Article-P129.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modified Plate-Only Open-Door Laminoplasty Versus Laminectomy and Fusion for the Treatment of Cervical Stenotic Myelopathy

n Feature Article Modified Plate-only Open-door Laminoplasty Versus Laminectomy and Fusion for the Treatment of Cervical Stenotic Myelopathy LILI YANG, MD; YIFEI GU, MD; JUEQIAN SHI, MD; RUI GAO, MD; YANG LIU, MD; JUN LI, MD; WEN YUAN, MD, PHD abstract Full article available online at Healio.com/Orthopedics. Search: 20121217-23 The purpose of this study was to compare modified plate-only laminoplasty and lami- nectomy and fusion to confirm which of the 2 surgical modalities could achieve a better decompression outcome and whether a significant difference was found in postopera- tive complications. Clinical data were retrospectively reviewed for 141 patients with cervical stenotic myelopathy who underwent plate-only laminoplasty and laminectomy and fusion between November 2007 and June 2010. The extent of decompression was assessed by measuring the cross-sectional area of the dural sac and the distance of spinal cord drift at the 3 most narrowed levels on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Clinical outcomes and complications were also recorded and compared. Significant en- largement of the dural sac area and spinal cord drift was achieved and well maintained in both groups, but the extent of decompression was greater in patients who underwent Figure: T2-weighted magnetic resonance image laminectomy and fusion; however, a greater decompression did not seem to produce a showing the extent of decompression assessed by better clinical outcome. No significant difference was observed in Japanese Orthopaedic measuring the cross-sectional area of the dural sac Association and Nurick scores between the 2 groups. Patients who underwent plate-only (arrow). laminoplasty showed a better improvement in Neck Dysfunction Index and visual ana- log scale scores. -

Analysis of the Cervical Spine Alignment Following Laminoplasty and Laminectomy

Spinal Cord (1999) 37, 20± 24 ã 1999 International Medical Society of Paraplegia All rights reserved 1362 ± 4393/99 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/sc Analysis of the cervical spine alignment following laminoplasty and laminectomy Shunji Matsunaga1, Takashi Sakou1 and Kenji Nakanisi2 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Kagoshima University; 2Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Kagoshima University, Sakuragaoka, Kagoshima, Japan Very little detailed biomechanical examination of the alignment of the cervical spine following laminoplasty has been reported. We performed a comparative study regarding the buckling- type alignment that follows laminoplasty and laminectomy to know the mechanical changes in the alignment of the cervical spine. Lateral images of plain roentgenograms of the cervical spine were put into a computer and examined using a program we developed for analysis of the buckling-type alignment. Sixty-four patients who underwent laminoplasty and 37 patients who underwent laminectomy were reviewed retrospectively. The subjects comprised patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) and those with ossi®cation of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL). The postoperative observation period was 6 years and 7 months on average after laminectomy, and 5 years and 6 months on average following laminoplasty. Development of the buckling-type alignment was found in 33% of patients following laminectomy and only 6% after laminoplasty. Development of buckling-type alignment following laminoplasty appeared markedly less than following laminectomy in both CSM and OPLL patients. These results favor laminoplasty over laminectomy from the aspect of mechanics. Keywords: laminoplasty; laminectomy; buckling; kyphosis; swan-neck deformity Introduction In 1930, Eiselberg1 reported a case of postoperative of postoperative abnormal alignment from the aspect kyphosis of the spine following laminectomy from the of the presence or absence of buckling-type alignment. -

Differences Between Subtotal Corpectomy and Laminoplasty for Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy

Spinal Cord (2010) 48, 214–220 & 2010 International Spinal Cord Society All rights reserved 1362-4393/10 $32.00 www.nature.com/sc ORIGINAL ARTICLE Differences between subtotal corpectomy and laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy S Shibuya1, S Komatsubara1, S Oka2, Y Kanda1, N Arima1 and T Yamamoto1 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, School of Medicine, Kagawa University, Kagawa, Japan and 2Oka Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation Clinic, Kagawa, Japan Objective: This study aimed to obtain guidelines for choosing between subtotal corpectomy (SC) and laminoplasty (LP) by analysing the surgical outcomes, radiological changes and problems associated with each surgical modality. Study Design: A retrospective analysis of two interventional case series. Setting: Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Kagawa University, Japan. Methods: Subjects comprised 34 patients who underwent SC and 49 patients who underwent LP. SC was performed by high-speed drilling to remove vertebral bodies. Autologous strut bone grafting was used. LP was performed as an expansive open-door LP. The level of decompression was from C3 to C7. Clinical evaluations included recovery rate (RR), frequency of C5 root palsy after surgery, re-operation and axial pain. Radiographic assessments included sagittal cervical alignment and bone union. Results: Comparisons between the two groups showed no significant differences in age at surgery, preoperative factors, RR and frequency of C5 palsy. Progression of kyphotic changes, operation time and volumes of blood loss and blood transfusion were significantly greater in the SC (two- or three- level) group. Six patients in the SC group required additional surgery because of pseudoarthrosis, and four patients underwent re-operation because of adjacent level disc degeneration. -

Biomechanical Analysis of Posterior Ligaments of Cervical Spine and Laminoplasty

applied sciences Article Biomechanical Analysis of Posterior Ligaments of Cervical Spine and Laminoplasty Norihiro Nishida 1 , Muzammil Mumtaz 2, Sudharshan Tripathi 2, Amey Kelkar 2, Takashi Sakai 1 and Vijay K. Goel 2,* 1 Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, 1-1-1 Minami-Kogushi, Ube, Yamaguchi Prefecture 755-8505, Japan; [email protected] (N.N.); [email protected] (T.S.) 2 Engineering Center for Orthopaedic Research Excellence (E-CORE), Departments of Bioengineering and Orthopaedics, The University of Toledo, Toledo, OH 43606, USA; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (S.T.); [email protected] (A.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-(419)-530-8035 Abstract: Cervical laminoplasty is a valuable procedure for myelopathy but it is associated with complications such as increased kyphosis. The effect of ligament damage during cervical lamino- plasty on biomechanics is not well understood. We developed the C2–C7 cervical spine finite element model and simulated C3–C6 double-door laminoplasty. Three models were created (a) in- tact, (b) laminoplasty-pre (model assuming that the ligamentum flavum (LF) between C3–C6 was preserved during surgery), and (c) laminoplasty-res (model assuming that the LF between C3–C6 was resected during surgery). The models were subjected to physiological loading, and the range of motion (ROM), intervertebral nucleus stress, and facet contact forces were analyzed under flex- ion/extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation. The maximum change in ROM was observed Citation: Nishida, N.; Mumtaz, M.; under flexion motion. Under flexion, ROM in the laminoplasty-pre model increased by 100.2%, Tripathi, S.; Kelkar, A.; Sakai, T.; Goel, 111.8%, and 98.6% compared to the intact model at C3–C4, C4–C5, and C5–C6, respectively. -

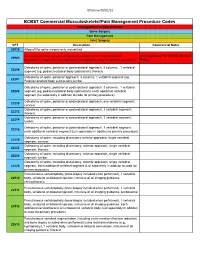

Commercial MSK Procedure Code List Effective 09.01.21.Xlsx

Effective 09/01/21 BCBST Commercial Musculoskeletal/Pain Management Procedure Codes Investigational or Non-Covered Spine Surgery Pain Management Joint Surgery CPT Description Commercial Notes 20930 Allograft for spine surgery only morselized Computer-assisted surgical navigational procedure for musculoskeletal Investigational Per BCBST Medical 20985 procedures, image-less (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Policy Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral 22206 segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral body subtraction); thoracic Osteotomy of spine, posterior approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg. 22207 Pedicle/vertebral body subtraction);lumbar Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral 22208 segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral body subtraction); each additional vertebral segment (list separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, one vertebral segment; 22210 cervical Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 1 vertebral segment; 22212 thoracic Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 1 vertebral segment; 22214 lumbar Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 1 vertebral segment; 22216 each additional vertebral segment (List separately in addition to primary procedure) Osteotomy of spine, including discectomy anterior approach, single vertebral 22220 segment; cervical Osteotomy of spine, including discectomy, anterior approach, single -

Cervical Laminoplasty - Principles, Surgical Methods, Results, and Issues

Open Access Austin Journal of Surgery Special Article – Cervical Surgery Cervical Laminoplasty - Principles, Surgical Methods, Results, and Issues Hirabayashi S*, Kitagawa T and Kawano H Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Teikyo University Abstract Hospital, Japan Cervical laminoplasty (CL) is one of the surgical methods via posterior *Corresponding author: Hirabayashi S, Department approach for treating patients with cervical myelopathy. The main purpose of of Orthopaedic Surgery, Teikyo University Hospital, CL is to decompress the cervical spinal cord by widening the narrowed spinal Japan canal, combined with preserving the posterior anatomical structures to the degree possible. At present, these surgical methods are broadly divided into Received: November 23, 2017; Accepted: December two types from the viewpoints of the site of osteotomy: Double-door type 12, 2017; Published: December 19, 2017 (DDL) and Open-door type (ODL). Various materials are used to maintain the enlarged spinal canal such as autogeneous bone (spinous process, iliac bone), hydroxyapatite spacer, titanium plate and screw, thread, and so on. Although the surgical methods and techniques of CL and the methods of assessment are various, recovery rates have been reported to be about 60~70%. The main influential factors on the surgical results are the age of the patients, the duration of the diseases, accompanying injuries to the cervical spine, and the neurological findings just before surgery. CL can be safely performed and stable surgical results maintained for a long period; more than 10 years. However, patients with large prominence-type of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) and severe kyphotic alignment of the cervical spine are relatively contraindicated because of possibility of inadequate posterior shift of the spinal cord. -

2018 Nuvasive® Reimbursement Guide

2018 NuVasive® Reimbursement Guide Assisting physicians and facilities in accurate billing for NuVasive implants and instrumentation systems. 2018 Reimbursement Guide Contents I. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................2 II. Physician Coding and Payment ......................................................................................................................................2 Fusion Facilitating Technologies ............................................................................................................................................. 2 NVM5® Intraoperative Monitoring System ........................................................................................................................... 12 III. Hospital Inpatient Coding and Payment ....................................................................................................................13 NuVasive® Technology ..........................................................................................................................................................13 Non-Medicare Reimbursement ............................................................................................................................................13 IV. Outpatient Facility Coding and Payment ..................................................................................................................14 Hospital Outpatient -

Outcomes of Cervical Spine Surgery in Teaching and Non-Teaching Hospitals Steven J

SPINE Volume 38, Number 13, pp 1089–1096 ©2013, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins CERVICAL SPINE Outcomes of Cervical Spine Surgery in Teaching and Non-Teaching Hospitals Steven J. Fineberg , MD , * Matthew Oglesby , BA , * Alpesh A. Patel , MD , † Miguel A. Pelton , BS , ‡ and Kern Singh , MD * 65 years or more (odds ratio = 3.0) and multiple comorbidities. Study Design. Retrospective national database analysis. Teaching status was not a signifi cant predictor of mortality Objective. A national population-based database was analyzed to ( P = 0.07). characterize cervical spine procedures performed at teaching and Conclusion. Patients treated in teaching hospitals for cervical spine nonteaching hospitals with regards to patient demographics, clinical surgery demonstrated longer hospitalizations, increased costs, and outcomes/complications, resource use, and costs. mortality compared with patients treated in nonteaching hospitals. Summary of Background Data. There are mixed reports in the Incidences of postoperative complications were identifi ed to be literature regarding the quality and costs of health care provided higher in teaching hospitals. Possible explanations for these fi ndings by teaching hospitals in the United States. However, outcomes of are an increased complexity of procedures performed at teaching cervical spine surgery based upon teaching status remains largely hospitals. Older age and presence of comorbidities were more unknown. signifi cant predictors of inhospital mortality than teaching status. Methods. Data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample were Future studies should identify long-term complications and costs obtained from 2002–2009. Patients undergoing elective anterior or beyond an inpatient setting to assess if differences extend beyond posterior cervical fusion, or posterior cervical decompression (i.e. -

Cervical Laminoplasty Michael P

The Spine Journal 6 (2006) 274S–281S Cervical laminoplasty Michael P. Steinmetz, MD, Daniel K. Resnick, MD* Department of Neurosurgery, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, K4/834 Clinical Science Center, 600 Highland Ave., Madison, WI 53792, USA Abstract Laminoplasty was developed to treat multilevel pathology of the cervical spine, namely ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament and cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Laminoplasty was pop- ularized in the 1980s, and since then many variations on the theme have been developed. All are similar in that they expand the cervical canal while leaving the protective dorsal elements in place. Advocates claim that this prevents the formation of the ‘‘postlaminectomy’’ membrane, maintains spinal alignment, and should aid in maintaining cervical range of motion. The aforementioned are all potential shortcomings of laminectomy or laminectomy and fusion. The procedure has proven to be essentially equal to other cervical decompressive procedures in the neutral or lordotic spine, and outcome has been shown to be durable. Ó 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Laminoplasty; Cervical spine; Laminectomy; Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament; Cervical spon- dylotic myelopathy; Myelopathy; Cervical stenosis Introduction potentially reduce the incidence of postoperative instability. Cervical motion is theoretically preserved. In 1973, Oyama Cervical laminectomy has long been the treatment for et al. introduced a Z-plasty of the cervical spine [1]. This multilevel cervical spondylosis. It permits adequate decom- procedure allowed decompression, while the retained lam- pression of the cervical spinal cord and is safe and easily inae provided support and prevented invasion of the postla- performed. Potential adverse outcomes after cervical lami- minectomy membrane. -

Open Door Laminoplasty: Creation of a New Vertebral Arch

Open Door Laminoplasty: Creation Of A New Vertebral Arch Monica Lara-Almunia and Javier Hernandez-Vicente Int J Spine Surg 2017, 11 (1) doi: https://doi.org/10.14444/4006 http://ijssurgery.com/content/11/1/6 This information is current as of September 26, 2021. Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://ijssurgery.com/alerts The International Journal Downloadedof Spine Surgery from http://ijssurgery.com/ by guest on September 26, 2021 2397 Waterbury Circle, Suite 1, Aurora, IL 60504, Phone: +1-630-375-1432 © 2017 ISASS. All Rights Reserved. Open Door Laminoplasty: Creation Of A New Vertebral Arch Monica Lara-Almunia, MD,1 Javier Hernandez-Vicente, MD2 1Department of Neurosurgery, Son Espases University Hospital, Mallorca, Spain, 2Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital of Salamanca, Sala- manca, Spain Abstract Background We describe the carrying out of our open door laminoplasty technique by reproducing a posterior vertebral arch us- ing a local originating autologous bony graft and titanium plates. Methods We designed a prospective study and present our first 16 patients. The clinical results were evaluated with the JOA score, Nurick scale and the VAS. The functional and radiological evaluation was performed with radiographs, CT and MRI, and the measurements of the dimensions of the spinal canal were carried out with the MIPAV pro- gramme ( Johns Hopkins University). All the variables were statistically analysed by means of SPSS23.0. Results After following up the cases for two years, the clinical evaluation showed, amongst other findings, a 75% improve- ment in the JOA score, while the radiological controls showed an appropriate range of motion (ROM) along with the stability of the construction. -

Postoperative Spinal CT: What the L EARNIN

This copy is for personal use only. To order printed copies, contact [email protected] 1840 Postoperative Spinal CT: What the Radiologist Needs to Know SPINE IMAGING Nevil Ghodasara, MD Paul H. Yi, MD During the past 2 decades, the number of spinal surgeries per- Karen Clark, MD formed annually has been steadily increasing, and these procedures Elliot K. Fishman, MD are being accompanied by a growing number of postoperative Mazda Farshad, MD, MPH imaging studies to interpret. CT is accurate for identifying the loca- Jan Fritz, MD tion and integrity of implants, assessing the success of decompres- sion and intervertebral arthrodesis procedures, and detecting and Abbreviations: ACDF = anterior cervical dis- characterizing related complications. Although postoperative spinal cectomy and fusion, BMP = bone morphoge- CT is often limited owing to artifacts caused by metallic implants, netic protein parameter optimization and advanced metal artifact reduction RadioGraphics 2019; 39:1840–1861 techniques, including iterative reconstruction and monoenergetic https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2019190050 extrapolation methods, can be used to reduce metal artifact sever- Content Codes: ity and improve image quality substantially. Commonly used and From the Russell H. Morgan Department recently available spinal implants and prostheses include screws and of Radiology and Radiologic Science (N.G., wires, static and extendable rods, bone grafts and biologic materi- P.H.Y., K.C.), Sections of Body CT (E.K.F.) als, interbody cages, and intervertebral disk prostheses. CT assess- and Musculoskeletal Radiology (J.F.), Johns Hopkins Hospital, 601 N Caroline St, Room ment and the spectrum of complications that can occur after spinal 3014, Baltimore, MD 21287; and Spine Divi- surgery and intervertebral arthroplasty include those related to the sion, Department of Orthopedics, Balgrist Uni- versity Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland position and integrity of implants and prostheses, adjacent segment (M.F.). -

Curriculum Vitae Charles Cannon Edwards II, M.D

Curriculum Vitae Charles Cannon Edwards II, M.D. Revised October 2020 Education: Fellow, Spine Surgery, Maryland Spine Center Baltimore, Maryland, August 2002 – Dec. 2002 Fellow, Spine Surgery, Washington University St. Louis, Missouri, August 2001 – July 2002 Resident, Orthopaedic Surgery, Emory University Atlanta, Georgia, July 1996- June 2001 M.D., University of Maryland, School of Medicine Baltimore, Maryland, September 1992- May 1996 B.A., Chemistry with Honors in Engineering Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia August 1988- June 1992 Honors/Awards: Residency: • First Place, Resident Paper Competition, Georgia Orthopaedic Society Annual Meeting 2000, Laminoplasty versus Laminectomy and Fusion for the Management of Cervical Myelopathy, An Independent Matched Cohort Analysis • Mario Boni Award for the Outstanding Paper, European Cervical Spine Research Society Annual Meeting, London, England, June, 2000: Laminoplasty versus Laminectomy and Fusion … • Best Paper, Emory Resident Research Day 2000: Laminoplasty versus Laminectomy and Fusion … • Best Resident/ Fellow Paper, Clinical Orthopaedic Society Annual Meeting 1999, T- Saw Laminoplasty for the Management of Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy: Clinical and Radiographic Outcome. • Best Paper, Emory Resident Research Day 1999: T-Saw Laminoplasty … • Elected Representative, Resident- Faculty Advisory Panel: 1997-1998, 1998-1999, 1999-2000 • OITE 1999: 95th percentile for year in training • OITE 1998: 94th percentile for year in training Medical School: * Alpha Omega Alpha