Current Situation of Residents in Tigray Region Brief Monitoring Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Food Supply Prospects - 2009

FOOD SUPPLY PROSPECTS - 2009 Disaster Management and Food Security Sector (DMFSS) Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MoARD) Addis Ababa Ethiopia February 10, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages LIST OF GLOSSARY OF LOCAL NAMES 2 ACRONYMS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 - 8 INTRODUCTION 9 - 12 REGIONAL SUMMARY 1. SOMALI 13 - 17 2. AMHARA 18 – 22 3. SNNPR 23 – 28 4. OROMIYA 29 – 32 5. TIGRAY 33 – 36 6. AFAR 37 – 40 7. BENSHANGUL GUMUZ 41 – 42 8. GAMBELLA 43 - 44 9. DIRE DAWA ADMINISTRATIVE COUNSEL 44 – 46 10. HARARI 47 - 48 ANNEX – 1 NEEDY POPULATION AND FOOD REQUIREMENT BY WOREDA 2 Glossary Azmera Rains from early March to early June (Tigray) Belg Short rainy season from February/March to June/July (National) Birkads cemented water reservoir Chat Mildly narcotic shrub grown as cash crop Dega Highlands (altitude>2500 meters) Deyr Short rains from October to November (Somali Region) Ellas Traditional deep wells Enset False Banana Plant Gena Belg season during February to May (Borena and Guji zones) Gu Main rains from March to June ( Somali Region) Haga Dry season from mid July to end of September (Southern zone of of Somali ) Hagaya Short rains from October to November (Borena/Bale) Jilal Long dry season from January to March ( Somali Region) Karan Rains from mid-July to September in the Northern zones of Somali region ( Jijiga and Shinile zones) Karma Main rains fro July to September (Afar) Kolla Lowlands (altitude <1500meters) Meher/Kiremt Main rainy season from June to September in crop dependent areas Sugum Short rains ( not more than 5 days -

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

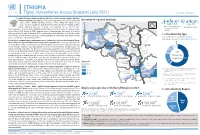

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008)

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008) ma, maa (O) why? HES37 Ma 1258'/3813' 2093 m, near Deresge 12/38 [Gz] HES37 Ma Abo (church) 1259'/3812' 2549 m 12/38 [Gz] JEH61 Maabai (plain) 12/40 [WO] HEM61 Maaga (Maago), see Mahago HEU35 Maago 2354 m 12/39 [LM WO] HEU71 Maajeraro (Ma'ajeraro) 1320'/3931' 2345 m, 13/39 [Gz] south of Mekele -- Maale language, an Omotic language spoken in the Bako-Gazer district -- Maale people, living at some distance to the north-west of the Konso HCC.. Maale (area), east of Jinka 05/36 [x] ?? Maana, east of Ankar in the north-west 12/37? [n] JEJ40 Maandita (area) 12/41 [WO] HFF31 Maaquddi, see Meakudi maar (T) honey HFC45 Maar (Amba Maar) 1401'/3706' 1151 m 14/37 [Gz] HEU62 Maara 1314'/3935' 1940 m 13/39 [Gu Gz] JEJ42 Maaru (area) 12/41 [WO] maass..: masara (O) castle, temple JEJ52 Maassarra (area) 12/41 [WO] Ma.., see also Me.. -- Mabaan (Burun), name of a small ethnic group, numbering 3,026 at one census, but about 23 only according to the 1994 census maber (Gurage) monthly Christian gathering where there is an orthodox church HET52 Maber 1312'/3838' 1996 m 13/38 [WO Gz] mabera: mabara (O) religious organization of a group of men or women JEC50 Mabera (area), cf Mebera 11/41 [WO] mabil: mebil (mäbil) (A) food, eatables -- Mabil, Mavil, name of a Mecha Oromo tribe HDR42 Mabil, see Koli, cf Mebel JEP96 Mabra 1330'/4116' 126 m, 13/41 [WO Gz] near the border of Eritrea, cf Mebera HEU91 Macalle, see Mekele JDK54 Macanis, see Makanissa HDM12 Macaniso, see Makaniso HES69 Macanna, see Makanna, and also Mekane Birhan HFF64 Macargot, see Makargot JER02 Macarra, see Makarra HES50 Macatat, see Makatat HDH78 Maccanissa, see Makanisa HDE04 Macchi, se Meki HFF02 Macden, see May Mekden (with sub-post office) macha (O) 1. -

Productive and Reproductive Performance of Local Cows Under Farmer’S Management in Central Tigray, Ethiopia

Nigerian J. Anim. Sci. 2020 Vol 22 (3): 70-74 (ISSN:1119-4308) © 2020 Animal Science Association of Nigeria (https://www.ajol.info/index.php/tjas) available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Productive and reproductive performance of local cows under farmer’s management in central Tigray, Ethiopia Abrha B. H., Niraj K.*, Berihu G., Kiros A. and Gebregiorgis A. G. College of Veterinary Medicine, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Ethiopia *Corresponding Author: [email protected] (Mob: +251.966675736) Target audience: Ministry of Agriculture, Researchers, Dairy Policy Makers Abstract The study was conducted on 408 indigenous cows maintained under farmer’s management in eight districts of central Tigray, Ethiopia. A total of 208 small-scale dairy farm owners were randomly selected and interviewed with structured questionnaire to obtain information on the productive and reproductive performance of indigenous cows. The results of the study showed that the mean age at first calving (AFC) was 43.3 ±2.7 months, number of services per conception (NSC) was 2.7±0.5, days open (DO) was 201.47±61.21 days, calving interval (CI) was 468.33±71.42 days, lactation length (LL) was 206.17±32.33 days, lactation milk yield (LMY) was 414.65±53.69 litres for indigenous cows. The estimated value for productive and reproductive traits had higher than normal range in indigenous cows. This calls for a planned technical and institutional intervention for improved support services for appropriate breeding programs, improved cows and adequate veterinary health services. Key words: Productive and Reproductive Performance, Local Cows. -

St Justin De Jacobis: Founder of the New Catholic Generation and Formator of Its Native Clergy in the Catholic Church of Eritrea and Ethiopia

Vincentiana Volume 44 Number 6 Vol. 44, No. 6 Article 6 11-2000 St Justin de Jacobis: Founder of the New Catholic Generation and Formator of its Native Clergy in the Catholic Church of Eritrea and Ethiopia Abba lyob Ghebresellasie C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ghebresellasie, Abba lyob C.M. (2000) "St Justin de Jacobis: Founder of the New Catholic Generation and Formator of its Native Clergy in the Catholic Church of Eritrea and Ethiopia," Vincentiana: Vol. 44 : No. 6 , Article 6. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol44/iss6/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. St Justin de Jacobis: Founder of the New Catholic Generation and Formator of its Native Clergy in the Catholic Church of Eritrea and Ethiopia by Abba lyob Ghebresellasie, C.M. Province of Eritrea Introduction Biblical References to the Introduction of Christianity in the Two Countries While historians and archeologists still search for hard evidence of early Christian settlements near the western shore of the Red Sea, it is not difficult to find biblical references to the arrival of Christianity in our area. And behold an Ethiopian, eunuch, a minister of Candace, queen of Ethiopia, who was in charge of all her treasurers, had come to Jerusalem to worship... -

United Nations Country Team Ethiopia

UNITED NATIONS COUNTRY TEAM ETHIOPIA HUMANITARIAN NEEDS OF WAR DISPLACED AND DROUGHT AFFECTED PEOPLE IN TIGRAY United Nations Country Team Rapid Assessment Mission 7-8 April 1999 HUMANITARIAN NEEDS OF WAR DISPLACED AND DROUGHT AFFECTED PEOPLE IN TIGRAY United Nations Country Team Rapid Assessment Mission 7-8 April 1999 SUMMARY OF KEY POINTS § Members of the UN Country Team, together with the DPPC Commissioner and representatives of the regional administration, visited Mekelle, Adigrat, Axum and Shire to assess the condition of the war displaced and drought affected in Tigray. § Currently, the total number of internally displaced in Tigray stands at 315,936 with an additional 14,762 officially registered Ethiopians who have returned to Tigray from Eritrea since the start of the war. Compounding the problem of assisting these people is the condition of localized drought, estimated to be affecting 373,013 additional people in the region. § Most of the displaced are integrated into local communities, although some camp-like settlements have had to be established in view of the large numbers of displaced as compared to hosts. § Priority needs include food, shelter materials, blankets, water, sanitation, education and health facilities in areas hosting the displaced. § Proliferation of landmines in the conflict areas prevents the safe return of many of the displaced. Rehabilitation of destroyed or damaged infrastructure will also eventually be necessary to facilitate return. § Donors and other interested partners are encouraged to evaluate the general needs identified herein in making additional contributions and expediting delivery of relief and rehabilitation assistance to the affected areas. Mission Objectives This mission to Tigray Region, Ethiopia, was undertaken at the request of the UN Resident Coordinator in order to gain a preliminary indication of the current humanitarian situation due to the renewed fighting and the localized drought conditions that Tigray is reported to be currently facing. -

ETHIOPIA - TIGRAY REGION HUMANITARIAN UPDATE Situation in Tigray (1 July 2021) Last Updated: 2 Jul 2021

ETHIOPIA - TIGRAY REGION HUMANITARIAN UPDATE Situation in Tigray (1 July 2021) Last updated: 2 Jul 2021 FLASH UPDATE (2 Jul 2021) Situation in Tigray (1 July 2021) The political dynamics have changed dramatically in Ethiopia's Tigray Region following the unilateral ceasefire declaration by the Ethiopian Government on 28 June 2021. Reportedly, the Tigray Defense Forces (TDF) have taken control over most parts of Tigray following the withdrawal of the Ethiopian and Eritrean defense forces from the capital, Mekelle, and other parts of the region, while Western Tigray remains under the control of the Amhara Region. The consequences of the unfolding situation on humanitarian operations in Tigray remain fluid. The breakdown of essential services such as the blackout of electricity, telecommunications, and internet throughout Tigray region will only exacerbate the already dire humanitarian situation. Reported shortages of cash and fuel in the region can compromise the duty of care of aid workers on the ground. Despite the dynamic and uncertain situation, partners report that the security situation in Tigray has been generally calm over the past few days, with limited humanitarian activities being implemented around Mekelle and Shire. Key developments On 28 June, the Federal Government agreed to the request from the Interim Regional Administration in Tigray for a "unilateral ceasefire, until the farming season ends." Subsequently, Ethiopia National Defense Forces (ENDF) withdrew from Mekelle and other main towns in the region, including Shire, Axum, Adwa, and Adigrat. Currently, former Tigray Defense Forces (TDF) are in control of the main cities and roads in Tigray. There were no reports of fighting in Mekelle and other towns. -

Factors Affecting Choice of Place for Childbirth Among Women's in Ahferom Woreda, Tigray, 2013

Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences (SJAMS) ISSN 2320-6691 (Online) Sch. J. App. Med. Sci., 2014; 2(2D):830-839 ISSN 2347-954X (Print) ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publisher (An International Publisher for Academic and Scientific Resources) www.saspublisher.com Research Article Factors Affecting Choice of Place for Childbirth among Women’s in Ahferom Woreda, Tigray, 2013 Haftom Gebrehiwot Department of Midwifery, College of Health Sciences, Mekelle University, Ethiopia *Corresponding author Haftom Gebrehiwot Email: Abstract: Reduction of maternal mortality is a global priority. The key to reducing maternal mortality ratio is increasing attendance by skilled health personnel throughout pregnancy and delivery. However, delivery service is significantly lower in Tigray region. Therefore, this study aimed to assess factors affecting choice of place of child birth among women in Ahferom woreda. A community based cross-sectional study both quantitative and qualitative method was employed among 458 women of age 15-49 years that experienced child birth and pregnancy in Ahferom woreda, Ethiopia. Multi stage stratified sampling technique with Probabilities proportional to size was used to select the study subjects for quantitative and focus group discussions (FGDs) for the qualitative survey. Study subjects again were selected by systematic random sampling technique from randomly selected kebelle’s in the Woreda. Data was collected using structured interview questionnaire and analyzed using SPPS version 16.0. A total of 458 women participated in the quantitative survey. One third of women were age 35 and above, 118(25.8%) were aged between 25-29 years. 247(53.9%) of women were illiterate, and 58.7% of women choice home as place of birth and 41.3% choice health facilities. -

D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 1

D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 1. Tigrey No. Woredas Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Expected Connecting Point 1 Adwa 13 Per Filed Survey by ETC 2(*) Hawzen 12 3(*) Wukro 7 Per Feasibility Study 4(*) Samre 13 Per Filed Survey by ETC 5 Alamata 10 Total 55 1 Tahtay Adiyabo 8 2 Medebay Zana 10 3 Laelay Mayechew 10 4 Kola Temben 11 5 Abergele 7 Per Filed Survey by ETC 6 Ganta Afeshum 15 7 Atsbi Wenberta 9 8 Enderta 14 9(*) Hintalo Wajirat 16 10 Ofla 15 Total 115 1 Kafta Humer 5 2 Laelay Adiyabo 8 3 Tahtay Koraro 8 4 Asegede Tsimbela 10 5 Tselemti 7 6(**) Welkait 7 7(**) Tsegede 6 8 Mereb Lehe 10 9(*) Enticho 21 10(**) Werie Lehe 16 Per Filed Survey by ETC 11 Tahtay Maychew 8 12(*)(**) Naeder Adet 9 13 Degua temben 9 14 Gulomahda 11 15 Erob 10 16 Saesi Tsaedaemba 14 17 Alage 13 18 Endmehoni 9 19(**) Rayaazebo 12 20 Ahferom 15 Total 208 1/14 Tigrey D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 2. Affar No. Woredas Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Expected Connecting Point 1 Ayisaita 3 2 Dubti 5 Per Filed Survey by ETC 3 Chifra 2 Total 10 1(*) Mile 1 2(*) Elidar 1 3 Koneba 4 4 Berahle 4 Per Filed Survey by ETC 5 Amibara 5 6 Gewane 1 7 Ewa 1 8 Dewele 1 Total 18 1 Ere Bti 1 2 Abala 2 3 Megale 1 4 Dalul 4 5 Afdera 1 6 Awash Fentale 3 7 Dulecha 1 8 Bure Mudaytu 1 Per Filed Survey by ETC 9 Arboba Special Woreda 1 10 Aura 1 11 Teru 1 12 Yalo 1 13 Gulina 1 14 Telalak 1 15 Simurobi 1 Total 21 2/14 Affar D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 3. -

Addis Ababa University, College of Health Sciences, School of Public Health

Addis Ababa University College of Health Science School of Public Health Addis Ababa University, College of Health Sciences, School of Public Health Ethiopia Field pidemiology Training Program (EFETP) Compiled Body of Works in Field Epidemiology By Addisalem Mesfin Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Public Health in Field Epidemiology May, 2016 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Cell phone: 0911243303 E-mail: [email protected] AAU/SPH/AM Addis Ababa University College of Health Science School of Public Health Addis Ababa University, College of Health Sciences, School of Public Health Ethiopia Field Epidemiology Training Program (EFETP) Compiled Body of Works in Field Epidemiology By Addisalem Mesfin Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Public Health in Field Epidemiology Advisors 1. Dr. Daddi Jimma 2. Dr. Alemayehu Bekele May 2016 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia AAU/SPH/AM Addis Ababa University College of Health Science School of Public Health ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies Compiled Body of Works in Field Epidemiology By Addisalem Mesfin May 2016 Ethiopia Field Epidemiology Training Programme (EFETP) School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences Addis Ababa University Approved by Examining ____________________ _______________________ Chairman, School Graduate Committee _______________________________ ___________________________ Advisor ______________________ _____________________