Sources, Sunni and Shi'a: Succession and Imams What

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Join the MCA Mailing List and Stay Connected Advertisements Is Tuesday at 5:00 PM 2 46

PRAYER TIMINGS Effective 02/13 MCA NOOR Fajr 6:10 6:10 Dhuhr 12:35 12:35 Asr 3:45 4:30 Maghrib Sunset Sunset Isha 7:20 7:20 Juma 1 12:15 12:15 Juma 2 01:00 01:00 Newsletter Juma 2 01:45 01:45 Published Weekly by the Muslim Community Association of San Francisco Bay Area www.mcabayarea.org Jamadi ‘II 30, 1442 AH Friday, February 12, 2021 Grand Mosque of Brussels AL-QURAN And to Allah belong the best names, so invoke Him by them. And leave [the company of] those who practice deviation concerning His names.1 They will be recompensed for what they have been doing. Quran: 7:180 HADITH Narrated/Authority of Abdullah bin Amr: Once the Prophet remained behind us in a journey. He joined us while we were performing ablution for the prayer which was over-due. We were just passing wet hands over our feet (and not washing them properly) so the Prophet addressed us in a loud voice and said twice or thrice: “Save your heels from the fire.” Al-Bukhari: Ch 3, No. 57 Final Deadline to submit Join the MCA Mailing List and Stay Connected Advertisements is Tuesday at 5:00 PM www.mcabayarea.org/newsletter 2 46. Al-Hakeem (The Wise One) The Wise, The Judge of Judges, The One who is correct in His doings. “And to Allah belong the best names, so invoke Him by them.” [Quran 7:180] 3 Youth Corner Mahmoud’s Love for Basketball There was a boy who was 9 years old, standing tall at he didn’t like was every Friday night the basketball court the gate “HEY” and his adrenaline freezes, the ball 4 feet and 5 inches, and weighing a whole 90 pounds. -

The Islamic State

The Group That Calls Itself a State: Understanding the Evolution and Challenges of the Islamic State The Group That Calls Itself a State: Understanding the Evolution and Challenges of the Islamic State Muhammad al-‘Ubaydi Nelly Lahoud Daniel Milton Bryan Price THE COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER AT WEST POINT www.ctc.usma.edu December 2014 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 6 Metamorphosis: From al-Tawhid wa-al-Jihad to Dawlat al-Khilafa (2003-2014) ........... 8 A Society (mujtama‘) in the Making During Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi’s Era ................. 9 The March to “Statehood”.................................................................................................... 14 Parting Ways with al-Qa’ida .............................................................................................. 16 What is the difference between the “Islamic state” of 2006 and that of 2014? ............ 18 The Sectarian Factor .............................................................................................................. 19 Goals and Methods: Comparing Three Militant Groups.................................................. 27 The Islamic State: An Adaptive Organization Facing Increasing Challenges .............. 36 Trends in IS Military Operations ....................................................................................... -

The Islamic Caliphate: a Controversial Consensus

The Islamic Caliphate: A Controversial Consensus Ofir Winter The institution of the caliphate is nearly as old as Islam itself. Its roots lie in the days following the death of Muhammad in 632, when the Muslims convened and chose a “caliph” (literally “successor” or “deputy”). While the Shiites recognize ʿAli b. Abi Talib as the sole legitimate heir of the prophet, the Sunnis recognize the first four “rightly guided” caliphs (al-Khulafa al-Rashidun), as well as the principal caliphates that succeeded them – the Umayyad, Abbasid, Mamluk, and Ottoman. The caliphate ruled the Sunni Muslim world for nearly 1,300 years, enjoying relative hegemony until its abolition in 1924 by Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey. Although Sunni commentators have defined the essence of the caliphate differently in different periods, they tend to agree that the caliphate was founded for the purpose of managing Muslim affairs in accordance with the laws of God and organizing the lives of their people according to the principles of Islamic religious law.1 In practice, the caliphate has experienced highs and lows over the course of its history. In some periods, it exerted authority over political, administrative, financial, legal, and military affairs; in others, it was reduced to the symbolic and spiritual realm, such as leading mass prayers, much in the manner of the modern Catholic papacy.2 The Islamic State’s 2014 announcement on the renewal of the caliphate showed that the institution is not only a governmental-religious institution of the past, but also a living and breathing ideal that excites the imagination of present day Muslims. -

Iran, Israel, the Persian Gulf, and the United States: a Conflict Resolution Perspective

Iran, Israel, the Persian Gulf, and the United States: A Conflict Resolution Perspective By Simon Tanios Abstract Where the Middle East is often described as a battleground between “chosen peoples”, Johan Galtung, the principal founder of the discipline of peace and conflict studies, preferred to see it as a conflict between “persecuted peoples”. Iran, Israel, the Persian Gulf, and the United States have been in various conflicts through history shaking peace in the Middle East, with a prevailing tense atmosphere in relations between many parties, despite some periods of relatively eased tensions or even strategic alliances. Nowadays, Iran considers the United States an arrogant superpower exploiting oppressed nations, while the United States sees Iran as irresponsible supporting terrorism. In sync with this conflict dynamic, on one hand, the conflict between Iran and many Gulf countries delineates important ideological, geopolitical, military, and economic concerns, and on the other hand, the conflict between Iran and Israel takes a great geopolitical importance in a turbulent Middle East. In this paper, we expose the main actors, attitudes, and behaviors conflicting in the Middle East region, particularly with regard to Iran, Israel, the Gulf countries, and the United States, describing the evolution of their relations, positions, and underlying interests and needs. Then, while building our work on the Galtung’s transcend theory for peace, we expose some measures that may be helpful for peace-making in the Middle East. Keywords: Iran; Israel; Gulf countries; the United States; conflict resolution. I. Introduction of Israel in the Muslim World, and the mutual animosity between Iran and the United States. -

Understanding the Role of Khalifa for the Foundation of Wizard Khalifa Tourism

Understanding the Role of Khalifa for the Foundation of Wizard Khalifa Tourism Understanding the Role of Khalifa for the Foundation of Wizard Khalifa Tourism A.A.M. Any1, N.N. Ahmat2, A. Robani2, F.S. Fen3, S.A. Abas4 and M. Saad4 1Islamic Tourism Center, Ministry of Tourism and Culture 2Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka, Center for Languages and Human Development 3Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka, Faculty of Technology Management and Technopreneurship 4International Islamic University of Malaysia, Faculty of Languages and Management [email protected] Abstract—Branding has helped Malaysian among Islamic religious groups or orders. The tourism industry moving forward in this highly famous Caliphates were the 4 khalifas after the competitive world. Till now these Malaysian death of Prophet Muhammad SAW. However, brands such as Malaysia Truly Asia or Muslim for this article, the term khaleefa is firstly referred friendly country or Halal friendly country are still is when Allah command the angels to bow relevant but a new perspective toward Malaysia is down to Adam as in 2:30 in which give a clear a need. Thus, this research aimed to offer a new root meaning of vicegerent. The ayaat is {and approach of tourism branding that would put [mention, O Muhammad], when your Lord said Malaysian in the map of the world again. This to the angels, "Indeed, I will make upon the new approach of branding is a concept of Wizard earth a successive authority." They said, "Will Khalifa Tourism (WKT). It was introduced to You place upon it one who causes corruption relook philosophically at the role of mankind that therein and sheds blood, while we declare Your man is not a lord on earth but merely as a tourist praise and sanctify You?" Allah said, "Indeed, I in this world. -

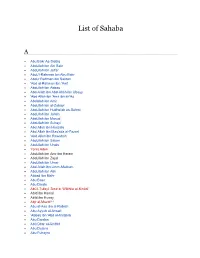

List of Sahaba

List of Sahaba A Abu Bakr As-Siddiq Abdullah ibn Abi Bakr Abdullah ibn Ja'far Abdu'l-Rahman ibn Abu Bakr Abdur Rahman ibn Sakran 'Abd al-Rahman ibn 'Awf Abdullah ibn Abbas Abd-Allah ibn Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy 'Abd Allah ibn 'Amr ibn al-'As Abdallah ibn Amir Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr Abdullah ibn Hudhafah as-Sahmi Abdullah ibn Jahsh Abdullah ibn Masud Abdullah ibn Suhayl Abd Allah ibn Hanzala Abd Allah ibn Mas'ada al-Fazari 'Abd Allah ibn Rawahah Abdullah ibn Salam Abdullah ibn Unais Yonis Aden Abdullah ibn Amr ibn Haram Abdullah ibn Zayd Abdullah ibn Umar Abd-Allah ibn Umm-Maktum Abdullah ibn Atik Abbad ibn Bishr Abu Basir Abu Darda Abū l-Ṭufayl ʿĀmir b. Wāthila al-Kinānī Abîd ibn Hamal Abîd ibn Hunay Abjr al-Muzni [ar] Abu al-Aas ibn al-Rabiah Abu Ayyub al-Ansari ‘Abbas ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib Abu Dardaa Abû Dhar al-Ghifârî Abu Dujana Abu Fuhayra Abu Hudhaifah ibn Mughirah Abu-Hudhayfah ibn Utbah Abu Hurairah Abu Jandal ibn Suhail Abu Lubaba ibn Abd al-Mundhir Abu Musa al-Ashari Abu Sa`id al-Khudri Abu Salama `Abd Allah ibn `Abd al-Asad Abu Sufyan ibn al-Harith Abu Sufyan ibn Harb Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah Abu Zama' al-Balaui Abzâ al-Khuzâ`î [ar] Adhayna ibn al-Hârith [ar] Adî ibn Hâtim at-Tâî Aflah ibn Abî Qays [ar] Ahmad ibn Hafs [ar] Ahmar Abu `Usayb [ar] Ahmar ibn Jazi [ar][1] Ahmar ibn Mazan ibn Aws [ar] Ahmar ibn Mu`awiya ibn Salim [ar] Ahmar ibn Qatan al-Hamdani [ar] Ahmar ibn Salim [ar] Ahmar ibn Suwa'i ibn `Adi [ar] Ahmar Mawla Umm Salama [ar] Ahnaf ibn Qais Ahyah ibn -

Mu'awiyah Ibn Abi Sufyan

The Biography Of Muawiyah Ibn Sufiyan His successor son Yazid and the Martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali A Reader’s Series ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Written By: Maulvi Abdul Aziz Published By: Darussalam Publishers & Distributers Copyright: Darussalam Publishers ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic of mechanical, including photocopying and recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. Contents Publisher's Note ............................................................................................................................................. 6 The Umayyads ............................................................................................................................................... 7 The Early Life of Mu’awiyah ........................................................................................................................ 9 Mu’awiyah ibn Abi Sufyan: A Companion of the Prophet (Peace & Blessings of Allah be upon him) .... 11 Mu’awiyah during the Caliphate of Uthman and the Formation of the Navy ............................................. 13 Mu’awiyah as Governor of Syria ................................................................................................................ 14 Mu’awiyah as the Caliph of the Entire Muslim -

Sample E 1 of 21

Sample E 1 of 21 1 The Islamic Caliphate: Legitimate Today? March 24, 2016 AP Capstone: Research Sample E 2 of 21 2 AP Research March 24, 2016 The Islamic Caliphate: Legitimate Today? When the Islamic State declared itself a caliphate in June 2014, an old ideological wound was ripped open, raising questions in the minds of Muslims around the globe (Bradley). The Islamic State’s declaration was universally deemed the most significant development in international Jihadism since 9/11 (Bradley). The term caliphate comes from the Arabic word khilāfa, which means “succession” or “representation” (Sowerwine). The caliphate is an Islamic form of government which continues the Prophet Muhammad's rule, follows Sharia’a law, and seeks worldwide Muslim allegiance (Black). The declaration of a caliphate by the Islamic State has brought the caliphate back onto the sociopolitical scene, raising many questions. Is the caliphate a Muslim ideal, or is it a means of political manipulation that has been exploited throughout the centuries? Is the caliphate consistent with the founding beliefs of Islam, or is it an ideological intrusion that is outofstep with the religion? To address this question, this paper will analyze the historical context of the caliphate and of the Qur’an itself. Review of Major Literature Concerning the Caliphate The Islamic State’s declaration has generated significant debate in the Islamic scholarly community. Some claim that the caliphate is an extremist interpretation of the Qur’an, while others believe the caliphate to be a legitimate Muslim requirement (Black). Scholarly literature addressing the idea of a caliphate sharply divides along fault lines of Islamic theology. -

Death of the Caliphate: Reconfiguring Ali Abd Al-Raziq's Ideas and Legacy

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 Death of the Caliphate: Reconfiguring Ali Abd al-Raziq’s Ideas and Legacy Arooj Alam The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3209 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] DEATH OF THE CALIPHATE: RECONFIGURING ALI ABD AL-RAZIQ’S IDEAS AND LEGACY by AROOJ ALAM A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Middle Eastern Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York. 2019 © 2019 AROOJ ALAM All Rights Reserved ii Death of the Caliphate: Reconfiguring Ali Abd al-Raziq’s ideas and legacy by Arooj Alam This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Middle Eastern Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. _______________ _________________________________________________ Date Samira Haj Thesis Advisor _______________ ________________________________________________ Date Simon Davis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Death of the Caliphate: Reconfiguring Ali Abd al-Raziq’s ideas and legacy by Arooj Alam Advisor: Professor Samira Haj The demise of the Ottoman Caliphate in 1924 generated vigorous debates throughout the Muslim world regarding the political future of the Ummah. While several prominent Muslim thinkers contributed to this “Caliphate debate,” none left as contested a legacy as the Egyptian intellectual, ‘Ali ‘Abd al-Raziq (1888-1966). -

Chapter 1 Sufi Regional Cults in South Asia and Indonesia

Chapter 1 Sufi Regional Cults in South Asia and Indonesia: Towards a Comparative Analysis Pnina Werbner Introduction To compare Sufi orders across different places separated by thousands of miles of sea and land, and by radically different cultural milieus, is in many senses to seek the global in the local rather than the local in the global. Either way, charting difference and similarity in Sufism as an embodied tradition re- quires attention, beyond mystical philosophical and ethical ideas, to the ritual performances and religious organizational patterns that shape Sufi orders and cults in widely separated locations. We need, in other words, to seek to under- stand comparatively four interrelated symbolic complexes: first, the sacred division of labor—the ritual roles that perpetuate and reproduce a Sufi order focused on a particular sacred center; second, sacred exchanges between places and persons, often across great distances; third, the sacred ‘region’, its catchment area, and the sanctified central places that shape it; and fourth, the sacred indexical events—the rituals—that co-ordinate and revitalize organiza- tional and symbolic unities and enable managerial and logistical planning and decision making. Comparison requires that we examine the way in which these four dimensions of ritual sanctification and performance are linked, and are embedded in a particular symbolic logic and local environment. In this chapter I use the notion of ‘cult’ in its anthropological sense, i.e. to refer to organized ritual and symbolic practices performed in space and over time, often cyclically, by a defined group of devotees, kinsmen, initiates, sup- plicants, pilgrims, or disciples. -

1 the Evolution of Meaning of the Qur'ānic Word “Khalīfa”

1 The Evolution of Meaning of the Qur’ānic Word “Khalīfa” Introduction The Qur’ānic word khalīfa has evolved in meaning from the time of Qur’ānic revelation to modern day. The earliest Qur’ānic exegetes seem to have understood this word as succession of previous generations. However, with the rise of the Umayyad caliphate thirty years after the death of the Prophet Muḥammad, the word began to acquire new connotations. Umayyad caliphs and their supporters often used the phrase Khalīfat Allāh (God’s deputy), perhaps to imply that God appointed the caliph. However, the word gradually became understood as “representative of God.” This notion that humans represent God has persisted until the present day. In addition to the vicegerency meaning, the word has also come to connote the position of “steward of the earth” and hence acquired a further ecological dimension. In this paper, I will argue that both renderings of the Qur’ānic word “khalīfa” as “God’s vicegerent” and “steward” are lexically inaccurate and theologically problematic. This will be accomplished by introducing the controversy surrounding the Qur'ānic notion of “khalīfa.” A chronological development of this word through an investigation of the lexical treatment of the word “khalīfa” in Arabic and Arabic-English dictionaries, encyclopedias, Qur’ānic exegesis, and other scholarly works. I will also be arguing that the meaning of “succession” seems to be the soundest interpretation of the term “khalīfa” because the “vicegerent” rendering may contradict the Qur’ānic emphasis on God’s oneness (tawḥīd), whereas the “stewardship” rendering is a modern-day interpretation, not understood at the time of Qur’ānic revelation. -

Pakistan, the Deoband ‘Ulama and the Biopolitics of Islam

THE METACOLONIAL STATE: PAKISTAN, THE DEOBAND ‘ULAMA AND THE BIOPOLITICS OF ISLAM by Najeeb A. Jan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Juan R. Cole, Co-Chair Professor Nicholas B. Dirks, Co-Chair, Columbia University Professor Alexander D. Knysh Professor Barbara D. Metcalf HAUNTOLOGY © Najeeb A. Jan DEDICATION Dedicated to my beautiful mother Yasmin Jan and the beloved memory of my father Brian Habib Ahmed Jan ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people to whom I owe my deepest gratitude for bringing me to this stage and for shaping the world of possibilities. Ones access to a space of thought is possible only because of the examples and paths laid by the other. I must begin by thanking my dissertation committee: my co-chairs Juan Cole and Nicholas Dirks, for their intellectual leadership, scholarly example and incredible patience and faith. Nick’s seminar on South Asia and his formative role in Culture/History/Power (CSST) program at the University of Michigan were vital in setting the critical and interdisciplinary tone of this project. Juan’s masterful and prolific knowledge of West Asian histories, languages and cultures made him the perfect mentor. I deeply appreciate the intellectual freedom and encouragement they have consistently bestowed over the years. Alexander Knysh for his inspiring work on Ibn ‘Arabi, and for facilitating several early opportunity for teaching my own courses in Islamic Studies. And of course my deepest thanks to Barbara Metcalf for unknowingly inspiring this project, for her crucial and sympathetic work on the Deoband ‘Ulama and for her generous insights and critique.