The Rules of Autogeddon: Sex Death and Law in JG Ballard's Crash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Considering Female Sexual Desire

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Re-Considering Female Sexual Desire: Internalized Representations Of Parental Relationships And Sexual Self- Concept In Women With Inhibited And Heightened Sexual Desire Eugenia Cherkasskaya Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/317 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] RE-CONSIDERING FEMALE SEXUAL DESIRE: INTERNALIZED REPRESENTATIONS OF PARENTAL RELATIONSHIPS AND SEXUAL SELF-CONCEPT IN WOMEN WITH INHIBITED AND HEIGHTENED SEXUAL DESIRE BY EUGENIA CHERKASSKAYA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Clinical Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ii ©2014 EUGENIA CHERKASSKAYA All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Clinical Psychology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Margaret Rosario, Ph.D. _________________ _______________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Maureen O’Connor _________________ ________________________________________ Date Executive Officer Diana Diamond, Ph.D. Lissa Weinstein, Ph.D. Deborah Tolman, Ed.D Diana Puñales, Ph.D. Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract RE-CONSIDERING FEMALE SEXUAL DESIRE: INTERNALIZED REPRESENTATIONS OF PARENTAL RELATIONSHIPS AND SEXUAL SELF-CONCEPT IN WOMEN WITH INHIBITED AND HEIGHTENED SEXUAL DESIRE by Eugenia Cherkasskaya Adviser: Margaret Rosario, Ph.D. -

Disciplining Sexual Deviance at the Library of Congress Melissa A

FOR SEXUAL PERVERSION See PARAPHILIAS: Disciplining Sexual Deviance at the Library of Congress Melissa A. Adler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Library and Information Studies) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 5/8/2012 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Christine Pawley, Professor, Library and Information Studies Greg Downey, Professor, Library and Information Studies Louise Robbins, Professor, Library and Information Studies A. Finn Enke, Associate Professor, History, Gender and Women’s Studies Helen Kinsella, Assistant Professor, Political Science i Table of Contents Acknowledgements...............................................................................................................iii List of Figures........................................................................................................................vii Crash Course on Cataloging Subjects......................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Setting the Terms: Methodology and Sources.......................................................5 Purpose of the Dissertation..........................................................................................6 Subject access: LC Subject Headings and LC Classification....................................13 Social theories............................................................................................................16 -

Mario Mieli, an Italian, Came to London in 1971 As a Student and Joined the Gay Liberation Front

I : ' ! L. ' m�ttiOI rhielii: I I Lj l . , 1 . :. , , , , , , . , . , " . , rt1 . · . +: ' 1h��6�eXuality{ '& ! : 1,1 : ;-- i i � . ; ; : ' : j I : l 1 __: : ; l �- · · : . b L +-+I : · · ·Lr - · · rat11ri-"'- r1 · 1 · · �� �'0�. ; . ; .. i ! ··'--!- l . ! � I I .l ' I W1�1�fs i 1 '.I �f 9aY .J� .�I• I - i � . · I . _I l. ! ! � ; 'i .Ii I i -1 . :. .J _ J I ; i i i ! I . : I li ' i I L -1-- ) I i i i 1 __ I ... ! I I_ . ; � - Gay Men's Press is an independent publishing project intending to produce books relevant to the male gay movement and to promote the ideas of gay liberation. Mario Mieli, an Italian, came to London in 1971 as a student and joined the Gay Liberation Front. The following year he returned to Italy, where he helped to found FUORJ!, the radicaJ gay movement and magazine, in which he has remained active for many years. mario mieli homosexuality and liberation elements of a gay critique translated by david fernbach GAY MEN'S PHESS LONDON First published in Great Britain 1980 by Gay Men's Press Copyright© 1977 Giulio Einaudi editori s.p.a., Turin, Italy Translation, Introduction and English edition Copyright © 1980 Gay Men's Press, 27 Priory Avenue, London N8 7RN. British LibraryCataloguing in Publication Data Mieli, Mario Homosexuality and Liberation. 1 .Homosexuality I. Title 300 HQ76.8.US ISBN O 907040 01 2 Typeset by Range Left Photosetters, London Cover printed by Spider Web Offset, London Printed and bound in Great Britain by A. Wheaton and Company Limited, Exeter Introduction by David Fernbach 7 Preface 18 Chapter One: Homosexual Desire is Universal 21 The Gay Movement Against Oppression 1. -

Radical Psychoanalysis

RADICAL PSYCHOANALYSIS Only by the method of free-association could Sigmund Freud have demonstrated how human consciousness is formed by the repression of thoughts and feelings that we consider dangerous. Yet today most therapists ignore this truth about our psychic life. This book offers a critique of the many brands of contemporary psychoanalysis and psychotherapy that have forgotten Freud’s revolutionary discovery. Barnaby B. Barratt offers a fresh and compelling vision of the structure and function of the human psyche, building on the pioneering work of theorists such as André Green and Jean Laplanche, as well as contemporary deconstruction, feminism, and liberation philosophy. He explores how “drive” or desire operates dynamically between our biological body and our mental representations of ourselves, of others, and of the world we inhabit. This dynamic vision not only demonstrates how the only authentic freedom from our internal imprisonments comes through free-associative praxis, it also shows the extent to which other models of psychoanalysis (such as ego-psychology, object-relations, self-psychology, and interpersonal-relations) tend to stray disastrously from Freud’s original and revolutionary insights. This is a vision that understands the central issues that imprison our psychic lives—the way in which the reflections of consciousness are based on the repression of our innermost desires, the way in which our erotic vitality is so often repudiated, and the way in which our socialization oppressively stifles our human spirit. Radical Psychoanalysis restores to the discipline of psychoanalysis the revolutionary impetus that has so often been lost. It will be essential reading for psychoanalysts, psychoanalytic psychotherapists, mental health practitioners, as well as students and academics with an interest in the history of psychoanalysis. -

List of Paraphilias

List of paraphilias Paraphilias are sexual interests in objects, situations, or individuals that are atypical. The American Psychiatric Association, in its Paraphilia Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM), draws a Specialty Psychiatry distinction between paraphilias (which it describes as atypical sexual interests) and paraphilic disorders (which additionally require the experience of distress or impairment in functioning).[1][2] Some paraphilias have more than one term to describe them, and some terms overlap with others. Paraphilias without DSM codes listed come under DSM 302.9, "Paraphilia NOS (Not Otherwise Specified)". In his 2008 book on sexual pathologies, Anil Aggrawal compiled a list of 547 terms describing paraphilic sexual interests. He cautioned, however, that "not all these paraphilias have necessarily been seen in clinical setups. This may not be because they do not exist, but because they are so innocuous they are never brought to the notice of clinicians or dismissed by them. Like allergies, sexual arousal may occur from anything under the sun, including the sun."[3] Most of the following names for paraphilias, constructed in the nineteenth and especially twentieth centuries from Greek and Latin roots (see List of medical roots, suffixes and prefixes), are used in medical contexts only. Contents A · B · C · D · E · F · G · H · I · J · K · L · M · N · O · P · Q · R · S · T · U · V · W · X · Y · Z Paraphilias A Paraphilia Focus of erotic interest Abasiophilia People with impaired mobility[4] Acrotomophilia -

2018 Juvenile Law Cover Pages.Pub

2018 JUVENILE LAW SEMINAR Juvenile Psychological and Risk Assessments: Common Themes in Juvenile Psychology THURSDAY MARCH 8, 2018 PRESENTED BY: TIME: 10:20 ‐ 11:30 a.m. Dr. Ed Connor Connor and Associates 34 Erlanger Road Erlanger, KY 41018 Phone: 859-341-5782 Oppositional Defiant Disorder Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Conduct Disorder Substance Abuse Disorders Disruptive Impulse Control Disorder Mood Disorders Research has found that screen exposure increases the probability of ADHD Several peer reviewed studies have linked internet usage to increased anxiety and depression Some of the most shocking research is that some kids can get psychotic like symptoms from gaming wherein the game blurs reality for the player Teenage shooters? Mylenation- Not yet complete in the frontal cortex, which compromises executive functioning thus inhibiting impulse control and rational thought Technology may stagnate frontal cortex development Delayed versus Instant Gratification Frustration Tolerance Several brain imaging studies have shown gray matter shrinkage or loss of tissue Gray Matter is defined by volume for Merriam-Webster as: neural tissue especially of the Internet/gam brain and spinal cord that contains nerve-cell bodies as ing addicts. well as nerve fibers and has a brownish-gray color During his ten years of clinical research Dr. Kardaras discovered while working with teenagers that they had found a new form of escape…a new drug so to speak…in immersive screens. For these kids the seductive and addictive pull of the screen has a stronger gravitational pull than real life experiences. (Excerpt from Dr. Kadaras book titled Glow Kids published August 2016) The fight or flight response in nature is brief because when the dog starts to chase you your heart races and your adrenaline surges…but as soon as the threat is gone your adrenaline levels decrease and your heart slows down. -

Sex and Disability

Sex and diSability Sex and diSability RobeRt McRueR and anna Mollow, editoRs duke univerSity PreSS duRhaM and london 201 2 © 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ♾ Designed by Nicole Hayward Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data and republication acknowledgments appear on the last printed page of this book. ContentS Acknowledgments / ix Introduction / 1 AnnA Mollow And RobeRt McRueR Part i: aCCeSS 1 A Sexual Culture for Disabled People / 37 tobin SiebeRS 2 Bridging Theory and Experience: A Critical- Interpretive Ethnography of Sexuality and Disability / 54 RuSSell ShuttlewoRth 3 The Sexualized Body of the Child: Parents and the Politics of “Voluntary” Sterilization of People Labeled Intellectually Disabled / 69 Michel deSjARdinS Part ii: HiStorieS 4 Dismembering the Lynch Mob: Intersecting Narratives of Disability, Race, and Sexual Menace / 89 Michelle jARMAn 5 “That Cruel Spectacle”: The Extraordinary Body Eroticized in Lucas Malet’s The History of Sir Richard Calmady / 108 RAchel o’connell 6 Pregnant Men: Modernism, Disability, and Biofuturity / 123 MichAel dAvidSon 7 Touching Histories: Personality, Disability, and Sex in the 1930s / 145 dAvid SeRlin Part iii: SPaCeS 8 Leading with Your Head: On the Borders of Disability, Sexuality, and the Nation / 165 nicole MARkotiĆ And RobeRt McRueR 9 Normate Sex and Its Discontents / 183 Abby l. wilkeRSon 10 I’m Not the Man I Used to Be: Sex, hiv, and Cultural “Responsibility” / 208 chRiS bell Part iv: liveS 11 Golem Girl Gets Lucky / 231 RivA lehReR 12 Fingered / 256 lezlie FRye 13 Sex as “Spock”: Autism, Sexuality, and Autobiographical Narrative / 263 RAchAel GRoneR Part v: deSireS 14 Is Sex Disability? Queer Theory and the Disability Drive / 285 AnnA Mollow 15 An Excess of Sex: Sex Addiction as Disability / 313 lennARd j. -

Introduction 1 Situating the Controlled Body 2 Bondage and Discipline, Dominance and Submission, and Sadomasochism (BDSM) At

Notes Introduction 1. In many respects, Blaine’s London feat is part of that shift. Whereas his entombment in ice in New York in 2000 prompted a media focus on his pun- ishing preparations (see Anonymous 2000, 17; Gordon 2000a, 11 and 2000b, 17), his time in the box brought much ridicule and various attempts to make the experience more intense, for instance a man beating a drum to deprive Blaine of sleep and a ‘flash mob’ tormenting him with hamburgers. 2. For some artists, pain is fundamental to the performance, but Franko B uses local anaesthetic, as he considers the end effect more important than the pain. 3. BDSM is regarded by many as less pejorative than sadomasochism; others choose S&M, S/M and SM. Throughout the book I retain each author’s appel- lation but see them fitting into the overarching concept of BDSM. 4. Within the BDSM scene there are specific distinctions and pairings of tops/ bottoms, Doms/subs and Masters/slaves, with increasing levels of control of the latter in each pairing by the former; for instance, a bottom will be the ‘receiver’ or takes the ‘passive’ part in a scene, whilst a sub will surrender control of part of their life to their Dominant. For the purposes of this book, I use the terms top and bottom (except when citing opinions of others) to suggest the respec- tive positions as I am mostly referring to broader notions of control. 5. Stressing its performative qualities, the term ‘scene’ is frequently used for the engagement in actual BDSM acts; others choose the term ‘play’, which as well as stressing its separation from the real has the advantage of indicating it is governed by predetermined rules. -

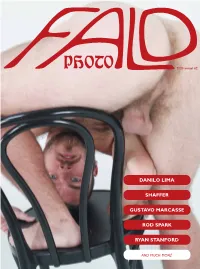

Ryan Stanford Danilo Lima Shaffer Rod

PHOTO 2020 annual #2 1 DANILO LIMA SHAFFER GUSTAVO MARCASSE ROD SPARK RYAN STANFORD AND MUCH MORE! 2 3 Eugenio by Rubaudanadeu, ECCE HOMO I series, digital collage in Hahnemühle photo Rag by Ramón Tormes, 2017. Guillermo Weickert, ECCE HOMO II series, digital collage in Hahnemühle photo Rag by Ramón Tormes, 2020. FALO ART© is a annual publication. january 2020. ISSN 2675-018X version 20.01.20 Summary editing, writing and design: Filipe Chagas editorial group: Dr. Alcemar Maia Souto, Guilherme Correa e Rigle Guimarães. Danilo Lima 6 cover: photo by Ryan Stanford. (model: Sebastian, 2020) Shaffer 20 others words, to understand our privileges, Care and technique were used in the edition of this magazine. Even so, typographical errors or conceptual Editorial our differences and similarities. We are not Gustavo Marcasse 38 doubt may occur. In any case, we request the alone. communication ([email protected]) so that we can ou have a very important verify, clarify or forward the question. magazine in your hands. To have their testimonials on a magazine Rod Spark 50 This horrible past year about photography was also very relevant. came with an agenda to Editor’s note on nudity: The five artists here work exactly with the Please note that publication is about the representation reconnect humankind, to Ryan Stanford diversity of the male body. More raw or 66 of masculinity in Art. There are therefore images of make us more solidary and empathic, to male nudes, including images of male genitalia. Please Y more artistic, colorful or monochromatic, make us leave our bubble of standards approach with caution if you feel you may be offended. -

Feminist Un/Pleasure: Reflections Upon Perversity, BDSM, and Desire Issue 2

feral feminisms Feminist Un/Pleasure: Reflections upon Perversity, BDSM, and Desire issue 2 . summer 2014 Feminist Un/Pleasure: Reflections upon Perversity, BDSM, and Desire E. Gravelet When you have only a handful of people who understand your way of life, their support becomes so important that no forgiveness for betrayal is even possible. Or so it would seem thus far. – Pat Califia 19 Every kinky feminist queer that I have ever spoken to loves Macho Sluts. Well, maybe I’m just lucky enough to know the right people, but there appears to be an overarching consensus that Patrick Califia’s hotly controversial 1988 collection of dyke S/M smut should be considered a classic. Not unlike the experience of many contemporary queer folks, it was one of the first pieces of BDSM literature I unearthed that actually resonated with my lived experiences and desires, and it subsequently spent many years living on my bedside table, creased open to “The Finishing School.” For a generation closely following Califia and his sex-positive peers, it might seem strange that this title would spur legal battles with the state or that its contents could contribute to the splintering of a thriving activist community. In 2000, however, Macho Sluts became a focal point in Little Sisters Book and Art Emporium v. Canada, the obscenity trials between Canada Customs and a small gay and lesbian bookstore situated in Vancouver, British Columbia. This collection of S/M erotica has had further impact on the infamous fragmentation at the heart of the feminist sex wars. Beginning in the late 1970s and continuing to this day, the North American second-wave feminist movement has been starkly divided by vehement political disagreements surrounding sexuality and gender. -

Sexual Deviance. Theory, Assessment, and Treatment. Second Edition

ANNALS OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY BOOKBOOK REVIEWS REVIEWS beginning of this review and provides SSexualexual DDeviance.eviance. TTheory,heory, a thoughtful critique of some issues. It starts by discussing defi nitional AAssessment,ssessment, aandnd TTreatment.reatment. matters and rightfully mentions that the DSM-IV-TR approach is an insti- SSecondecond eeditiondition tutional rather than scientifi c resolu- tion to the defi nition problem in this and other areas (as the authors note, SECOND EDITION of this encyclopedical volume— “there are no votes by the American both editors are psychologists and Chemical Association to determine there are only 4 MDs among the 50 whether oxygen or hydrogen is inside chapter authors. or outside this taxonomy” [p 1]). Th e The second, revised edition of authors and editors also are critical this book consists of 32 chapters. of development of treatments for The first 3 chapters—“Introduc- sexual deviations. Th ey say “we now tion,” “An integrated theory of sex- have a 50-year history of such treat- ual offending,” and “Sexual devi- ments, and it is entirely reasonable to ance over® Dowden the lifespan: reductions Health in Mediaask: What have we got to show for it? deviant sexual behavior in the aging Th e answer, sadly, is very little.” Th e sex off ender”—address some gen- authors state that we must do better Copyrighteral issues. All paraphilias, rape, and and suggest that we “ought to look Edited by D. Richard Laws and William T. For personal use only O’Donohue; The Guilford Press; New York, online sex off ending—including at a macro-organizational level and New York; 2008; ISBN 13: 978-1-59385- exhibitionism, fetishism, frotteur- plan strategies (as opposed to letting 605-2; pp 642; $70.00 (hardcover). -

Gender and SEXUALITY “DISORDERS” and Alexandre Baril and Kathryn Trevenen Sexuality University of Ottawa, Canada Abstract

Annual Review EXPLORING ABLEISM AND of Critical Psychology 11, 2014 CISNORMATIVITY IN THE CONCEPTUALIZATION OF IDENTITY Gender AND SEXUALITY “DISORDERS” and Alexandre Baril and Kathryn Trevenen Sexuality University of Ottawa, Canada Abstract This article explores different conceptualizations of, and debates about, Body Integrity Identity Disorder and Gender Identity Disorder to first examine how these “identity disorders” have been both linked to and distinguished from, the “sexual disorders” of apotemnophilia (the de- sire to amputate healthy limbs) and autogynephilia (the desire to per- ceive oneself as a woman). We argue that distinctions between identity disorders and sexual disorders or paraphilias reflect a troubling hier- archy in medical, social and political discourses between “legitimate” desires to transition or modify bodies (those based in identity claims) and “illegitimate” desires (those based in sexual desire or sexuality). This article secondly and more broadly explores how this hierarchy between “identity troubles” and paraphilias is rooted in a sex-negative, ableist, and cisnormative society, that makes it extremely difficult for activists, individuals, medical professionals, ethicists and anyone else, to conceptualize or understand the desires that some people express around transforming their bodies—whether the transformation relates to sex, gender or ability. We argue that instead of seeking to “explain” these desires in ways that further pathologize the people articulating them, we need to challenge the ableism and cisnormativity that require explanations for some bodies, subjectivities and desires while leaving dominant normative bodies and subjectivities intact. We thus end the article by exploring possibilities for forging connections between trans studies and critical disability studies that would open up options for listening and responding to the claims of transabled people.