Interdisciplinary Dimensions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April Wine Greatest Hits Mp3, Flac, Wma

April Wine Greatest Hits mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Greatest Hits Country: Canada Released: 1979 Style: Hard Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1878 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1129 mb WMA version RAR size: 1165 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 917 Other Formats: VOC WMA DTS AC3 DMF VOX TTA Tracklist Hide Credits Fast Train A1 2:39 Written-By – M. Goodwyn* Drop Your Guns A2 3:31 Written-By – D. Henman* Weeping Widow A3 3:53 Written-By – R. Wright* Rock N' Roll Is A Vicious Game A4 3:22 Written-By – M. Goodwyn* Oowatanite A5 3:35 Written-By – J. Clench* You Could Have Been A Lady A6 3:20 Written-By – E. Brown*, T. Wilson* Roller A7 3:34 Written-By – M. Goodwyn* Like A Lover, Like A Song B1 3:46 Written-By – M. Goodwyn* I'm On Fire For You Baby B2 3:29 Written-By – D. Elliott* Lady Run, Lady Hide B3 2:57 Written-By – J. Clench*, M. Goodwyn* Bad Side Of The Moon B4 3:12 Written-By – E. John-B, Taupin* I Wouldn't Want To Lose Your Love B5 3:07 Written-By – M. Goodwyn* You Won't Dance With Me B6 3:42 Written-By – M. Goodwyn* Tonite Is A Wonderful Time To Fall In Love B7 3:18 Written-By – M. Goodwyn* Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Aquarius Records Ltd. Pressed By – Capitol Records-EMI Of Canada Limited Mastered At – Disques SNB Ltée. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Aquarius Records Credits Producer – Bill Hill Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout Side A, [Etched]): AQR-525-A- (Target logo) TLC-A Matrix / Runout (Runout Side B, [Etched]): AQR-525-B3 REZ TLC-T Matrix / Runout (Runout, Both Sides, [Stamped]): "Target" -

Once There Was Nothing, a Great Chaos of Nothing. Then There Was Order

"Once there was nothing, a great chaos of nothing. Then there was order. Order came from the nothing and created the materium, the physical world, and in its quest for control, it created disparity, and from disparity came corruption, and the immaterium, the non-physical worlds beyond the event horizon. The two battled, and broke upon each other for an age, forging weapons of immense size and power across the voids of materium and imamaterium. Then there was the Third, and the Third was given the first choice, continue along the path of broken futility, or descend, and at the cost of oblivion become more. Then there was more, then there was life. The first life broke and shattered at the cost of the Third and the first death, but then came more, and life spread to all corners of existence, to even the depths of space, the children of the Third. Order fell first, and broke, leaving its scattered ashes across life, giving them the desire for more, faith in something greater and all the pain it causes. Corruption fell slower, and broke into shards, gods in between the cracks of oblivion, some intent upon seizing the forming existence, others content to await the day their time would come, as all that is, is doomed to break and die. This was the inception of our existence, of which our small universe is only a very small part of. Before this universe there was another, in which the bastards of corruption attempted to force entry into this reality at the heat death of the universe, to become consumers of the next one after, they built cults and bade them to work in the places they could not reach, and readied their entrance, what they did not suspect that the little monsters that had infested this existence had the gall to oppose them. -

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 32.95 21.95 20.95 26.95 26.95

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 10" 13th Floor Elevators You`re Gonna Miss Me (pic disc) 803415820412 32.95 10" A Perfect Circle Doomed/Disillusioned 4050538363975 21.95 10" A.F.I. All Hallow's Eve (Orange Vinyl) 888072367173 20.95 10" African Head Charge 2016RSD - Super Mystic Brakes 5060263721505 26.95 10" Allah-Las Covers #1 (Ltd) 184923124217 26.95 10" Andrew Jackson Jihad Only God Can Judge Me (white vinyl) 612851017214 24.95 10" Animals 2016RSD - Animal Tracks 018771849919 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Are Back 018771893417 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Is Here (EP) 018771893516 21.95 10" Beach Boys Surfin' Safari 5099997931119 26.95 10" Belly 2018RSD - Feel 888608668293 21.95 10" Black Flag Jealous Again (EP) 018861090719 26.95 10" Black Flag Six Pack 018861092010 26.95 10" Black Lips This Sick Beat 616892522843 26.95 10" Black Moth Super Rainbow Drippers n/a 20.95 10" Blitzen Trapper 2018RSD - Kids Album! 616948913199 32.95 10" Blossoms 2017RSD - Unplugged At Festival No. 6 602557297607 31.95 (45rpm) 10" Bon Jovi Live 2 (pic disc) 602537994205 26.95 10" Bouncing Souls Complete Control Recording Sessions 603967144314 17.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Dropping Bombs On the Sun (UFO 5055869542852 26.95 Paycheck) 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Groove Is In the Heart 5055869507837 28.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Mini Album Thingy Wingy (2x10") 5055869507585 47.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre The Sun Ship 5055869507783 20.95 10" Bugg, Jake Messed Up Kids 602537784158 22.95 10" Burial Rodent 5055869558495 22.95 10" Burial Subtemple / Beachfires 5055300386793 21.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician 868798000332 22.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician (Red 868798000325 29.95 Vinyl/Indie-retail-only) 10" Cisneros, Al Ark Procession/Jericho 781484055815 22.95 10" Civil Wars Between The Bars EP 888837937276 19.95 10" Clark, Gary Jr. -

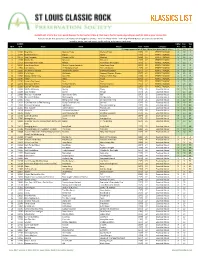

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT -

Highlander V0.7 (Maybe Now I Won't Have to Tear My Eyes Out, Edition)

Traveller's Tale By: Highlander V0.7 (Maybe now I won't have to tear my eyes out, Edition) "Once there was nothing, a great chaos of nothing. Then there was order. Order came from the nothing and created the materium, the physical world, and in its quest for control, it created disparity, and from disparity came corruption, and the immaterium, the non-physical worlds beyond the event horizon. The two battled, and broke upon each other for an age, forging weapons of immense size and power across the voids of materium and imamaterium. Then there was the Third, and the Third was given the first choice, continue along the path of broken futility, or descend, and at the cost of oblivion become more. Then there was more, then there was life. The first life broke and shattered at the cost of the Third and the first death, but then came more, and life spread to all corners of existence, to even the depths of space, the children of the Third. Order fell first, and broke, leaving it’s scattered ashes across life, giving them the desire for more, faith in something greater and all the pain it causes. Corruption fell slower, and broke into shards, gods in between the cracks of oblivion, some intent upon seizing the forming existence, others content to await the day their time would come, as all that is, is doomed to break and die. This was the inception of our existence, of which our small universe is only a very small part of. Before this universe there was another, in which the bastards of corruption attempted to force entry into this reality at the heat death of the universe, to become consumers of the next one after, they built cults and bade them to work in the places they could not reach, and readied their entrance, what they did not suspect that the little monsters that had infested this existence had the gall to oppose them. -

The Meaning of Life According to Lev Tolstoy and Emile Zola

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Pessimism, Religion, and the Individual in History: The Meaning of Life According to Lev Tolstoy and Émile Zola Francis Miller Pfost Jr. Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES PESSIMISM, RELIGION, AND THE INDIVIDUAL IN HISTORY: THE MEANING OF LIFE ACCORDING TO LEV TOLSTOY AND ÉMILE ZOLA By FRANCIS MILLER PFOST JR. A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Modern Languages and Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2005 Copyright ©2005 Francis Miller Pfost Jr. All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Francis Miller Pfost, Jr. defended on 3 November 2005. Antoine Spacagna Professor Directing Dissertation David Kirby Outside Committee Member Joe Allaire Committee Member Nina Efimov Committee Member Approved: William J. Cloonan, Chair, Department of Modern Languages and Linguistics Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my parents, Francis Miller Pfost and Mary Jane Channell Pfost, whose love and support made this effort possible iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract v INTRODUCTION 1 PART ONE: LEV TOLSTOY AND THE SPIRITUAL APPROACH INTRODUCTION 2 1. EARLY IMPRESSIONS AND WRITINGS TO 1851 3 2. THE MILITARY PERIOD 1851-1856 17 3. DEATHS, FOREIGN TRIPS, AND MARRIAGE: THE PRELUDE TO WAR AND PEACE 1856-1863 49 4. -

April Wine All the Rockers Mp3, Flac, Wma

April Wine All The Rockers mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: All The Rockers Country: Canada Released: 1987 Style: Hard Rock, Arena Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1592 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1183 mb WMA version RAR size: 1361 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 286 Other Formats: ASF MP4 VOC MOD XM DTS AHX Tracklist A1 Anything You Want, You Got It A2 I Like To Rock A3 Roller A4 All Over Town A5 Hot On The Wheels Of Love A6 Tonite A7 Future Tense A8 21st Century Schizoid Man B1 Crash & Burn B2 Oowatanite B3 Don't Push Me Around B4 Get Ready For Love B5 Tellin' Me Lies B6 Blood Money B7 Gimme Love B8 Weeping Widow B9 Victim For Your Love Notes Columbia House Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year All The Rockers (CD, Aquarius Q2 550 April Wine Q2 550 Canada 1987 Comp) Records Q2 550 The Rockers (CD, Aquarius Q2 550 April Wine Canada 1987 PROMO Comp, Promo) Records PROMO All The Rockers (CD, Aquarius AQCD 550 April Wine AQCD 550 Canada Unknown Comp) Records All The Rockers Aquarius 4AQ 550 April Wine 4AQ 550 Canada 1987 (Cass, Comp) Records Related Music albums to All The Rockers by April Wine Rock April Wine - The Hits Rock April Wine - Animal Grace Rock April Wine - Live On The King Biscuit Flower Hour Rock April Wine - Walking Through Fire Rock April Wine - Oowatanite Rock April Wine - Power Play Rock April Wine - Rock N' Roll Is A Vicious Game Rock April Wine - Roller Rock April Wine - Stand Back Rock April Wine - First Glance. -

April Wine I Like to Rock: Live in London 1981

April Wine I Like To Rock: Live In London 1981 Their first ever DVD! Classic archive material from London's Hammersmith Odeon during the band's 1981 tour of the UK. This DVD contains a complete and incredible concert performed at London's Hammersmith Odeon during the band's 1981 tour of the UK. They formed in late 1969 in Halifax, Nova Scotia and their first hit, "Fast Train," appeared in 1971, the same year as the self-titled debut album. The next year brought the band's first Canadian number one single, "You Could Have Been a Lady," from the On Record album. In 1976, The Whole World's Goin' Crazy became the first Canadian album to go platinum and their resulting tour was the first to gross one million dollars. After 1978's First Glance and 1979's Harder... Faster, 'Just Between You and Me' became April Wine's biggest U.S. hit. The single (one of three Top 40 American singles by the band) propelled 1981's Nature of the Beast album to platinum-record status. 1984's Animal Grace was their last album, but in the early 1990's all the original members joined for a Canadian tour, which convinced them to resume recording, they are still recording and touring the world to their ever-loyal fan-base. TRACK LISTING • Big City Girls • Crash And Burn • Telling Me Lies • Future Tense • Ladies Man • Crossfire • Gypsy Queen Artist April Wine • Between You And Me Title I Like To Rock: Live In London 1981 Selection # CRDVD168 • Bad Toys UPC 5013929936850 • One More Time Prebook 5/6/2008 21st Century Man Street Date 6/10/2008 • Retail $19.95 • Roller Genre Pop/Rock I Like To Rock Run Time 66 mins • Box Lot 30 • 27 Label CHERRY RED • All Over Town Audio Stereo Format DVD • I Want To Rock 800.888.0486 F 610.650.9102 PO Box 280, Oaks, PA 19456 www.MVDb2b.com Publicity: Clint Weiler 610.650.8200 x115 [email protected]. -

2 .)C.3-T?- Undergrads Claim Unfairness in Bioengineering Plans

-frff :2 .)C.3-T?- Undergrads claim unfairness in bioengineering plans by David Schnur public. "There isn't a real Clark stated that staff shortages, Acting Department Chairman about her opinion of the The Department of Electrical mechanism to make that though, were the prime reason Sid Burrus was out of town and elimination. "We've been shafted and Computer Engineering has announcement. Students will be behind the closing. "We used to unavailable for comment. The department never let me decided to phase out its told when they go to register next have three professors here. Now Underclassmen who hoped to know. The course listings came out undergraduate concentration in month," he said. I'm the only one. 1 have eight concentrate in bioengineering are for next year and the bioengineer- Bioengineering beginning this fall. Bioengineering professor John graduate students in this area, and upset that they were never notified ing courses simply aren't there," The department apparently Clark commented, "Until they I can't teach so many of the elimination of the program. she said. chose several weeks ago to close declare a major, sophomores are undergraduate courses," he noted. Said Lovett College freshman Stanford explained what her the concentration to freshmen and not actually members of the The department has tried but Gaurav Cioel, "1 don't think there alternatives are. "The suggestion sophomores, but failed to make an department. It's a department has not been able to get has been any official word. 1 found from the EE department is to official announcement. Juniors decision and it's unfair to some, replacements for the professors out from my suitemate one night a concentrate in Circuits and and seniors who are currently but there are quite a few courses who left. -

Occulture Boris+Davis+Techgnosis

A PAPERBACK ORIGINAL 'TechGnosi$ is a wonderfully written investigation of the dreams, hopes and fears we project onto technology. As comfortable with ancient gnostic lore as he is with modern day net politics, Erik Davis grounds his theoretical speculations in rigorous reporting ... a dazzling performance.' Jim McClellan 'A most informative account of a culture %yhose secular concerns continue to collide with their supei'natural Ifyprsi Sadie Plant, VLS \ \ From the printing press to the telegraph, through radio, TV and the Internet, TechGnosis explores the mystical impulses that lie behind our obsession with information technology. In this thrilling book, writer and cyber guru Erik Davis demonstrates how religious imagination, magical dreams and millennialist fervour have always permeated the story of technology. Through shamanism to gnosticism, voodoo to alchemy. Buddhism to evangelism, TechGnosis peels away the rational shell of info tech to reveal the utopian dreams, alien obsessions and apocalyptic visions that populate the ongoing digital revolution. Erik Davis offers a unique and fascinating perspective on technoculture, inviting comparisons to Marshall McLuhan, Greil Marcus and William Gibson. Lucid and hip, TechGnosis is a journey into the next millennium's hyper-mediated environment, whose morphing boundaries and terminal speed are reshaping our very identities. ISBN 1-85242-645-4 Cover by Stanley Donwood Cultural Studies/Popular Science/Philosophy £14.99 Serpent's Tail 852 426453 Erik Davis is a fifth-generation Californian who currently resides in San Francisco. His work has appeared in Wired, The Village Voice, Gnosis, and other publications, and he has lectured internationally on techno culture and the fringes of religion. -

9780313348006.Pdf

Encyclopedia of Heavy Metal Music This page intentionally left blank Encyclopedia of Heavy Metal Music WILLIAM PHILLIPS AND BRIAN COGAN GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut x London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Phillips, William, 1961– Encyclopedia of heavy metal music / William Phillips and Brian Cogan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-34800-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heavy metal (Music)—Encyclopedias. 2. Heavy metal (Music)—Bio-bibliography— Dictionaries. I. Cogan, Brian, 1967– II. Title. ML102.R6P54 2009 781.66—dc22 2008034199 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2009 by William Phillips and Brian Cogan All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008034199 ISBN: 978-0-313-34800-6 First published in 2009 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48-1984). 10987654321 Contents List of Entries vii Guide to Related Topics xiii Preface xix Acknowledgments xxiii The Encyclopedia 1 Heavy Metal Music: An Introduction 3 Entries A–Z 10 Selected Bibliography 271 Index 275 This page intentionally left blank List of Entries Accept Bad News AC/DC Bang Tango Aerosmith Bathory Agalloch Beatallica Airheads Behemoth Alabama Thunder Pussy Biohazard Alcatrazz Black Label Society Alcohol Black Metal Alice Cooper Black Sabbath Alice in Chains Blitzkreig The Amboy Dukes Bloodstock Amon Amarth Blue Cheer Amps Blue Murder € Anaal Nathrakh Blue Oyster Cult Angel Witch Body Count Anthrax Tommy Bolin Anvil Bolt Thrower April Wine Bon Jovi Arch Enemy Boris Armored Saint Britny Fox Asphalt Ballet Buckcherry At the Gates Budgie Autograph Bullet Boys Avenged Sevenfold Burning Witch Badlands William S. -

"Rock Against Reagan": the Punk Movement, Cultural Hegemony, and Reaganism in the Eighties

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2016 "Rock against Reagan": The punk movement, cultural hegemony, and Reaganism in the eighties Johnathan Kyle Williams University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2016 Johnathan Kyle Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Johnathan Kyle, ""Rock against Reagan": The punk movement, cultural hegemony, and Reaganism in the eighties" (2016). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 239. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/239 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by JOHNATHAN KYLE WILLIAMS 2015 All Rights Reserved “ROCK AGAINST REAGAN”: THE PUNK MOVEMENT, CULTURAL HEGEMONY, AND REAGANISM IN THE EIGHTIES An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Johnathan Kyle Williams University of Northern Iowa May, 2016 ABSTRACT Despite scholars’ growing interest in the cultural movement known as punk, there has been a lack of focus on the movement’s relationship to its historical context. Punk meant rebellion, and this research looks at how the rebellion of the American punk movement during the eighties [1978 to 1992], was aimed at the president Ronald Reagan. Their dissent, however, was not only directed towards Reagan, but the culture that he encompassed.