Jun 3, 2019, 10:19Am Vat of Ancient Fish Sauce May Confirm Date That Pompeii Was Destroyed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components

RECIPE GARUM OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components Grilled strawberries Red oxalis Veal head Pickled maple blossom Marmande D‘Antan tomatoes (8-10 cm Ø) Green juniper powder Tomato gelée Garum sauce Tomato/raspberry gel Lovage oil GRILLED MARMANDE TOMATO STRAWBER- D‘ANTAN GELÉE RIES TOMATOES Grill the red strawberries (not too Blanch and peel the tomatoes. 220 g clear tomato stock* sweet) and cut them into 3 mm Carefully cut them into 28 g slices 1,6 g Agar cubes, spread them out and chill so that the slices retain the shape 0,6 g Gelatine immediately. of the tomatoes. Place the slices 0,4 g of citrus next to each other on a deep Tomami (hearty) baking tray and cover with green White balsamic vinegar juniper oil heated to 100°C, leave to stand for at least 6 hours. Flavor the tomato stock* with tomami, vinegar, salt and sugar. Then bind with texturizers and pour on a plastic tray. Afterwards cut out circles with a ring (9 cm Ø). *(mix 1 kg of tomatoes with salt, put in a kitchen towel and place over a container to drain = stock) CHAUSSEESTRASSE 8 D-10115 BERLIN MITTE TEL. +49 30.24 62 87 60 MAIL: [email protected] TOMATO/ GARUM TROUT RASPBERRY SAUCE GARUM GEL 100 ml tomato stock* 1 L poultry stock from heavily 1 part trout (without head, fins 15 g fresh raspberries roasted poultry carcasses. and offal) Pork pancreas Sea salt Flavored with 20 g Kombu (5 % of trout weight) algae for for 30 minutes. Water (80 % of trout Mix everything together and 55 g Sauerkraut (with bacon) weight) Sea salt (10 % of strain through a fine sieve. -

200 Bc - Ad 400)

ARAM, 13-14 (2001-2002), 171-191 P. ARNAUD 171 BEIRUT: COMMERCE AND TRADE (200 BC - AD 400) PASCAL ARNAUD We know little of Beirut's commerce and trade, and shall probably continue to know little about this matter, despite a lecture given by Mrs Nada Kellas in 19961. In fact, the history of Commerce and Trade relies mainly on both ar- chaeological and epigraphical evidence. As far as archaeological evidence is concerned, one must remember that only artefacts strongly linked with ceram- ics, i.e. vases themselves and any items, carried in amphoras, (predominantly, but not solely, liquids, can give information about the geographical origin, date and nature of such products. The huge quantities of materials brought to the light by recent excavations in Beirut should, one day, provide us with new evi- dence about importations of such products in Beirut, but we will await the complete study of this material, which, until today by no means provided glo- bal statistics valid at the whole town scale. The evidence already published still allows nothing more than mere subjective impressions about the origins of the material. I shall try nevertheless to rely on such impressions about that ma- terial, given that we lack statistics, and that it is impossible to infer from any isolated sherd the existence of permanent trade-routes and commercial flows. The results of such an inquiry would be, at present, worth little if not con- fronted with other evidence. On the other hand, it should be of great interest to identify specific Berytan productions among the finds from other sites in order to map the diffusion area of items produced in Beirut and the surrounding territory. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

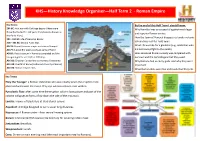

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi Di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) During the Fourth Century AD

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. by Maria Gabriella Bruni A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classical Archaeology in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Committee in Charge Professor Christopher H. Hallett, Chair Professor Ronald S. Stroud Professor Anthony W. Bulloch Professor Carlos F. Noreña Fall 2009 The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. Copyright 2009 Maria Gabriella Bruni Dedication To my parents, Ken and my children. i AKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to my advisor Professor Christopher H. Hallett and to the other members of my dissertation committee. Their excellent guidance and encouragement during the major developments of this dissertation, and the whole course of my graduate studies, were crucial and precious. I am also thankful to the Superintendence of the Archaeological Treasures of Reggio Calabria for granting me access to the site of the Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and its archaeological archives. A heartfelt thank you to the Superintendent of Locri Claudio Sabbione and to Eleonora Grillo who have introduced me to the villa and guided me through its marvelous structures. Lastly, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my husband Ken, my sister Sonia, Michael Maldonado, my children, my family and friends. Their love and support were essential during my graduate -

Ebook Download the Story of Garum : Fermented Fish Sauce and Salted

THE STORY OF GARUM : FERMENTED FISH SAUCE AND SALTED FISH IN THE ANCIENT WORLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sally Grainger | 352 pages | 31 Dec 2020 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9781138284074 | English | London, United Kingdom The Story of Garum : Fermented Fish Sauce and Salted Fish in the Ancient World PDF Book Buying colatura this weekend. From published tituli picti in CIL, the majority of liquamen labels are on amphorae, while named and exclusive garum is largely found on the much smaller urceii. Strain through cheesecloth and cool. When a fish sauce substitute cannot be found, either salt or a mixture of salt and anchovy heated in olive oil, and then mashed up can suffice. Mix some dried aneth, anis, fennel seeds, laurel, black pepper and lovage and mix the resulting powder with nuoc mam. Older Stories. I actually prefer the taste of salt cod to fresh. Cite Share. Google or read the ingredients of a bottle and look for the word anchovy. In what follows I will offer a radically new way to approach the dilemma of how to differentiate between the various fish sauces which takes account of the opinions of those who made, traded and used these products. You can use either garum or nuoc mam in our recipe. Thanks for the suggestion. This poem and amphorae tituli picti suggest that mackerel actually served as the best fish to use both for muria and garum. Stir the pasta and sauce together until the spaghetti is evenly coated. And yes, the NOMA book is some serious fermenting homework. According to the agricultural book Geoponica , the garum referred to as Haimation was among the very best. -

The Ruin of the Roman Empire

7888888888889 u o u o u o u THE o u Ruin o u OF THE o u Roman o u o u EMPIRE o u o u o u o u jamesj . o’donnell o u o u o u o u o u o u o hjjjjjjjjjjjk This is Ann’s book contents Preface iv Overture 1 part i s theoderic’s world 1. Rome in 500: Looking Backward 47 2. The World That Might Have Been 107 part ii s justinian’s world 3. Being Justinian 177 4. Opportunities Lost 229 5. Wars Worse Than Civil 247 part iii s gregory’s world 6. Learning to Live Again 303 7. Constantinople Deflated: The Debris of Empire 342 8. The Last Consul 364 Epilogue 385 List of Roman Emperors 395 Notes 397 Further Reading 409 Credits and Permissions 411 Index 413 About the Author Other Books by James J. O’ Donnell Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher preface An American soldier posted in Anbar province during the twilight war over the remains of Saddam’s Mesopotamian kingdom might have been surprised to learn he was defending the westernmost frontiers of the an- cient Persian empire against raiders, smugglers, and worse coming from the eastern reaches of the ancient Roman empire. This painful recycling of history should make him—and us—want to know what unhealable wound, what recurrent pathology, what cause too deep for journalists and politicians to discern draws men and women to their deaths again and again in such a place. The history of Rome, as has often been true in the past, has much to teach us. -

Fish Sauces – the Food That Made Rome Great by Benedict Lowe

Fish Sauces – The Food that Made Rome Great By Benedict Lowe Recent research has done much to stress the importance of fish in the ancient Roman diet. But there were many ways to consume fish. The most popular way to consume fish was fresh: according to Seneca the Romans could not taste a fish unless they saw it swimming in the dining room! A mullet was not considered fresh unless it had died in the hands of the banqueter about to eat it. Ownership of elaborate fishponds seems to have been quite a fad in the Late Republic with Cicero ridiculing their owners as piscinarium tritones. L. Licinius Lucullus even had a channel cut through a mountain in order to supply his fishponds at Baiae with sea water – prompting Pompey to dub him Xerxes togatus after the King of Persia who crossed the Hellespont. Large salt-water fishponds can still be seen in the Roman villas along the coast south of Rome. Submerged Roman Fishpond, Formia. Such was the popularity of fish on the tables of the elite that it may have resulted in depleted supplies due to over-fishing, leading to higher market values and a reliance upon imports. In the first century CE, the commander of the fleet at Misenum – Optatus – brought live parrot wrasses (scari) from the Southern Aegean to Latium where he scattered them at Ostia and the Tiber mouth and along the coast of Campania – presumably to replenish fish stocks depleted by the demands of the city of Rome. The satirist Juvenal paints a harrowing contrast between the fish imported from Corsica and Sicily enjoyed by the host of a dinner party, and the Tiber river pike bloated on sewage that is consumed by his poorer guests. -

Title: Some Reflections Concerning the Usage of "Liquamen" in the Roman Cookery

Title: Some reflections concerning the usage of "liquamen" in the Roman cookery Author: Patrycja Matusiak Citation style: Matusiak Patrycja. (2006). Some reflections concerning the usage of "liquamen" in the Roman cookery. "Scripta Classica" (Vol. 3 (2006), s. 57-67). Patrycja Matusiak University of Silesia, Katowice Some reflections concerning the usage of liquamen in the Roman cookery he abundance of tastes and smells was a characteristic feature of the Tancient cuisine, according to our present knowledge, of course. This wealth distinguishes the Roman cookery from modem European, especially Polish. The fish sauce was an indispensable ingredient of almost every dish. This sauce was called garum or liquamen, and was ubiquitous not only in Roman cuisine but also in Greek - its wide usage is reflected in literature. The earliest mentions of it are found in the works of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Cratinus, Pherecrates and Plato Comicus from 5th c. BC. Unfortunately our knowledge of this highly interesting aspect of ancient life is far from satisfactory, since the only complete source, an ancient “cookbook”, is Apicius’ De re coquinaria'. Apicius however was not the author of this treatise, which actually is a fourth-century CE compilation, handed down by his name. We can also find many recipes in the works of Cato and in other Roman authors writing on agriculture2; last, but not least, many a valuable information is scattered in casual descriptions all over the preserved Greco-Roman literature. These however, more often present an impressive picture of lavish feasts and refined dishes rather than give detailed recipes which would allow us to recon struct the ancient cuisine. -

Roman Amphora Trade Across the Straits of Gibraltar: an Ancient ‘Anti-Economic Practice’?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diposit Digital de la Universitat de Barcelona FELIX TEICHNER AND LLUÍS PONS PUJOL ROMAN AMPHORA TRADE ACROSS THE STRAITS OF GIBRALTAR: AN ANCIENT ‘ANTI-ECONOMIC PRACTICE’? Summary. Olive oil and fish products from the south of Hispania and North Africa played an important role in the Roman economy. The authors call attention to the asymmetrical distribution of archaeological data available on this subject, in particular the location of amphora kilns, and try to give an explanation, based on the evolution of European archaeology in the twentieth century. This paper focuses on Roman maritime trade in the ‘Circle of the Straits’,1 the area between the provinces of Baetica (Andalucia) and Mauretania Tingitana (Morocco), where ‘. both the Baetis and the Anas empty, and the limits of Maurusia, the Atlantic Ocean breaks in and thus forms the strait at the Pillars, and by this strait the interior sea connects with the exterior sea’ (Strabo III 1, 7: trans. H.L. Jones, Loeb edition 1923). It will not judge or discuss the question of rationality or irrationality in the ancient economy for which the reader is referred to the relevant recent bibliography (Rathbone 1991; Andreau and Maucourant 1999; Lo Cascio and Rathbone 2000; Scheidel and von Reden 2002; Christensen 2003; Andreau 2005; Carrié 2005; Lautman 2005; Minaud 2005; Rathbone 2005; Tchernia 2005). The historical and economic context is well known. From the beginning of the Roman occupation of the Iberian Peninsula, the fertile valley of the Baetis – the later Guadalquivir – played a key role in the Romanization of Iberia (Keay 1998). -

Vegetarianism

74 Vegetarianism It seems highly plausible that many people (perhaps even the overwhelming majority of the population) in the Graeco-Roman lands surrounding the Mediterranean would have existed upon a predominantly vegetarian diet.1 By this is signified not a diet from which animal flesh had been deliberately omitted, but rather one in which meat or fish would have been a rare occurrence owing to its relative scarcity and perhaps elevated price. The terms „meat‟ and „fish‟ should be used with a measure of caution. This thesis will look at each separately, regarding them as distinct and separate categories. Wilkins argues for the scholar to consider the separation between land and sea creatures in antiquity, as they each possess diverse and independent statuses: Fish are part of the wild, which is distinct from the tame and the farmed. The wild is divided into fish, birds and animals for hunting... Farmed animals were sacrificed; wild animals were not.2 He goes on to assert: If fish were outside this order and were part of the raw nature with which mankind was always struggling, then there was no need for fish sacrifice, no need for equal distribution of flesh. In other words, fish were part of the secular world.3 For Vernant, fish cannot be a part of the sacrificial ritual: the ox slain and carved by Prometheus at the first sacrifice is the domestic animal closest to man, the animal best integrated into his sphere of existence, 1 See previous chapter. 2 Wilkins (1993), 192. I am not sure whether the division is as bold and as clear-cut as Wilkins states. -

The Archaeology of Roman Surveillance in the Central Alentejo, Portugal

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF ROMAN SURVEILLANCE IN THE CENTRAL ALENTEJO, PORTUGAL CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES NUMBER 5 Editorial Board Chair: Donald Mastronarde Editorial Board: Alessandro Barchiesi, Todd Hickey, Emily Mackil, Richard Martin, Robert Morstein-Marx, J. Theodore Peña, Kim Shelton California Classical Studies publishes peer-reviewed long-form scholarship with online open access and print-on-demand availability. The primary aim of the series is to disseminate basic research (editing and analysis of primary materials both textual and physical), data-heavy re- search, and highly specialized research of the kind that is either hard to place with the leading publishers in Classics or extremely expensive for libraries and individuals when produced by a leading academic publisher. In addition to promoting archaeological publications, papyrolog- ical and epigraphic studies, technical textual studies, and the like, the series will also produce selected titles of a more general profile. The startup phase of this project (2013–2017) is supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Also in the series: Number 1: Leslie Kurke, The Traffic in Praise: Pindar and the Poetics of Social Economy, 2013 Number 2: Edward Courtney, A Commentary on the Satires of Juvenal, 2013 Number 3: Mark Griffith, Greek Satyr Play: Five Studies, 2015 Number 4: Mirjam Kotwick, Alexander of Aphrodisias and the Text of Aristotle’s Meta- physics, 2016 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF ROMAN SURVEILLANCE IN THE CENTRAL ALENTEJO, PORTUGAL Joey Williams CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES Berkeley, California © 2017 by Joey Williams. California Classical Studies c/o Department of Classics University of California Berkeley, California 94720–2520 USA http://calclassicalstudies.org email: [email protected] ISBN 9781939926081 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016963103 CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix List of Figures and Illustrations xi 1. -

Nichole Maron Lyle

THE USE OF GEOLOGICAL METHODS FOR THE CHARACTERIZATION OF ROMAN METALLURGICAL SLAG FROM THE EXCAVATIONS OF THE YASMINA CEMETERY IN CARTHAGE, TUNISIA by NICHOLE MARON LYLE (Under the direction of Samuel E. Swanson) ABSTRACT The fill material excavated from the Yasmina Cemetery in Carthage is comprised of a significant amount of metallurgical slag, but there have been no studies conducted on the slag to determine its chemical and mineralogical character or its relevance to Roman Carthaginian metallurgy. In order to do so, the slag was sampled from storage at the Museum of Carthage to assess the amount and types of metallurgical slag excavated from the site and to select representative samples for return to the University of Georgia Geology Department for petrographic and electron microprobe analyses. Based on the initial characterization, the slags indicate the presence of a small scale metals workshop skilled in a variety of metallurgical techniques consistent with those found elsewhere in the Roman Empire between the 2nd and 7th centuries AD, including the smelting and smithing of iron and copper and the use of lead in secondary metal refining processes. INDEX WORDS: Metallurgical slag, Carthage, Roman, Iron, Copper, Lead, Yasmina Cemetery THE USE OF GEOLOGICAL METHODS FOR THE CHARACTERIZATION OF ROMAN METALLURGICAL SLAG FROM THE EXCAVATIONS OF THE YASMINA CEMETERY IN CARTHAGE, TUNISIA by NICHOLE MARON LYLE A.B., The University of Georgia, 1998 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2002 © 2002 Nichole Maron Lyle All Rights Reserved.