Umar Ibn Al-Khattab's Visits to Bayt Al-Maqdis: a Study On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Join the MCA Mailing List and Stay Connected Advertisements Is Tuesday at 5:00 PM 2 46

PRAYER TIMINGS Effective 02/13 MCA NOOR Fajr 6:10 6:10 Dhuhr 12:35 12:35 Asr 3:45 4:30 Maghrib Sunset Sunset Isha 7:20 7:20 Juma 1 12:15 12:15 Juma 2 01:00 01:00 Newsletter Juma 2 01:45 01:45 Published Weekly by the Muslim Community Association of San Francisco Bay Area www.mcabayarea.org Jamadi ‘II 30, 1442 AH Friday, February 12, 2021 Grand Mosque of Brussels AL-QURAN And to Allah belong the best names, so invoke Him by them. And leave [the company of] those who practice deviation concerning His names.1 They will be recompensed for what they have been doing. Quran: 7:180 HADITH Narrated/Authority of Abdullah bin Amr: Once the Prophet remained behind us in a journey. He joined us while we were performing ablution for the prayer which was over-due. We were just passing wet hands over our feet (and not washing them properly) so the Prophet addressed us in a loud voice and said twice or thrice: “Save your heels from the fire.” Al-Bukhari: Ch 3, No. 57 Final Deadline to submit Join the MCA Mailing List and Stay Connected Advertisements is Tuesday at 5:00 PM www.mcabayarea.org/newsletter 2 46. Al-Hakeem (The Wise One) The Wise, The Judge of Judges, The One who is correct in His doings. “And to Allah belong the best names, so invoke Him by them.” [Quran 7:180] 3 Youth Corner Mahmoud’s Love for Basketball There was a boy who was 9 years old, standing tall at he didn’t like was every Friday night the basketball court the gate “HEY” and his adrenaline freezes, the ball 4 feet and 5 inches, and weighing a whole 90 pounds. -

Iran, Israel, the Persian Gulf, and the United States: a Conflict Resolution Perspective

Iran, Israel, the Persian Gulf, and the United States: A Conflict Resolution Perspective By Simon Tanios Abstract Where the Middle East is often described as a battleground between “chosen peoples”, Johan Galtung, the principal founder of the discipline of peace and conflict studies, preferred to see it as a conflict between “persecuted peoples”. Iran, Israel, the Persian Gulf, and the United States have been in various conflicts through history shaking peace in the Middle East, with a prevailing tense atmosphere in relations between many parties, despite some periods of relatively eased tensions or even strategic alliances. Nowadays, Iran considers the United States an arrogant superpower exploiting oppressed nations, while the United States sees Iran as irresponsible supporting terrorism. In sync with this conflict dynamic, on one hand, the conflict between Iran and many Gulf countries delineates important ideological, geopolitical, military, and economic concerns, and on the other hand, the conflict between Iran and Israel takes a great geopolitical importance in a turbulent Middle East. In this paper, we expose the main actors, attitudes, and behaviors conflicting in the Middle East region, particularly with regard to Iran, Israel, the Gulf countries, and the United States, describing the evolution of their relations, positions, and underlying interests and needs. Then, while building our work on the Galtung’s transcend theory for peace, we expose some measures that may be helpful for peace-making in the Middle East. Keywords: Iran; Israel; Gulf countries; the United States; conflict resolution. I. Introduction of Israel in the Muslim World, and the mutual animosity between Iran and the United States. -

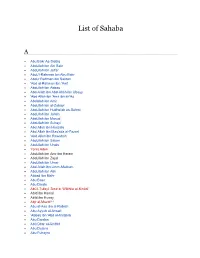

List of Sahaba

List of Sahaba A Abu Bakr As-Siddiq Abdullah ibn Abi Bakr Abdullah ibn Ja'far Abdu'l-Rahman ibn Abu Bakr Abdur Rahman ibn Sakran 'Abd al-Rahman ibn 'Awf Abdullah ibn Abbas Abd-Allah ibn Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy 'Abd Allah ibn 'Amr ibn al-'As Abdallah ibn Amir Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr Abdullah ibn Hudhafah as-Sahmi Abdullah ibn Jahsh Abdullah ibn Masud Abdullah ibn Suhayl Abd Allah ibn Hanzala Abd Allah ibn Mas'ada al-Fazari 'Abd Allah ibn Rawahah Abdullah ibn Salam Abdullah ibn Unais Yonis Aden Abdullah ibn Amr ibn Haram Abdullah ibn Zayd Abdullah ibn Umar Abd-Allah ibn Umm-Maktum Abdullah ibn Atik Abbad ibn Bishr Abu Basir Abu Darda Abū l-Ṭufayl ʿĀmir b. Wāthila al-Kinānī Abîd ibn Hamal Abîd ibn Hunay Abjr al-Muzni [ar] Abu al-Aas ibn al-Rabiah Abu Ayyub al-Ansari ‘Abbas ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib Abu Dardaa Abû Dhar al-Ghifârî Abu Dujana Abu Fuhayra Abu Hudhaifah ibn Mughirah Abu-Hudhayfah ibn Utbah Abu Hurairah Abu Jandal ibn Suhail Abu Lubaba ibn Abd al-Mundhir Abu Musa al-Ashari Abu Sa`id al-Khudri Abu Salama `Abd Allah ibn `Abd al-Asad Abu Sufyan ibn al-Harith Abu Sufyan ibn Harb Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah Abu Zama' al-Balaui Abzâ al-Khuzâ`î [ar] Adhayna ibn al-Hârith [ar] Adî ibn Hâtim at-Tâî Aflah ibn Abî Qays [ar] Ahmad ibn Hafs [ar] Ahmar Abu `Usayb [ar] Ahmar ibn Jazi [ar][1] Ahmar ibn Mazan ibn Aws [ar] Ahmar ibn Mu`awiya ibn Salim [ar] Ahmar ibn Qatan al-Hamdani [ar] Ahmar ibn Salim [ar] Ahmar ibn Suwa'i ibn `Adi [ar] Ahmar Mawla Umm Salama [ar] Ahnaf ibn Qais Ahyah ibn -

Mu'awiyah Ibn Abi Sufyan

The Biography Of Muawiyah Ibn Sufiyan His successor son Yazid and the Martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali A Reader’s Series ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Written By: Maulvi Abdul Aziz Published By: Darussalam Publishers & Distributers Copyright: Darussalam Publishers ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic of mechanical, including photocopying and recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. Contents Publisher's Note ............................................................................................................................................. 6 The Umayyads ............................................................................................................................................... 7 The Early Life of Mu’awiyah ........................................................................................................................ 9 Mu’awiyah ibn Abi Sufyan: A Companion of the Prophet (Peace & Blessings of Allah be upon him) .... 11 Mu’awiyah during the Caliphate of Uthman and the Formation of the Navy ............................................. 13 Mu’awiyah as Governor of Syria ................................................................................................................ 14 Mu’awiyah as the Caliph of the Entire Muslim -

Early Muslim Legal Philosophy

EARLY MUSLIM LEGAL PHILOSOPHY Identity and Difference in Islamic Jurisprudence OUSSAMA ARABI Copyright 1999, G.E. von Grunebaum Center for Near Eastern Studies University of California, Los Angeles In Loving Memory of My Father Author’s Note owe special thanks to the Faculty and Staff of the G.E. von IGrunebaum Center for Near Eastern Studies at the Univer- sity of California, Los Angeles, where the research for this pa- per was conducted in the spring and summer of 1995. In particular, my thanks go to the Center’s Director, Professor Irene Bierman, Assistant Director Jonathan Friedlander, Research Associate Dr. Samy S. Swayd, Professor Michael Morony, and Senior Editor Diane James. All dates in the text unspecified as to calendar are Hijri dates. Introduction here is an essential relation between identity and reli- Tgion in human societies. Among the pre-Islamic Arabs, this connection found expression in the identification estab- lished between the Arab tribes, their mythical progenitors and their respective gods. Each tribe had its own privileged god(s), and the great grandfather of the tribe — a half-human, half- divine figure — was conceived as responsible for the introduc- tion of the worship of that specific god. These aspects of group identity point to a tripartite structure comprising kinship, re- ligion and identity in intricate combination. It would be a fascinating course of inquiry to trace the incidence of mono- theism in the complex identity structure of pre-Islamic Arab communities. In this paper I examine the repercussions of monotheistic Islam on a specific cultural product, viz., legal discourse, investigating the issue of the unitary identity of Is- lamic law as this identity transpires in both the legal philoso- phy and the practice of Islamic law during its formative period in the second century of Islam. -

Descargar Descargar

Opción, Año 35, Especial No.23 (2019): 1130-1139 ISSN 1012-1587/ISSNe: 2477-9385 The historical starting points for the statehood of umayyad caliphate Saad Kadhim Abd Al-Janabi, Ahmed Jabar Jamr al-Hilali [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This research aims at studying the factors of the establishment of the Umayyad caliphate through the history of Al-Tabari (The History of the Prophets and Kings) who has passed away in 310 A.H, through comparing his stories with the other Islamic history resources. As a result, some of the historians who preceded Al-Tabari agreed that Abu Bakr made Yazid the Caliph of Syria in order to create the Umayyad caliphate. In conclusion, the killing of Ali bin Abi Talib is among the most important factors that precipitated the establishment of the Umayyad Caliphate. Keywords: Historical, Starting, Statehood, Umayyad Caliphate. Los puntos de partida históricos para la estadidad del califato omeya Resumen Esta investigación tiene como objetivo estudiar los factores del establecimiento del califato omeya a través de la historia de Al-Tabari (La historia de los profetas y reyes) que falleció en 310 A.H, comparando sus historias con los otros recursos de la historia islámica. Como resultado, algunos de los historiadores que precedieron a Al- Tabari acordaron que Abu Bakr convirtió a Yazid en el califa de Siria para crear el califato omeya. En conclusión, el asesinato de Ali bin Abi Talib es uno de los factores más importantes que precipitó el establecimiento del califato omeya. Palabras clave: Histórico, Comienzo, Estado, Califato omeya. Recibido: 20-02-2019 Aceptado: 20-06-2019 1131 Saad Kadhim Abd Al-Janabi et al. -

Da* Wain Islamic Thought: the Work Of'abd Allah Ibn 'Alawl Al-Haddad

Da* wa in Islamic Thought: the Work o f'Abd Allah ibn 'Alawl al-Haddad By Shadee Mohamed Elmasry University of London: School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD. ProQuest Number: 10672980 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672980 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT Imam 'Abd Allah ibn 'Alawi al-Haddad was bom in 1044/1634, he was a scholar of the Ba 'Alawi sayyids , a long line of Hadrami scholars and gnostics. The Imam led a quiet life of teaching and, although blind, travelled most of Hadramawt to do daw a, and authored ten books, a diwan of poetry, and several prayers. He was considered the sage of his time until his death in Hadramawt in 1132/1721. Many chains of transmission of Islamic knowledge of East Africa and South East Asia include his name. Al-Haddad’s main work on da'wa, which is also the core of this study, is al-Da'wa al-Tdmma wal-Tadhkira al-'Amma (The Complete Call and the General Reminder ). -

Sources, Sunni and Shi'a: Succession and Imams What

C.T.R. Hewer: GCSE Islam, Sources, Sunni and Shi'a: Succession and Imams, Background 1, page 1 Background article: Sources, Sunni and Shi'a: Succession and Imams What happened after Muhammad? The Sunni view There are some questions in the lives of all societies that appear not to have a resolution but which require us to understand the different positions of all parties. The question of what should have happened about the leadership of the Muslim community after the death of Muhammad is one of them. In this article, we explore the Sunni view. The word Sunni is derived from the term sunna or the customary practice of Muhammad. All Muslims will say that they follow the sunna but the term Sunni relates to the largest group amongst Muslims worldwide, who are found throughout the world. They comprise some eighty-five to ninety per cent of all Muslims. Central to their position is that God did not decree in the Qur'an who was to follow Muhammad, what kind of a leadership that should be, or how the question of selecting a new leader should be organised. Further, they hold that Muhammad did not nominate his successor or say how the new leader should be selected. God and Muhammad were silent on the question; therefore it was left up to the community to resolve. Some things were clear. The most important is that Muhammad was the last prophet and so there was no question of someone taking his place directly as God’s messenger amongst them. The community was to be led according to the Qur'an and the lived example of Muhammad, the Sunna. -

Islam and International Law

Volume 87 Number 858 June 2005 Islam and international law Sheikh Wahbeh al-Zuhili* Dr Sheikh Wahbeh M. al-Zuhili is professor and head of the Islamic Law (fi qh) and Doctrines Department of the Faculty of Shari’a, University of Damascus. He is the author of several books and studies on major issues related in particular to Islamic law. They include The eff ects of war in Islamic law: A comparative study, and at-tafseer al-muneer (Exegesis of the Holy Qur’an), dar al-fi kr, Damascus, 17 vols. Abstract This article by an Islamic scholar describes the principles governing international law and international relations from an Islamic viewpoint. After presenting the rules and principles governing international relations in the Islamic system, the author emphasizes the principles of sovereignty and non-interference in the internal affairs of other States and the aspiration of Islam to peace and harmony. He goes on to explain the relationship between Muslims and others in peacetime or in the event of war and the classical jurisprudential division of the world into the abode of Islam (dar al-islam) and that of war (dar al-harb). Lastly he outlines the restrictions imposed upon warfare by Islamic Shari’a law which have attained the status of legal rules. : : : : : : : While the voices of “the clash of civilizations” are echoing loud, and the so- called “war on terror” is influencing the fate of some communities and many groups of individuals in various countries of the world, it is appropriate to recall the humanitarian values that rally nations and peoples around them. -

Kecemerlangan Futuhat Islamiyyah Era Khulafa' Al-Rashidin

KECEMERLANGAN FUTUHAT ISLAMIYYAH ERA KHULAFA’ AL-RASHIDIN (The Excellence of Futuhat Islamiyyah in the Era of Khulafa’ Al-Rashidin) Ermy Azziaty Rozali* Zamri Ab Rahman** Abstrak Zaman Khulafa’ al-Rashidin merupakan antara “era keemasan” pemerintahan dan ketamadunan Islam. Hal ini kerana, sungguhpun kuasa Islam baru bertapak di persada dunia, namun secara pantas pesaing baru ini dapat menguasai dua pertiga dunia yang menyaksikan kehancuran empayar Rom dan Parsi, dua buah kuasa besar yang telah lama mendominasi aktiviti penaklukan wilayah-wilayah baru ketika itu. Justeru, artikel ini akan membahaskan mengenai kecemerlangan futuhat yang telah dicapai oleh setiap khalifah di zaman masing- masing yang telah memberi sumbangan melonjakkan kehebatan Islam. Artikel ini menggunakan pendekatan analisis kandungan terhadap pelbagai sumber primer dan sekunder. Kajian dilakukan berdasarkan kaedah analisis sejarah terhadap peristiwa yang berlaku. Hasil kajian ini menunjukkan bahawa kecemerlangan futuhat di zaman Khulafa’ al-Rashidin menjadikan sebahagian besar wilayah kekuasaan Empayar Rom di bahagian Timur Tengah, Mesir dan Afrika Utara berjaya ditakluki dan dibuka oleh tentera Islam. Pada masa yang sama, pemerintahan Islam juga dapat menghancurkan empayar Parsi yang terpaksa menyerahkan seluruh wilayah kekuasaannya di bahagian Timur kepada tentera Islam. Kecemerlangan futuhat ini lebih manis lagi apabila penguasaan Islam turut meluas ke wilayah bukan Arab dengan jayanya seperti di Armenia, Azerbayjan, Tabaristan dan sebagainya. Kata kunci: Kecemerlangan, Futuhat Islamiyyah, Khulafa’ al-Rashidin, Sejarah Islam, Rom, Parsi Abstract The Khulafa’ al-Rashidin era is among the “golden age” of Islamic governance and civilization. This is because, albeit being a new power in the eyes of the world, this new competitor swiftly dominated two-thirds of the world by witnessing the downfall of the Rome and Persian empires, the two major powers that had long dominated the conquest activity of new areas of that time. -

Islamic and Syriac Christian Apocalypses of the 7Th and 8Th Centuries

Islamic and Syriac Christian Apocalypses of the 7th and 8th Centuries Christopher WRIGHT, The Citadel Those who study the first two centuries of Islamic history must rely upon a limited number of viable contemporary sources. As a result, every minutia of information, conventional and non-conventional alike, must be utilized in order to reconstruct the events of that era. One genre that has received little attention by historians of this era is that of Apocalypses. Apocalypses have been exam- ined and studied at great length by generations of scholars, but rarely by the historian. This is because most of the best known Jewish and Christian apoca- lypses were written during a period where other documentary and narrative sources are abundant (ALEXANDER, 1978: XIII). Thus there has been little in- centive to resort to apocalyptic texts for such historical data. On the contrary, seventh and eighth century Islamic history has not provided us with a rich se- lection of documentation, and thus an examination of apocalyptic writings may provide missing historical information not available from other, more conven- tional sources. The greater scope of my study is an examination of Syriac Christian apoca- lypses and Arabic Muslim apocalypses written during the Islamic Conquest of the Byzantine east. This work however, will primarily focus on my findings within the Islamic sources. In the late seventh and early eighth centuries many people, Christian and Muslim alike, were convinced that the end of the world was drawing near. Christians were witnessing their world being turned upside down by the Arab conquests, and to make matters worse, these successful con- quests were being accomplished in the name of God. -

The Islamic Openings

THE ISLAMIC OPENINGS (AI-Fatuhat AI-lslamiyah) by `Abdul `Aziz Al-Shinnawy Translated by Heba Samir Hendawi Revised by AElfwine Acelas Mischler www.islambasics.com CONTENTS Notes on the Translation............................................ The Opening of Makkah ............................................. The Opening of Iraq.................................................... The Opening of Al-Mada'in......................................... The Opening of Al-Sham ............................................ The Opening of Jerusalem......................................... The Opening of Egypt................................................. The Opening of Alexandria ........................................ The Opening of Persia................................................ The Opening of Iraq 2................................................. The Opening of Khurasan .......................................... The Opening of North Africa ...................................... The Opening of Cyprus... ........................................... The Opening of Constantinople................................. The Opening of Andalusia.......................................... References.................................................................. www.islambasics.com NOTES ON THE TRANSLATION We have rejected the traditional translation of fataha as "conquered" in favor of "opened". Thus the English title of this book is The Islamic Openings rather than The Islamic Conquests. In the military context, fataha is usually applied only to