FMNH) and the Institute of Animal Systematics and Ecology, Siberian Zoological Museum Novosibirsk (SZMN). As new species are described Tinea albomaculata from China, Tinea fiiscocostalis from Russia, Tinea kasachica from Kazachstan, and Monopis luteocostalis from Russia. The previously unknown male of Tinea semifulvelloides is described. New records for several countries for 15 species are established. Zusammenfassung Es werden die Ergebnisse der Untersuchung von Tineidenmaterial aus dem Finnish Museum of Natural History, Helsinki (FMNH), und aus dem Institute of Animal Systematics and Ecology, Siberian Zoological Museum Novosibirsk (SZMN) vorgelegt. Als neu werden beschrieben Tinea albom aculata aus China, Tinea fuscocostalis aus Russland, Tinea kasachica aus Kasachstan und Monopis luteocostalis aus Russland. Von Tinea semifitlvelloides war es möglich, das bisher unbekannte Männchen zu beschreiben. Neufunde für verschiede ne Länder wurden für 15 Arten festgestellt. Keywords Tineidae, faunistics, taxonomy, four new species, new records, Palaearctic region. My collègue L a u r i K a il a from the Finnish Museum of Natural History, Helsinki (FMNH) was so kind as to send me undetermined Tineidae, collected by several Finnish entomologists during recent years in various parts of Russia (Siberia, Buryatia, Far East), in Central Asia, and China. -

Lepidoptera: Tineidae) from Chinazoj 704 1..14

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2011, 163, 1–14. With 5 figures A revision of the Monopis monachella species complex (Lepidoptera: Tineidae) from Chinazoj_704 1..14 GUO-HUA HUANG1*, LIU-SHENG CHEN2, TOSHIYA HIROWATARI3, YOSHITSUGU NASU4 and MING WANG5 1Institute of Entomology, College of Bio-safety Science and Technology, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha 410128, Hunan Province, China. E-mail: [email protected] 2College of Agriculture, Shihezi University, Shihezi 832800, Xinjiang, China. E-mail: [email protected] 3Entomological Laboratory, Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Osaka Prefecture University, Sakai 599-8531, Osaka, Japan. E-mail: [email protected] 4Osaka Plant Protection Office: Habikino, Osaka 583-0862, Japan. E-mail: [email protected] 5Department of Entomology, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510640, Guangdong Province, China. E-mail: [email protected] Received 19 March 2010; revised 21 September 2010; accepted for publication 24 September 2010 The Monopis monachella species complex from China is revised, and its relationship to other species complexes of the genus Monopis is discussed with reference to morphological, and molecular evidence. Principal component analysis on all available specimens provided supporting evidence for the existence of three species, one of which is described as new: Monopis iunctio Huang & Hirowatari sp. nov. All species are either diagnosed or described, and illustrated, and information is given on their distribution and host range. Additional information is given on the biology and larval stages of Monopis longella. A preliminary phylogenetic study based on mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene (CO1) sequence data and a key to the species of the M. -

Webbing Clothes Moth

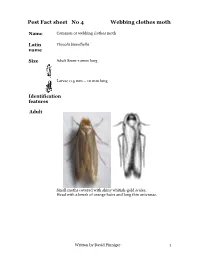

Pest Fact sheet No 4 Webbing clothes moth Name Common or webbing clothes moth Latin Tineola bisselliella name Size Adult 8mm-10mm long Larvae 0.5 mm – 10 mm long Identification features Adult Small moths covered with shiny whitish-gold scales. Head with a brush of orange hairs and long thin antennae. Written by David Pinniger 1 Larva White with an orange-brown head capsule. Often hidden by tubes of silk webbing. Written by David Pinniger 2 Life cycle Adult moths fly well when it is warm and females lay batches of eggs on wool, fur, feathers and other organic materials. When the larvae first hatch they are extremely small, less than 0.5 mm, and they remain in the material where they have hatched. As they feed and grow, they secrete silk webbing which sticks to the material they are living on. As they get larger, the silk forms tubes around them. They prefer dark undisturbed places and are rarely seen unless disturbed. In unheated buildings, the larvae may take nearly a year to complete their growth and each new cycle starts after they pupate and change into adults in the Spring. In heated buildings they may complete two complete cycles per year with another emergence of adult moths in the Autumn. In very warm buildings there may even be three generations per year with moths appearing at any time. Signs of damage Irregular holes, silk webbing and gritty pellets of excreta, called frass, are signs of moth attack. Silk webbing on wool carpet Written by David Pinniger 3 Silk webbing stuck to canvas fabric Materials The larvae are voracious feeders and will graze on and make damaged holes in woollen textiles, animal specimens, fur and feathers. -

Natural History of Lepidoptera Associated with Bird Nests in Mid-Wales

Entomologist’s Rec. J. Var. 130 (2018) 249 NATURAL HISTORY OF LEPIDOPTERA ASSOCIATED WITH BIRD NESTS IN MID-WALES D. H. B OYES Bridge Cottage, Middletown, Welshpool, Powys, SY21 8DG. (E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract Bird nests can support diverse communities of invertebrates, including moths (Lepidoptera). However, the understanding of the natural history of these species is incomplete. For this study, 224 nests, from 16 bird species, were collected and the adult moths that emerged were recorded. The majority of nests contained moths, with 4,657 individuals of ten species recorded. Observations are made on the natural history of each species and some novel findings are reported. The absence of certain species is discussed. To gain deeper insights into the life histories of these species, it would be useful to document the feeding habits of the larvae in isolation. Keywords : Commensal, detritivore, fleas, moths, Tineidae. Introduction Bird nests represent concentrated pockets of organic resources (including dead plant matter, feathers, faeces and other detritus) and can support a diverse invertebrate fauna. A global checklist compiled by Hicks (1959; 1962; 1971) lists eighteen insect orders associated with bird nests, and a study in England identified over 120 insect species, spanning eight orders (Woodroffe, 1953). Moths are particularly frequent occupants of bird nests, but large gaps in knowledge and some misapprehensions remain. For example, Tineola bisselliella (Hummel, 1823) was widely thought to infest human habitations via bird nests, which acted as natural population reservoirs. However, it has recently been discovered that this non-native species seldom occurs in rural bird nests and can be regarded as wholly synanthropic in Europe, where it was introduced from Africa around the turn of the 19th century (Plarre & Krüger- Carstensen, 2011; Plarre, 2014).