Feminist and Queer Formations in Digital Networks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRIDE in LONDON CAB ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Page 1 of 9

PRIDE IN LONDON CAB ANNUAL REPORT 2017 PRIDE IN LONDON INDEPENDENT COMMUNITY ADVISORY BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2017 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The Independent Community Advisory Board (CAB) submits its annual report reviewing the 2017 Pride in London (Pride) events. This report reflects issues raised at the CAB private review meeting held on 20 July 2017, which were based on community feedback and matters identified from CAB members’ own experiences. This year, for the first time, the CAB has also sought feedback from a range of major stakeholder organisations within the LGBT+ community. Their comments have been included, but anonymised. 1.2 The CAB is independent from the organisation of Pride. It advises the London LGBT+ Community Pride CIC (LLCP) Board and scrutinises their decisions. It provides guidance on inclusion, governance and other operational issues. Its membership is drawn from different strands of London’s LGBT+ communities with the hope of being broadly representative. The membership of the CAB at the date of this report is: • Chair: Adrian Hyyrylainen-Trett • Arts and Literature: Simon Tarrant (Winter Pride) • Bisexual People's Rep: Edward Lord OBE JP (BiUK) (Deputy Chair) • Black, Asian & Minority Ethnic People's Rep: Ozzy Amir (QMSU) • Campaigning and Political Groups: Tom Wilson (LGBT Labour) • Disabled People's Rep: Vacant • Faith and Belief Groups: Vacant • Health Rep: Eleanor Barnwell (Kings College NHS Foundation Trust) • Local Groups Rep: David Robson (Wandsworth LGBT Forum) • Older People's Rep: Peter Scott-Presland (Opening -

Thefeminist Porn Bookintrocha

Introduction: The Politics of Producing Pleasure CONSTANCE PENLEY, CELINE PARREÑAS SHIMIZU, MIREILLE MILLER-YOUNG, and TRISTAN TAORMINO he Feminist Porn Book is the frst collection to bring together writ- ings by feminist porn producers and feminist porn scholars to Tengage, challenge, and re-imagine pornography. As collaborating editors of this volume, we are three porn professors and one porn direc- tor who have had an energetic dialogue about feminist politics and por- nography for years. In their criticism, feminist opponents of porn cast pornography as a monolithic medium and industry and make sweep- ing generalizations about its production, its workers, its consumers, and its efects on society. Tese antiporn feminists respond to feminist por- nographers and feminist porn professors in several ways. Tey accuse us of deceiving ourselves and others about the nature of pornography; they claim we fail to look critically at any porn and hold up all porn as empowering. More typically, they simply dismiss out of hand our abil- ity or authority to make it or study it. But Te Feminist Porn Book ofers arguments, facts, and histories that cannot be summarily rejected, by providing on-the-ground and well-researched accounts of the politics of producing pleasure. Our agenda is twofold: to explore the emergence and signifcance of a thriving feminist porn movement, and to gather some of the best new feminist scholarship on pornography. By putting our voices into conversation, this book sparks new thinking about the richness and complexity of porn as a genre and an industry in a way that helps us to appreciate the work that feminists in the porn industry are doing, both in the mainstream and on its countercultural edges. -

Turns to Affect in Feminist Film Theory 97 Anu Koivunen Sound and Feminist Modernity in Black Women’S Film Narratives 111 Geetha Ramanathan

European Film Studies Mutations and Appropriations in THE KEY DEBATES FEMINISMS Laura Mulvey and 5 Anna Backman Rogers (eds.) Amsterdam University Press Feminisms The Key Debates Mutations and Appropriations in European Film Studies Series Editors Ian Christie, Dominique Chateau, Annie van den Oever Feminisms Diversity, Difference, and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures Edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover design: Neon, design and communications | Sabine Mannel Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 676 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 363 4 doi 10.5117/9789089646767 nur 670 © L. Mulvey, A. Backman Rogers / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Editorial 9 Preface 10 Acknowledgments 15 Introduction: 1970s Feminist Film Theory and the Obsolescent Object 17 Laura Mulvey PART I New Perspectives: Images and the Female Body Disconnected Heroines, Icy Intelligence: Reframing Feminism(s) -

Feminisms 1..277

Feminisms The Key Debates Mutations and Appropriations in European Film Studies Series Editors Ian Christie, Dominique Chateau, Annie van den Oever Feminisms Diversity, Difference, and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures Edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover design: Neon, design and communications | Sabine Mannel Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 676 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 363 4 doi 10.5117/9789089646767 nur 670 © L. Mulvey, A. Backman Rogers / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Editorial 9 Preface 10 Acknowledgments 15 Introduction: 1970s Feminist Film Theory and the Obsolescent Object 17 Laura Mulvey PART I New Perspectives: Images and the Female Body Disconnected Heroines, Icy Intelligence: Reframing Feminism(s) and Feminist Identities at the Borders Involving the Isolated Female TV Detective in Scandinavian-Noir 29 Janet McCabe Lena Dunham’s Girls: Can-Do Girls, -

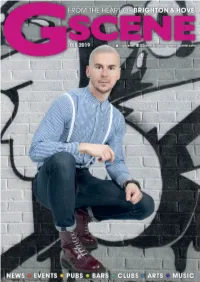

02 Gscene Feb2019

FEB 2019 CONTENTS GSCENE magazine ) www.gscene.com AFFINITY BAR t @gscene f GScene.Brighton PUBLISHER Peter Storrow TEL 01273 749 947 EDITORIAL [email protected] ADS+ARTWORK [email protected] EDITORIAL TEAM James Ledward, Graham Robson, Gary Hart, Alice Blezard, Ray A-J SPORTS EDITOR Paul Gustafson N ARTS EDITOR Michael Hootman R E SUB EDITOR Graham Robson V A T SOCIAL MEDIA EDITOR E N I Marina Marzotto R A DESIGN Michèle Allardyce M FRONT COVER MODEL Arkadius Arecki NEWS INSTAGRAM oi_boy89 SUBLINE POST-CHRISTMAS PARTY FOR SCENE STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER Simon Pepper, 6 News www.simonpepperphotography.com Instagram: simonpepperphotography f simonpepperphotographer SCENE LISTINGS CONTRIBUTORS 24 Gscene Out & About Simon Adams, Ray A-J, Jaq Bayles, Jo Bourne, Nick Boston, Brian Butler, 28 Brighton & Hove Suchi Chatterjee, Richard Jeneway, Craig Hanlon-Smith, Samuel Hall, Lee 42 Solent Henriques, Adam Mallaby, Enzo Marra, Eric Page, Del Sharp, Gay Socrates, Brian Stacey, Michael Steinhage, ARTS Sugar Swan, Glen Stevens, Duncan Stewart, Craig Storrie, Violet 46 Arts News Valentine (Zoe Anslow-Gwilliam), Mike Wall, Netty Wendt, Roger 47 Arts Matters Wheeler, Kate Wildblood ZONE 47 Arts Jazz PHOTOGRAPHERS Captain Cockroach, James Ledward, 48 Classical Notes Jack Lynn, Marina Marzotto 49 Page’s Pages REGULARS 26 Dance Music 26 DJ Profile: Lee Dagger 45 Shopping © GSCENE 2019 All work appearing in Gscene Ltd is 52 Craig’s Thoughts copyright. It is to be assumed that the copyright for material rests with the magazine unless otherwise stated on the 53 Wall’s Words page concerned. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in 53 Gay Socrates an electronic or other retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means, 54 Charlie Says electronic, mechanical, photocopying, FEATURES recording or otherwise without the prior 55 Hydes’ Hopes knowledge and consent of the publishers. -

Sparking a Steam Revolution: Examining the Evolution and Impact of Digital Distribution in Gaming

Sparking a Steam Revolution: Examining the Evolution and Impact of Digital Distribution in Gaming by Robert C. Hoile At this moment there’s a Renaissance taking place in games, in the breadth of genres and the range of emotional territory they cover. I’d hate to see this wither on the vine because the cultural conversation never caught up to what was going on. We need to be able to talk about art games and ‘indie’ games the ways we do about art and indie film. (Isbister xvii) The thought of a videogame Renaissance, as suggested by Katherine Isbister, is both appealing and reasonable, yet she uses the term Renaissance rather casually in her introduction to How Games Move Us (2016). She is right to assert that there is diversity in the genres being covered and invented and to point out the effectiveness of games to reach substantive emotional levels in players. As a revival of something in the past, a Renaissance signifies change based on revision, revitalization, and rediscovery. For this term to apply to games then, there would need to be a radical change based not necessarily on rediscovery of, but inspired/incited by something perceived to be from a better time. In this regard the videogame industry shows signs of being in a Renaissance. Videogame developers have been attempting to innovate and push the industry forward for years, yet people still widely regard classics, like Nintendo’s Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998), as the best games of all time. As with the infatuation with sequels in contemporary Hollywood cinema, game companies are often perceived as producing content only for the money while neglecting quality. -

Stockholm Cinema Studies 11

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Cinema Studies 11 Imagining Safe Space The Politics of Queer, Feminist and Lesbian Pornography Ingrid Ryberg This is a print on demand publication distributed by Stockholm University Library www.sub.su.se First issue printed by US-AB 2012 ©Ingrid Ryberg and Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis 2012 ISSN 1653-4859 ISBN 978-91-86071-83-7 Publisher: Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis, Stockholm Distributor: Stockholm University Library, Sweden Printed 2012 by US-AB Cover image: Still from Phone Fuck (Ingrid Ryberg, 2009) Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................... 13 Research aims and questions .................................................................................... 13 Queer, feminist and lesbian porn film culture: central debates.................................... 19 Feminism and/vs. pornography ............................................................................. 20 What is queer, feminist and lesbian pornography?................................................ 25 The sexualized public sphere................................................................................ 27 Interpretive community as a key concept and theoretical framework.......................... 30 Spectatorial practices and historical context.......................................................... 33 Porn studies .......................................................................................................... 35 Embodied -

Art Worlds for Art Games Edited

Loading… The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association Vol 7(11): 41-60 http://loading.gamestudies.ca An Art World for Artgames Felan Parker York University [email protected] Abstract Drawing together the insights of game studies, aesthetics, and the sociology of art, this article examines the legitimation of ‘artgames’ as a category of indie games with particularly high cultural and artistic status. Passage (PC, Mac, Linux, iOS, 2007) serves as a case study, demonstrating how a diverse range of factors and processes, including a conducive ‘opportunity space’, changes in independent game production, distribution, and reception, and the emergence of a critical discourse, collectively produce an assemblage or ‘art world’ (Baumann, 2007a; 2007b) that constitutes artgames as legitimate art. Author Keywords Artgames; legitimation; art world; indie games; critical discourse; authorship; Passage; Rohrer Introduction The seemingly meteoric rise to widespread recognition of ‘indie’ digital games in recent years is the product of a much longer process made up of many diverse elements. It is generally accepted as a given that indie games now play an important role in the industry and culture of digital games, but just over a decade ago there was no such category in popular discourse – independent game production went by other names (freeware, shareware, amateur, bedroom) and took place in insular, autonomous communities of practice focused on particular game-creation tools or genres, with their own distribution networks, audiences, and systems of evaluation, only occasionally connected with a larger marketplace. Even five years ago, the idea of indie games was still burgeoning and becoming stable, and it is the historical moment around 2007 that I will address in this article. -

And the Lgbt Plaque Went To

F AND THE LGBT R EE PLAQUE WENT TO …. QB Nottinghamshire’s Queer Bulletin May/June 2021 Number 120 In this issue The £50 note Gravity A postal library Queers Part Two Places to retire Beergardens Gardening at Sissinghurst A walking tour and other stuff From a short list of four, including The New Foresters has been an Nottingham Women’s Centre, the LGBT friendly venue continuously Flying Horse and the National Jus- since 1958. The pub has won tice Museum, the vote went to the many awards e.g. in 2018 for the New Foresters as the first building 2nd year in succession, it won in Nottingham to receive an LGBT the “Best Bar None” award and plaque. also the “Best Independent Ven- For those unfamiliar with the ue” award. LGBT history behind these four places, here’s a quick run down: The National Justice Museum has recently held several exhibi- tions with LGBT themes and helped organise the “Desire, Love, Identity” book of local LGBT mem- oirs. Its darker history was when it If you have any information, news, was a court which saw several gossip or libel or wish to comment prosecutions of gay men in pre- on anything in QB, please contact 1967 days. QB The Flying Horse was the main Notts LGBT+ Network gay bar in the 1950s and 1960s 35 Park Row and was apparently world famous They have regularly raised mon- Nottingham NG1 6EE and known as the “pansy’s par- ey for charities including Notts lour”. LGBT+ Network and Stonebridge or e-mail The Women’s Centre continues City Farm. -

Handmade 2.0: Women, DIY Networks and the Cultural Economy of Craft

Handmade 2.0: Women, DIY Networks and the Cultural Economy of Craft Jacqueline Wallace A Thesis in the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada June, 2014 © Jacqueline Wallace 2014 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Jacqueline Wallace Entitled: Handmade 2.0: Women, DIY Networks and the Cultural Economy of Craft and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Communication) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: _________________________________________________Chair Dr. Brian Gabrial _________________________________________________External Examiner Dr. R. Gajjala _________________________________________________External to Program Dr. N. Rantisi _________________________________________________Examiner Dr. J. Pidduck _________________________________________________Examiner Dr. K. Sawchuk _________________________________________________Thesis Supervisor Dr. M. Soar Approved by __________________________________________ Dr. Jeremy Stolow, Graduate Program Director June 11, 2014 __________________________________________ Professor J. Locke, Interim Dean Faculty of Arts and Science ii ABSTRACT Handmade 2.0: Women, DIY Networks and the Cultural Economy of Craft Jacqueline Wallace, PhD Concordia University, 2014 This dissertation is a feminist ethnography of the contemporary craft scene in North America. It examines do-it-yourself (DIY) networks of indie crafts as a significant cultural economy and site of women’s creative labour, moving beyond existing research, which has historically focused on craft as primarily associated with women’s domestic activity, or as a salon refusé subordinated to the fine arts, or affiliations with turn of the 20th century industrialization. -

Love Is GREAT Edition 1, March 2015

An LGBT guide Brought to you by for international media March 2015 Narberth Pembrokeshire, Wales visitbritain.com/media Contents Love is GREAT guide at a glance .................................................................................................................. 3 Love is GREAT – why? .................................................................................................................................... 4 Britain says ‘I do’ to marriage for same sex couples .............................................................................. 6 Plan your dream wedding! ............................................................................................................................. 7 The most romantic places to honeymoon in Britain ............................................................................. 10 10 restaurants for a romantic rendezvous ............................................................................................... 13 12 Countryside Hideaways ........................................................................................................................... 16 Nightlife: Britain’s fabulous LGBT clubs and bars ................................................................................. 20 25 year of Manchester and Brighton Prides .......................................................................................... 25 Shopping in Britain ....................................................................................................................................... -

VIDEO GAME SUBCULTURES Playing at the Periphery of Mainstream Culture Edited by Marco Benoît Carbone & Paolo Ruffino

ISSN 2280-7705 www.gamejournal.it Published by LUDICA Issue 03, 2014 – volume 1: JOURNAL (PEER-REVIEWED) VIDEO GAME SUBCULTURES Playing at the periphery of mainstream culture Edited by Marco Benoît Carbone & Paolo Ruffino GAME JOURNAL – Peer Reviewed Section Issue 03 – 2014 GAME Journal A PROJECT BY SUPERVISING EDITORS Antioco Floris (Università di Cagliari), Roy Menarini (Università di Bologna), Peppino Ortoleva (Università di Torino), Leonardo Quaresima (Università di Udine). EDITORS WITH THE PATRONAGE OF Marco Benoît Carbone (University College London), Giovanni Caruso (Università di Udine), Riccardo Fassone (Università di Torino), Gabriele Ferri (Indiana University), Adam Gallimore (University of Warwick), Ivan Girina (University of Warwick), Federico Giordano (Università per Stranieri di Perugia), Dipartimento di Storia, Beni Culturali e Territorio Valentina Paggiarin, Justin Pickard, Paolo Ruffino (Goldsmiths, University of London), Mauro Salvador (Università Cattolica, Milano), Marco Teti (Università di Ferrara). PARTNERS ADVISORY BOARD Espen Aarseth (IT University of Copenaghen), Matteo Bittanti (California College of the Arts), Jay David Bolter (Georgia Institute of Technology), Gordon C. Calleja (IT University of Copenaghen), Gianni Canova (IULM, Milano), Antonio Catolfi (Università per Stranieri di Perugia), Mia Consalvo (Ohio University), Patrick Coppock (Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia), Ruggero Eugeni (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano), Roy Menarini (Università di Bologna), Enrico Menduni (Università di