Bolan, Bowie and the Carnivalesque

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Sunfly (All) Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Comic Relief) Vanessa Jenkins & Bryn West & Sir Tom Jones & 3OH!3 Robin Gibb Don't Trust Me SFKK033-10 (Barry) Islands In The Stream SF278-16 3OH!3 & Katy Perry £1 Fish Man Starstrukk SF286-11 One Pound Fish SF12476 Starstrukk SFKK038-10 10cc 3OH!3 & Kesha Dreadlock Holiday SF023-12 My First Kiss SFKK046-03 Dreadlock Holiday SFHT004-12 3SL I'm Mandy SF079-03 Take It Easy SF191-09 I'm Not In Love SF001-09 3T I'm Not In Love SFD701-6-05 Anything FLY032-07 Rubber Bullets SF071-01 Anything SF049-02 Things We Do For Love, The SFMW832-11 3T & Michael Jackson Wall Street Shuffle SFMW814-01 Why SF080-11 1910 Fruitgum Company 3T (Wvocal) Simon Says SF028-10 Anything FLY032-15 Simon Says SFG047-10 4 Non Blondes 1927 What's Up SF005-08 Compulsory Hero SFDU03-03 What's Up SFD901-3-14 Compulsory Hero SFHH02-05-10 What's Up SFHH02-09-15 If I Could SFDU09-11 What's Up SFHT006-04 That's When I Think Of You SFID009-04 411, The 1975, The Dumb SF221-12 Chocolate SF326-13 On My Knees SF219-04 City, The SF329-16 Teardrops SF225-06 Love Me SF358-13 5 Seconds Of Summer Robbers SF341-12 Amnesia SF342-12 Somebody Else SF367-13 Don't Stop SF340-17 Sound, The SF361-08 Girls Talk Boys SF366-16 TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME SF390-09 Good Girls SF345-07 UGH SF360-09 She Looks So Perfect SF338-05 2 Eivissa She's Kinda Hot SF355-04 Oh La La La SF114-10 Youngblood SF388-08 2 Unlimited 50 Cent No Limit FLY027-05 Candy Shop SF230-10 No Limit SF006-05 Candy Shop SFKK002-09 No Limit SFD901-3-11 In Da -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

Heroes Magazine

HEROES ISSUE #01 Radrennbahn Weissensee a year later. The title of triumphant, words the song is a reference to the 1975 track “Hero” by and music. Producer Tony Visconti took credit for the German band Neu!, whom Bowie and Eno inspiring the image of the lovers kissing “by the admired. It was one of the early tracks recorded wall”, when he and backing vocalist Antonia Maass BOWIE during the album sessions, but remained (Maaß) embraced in front of Bowie as he looked an instrumental until towards the out of the Hansa Studio window. Bowie’s habit in end of production. The quotation the period following the song’s release was to say marks in the title of the song, a that the protagonists were based on an anonymous “’Heroes’” is a song written deliberate affectation, were young couple but Visconti, who was married to by David Bowie and Brian Eno in 1977. designed to impart an Mary Hopkin at the time, contends that Bowie was Produced by Bowie and Tony Visconti, it ironic quality on the protecting him and his affair with Maass. Bowie was released both as a single and as the otherwise highly confirmed this in 2003. title track of the album “Heroes”. A product romantic, even The music, co-written by Bowie and Eno, has of Bowie’s “Berlin” period, and not a huge hit in been likened to a Wall of Sound production, an the UK or US at the time, the song has gone on undulating juggernaut of guitars, percussion and to become one of Bowie’s signature songs and is synthesizers. -

Dec. 22, 2015 Snd. Tech. Album Arch

SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) Affinity-Affinity S=Trident Studio SOHO, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R=1970 (Vertigo) E=Frank Owen, Robin Geoffrey Cable P=John Anthony SOURCE=Ken Scott, Discogs, Original Album Liner Notes Albion Country Band-Battle of The Field S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Island Studio, St. Peter’s Square, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=1973 (Carthage) E=John Wood P=John Wood SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Albion Dance Band-The Prospect Before Us S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (PARTIALLY TRACKED. MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Olympic Studio #1 Studio, Barnes, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=Mar.1976 Rel. (Harvest) @ Sound Techniques, Olympic: Tracks 2,5,8,9 and 14 E= Victor Gamm !1 SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) P=Ashley Hutchings and Simon Nicol SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Alice Cooper-Muscle of Love S=Sunset Sound Recorders Hollywood, CA. Studio #2. (TRACKED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Record Plant, NYC, A&R Studio NY (OVERDUBS AND MIX) R=1973 (Warner Bros) E=Jack Douglas P=Jack Douglas and Jack Richardson SOURCE: Original Album liner notes, Discogs Alquin-The Mountain Queen S= De Lane Lea Studio Wembley, London (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R= 1973 (Polydor) E= Dick Plant P= Derek Lawrence SOURCE: Original Album Liner Notes, Discogs Al Stewart-Zero She Flies S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. -

Angelheaded Hipster: the Songs of Marc Bolan & T.Rex (BMG) September 16, 2020

Album Review: Angelheaded Hipster: The Songs of Marc Bolan & T.Rex (BMG) September 16, 2020 A stellar ensemble of artists which include Nick Cave, Lucinda Williams, Todd Rundgren, Joan Jett, two sons of John Lennon amongst others, lay down a worthy and often inspired double album’s worth of classic Marc Bolan songs. Preceding his induction to the Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame later in November this year. Angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection. Alan Ginsberg’s Howl and the Beats were one creative well from which the persona of Marc Bolan arose. He regarded himself as a poet foremost, around which he constructed melodies. Variations on twelve bar blues. Published his collected poems The Warlock of Love in 1969. Sold 40,000 but not well received by some critics. Producer Hal Willner regarded him as a serious writer of the calibre of Kurt Weill, Thelonious Monk and Charles Mingus. He passed away in April this year. Grateful for all his past inuences. Played in skife bands. In a trio with Helen Shapiro. Took notice of Phil Spector, Bob Dylan, Dion and the Belmonts. Looked like Dylan for a while. Marc’s father was a Russian Jew. At some point Feld became Bolan. To mirror Chuck Berry, he then became the English Poet of Rock’n’Roll. From 1970 to 1973 he took over from the recently split Beatles in popularity. Appeared in Ringo Starr’s lm Born to Boogie. Started Glam Rock. David Bowie took lessons and came up with Ziggy Stardust. We needed him to give us something to listen to when all that Prog Rock noodling was spilling over. -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Your Pretty Face Is Going to Hell the Dangerous Glitter of David Bowie, Iggy Pop,And Lou Reed

PF00fr(i-viii;vibl) 9/3/09 4:01 PM Page iii YOUR PRETTY FACE IS GOING TO HELL THE DANGEROUS GLITTER OF DAVID BOWIE, IGGY POP,AND LOU REED Dave Thompson An Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation New York PF00fr(i-viii;vibl) 9/16/09 3:34 PM Page iv Frontispiece: David Bowie, Iggy Pop, and Lou Reed (with MainMan boss Tony Defries laughing in the background) at the Dorchester Hotel, 1972. Copyright © 2009 by Dave Thompson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, with- out written permission, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review. Published in 2009 by Backbeat Books An Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation 7777 West Bluemound Road Milwaukee, WI 53213 Trade Book Division Editorial Offices 19 West 21st Street, New York, NY 10010 Printed in the United States of America Book design by David Ursone Typography by UB Communications Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Thompson, Dave, 1960 Jan. 3- Your pretty face is going to hell : the dangerous glitter of David Bowie, Iggy Pop, and Lou Reed / Dave Thompson. — 1st paperback ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and discography. ISBN 978-0-87930-985-5 (alk. paper) 1. Bowie, David. 2. Pop, Iggy, 1947-3. Reed, Lou. 4. Rock musicians— England—Biography. 5. Punk rock musicians—United States—Biography. I. Title. ML400.T47 2009 782.42166092'2—dc22 2009036966 www.backbeatbooks.com PF00fr(i-viii;vibl) 9/3/09 4:01 PM Page vi PF00fr(i-viii;vibl) 9/3/09 4:01 PM Page vii CONTENTS Prologue . -

Don Shaw (Scnptwn~Ter) Page 1 of 2

Don Shaw (Scnptwn~ter) Page 1 of 2 Don Shaw (Scriptwriter). "The stress today is on film punctuation. They want to keep the story flowing... They want a lot of action. Don Shaw wrote a total of four episodes for Survivors, all of them extremely well written. One of them, Mad Dog, was one of the highlights of the entire series. He is also well known for his contributions to Doom watch and his recent BBC series, Dangerfield. How did Don start out on his career as a scriptwriter? "I started out by acting in radio plays while I was still a teacher. I had actually been to Sandhurst as an officer cadet with King Hussein of Jordan, King Feisal of Iraq and the Duke of Kent. I didn't like the army, so I finished my national service and became a teacher. It was while I was teaching that I passed a BBC audition in Birmingham and acted in a number of radio plays, and from that I learned how to write a radio script. I wrote a number of radio plays, and then I acquired a literary agent who told me that if I wanted to make a living out of writing then I ought to go into television. She introduced me to Gerry Davis, who was my first contact. I met Gerry with another writer, Roy Clarke, who now writes Last of the Summer Wine. They turned down one of his scripts but did mine. From that I moved on to Thirty Minute Theatre with Innes Lloyd, who became a very famous producer. -

Marc Bolan the Best of '72-'77 - Volume Two Mp3, Flac, Wma

Marc Bolan The Best Of '72-'77 - Volume Two mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: The Best Of '72-'77 - Volume Two Country: UK Released: 1998 Style: Glam MP3 version RAR size: 1849 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1459 mb WMA version RAR size: 1164 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 689 Other Formats: MP2 MP4 DMF ASF WMA AA AIFF Tracklist 1-1 Rock On 3:26 1-2 The Slider 3:21 1-3 Baby Boomerang 2:16 1-4 Buick Mackane 3:29 1-5 Main Man 4:12 1-6 Tenement Lady 2:54 1-7 Broken-Hearted Blues 2:02 1-8 Country Honey 1:46 1-9 Electric Slim & The Factory Hen 3:02 1-10 Highway Knees 2:32 1-11 Explosive Mouth 2:26 1-12 Liquid Gang 3:17 1-13 Interstellar Soul 3:26 1-14 Solid Baby 2:36 1-15 Space Boss 2:47 1-16 Zip Gun Boogie 3:18 1-17 Think Zinc 3:20 1-18 Sensation Boulevard 3:48 1-19 Dreamy Lady 2:51 1-20 Ride My Wheels 2:25 2-1 Theme For A Dragon 2:00 2-2 Dawn Storm 3:42 2-3 Dandy In The Underworld 4:33 2-4 I'm A Fool For You Girl 2:16 2-5 I Love To Boogie 2:14 2-6 Jason B. Sad 3:22 2-7 Groove A Little 3:24 2-8 Sugar Baby 1:39 2-9 Fast Blues - Easy Action 3:22 2-10 Sky Church Music 4:15 2-11 Sad Girl 0:54 2-12 (By The Light Of A) Magical Moon 3:03 2-13 Petticoat Lane 2:42 2-14 Hot George 1:40 2-15 Classic Rap 2:14 2-16 Funky London Childhood 2:25 2-17 Jeepster [Live] 4:05 2-18 Telegram Sam [Live] 7:08 2-19 Debora [Live] 3:59 2-20 Hot Love [Live] 3:31 Companies, etc. -

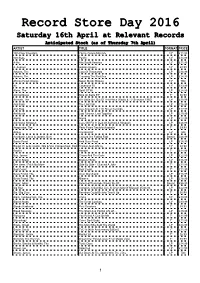

Record Store Day 2016

Record Store Day 2016 Saturday 16th April at Relevant Records Anticipated Stock (as of Thursday 7th April) ARTIST TITLE FORMAT PRICE 13th Floor Elevators You're Gonna Miss Me 10" £11.99 808 State Pacific 12" £14.99 A-Ha Hits South America 12" £11.99 A. Avenue Golden Queen 12" £8.99 Adverts, The Cast Of Thousands LP £18.99 Adverts, The Crossing The Red Sea LP £24.99 African Head Charge Super Mystic Brakes 10" TBC Air Casanova 70 12" £13.99 Alarm, The Spirit Of '86 LP £24.99 Animal Noise Sink Or Swim EP 7" £6.99 Animals, The We Gotta Get Out Of This Place (Radio & TV Sessions 1965) LP £18.99 Anti Pasti The Last Call LP £16.99 Anti-Flag Live Acoustic At 11th Street Records LP £17.99 Architects Lost Forever, Lost Together LP £19.99 Arena Arena LP £22.99 Ashford & Simpson Love Will Fix It: Best Of Ashford & Simpson LP £26.99 Associates, The Party Fears Two b/w Australia 7" £9.99 Atreyu The Best Of LP TBC Auerbach, Loren & Jansch, Bert Colours Are Fading Fast Boxset £48.99 Bardo Pond Acid Guru Pond LP £26.99 Bargel, R. & de Caster, Nils & Van Campenhout, Rola Frankie And Johnny 10" £8.99 Bastille Hangin' 7" £11.99 Bay, James Chaos And The Calm LP £22.99 Beach Slang Broken Thrills 12" £16.99 Bee Gees / Faith No More Side By Side - I Started A Joke 7" £11.99 Best Coast Best Coast 7" £11.99 Bevis Frond, The Inner Marshland LP £18.99 Bevis Frond, The Miasma LP £18.99 Beyer, Adam Selected Drumcode Works 96 -00 Boxset £56.99 Big Star Complete Columbia: Live At University Of Missouri 25.04.93 LP £22.99 Bis / Big Zero Boredom Could Be b/w Tear It Up -

An Encyclopedia of the Legends Who Changed Music Forever, Scott Schinder, Andy Schwartz, ABC-CLIO, 2007, 0313338450, 9780313338458, 680 Pages

Icons of Rock: An Encyclopedia of the Legends Who Changed Music Forever, Scott Schinder, Andy Schwartz, ABC-CLIO, 2007, 0313338450, 9780313338458, 680 pages. More than half a century after the birth of rock, the musical genre that began as a rebellious underground phenomenon is now acknowledged as America's-and the world's-most popular and influential musical medium, as well as the soundtrack to several generations' worth of history. From Ray Charles to Joni Mitchell to Nirvana, rock music has been an undeniable force in both reflecting and shaping our cultural landscape. Icons of Rock offers a vivid overview of rock's pervasive role in contemporary society by profiling the lives and work of the music's most legendary artists.Most rock histories, by virtue of their all-encompassing scope, are unable to cover the lives and work of individual artists in depth, or to place those artists in a broader context. This two-volume set, by contrast, provides extensive biographies of the 24 greatest rock n' rollers of all time, examining their influences, innovations, and impact in a critical and historical perspective. Entries inside this unique reference explore the issues, trends, and movements that defined the cultural and social climate of the artists' music. Sidebars spotlight the many iconic elements associated with rock, such as rock festivals, protest songs, and the British Invasion. Providing a wealth of information on the icons, culture, and mythology of America's most beloved music, this biographical encyclopedia will serve as an invaluable resource for students and music fans alike.. All Music Guide The Definitive Guide to Popular Music, Vladimir Bogdanov, Chris Woodstra, Stephen Thomas Erlewine, 2001, Music, 1491 pages.