Eurovision: Performing State Identity and Shared Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Mizrahi Artists Said ‘No’ to Israel’S Pioneer Culture

Riches To Rags To Virtual Riches: When Mizrahi Artists Said ‘No’ To Israel’s Pioneer Culture Shoshana Gabay. Ills. Joseph Sassoon Semah Upon their arrival in Israel, Mizrahi Jews found themselves under a regime that demanded obedience, even in cultural matters. All were required to conform to an idealized pioneer figure who sang classical, militaristic ‘Hebrew’ songs. That is, before the ‘Kasetot’ era propelled Mizrahi artists into the spotlight, paving the way for today’s musical stars. Part two of a musical journey beginning in Israel’s Mizrahi neighborhoods of the 1950s and leading up to Palestinian singer Mohammed Assaf. Read part one here. Our early encounter with Zionist music takes place in kindergarten, then later in schools and the youth movements, usually with an accordionist in tow playing songs worn and weathered by the dry desert winds. Music teachers at school never bothered with classical music, neither Western nor Arabian, and traditional Ashkenazi liturgies – let alone Sephardic – were not even taken into account. The early pioneer music was hard to stomach, and not only because it didn’t belong to our generation and wasn’t part of our heritage. More specifically, we were gagging on something shoved obsessively down our throat by political authority. Our “founding fathers” and their children never spared us any candid detail regarding the bodily reaction they experience when hearing the music brought here by our fathers, and the music we created here. But not much was said regarding the thoughts and feelings of Mizrahi immigrants (nor about their children who were born into it) who came here and heard what passed as Israeli music, nor about their children who were born into it. -

Why Stockton Folk Dance Camp Still Produces a Syllabus

Syllabus of Dance Descriptions STOCKTON FOLK DANCE CAMP – 2018 FINAL In Memoriam Rickey Holden – 1926-2017 Rickey was a square and folk dance teacher, researcher, caller, record producer, and author. Rickey was largely responsible for spreading recreational international folk dancing throughout Europe and Asia. Rickey learned ballroom dance in Austin Texas in 1935 and 1936. He started square and contra dancing in Vermont in 1939. He taught international folk dance all over Europe and Asia, eventually making his home base in Brussels. He worked with Folkraft Records in the early years. He taught at Stockton Folk Dance Camp in the 1940s and 50s, plus an additional appearance in 1992. In addition to dozens of books about square dancing, he also authored books on Israeli, Turkish, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Greek, and Macedonian dance. STOCKTON FOLK DANCE CAMP – 2018 FINAL Preface Many of the dance descriptions in the syllabus have been or are being copyrighted. They should not be reproduced in any form without permission. Specific permission of the instructors involved must be secured. Camp is satisfied if a suitable by-line such as “Learned at Folk Dance Camp, University of the Pacific” is included. Loui Tucker served as editor of this syllabus, with valuable assistance from Karen Bennett and Joyce Lissant Uggla. We are indebted to members of the Dance Research Committee of the Folk Dance Federation of California (North and South) for assistance in preparing the Final Syllabus. Cover art copyright © 2018 Susan Gregory. (Thanks, Susan.) Please -

Riga – Tallinn

Experience Matters. Estonia – Latvia – Lithuania. CLASSICAL BALTICS 2021 - Guaranteed Departure Tours Vilnius (LITHUANIA) – Riga (LATVIA) – Tallinn (ESTONIA) – A tour that offers you a wonderful chance to visit all three BALTIC STATES - Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. 8-dayRiga guided – coach Tallinn tour, starting on Saturday in Vilnius and ending on the following Saturday in Tallinn. Click to add Text Our Services Con-ex is a leading wholesale inbound tour operator and a destination management company in the Baltic region. It is part of Latvia Tours Group. We provide high quality services from our office in Riga. Well-establishes network offices in the region permits us to offer our clients smooth execution of a variety of tour programs, wide range of high quality services combined with the best rates and conditions. More than 25 years of experience and an enthusiastic team makes Con-ex your best choice of a partner for leisure and business travel in the Baltic region and beyond. Leisure FIT and group arrangements; whether wishing to explore the beauty of the Baltic States, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia and take an extension tour to Scandinavia, Russia and other CIS countries, indulge in luxury spas, take up the challenge at the golf courses or fulfil a special wish – Con-ex meets your requests. Incentives and special events Looking for special team building activities or wanting to reward loyal clients? Gala banquet on the opera stage, bobsleigh thrill or city introduction rally – Con-ex creates the perfect experience for your company. Congresses and conferences 50 or 5000 participants – whatever the number – we organise your next meeting, seminar, conference or congress. -

Israel Resource Cards (Digital Use)

WESTERN WALL ַה ּכֹו ֶתל ַה ַּמ ַעָר ִבי The Western Wall, known as the Kotel, is revered as the holiest site for the Jewish people. A part of the outer retaining wall of the Second Temple that was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE, it is the place closest to the ancient Holy of Holies, where only the Kohanim— —Jewish priests were allowed access. When Israel gained independence in 1948, Jordan controlled the Western Wall and all of the Old City of Jerusalem; the city was reunified in the 1967 Six-Day War. The Western Wall is considered an Orthodox synagogue by Israeli authorities, with separate prayer spaces for men and women. A mixed egalitarian prayer area operates along a nearby section of the Temple’s retaining wall, raising to the forefront contemporary ideas of religious expression—a prime example of how Israel navigates between past and present. SITES AND INSIGHTS theicenter.org SHUK ׁשוּק Every Israeli city has an open-air market, or shuk, where vendors sell everything from fresh fruits and vegetables to clothing, appliances, and souvenirs. There’s no other place that feels more authentically Israeli than a shuk on Friday afternoon, as seemingly everyone shops for Shabbat. Drawn by the freshness and variety of produce, Israelis and tourists alike flock to the shuk, turning it into a microcosm of the country. Shuks in smaller cities and towns operate just one day per week, while larger markets often play a key role in the city’s cultural life. At night, after the vendors go home, Machaneh Yehuda— —Jerusalem’s shuk, turns into the city’s nightlife hub. -

July 23, 2021 the Musicrow Weekly Friday, July 23, 2021

July 23, 2021 The MusicRow Weekly Friday, July 23, 2021 Taylor Swift’s Fearless (Taylor’s Version) SIGN UP HERE (FREE!) Will Not Be Submitted For Grammy, CMA Award Consideration If you were forwarded this newsletter and would like to receive it, sign up here. THIS WEEK’S HEADLINES Fearless (Taylor’s Version) Will Not Be Submitted For Grammy, CMA Awards NSAI Sets Nashville Songwriter Awards For September Big Loud Records Ups 5, Adds 2 To Promotion Team Dylan Schneider Signs With BBR Music Group Taylor Swift will not be submitting Fearless (Taylor’s Version), the re- recorded version of her 2008 studio album that released earlier this year, Dan + Shay Have Good for Grammy or CMA Awards consideration. Things In Store For August “After careful consideration, Taylor Swift will not be submitting Fearless (Taylor’s Version) in any category at this year’s upcoming Grammy and Scotty McCreery Shares CMA Awards,” says a statement provided to MusicRow from a Republic Details Of New Album Records spokesperson. “Fearless has already won four Grammys including album of the year, as well as the CMA Award for album of the Chris DeStefano Renews year in 2009/2010 and remains the most awarded country album of all With Sony Music Publishing time.” Natalie Hemby Announces The statement goes on to share that Swift’s ninth studio album, Evermore, New Album released in December of 2020, will be submitted to the Grammys for consideration in all eligible categories. Niko Moon’s Good Time Slated For August Release Evermore arrived only five months after the surprise release of Folklore, Swift’s groundbreaking eighth studio album. -

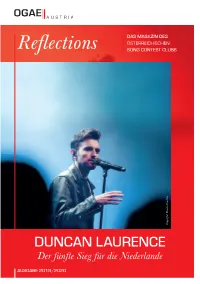

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

Cv KAULAKANE 02:05

WORK EXPERIENCE STATISTICAL ASSISTANT Eurostat, Migration and Population Apr - May 2019 EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Luxembourg City (Luxembourg) - Learning whilst working: created narrative driven reports, bridging statistical jargon with user-friendly language ! - Proofreading member state metadata MARTA KAULAKANE LIAISON TRAINEE IN HUMAN RESOURCES DEPARTMENT Mar 2019 CONTACT EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Luxembourg City (Luxembourg) - Organisational, information, documentation and logistical +371 29863439 [email protected] tasks 2210 Luxembourg City - Planned and coordinated cultural events, trips and other activities LANGUAGES - Coaching trainees to foster integration into the new working LATVIAN native environment ENGLISH C2 SPANISH C2 TRANSLATOR in the Directorate-General for Translation Oct - Feb GERMAN B1 2018-2019 RUSSIAN B1 EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Luxembourg City (Luxembourg) FRENCH A2 - Translation of EC texts, technical translations (EN-LV) PROFILE - PRESIDENT of the Trainees' Committee and Trips Subcommittee: organisation, planning and management of Appreciate culturally and linguistically diverse interinstitutional visits, cultural events and trips; communication, environments. Studied and team-building worked in 8 countries. RESEARCH INTERN Jan - Aug Diligent and versatile. 2018 Holding an unconventional Centre for Public Policy PROVIDUS, Riga (Latvia) view on things. Sense of - Seminar planning and management related to migration, empathy, drive for planning integration, civic participation and organisation. - Preparation of EU-level -

L'italia E L'eurovision Song Contest Un Rinnovato

La musica unisce l'Europa… e non solo C'è chi la definisce "La Champions League" della musica e in fondo non sbaglia. L'Eurovision è una grande festa, ma soprattutto è un concorso in cui i Paesi d'Europa si sfidano a colpi di note. Tecnicamente, è un concorso fra televisioni, visto che ad organizzarlo è l'EBU (European Broadcasting Union), l'ente che riunisce le tv pubbliche d'Europa e del bacino del Mediterraneo. Noi italiani l'abbiamo a lungo chiamato Eurofestival, i francesi sciovinisti lo chiamano Concours Eurovision de la Chanson, l'abbreviazione per tutti è Eurovision. Oggi più che mai una rassegna globale, che vede protagonisti nel 2016 43 paesi: 42 aderenti all'ente organizzatore più l'Australia, che dell'EBU è solo membro associato, essendo fuori dall'area (l’anno scorso fu invitata dall’EBU per festeggiare i 60 anni del concorso per via dei grandi ascolti che la rassegna fa in quel paese e che quest’anno è stata nuovamente invitata dall’organizzazione). L'ideatore della rassegna fu un italiano: Sergio Pugliese, nel 1956 direttore della RAI, che ispirandosi a Sanremo volle creare una rassegna musicale europea. La propose a Marcel Bezençon, il franco-svizzero allora direttore generale del neonato consorzio eurovisione, che mise il sigillo sull'idea: ecco così nascere un concorso di musica con lo scopo nobile di promuovere la collaborazione e l'amicizia tra i popoli europei, la ricostituzione di un continente dilaniato dalla guerra attraverso lo spettacolo e la tv. E oltre a questo, molto più prosaicamente, anche sperimentare una diretta in simultanea in più Paesi e promuovere il mezzo televisivo nel vecchio continente. -

¿La Hora De La Diplomacia?

Año 63 | # 974 | Diciembre 2013/Enero 2014 | $ 10,00.- ATENTADO A LA AMIA: 232 MESES SIN JUSTICIA Periodismo judeoargentino con compromiso Fundado en 1948 Relaciones Occidente-Irán- Medio Oriente ¿La hora de la Diplomacia? Escriben: Ricardo Aronskind, Damián Svalb y Carlos Escudé 30 años de democracia en Argentina “Entre esperanzas, explosiones, festejos y dilemas” por Guillermo Levy | Pag. 10 Entrevista a Luis Tonelli, director de la carrera de Ciencia Política de la UBA Pag. 9 “El día en que Hashomer Hatzair copó la plaza” , por Jonatan Lipsky | Pag. 14 “En Israel: muchos Madibas, ningún Mandela” , por Rodrigo “Afro” Remenik | Pag. 20 Diciembre 2013 - Enero 2014 Periodismo judeoargentino con compromiso | Staff-Humor 2 NUEVA SION #974 Sumario Chau 2013, otro año STAFF/HUMOR 2 EDITORIAL 3 que pasó y no volverá MEDIO ORIENTE 4 | 6 ARGENTINA 7 | 11 Por Por Roberto Moldavsky ISRAEL 12 | 13 relato contra la grieta, Lilita contra Moreno, Ventura contra Lanata y para terminar de hundir - COMUNITARIAS 14 | 16 Sacando los comerciantes del Once y Flores, todo nos la inconcebible separación de Wanda Nara y CULTURA 16 | 19 el resto de los humanos intentamos hacer un Maxi, el país esta dividido en 2 y encima Icardi balance en esta época del año y tratar de entender profundiza la división. REFLEXIONES 20 que pasó y donde estamos parados o acostados como mi caso. En el ámbito judío seguimos luchando, acá entre Duran Barba y los descerebrados que Sin duda, la noticia mas importante del irrumpieron en la catedral le dieron laburo a la año vino de Roma -

1 Lahiton [email protected]

Lahiton [email protected] 1 Lahiton magazine was founded in 1969 by two partners, Uri Aloni and David Paz, and was funded by an investment from Avraham Alon, a Ramlah nightclub owner and promoter. Uri Aloni was a pop culture writer and rabid music fan while David Paz, another popular music enthusiast, was an editor who knew his way around the technical side of print production. The name “Lahiton,” reportedly invented by entertainers Rivka Michaeli and Ehud Manor, combines the Hebrew words for hit, “lahit” and newspaper, “iton.” Lahiton [email protected] 2 Uri Aloni cites the British fan magazines Melody Maker and New Music Express as influences; (Eshed 2008) while living in London and writing for the pop music columns of Yediot Ahronot and La-Isha, he would lift editorial content and photos from the latest British pop magazines, write articles, then find an Israel-bound traveler at the London airport to transport the articles into the hands of his editors. In Lahiton’s early days, Aloni and Paz continued this practice (Edut 2014). Eventually, however Lahiton’s flavor became uniquely secular Israeli. Although in 1965 the Beatles were famously denied permission to perform in Israel (Singer 2015), by the time Lahiton got started in 1969 there was no stemming the tide; the international pop music scene had permeated Israel’s insular and conservative culture. At the time there were no other Hebrew publications that covered what was going on both at home and in America and Europe. Lahiton began as a bimonthly publication, but within the first year, when press runs of 5000 copies sold out on a regular basis, Paz and Aloni turned it into a weekly. -

The Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion of Settler Colonialism: the Case of Palestine

NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS PROGRAM WHO IS ELIGIBLE TO EXIST? THE DYNAMICS OF INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION OF SETTLER COLONIALISM: THE CASE OF PALESTINE WALEED SALEM PhD THESIS NICOSIA 2019 WHO IS ELIGIBLE TO EXIST? THE DYNAMICS OF INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION OF SETTLER COLONIALISM: THE CASE OF PALESTINE WALEED SALEM NEAREAST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS PROGRAM PhD THESIS THESIS SUPERVISOR ASSOC. PROF. DR. UMUT KOLDAŞ NICOSIA 2019 ACCEPTANCE/APPROVAL We as the jury members certify that the PhD Thesis ‘Who is Eligible to Exist? The Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion of Settler Colonialism: The Case of Palestine’prepared by PhD Student Waleed Hasan Salem, defended on 26/4/2019 4 has been found satisfactory for the award of degree of Phd JURY MEMBERS ......................................................... Assoc. Prof. Dr. Umut Koldaş (Supervisor) Near East University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Department of International Relations ......................................................... Assoc. Prof.Dr.Sait Ak şit(Head of Jury) Near East University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Department of International Relations ......................................................... Assoc. Prof.Dr.Nur Köprülü Near East University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Department of Political Science ......................................................... Assoc. Prof.Dr.Ali Dayıoğlu European University of Lefke -

60Th Eurovision Song Contest 2015 Vienna / Austria 1St Semi Final 19Th May 2015

60th Eurovision Song Contest 2015 Vienna / Austria 1st Semi Final 19th May 2015 Country Participant Song My Notes My Points Rank Qualifer 1 Moldova Eduard Romanyuta I Want Your Love 2 Armenia Genealogy Face The Shadow 3 Belgium Loïc Nottet Rhythm Inside 4 Netherlands Trijntje Oosterhuis Walk Along 5 Finland Pertti Kurikan Nimipäivät Aina Mun Pitää 6 Greece Maria-Elena Kyriakou Last Breath 7 Estonia Elina Born & Stig Rästa Goodbye To Yesterday 8 FYR Macedonia Daniel Kajmakoski Autumn Leaves 9 Serbia Bojana Stamenov Beauty Never Lies 10 Hungary Boggie Wars For Nothing 11 Belarus Uzari & Maimuna Time 12 Russia Polina Gagarina A Million Voices 13 Denmark Anti Social Media The Way You Are 14 Albania Elhaida Dani I'm Alive 15 Romania Voltaj De La Capăt 16 Georgia Nina Sublati Warrior [email protected] http://www.eurovisionlive.com © eurovisionlive.com 60th Eurovision Song Contest 2015 Vienna / Austria 2nd Semi Final 21st May 2015 Country Participant Song My Notes My Points Rank Qualifier 1 Lithuania Monika & Vaidas This Time 2 Ireland Molly Sterling Playing With Numbers 3 San Marino Michele Perniola & Anita Simoncini Chain Of Lights 4 Montenegro Knez Adio 5 Malta Amber Warrior 6 N0rway Mørland & Debrah Scarlett A Monster Like Me 7 Portugal Leonor Andrade Há Um Mar Que Nos Separa 8 Czech Republic Marta Jandová & Václav Noid Bárta Hope Never Dies 9 Israel Nadav Guedj Golden Boy 10 Latvia Aminata Love Injected 11 Azerbaijan Elnur Huseynov Hour Of The Wolf 12 Iceland María Ólafsdóttir Unbroken 13 Sweden Måns Zelmerlöw Heroes 14 Switzerland Mélanie René Time To Shine 15 Cyprus Giannis Karagiannis One Thing I Should Have Done 16 Slovenia Maraaya Here For You 17 Poland Monika Kuszyńska In The Name Of Love [email protected] http://www.eurovisionlive.com © eurovisionlive.com.