1 17 MAY 2016 How Did Wizz Air Become Central and Eastern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WORLD AVIATION Yearbook 2013 EUROPE

WORLD AVIATION Yearbook 2013 EUROPE 1 PROFILES W ESTERN EUROPE TOP 10 AIRLINES SOURCE: CAPA - CENTRE FOR AVIATION AND INNOVATA | WEEK startinG 31-MAR-2013 R ANKING CARRIER NAME SEATS Lufthansa 1 Lufthansa 1,739,886 Ryanair 2 Ryanair 1,604,799 Air France 3 Air France 1,329,819 easyJet Britis 4 easyJet 1,200,528 Airways 5 British Airways 1,025,222 SAS 6 SAS 703,817 airberlin KLM Royal 7 airberlin 609,008 Dutch Airlines 8 KLM Royal Dutch Airlines 571,584 Iberia 9 Iberia 534,125 Other Western 10 Norwegian Air Shuttle 494,828 W ESTERN EUROPE TOP 10 AIRPORTS SOURCE: CAPA - CENTRE FOR AVIATION AND INNOVATA | WEEK startinG 31-MAR-2013 Europe R ANKING CARRIER NAME SEATS 1 London Heathrow Airport 1,774,606 2 Paris Charles De Gaulle Airport 1,421,231 Outlook 3 Frankfurt Airport 1,394,143 4 Amsterdam Airport Schiphol 1,052,624 5 Madrid Barajas Airport 1,016,791 HE EUROPEAN AIRLINE MARKET 6 Munich Airport 1,007,000 HAS A NUMBER OF DIVIDING LINES. 7 Rome Fiumicino Airport 812,178 There is little growth on routes within the 8 Barcelona El Prat Airport 768,004 continent, but steady growth on long-haul. MostT of the growth within Europe goes to low-cost 9 Paris Orly Field 683,097 carriers, while the major legacy groups restructure 10 London Gatwick Airport 622,909 their short/medium-haul activities. The big Western countries see little or negative traffic growth, while the East enjoys a growth spurt ... ... On the other hand, the big Western airline groups continue to lead consolidation, while many in the East struggle to survive. -

Data Standards Manual Summary of Changes

October 2019 Visa Public gfgfghfghdfghdfghdfghfghffgfghfghdfghfg This document is a supplement of the Visa Core Rules and Visa Product and Service Rules. In the event of any conflict between any content in this document, any document referenced herein, any exhibit to this document, or any communications concerning this document, and any content in the Visa Core Rules and Visa Product and Service Rules, the Visa Core Rules and Visa Product and Service Rules shall govern and control. Merchant Data Standards Manual Summary of Changes Visa Merchant Data Standards Manual – Summary of Changes for this Edition This is a global document and should be used by members in all Visa Regions. In this edition, details have been added to the descriptions of the following MCCs in order to facilitate easier merchant designation and classification: • MCC 5541 Service Stations with or without Ancillary Services has been updated to include all engine fuel types, not just automotive • MCC 5542 Automated Fuel Dispensers has been updated to include all engine fuel types, not just automotive • MCC 5812 Eating Places, Restaurants & 5814 Fast Food Restaurants have been updated to include greater detail in order to facilitate easier segmentation • MCC 5967 Direct Marketing – Inbound Telemarketing Merchants has been updated to include adult content • MCC 6540 Non-Financial Institutions – Stored Value Card Purchase/Load has been updated to clarify that it does not apply to Staged Digital Wallet Operators (SDWO) • MCC 8398 Charitable Social Service Organizations has -

Notice of Annual General Meeting 24 July 2018 at 1.00 P.M

Notice of Annual General Meeting 24 July 2018 at 1.00 p.m. (CEST) to be held at World Trade Centre I Route de l’Aéroport 10 1216 Cointrin Geneva, Switzerland THIS NOTICE IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt as to any aspect of the proposals referred to in this Notice or as to the action you should take, you should seek advice from a stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or other independent professional adviser who is duly authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 if you are in the United Kingdom, or another appropriately authorised independent adviser if you are in a territory outside the United Kingdom. If you have sold or otherwise transferred all of your ordinary shares in Wizz Air Holdings Plc please send this Notice, together with the accompanying documents, at once to the relevant purchaser or transferee, or to the stockbroker, bank or agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the relevant purchaser or transferee. A Form of Proxy for use at the Annual General Meeting is enclosed with this Notice. Notes on completing and returning the Form of Proxy can be found in the Form of Proxy and this Notice and should be read carefully before the Form of Proxy is completed. Wizz Air Holdings Plc Notice of Annual General Meeting EU-DOCS\21196750.7 Wizz Air Holdings Plc Company Number: 103356 44 Esplanade, St. Helier JE4 9WG Jersey, Channel Islands 24 May 2018 Dear Shareholder, ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF THE COMPANY – 24 JULY 2018 I am pleased to enclose the Notice convening the forthcoming annual general meeting (“AGM”) of Wizz Air Holdings Plc (the “Company”) which will be held at World Trade Centre I, Route de l’Aéroport 10, 1216 Cointrin, Geneva, Switzerland on 24 July 2018 at 1.00 p.m. -

Foreign ICAO 3LD Additions, Deletions, and Modifications (Excluding U.S.)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION N JO 7340.470 NOTICE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION Air Traffic Organization Policy Effective Date: July 11, 2018 Cancellation Date: July 11, 2019 SUBJ: Foreign ICAO 3LD Additions, Deletions, and Modifications (excluding U.S.) 1. Purpose of This Notice. This notice modifies FAA Order JO 7340.2, Contractions, Chapter 3, Sections 1, 2, and 3, !CAO Aircraft Company Three-Letter Identifier and/or Telephony Designator. This notice reflects recent changes initiated by countries other than the United States (U.S.) including new ICAO three letter designators (3LDs), deletions ofdefunct ICAO 3LDs, and modifications to ICAO 3LDs, associated telephonies, and companies/agencies. This Notice supplements FAA Order JO 7340.2 until the additions and modifications are incorporated into the Order. This Notice does not replace or substitute for GENOTs issued by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Air Traffic Organization (ATO) for ICAO 3LDs assigned and authorized for U.S. aircraft operators. 2. Audience. This notice applies to the following Air Traffic Organization (ATO) service units: Air Traffic Services, and System Operations Services; ATO Safety and Technical Training; and all associated air traffic control facilities. This notice is informational in nature and does not require documentation as supplemental training in FAA Form 3120-1, Training and Proficiency Record. 3. Where Can I Find This Notice? This notice is available on the MyFAA employee website at https://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_ notices/ and on the air traffic publications website at http://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/. 4. Source Document. The source document for the ICAO 3LD additions and modifications contained in this notice is ICAO Document 8585, Designatorsfor Aircraft Operating Agencies, Aeronautical Authorities, and Services. -

17 1 3 Ifm Mag Rfq Submission

Confidential [email protected] 2020-01-16 15:20:10 +0000 St. Louis Lambert International Airport RFQ Submission November 1, 2019 ifm MAG 1 Cover letter ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 2 Executive Summary and Strategic Rationale ....................................................................................................................... 2 3 Description of the IFM Investors Team ............................................................................................................................... 4 3.1 Description of Team Members .................................. ........................ ..................... .. ...................... .. ...................... .. ................ .. 4 4 Operational and Management Capability ........................................................................................................................... 5 4.1 Operational and Maintenance Expertise ............................................................................................................ ................ .. .... .. 6 4.2 Capital Improvement Experience ................... ...... .. ................ ...... .. ................ .. ... ...... .. ... ............. ...... .. ... ............. ...... .. ... ........... 15 4.3 Customer Service ......................................................................................................................................... -

Schroder UK Mid Cap Fund

Schroder UK Mid Ca p Fund plc Half Year Report and Accounts For the six months ended 31 March 2020 Key messages – Portfolio of “high conviction” stocks aiming to provide a total return in excess of the FTSE 250 (ex-Investment Companies) Index and an attractive level of yield. – Dividend has tripled since 2007 as portfolio investments have captured the cash generative nature of investee companies, in a market where income has become an increasingly important part of our investors’ anticipated returns. – Provides exposure to dynamic mid cap companies that have the potential to grow to be included in the FTSE 100 index, which are at an interesting point in their life cycle, and/or which could ultimately prove to be attractive takeover targets. – Proven research driven investment approach based on the Manager’s investment process allied with a strong selling discipline. – Managed by Andy Brough and Jean Roche with a combined 50 years’ investment experience 1, the fund has a consistent, robust and repeatable investment proces s. 1Andy Brough became Lead Manager on 1 April 2016 . Investment objective Schroder UK Mid Cap Fund plc’s (the “Company”) investment objective is to invest in mid cap equities with the aim of providing a total return in excess of the FTSE 250 (ex -Investment Companies) Index. Investment policy The strategy is to invest principally in the investment universe associated with the benchmark index, but with an element of leeway in investment remit to allow for a conviction-driven approach and an emphasis on specific companies and targeted themes. The Company may also invest in other collective investment vehicles where desirable, for example to provide exposure to specialist areas within the universe. -

Investment in Air Transport Infrastructure

Guidance for developing private participation Infrastructure Transport Air Investment in Public Disclosure Authorized Investment in Air Transport Infrastructure Guidance for developing Public Disclosure Authorized private participation Mustafa Zakir Hussain, Editor With case studies prepared by Booz Allen Hamilton Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Investment in Air Transport Infrastructure Guidance for developing private participation Investment in Air Transport Infrastructure Guidance for developing private participation Mustafa Zakir Hussain, Editor With case studies prepared by Booz Allen Hamilton © 2010 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Direc- tors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorse- ment or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of appli- cable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. -

The Week Ahead, 5Th October 2020

The Week Ahead, 5th October 2020 ANALYSTS BACKGROUND Fiona has a deep understanding of market fundamentals gained through 14 years’ experience in the financial markets. She provides up to the minute analysis and insight into the financial markets, as well as the broader economy and monetary policy in the UK, Europe, US and Asia. She is regularly quoted in the global financial press, with her name often seen on Bloomberg, Reuters, Financial Times and the Telegraph. Fiona is a familiar face after years of regular TV appearances across the globe on the likes of BBC, Sky News and Reuters. Our pick of the top macro data points and companies reporting this week. Those in bold are discussed below. ECONOMIC DATA Global Services PMI UK Services PMI Monday 5th October EZ Retail Sales US ISM Non-Mfg RBA Rate Decision UK Construction PMI Tuesday 6th October Germany Factory Orders US Trade Balance German Industrial Production Halifax House Prices Wednesday 7th October EIA Crude Inventories US FOMC Minutes Germany Trade Balance Thursday 8th October US Initial Jobless Claims China Caixin Services PMI Friday 9th October UK Trade Balance UK Monthly GDP COMPANY ANNOUNCEMENTS Monday 5th October Wizz Air Ferrexpo Restaurant Group Tuesday 6th October easyJet Air France KLM Levi Strauss (US) Wednesday 7th October Tesco Imperial Brands GVC Thursday 8th October Electrocomponents CMC Markets Delta Air (US) JD Wetherspoons (delayed) Friday 9th October Stagecoach KEY THEME Trump, Covid & Brexit Risk aversion surged at the end of last week after President Trump unexpectedly contracted Covid with just one month to go until the US Presidential elections. -

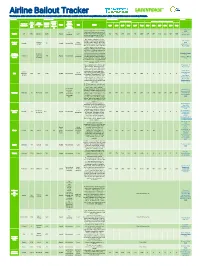

European Airline Bailout Tracker Reflects the Most up to Date Public Information Available at the Time It Was Published on June 9, 2021

Airline Bailout Tracker This European airline bailout tracker reflects the most up to date public information available at the time it was published on June 9, 2021. Financial data based on research by Profundo. Company Bailout amount Financial results Sources Amount Binding Net profits (mln €) Dividends + share buybacks (mln €) 2018 Airline/ Amount (mln €) - climate Country of Passen subsidiarie (mln €) - Under Status conditions Type Details registration gers 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 Total 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 Total (mln) s Agreed discussi Private on dividend ban Guardian, 6 April An initial government loan of GBP 2020 600m (ca €670m) was provided at No Reuters, 11 EasyJet UK 88.5 EasyJet 2240 Agreed Loan the start of the crisis, followed with a 393 402 246 505 742 2288 214 281 195 272 421 1383 dividends January 2021 government backed loan of GBP 1,4 bn (ca €1,570m) in January 2021. One-quarter of Norway’s rescue package for airlines (loan guarantee e24, 20 April Regional Regional Loan of NOK 6 billion ($549 million)) will 2020 Norway 121 Agreed No condition - - - - - - - - - - - - carriers carriers guarantee be divided between Widerøe, which Aeronautics, 20 offers key regional service, and other March 2020 small regional airline operators. Total pot of €455m has been made available to all airlines registered in Sweden. SAS has been loaned €137m and that has been deducted Euractiv, 13 April All airlines All airlines Loan from this amount and included in the 2020 operating in Sweden operating 318 Agreed No condition - - - - - - - - - - - - guarantee overall support provided to SAS by Finans, 17 March Sweden in Sweden Sweden and other countries, detailed 2020 the row below. -

Schroder UK Mid Cap Fund Plc Unaudited Portfolio Holdings at 31St July 2020

Schroder UK Mid Cap Fund plc Unaudited portfolio holdings at 31st July 2020 The investments listed below have been valued on a fair value basis using closing bid prices. Market Nominal value Investment SEDOL ISIN holding £ 4Imprint Group Ord GBP0.385 664097 GB0006640972 105,000 2,493,750 A G Barr Ord GBP0.04167 B6XZKY7 GB00B6XZKY75 700,000 2,999,500 Anglo Pacific Group Ord GBP0.02 644936 GB0006449366 2,050,000 2,423,100 Bodycote PLC Ord GBP0.173 B3FLWH9 GB00B3FLWH99 800,000 4,504,000 Brewin Dolphin Ord GBP0.01 176581 GB0001765816 1,610,000 4,218,200 Cairn Energy Ord GBP0.0136686 B74CDH8 GB00B74CDH82 2,300,000 2,748,500 Capita Plc B23K0M2 GB00B23K0M20 2,700,000 924,210 CLS Holdings Plc Ord GBP0.025 BF04459 GB00BF044593 1,749,950 3,415,902 Computacenter Plc Ord 0.075555 BV9FP30 GB00BV9FP302 300,000 5,943,000 Cranswick Ord GBP0.10 231888 GB0002318888 114,000 4,078,920 Crest Nicholson Holdings Ltd Ord GBP0.05 B8VZXT9 GB00B8VZXT93 800,000 1,496,000 Dechra Pharmaceuticals Ord GBP0.01 963318 GB0009633180 143,310 4,087,201 Diploma Ord GBP0.05 182663 GB0001826634 320,000 5,801,600 Dunelm Group GBP.01 B1CKQ73 GB00B1CKQ739 790,000 9,709,100 Fisher (James) Ord GBP0.25 339500 GB0003395000 266,000 3,037,720 Future PLC Ord GBP0.15 BYZN904 GB00BYZN9041 212,000 2,925,600 Games Workshop Ord GBP0.05 371847 GB0003718474 80,000 7,024,000 Gamesys Group Plc Ord NPV BZ14BX5 GB00BZ14BX56 132,072 1,226,949 Genus Ord GBP0.10 207458 GB0002074580 80,000 2,716,800 Grafton Group New Units B00MZ44 IE00B00MZ448 530,000 3,407,900 Grainger Ord GBP0.05 B04V127 GB00B04V1276 -

FTSE Russell Publications

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE 250 Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) 3i Infrastructure 0.43 UNITED Bytes Technology Group 0.23 UNITED Edinburgh Investment Trust 0.25 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM 4imprint Group 0.18 UNITED C&C Group 0.23 UNITED Edinburgh Worldwide Inv Tst 0.35 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM 888 Holdings 0.25 UNITED Cairn Energy 0.17 UNITED Electrocomponents 1.18 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aberforth Smaller Companies Tst 0.33 UNITED Caledonia Investments 0.25 UNITED Elementis 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aggreko 0.51 UNITED Capita 0.15 UNITED Energean 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Airtel Africa 0.19 UNITED Capital & Counties Properties 0.29 UNITED Essentra 0.23 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AJ Bell 0.31 UNITED Carnival 0.54 UNITED Euromoney Institutional Investor 0.26 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Alliance Trust 0.77 UNITED Centamin 0.27 UNITED European Opportunities Trust 0.19 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Allianz Technology Trust 0.31 UNITED Centrica 0.74 UNITED F&C Investment Trust 1.1 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AO World 0.18 UNITED Chemring Group 0.2 UNITED FDM Group Holdings 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Apax Global Alpha 0.17 UNITED Chrysalis Investments 0.33 UNITED Ferrexpo 0.3 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ascential 0.4 UNITED Cineworld Group 0.19 UNITED Fidelity China Special Situations 0.35 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ashmore -

PROSPECTS of UKRAINE LOW-COST AVIATION Modern

114 ISSN 1813-1166 print / ISSN 2306-1472 online. Proceedings of the National Aviation University. 2016. N 2(67): 114–120 UDC 338.47 DOI: 10.18372/2306-1472.67.10440 Nataliia Kasianova1, Kateryna Suvorova2 PROSPECTS OF UKRAINE LOW-COST AVIATION National Aviation University 1, Kosmonavta Komarova avenue, 03680, Kyiv, Ukraine E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Purpose: The purpose of the article is to show that the budgetary development of aviation in the market of domestic flights in Ukraine will not only increase the use of the aircraft by the end user, but also maximize the profits for the domestic airlines. Methods: We used economic analysis methods to assess the costs for air travel. The necessity of the use of passengers load factor was justified, indicators of the efficiency of the airline were calculated. The advantages of the air transport compared to the rail transport were shown on the basis of a comparative analysis. Results: We considered the relationship between the volume of air traffic and the revenue of the potential clients. The feasibility of reducing prices on air tickets to the level of railway tariffs was proved. The concept of low cost airlines was defined, the factors to decrease the air travel prices were identified. Maximisation of the airline profits can be achieved with an affordable price, which will increase passenger traffic. Discussion: In Ukraine there is an urgent need for new solutions that would help airlines to successfully conduct its business and meet the needs of passengers on domestic routes. There is no doubt that in times of economic crisis, inflation has a significant impact on the real incomes of consumers, and this study proves the feasibility of establishing a low-budget domestic aviation and its use on domestic routes during the economic crisis.