Cervical Laminoplasty Michael P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modified Plate-Only Open-Door Laminoplasty Versus Laminectomy and Fusion for the Treatment of Cervical Stenotic Myelopathy

n Feature Article Modified Plate-only Open-door Laminoplasty Versus Laminectomy and Fusion for the Treatment of Cervical Stenotic Myelopathy LILI YANG, MD; YIFEI GU, MD; JUEQIAN SHI, MD; RUI GAO, MD; YANG LIU, MD; JUN LI, MD; WEN YUAN, MD, PHD abstract Full article available online at Healio.com/Orthopedics. Search: 20121217-23 The purpose of this study was to compare modified plate-only laminoplasty and lami- nectomy and fusion to confirm which of the 2 surgical modalities could achieve a better decompression outcome and whether a significant difference was found in postopera- tive complications. Clinical data were retrospectively reviewed for 141 patients with cervical stenotic myelopathy who underwent plate-only laminoplasty and laminectomy and fusion between November 2007 and June 2010. The extent of decompression was assessed by measuring the cross-sectional area of the dural sac and the distance of spinal cord drift at the 3 most narrowed levels on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Clinical outcomes and complications were also recorded and compared. Significant en- largement of the dural sac area and spinal cord drift was achieved and well maintained in both groups, but the extent of decompression was greater in patients who underwent Figure: T2-weighted magnetic resonance image laminectomy and fusion; however, a greater decompression did not seem to produce a showing the extent of decompression assessed by better clinical outcome. No significant difference was observed in Japanese Orthopaedic measuring the cross-sectional area of the dural sac Association and Nurick scores between the 2 groups. Patients who underwent plate-only (arrow). laminoplasty showed a better improvement in Neck Dysfunction Index and visual ana- log scale scores. -

Anterior Reconstruction Techniques for Cervical Spine Deformity

Neurospine 2020;17(3):534-542. Neurospine https://doi.org/10.14245/ns.2040380.190 pISSN 2586-6583 eISSN 2586-6591 Review Article Anterior Reconstruction Techniques Corresponding Author for Cervical Spine Deformity Samuel K. Cho 1,2 1 1 1 https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7511-2486 Murray Echt , Christopher Mikhail , Steven J. Girdler , Samuel K. Cho 1Department of Orthopedics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA Department of Orthopaedics, Icahn 2 Department of Neurological Surgery, Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 425 NY, USA West 59th Street, 5th Floor, New York, NY, USA E-mail: [email protected] Cervical spine deformity is an uncommon yet severely debilitating condition marked by its heterogeneity. Anterior reconstruction techniques represent a familiar approach with a range Received: June 24, 2020 of invasiveness and correction potential—including global or focal realignment in the sagit- Revised: August 5, 2020 tal and coronal planes. Meticulous preoperative planning is required to improve or prevent Accepted: August 17, 2020 neurologic deterioration and obtain satisfactory global spinal harmony. The ability to per- form anterior only reconstruction requires mobility of the opposite column to achieve cor- rection, unless a combined approach is planned. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion has limited focal correction, but when applied over multiple levels there is a cumulative ef- fect with a correction of approximately 6° per level. Partial or complete corpectomy has the ability to correct sagittal deformity as well as decompress the spinal canal when there is an- terior compression behind the vertebral body. -

2019 Spine Coding Basics

2019 Spine Coding Basics Presenter: Kerri Larson, CPC Directory of Coding and Audit Services 2019 Spine Surgery 01 Spine Surgery Terminology & Anatomy 02 Spine Procedures 03 Case Study 04 Diagnosis 05 Q & A Spine Surgery Terminology & Anatomy Spine Surgery Terminology & Anatomy Term Definition Arthrodesis Fusion, or permanent joining, of a joint, or point of union of two musculoskeletal structures, such as two bones Surgical procedure that replaces missing bone with material from the patient's own body, or from an artificial, synthetic, or Bone grafting natural substitute Corpectomy Surgical excision of the main body of a vertebra, one of the interlocking bones of the back. Cerebrospinal The protective body fluid present in the dura, the membrane covering the brain and spinal cord fluid or CSF Decompression A procedure to remove pressure on a structure. Diskectomy, Surgical removal of all or a part of an intervertebral disc. discectomy Dura Outermost of the three layers that surround the brain and spinal cord. Electrode array Device that contains multiple plates or electrodes. Electronic pulse A device that produces low voltage electrical pulses, with a regular or intermittent waveform, that creates a mild tingling or generator or massaging sensation that stimulates the nerve pathways neurostimulator Spine Surgery Terminology & Anatomy Term Definition The space that surrounds the dura, which is the outermost layer of membrane that surrounds the spinal canal. The epidural space houses the Epidural space spinal nerve roots, blood and lymphatic vessels, and fatty tissues . Present inside the skull but outside the dura mater, which is the thick, outermost membrane covering the brain or within the spine but outside Extradural the dural sac enclosing the spinal cord, nerve roots and spinal fluid. -

Analysis of the Cervical Spine Alignment Following Laminoplasty and Laminectomy

Spinal Cord (1999) 37, 20± 24 ã 1999 International Medical Society of Paraplegia All rights reserved 1362 ± 4393/99 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/sc Analysis of the cervical spine alignment following laminoplasty and laminectomy Shunji Matsunaga1, Takashi Sakou1 and Kenji Nakanisi2 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Kagoshima University; 2Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Kagoshima University, Sakuragaoka, Kagoshima, Japan Very little detailed biomechanical examination of the alignment of the cervical spine following laminoplasty has been reported. We performed a comparative study regarding the buckling- type alignment that follows laminoplasty and laminectomy to know the mechanical changes in the alignment of the cervical spine. Lateral images of plain roentgenograms of the cervical spine were put into a computer and examined using a program we developed for analysis of the buckling-type alignment. Sixty-four patients who underwent laminoplasty and 37 patients who underwent laminectomy were reviewed retrospectively. The subjects comprised patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) and those with ossi®cation of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL). The postoperative observation period was 6 years and 7 months on average after laminectomy, and 5 years and 6 months on average following laminoplasty. Development of the buckling-type alignment was found in 33% of patients following laminectomy and only 6% after laminoplasty. Development of buckling-type alignment following laminoplasty appeared markedly less than following laminectomy in both CSM and OPLL patients. These results favor laminoplasty over laminectomy from the aspect of mechanics. Keywords: laminoplasty; laminectomy; buckling; kyphosis; swan-neck deformity Introduction In 1930, Eiselberg1 reported a case of postoperative of postoperative abnormal alignment from the aspect kyphosis of the spine following laminectomy from the of the presence or absence of buckling-type alignment. -

Lumbar Laminectomy

Patient Education Lumbar Laminectomy Description The spine consists of five separate divisions: cervical (seven vertebrae), thoracic (12 vertebrae), lumbar (five vertebrae), the sacrum, and the coccyx. Each vertebra, interlocks with the segment above and below it through the superior and inferior articular processes. Between each vertebra is an intervertebral disc that provides cushioning for the spine. The lamina and pedicle, along with the vertebral body, provide the borders that create the spinal canal, which the spinal cord runs through to transmit nerve signals. There are several different scenarios or conditions that may produce symptoms that would lead your physician to further Medical Illustration © 2016 Nucleus Medical Art, Inc. investigate, and possibly recommend this surgery. Stenosis causing Radicular Pain Spinal stenosis is the narrowing of the articular spaces within the spine; this may impinge on the nerves or the spinal cord. This is a degenerative process and may eventually lead to further changes on the spine over time. Radicular symptoms are pain, numbness, weakness, tingling, etc., that radiate along a specific nerve root (or dermatome) to other parts of the body outside of the spine. Surgical correction of this problem may include a minimally invasive decompression (shaving bone away to create more space around the nerve), often referred to as laminectomy (removing part or all of the lamina in order to provide more space and relieve impingement). In some cases, movement of one vertebrae slipping against another (spondylolisthesis), may require a vertebral fusion. This may be performed open vs. minimally invasive. Disc Herniation Herniation of the intervertebral disc may be due to an acute traumatic incident. -

Modern Advances in Joint Replacement and Rapid Recovery

Modern Advances in Joint Replacement and Rapid Recovery UCSF Osher Mini-Med School Lecture Series Jeffrey Barry, M.D. Assistant Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery Division of Adult Reconstruction University of California, San Francisco Disclosures . No relevant disclosures to this talk About Me . Bay Area Native . UCSF - U Can Stay Forever Outline . Burden of Disease and Epidemiology . The Basics of Hip and Knee Replacement . What’s improving over the last decade - Longevity - Pain Management - Hospital Stay - Thromboembolism prophylaxis - Risk Reduction Question What is the most common inpatient surgery performed in the US? 1. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty 2. Total hip replacement 3. Lumbar Laminectomy 4. Appendectomy 5. Total knee replacement Burden of Disease . Arthritis = most common cause of disability in the US . 22.7% of adults have doctor-diagnosed arthritis - 43.2% of patients with arthritis report activity limitations due to disease . By 2030: - 3.5 million TKA (673%) - 570,000 THA (174%) . Curve updated 2014 – just as predicted! Causes of Increased Utilization . Aging Population . Patients receiving arthroplasty at a younger age - Improvements in technology - Obesity Why Replace a Joint? Arthritis arthro – joint itis – inflammation What is Arthritis – Disease of Cartilage . Cartilage Degeneration - Pain - Limp - Swelling - Loss of range of motion - Eventual deformity Arthritis Affects on Your Life • Quality of Life • Independence • Movement, Walking, Exercise • Self-image • Self-esteem • Family Life • Sleep • Everything and Everybody Causes of Arthritis . Osteoarthritis - “wear and tear” . Inflammatory arthritis . Trauma, old fractures . Infection . Osteonecrosis - “lack of oxygen to the bone” . Childhood/ developmental disease Diagnosis . Clinical Symptoms + Radiographic . Radiographs – Standing or Weight bearing! . MRI is RARELY needed!!! - Expensive - Brings in other issues - Unnecessary treatment - Unnecessary explanations Knee Arthritis . -

Two-Level Cervical Corpectomy—Long-Term Follow-Up Reveals the High Rate of Material Failure in Patients, Who Received an Anterior Approach Only

Neurosurgical Review (2019) 42:511–518 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-018-0993-6 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Two-level cervical corpectomy—long-term follow-up reveals the high rate of material failure in patients, who received an anterior approach only Simon Heinrich Bayerl1 & Florian Pöhlmann1 & Tobias Finger1 & Vincent Prinz1 & Peter Vajkoczy 1 Received: 25 August 2017 /Revised: 20 November 2017 /Accepted: 5 December 2017 /Published online: 18 June 2018 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract In contrast to a one-level cervical corpectomy, a multilevel corpectomy without posterior fusion is accompanied by a high material failure rate. So far, the adequate surgical technique for patients, who receive a two-level corpectomy, remains to be elucidated. The aim of this study was to determine the long-term clinical outcome of patients with cervical myelopathy, who underwent a two-level corpectomy. Outcome parameters of 21 patients, who received a two-level cervical corpectomy, were retrospectively analyzed concerning reoperations and outcome scores (VAS, Neck Disability Index (NDI), Nurick scale, mod- ified Japanese Orthopaedic Association score (mJOAS), Short Form 36-item Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36)). The failure rate was determined using postoperative radiographs. The choice over the surgical procedures was exercised by every surgeon individually. Therefore, a distinction between two groups was possible: (1) anterior group (ANT group) with a two-level corpectomy and a cervical plate, (2) anterior/posterior group (A/P group) with two-level corpectomy, cervical plate, and addi- tional posterior fusion. Both groups benefitted from surgery concerning pain, disability, and myelopathy. While all patients of the A/P group showed no postoperative instability, one third of the patients of the ANT group exhibited instability and clinical deterioration. -

The Need for Structural Allograft Biomechanical Guidelines

8 The Need for Structural Allograft Biomechanical Guidelines Satoshi Kawaguchi, MD Robert A. Hart, MD Abstract Because of their osteoconductive properties, structural bone allografts retain a theoretic advantage in biologic performance compared with artifi cial interbody fusion devices and endoprostheses. Current regulations have addressed the risks of disease transmission and tissue contamination, but comparatively few guidelines exist regarding donor eligibility and bone processing issues with a potential effect on the mechanical integrity of structural allograft bone. The lack of guidelines appears to have led to variation among allograft providers in terms of processing and donor screening regarding issues with recognized mechanical effects. Given the relative lack of data on which to base reasonable screening standards, a basic biomechanical evaluation was performed on one source of structural bone allograft, the femoral ring. Of the tested parameters, the minimum and maximum cortical wall thicknesses of femoral ring allograft were most strongly correlated with the axial compressive load to failure of the graft, suggesting that cortical wall thickness may be a useful screening tool for compressive resistance expected from fresh cortical bone allograft. Development of further biomechanical and clinical data to direct standard development appears warranted. Instr Course Lect 2015;64:87–93. Surgical implantation of structural al- form with limited anatomic modifi - by the US FDA as well as through vol- lograft bone continues to increase de- cations, modern tissue processing in- untary participation with the American spite advances in modern alternatives cludes preparations of amalgams of Association of Tissue Banks (AATB). to allograft, including spine interbody allograft bone tissue of specifi c shapes Guidelines for allograft bone products fusion devices and peripheral joint en- and sizes to suit specifi c surgical needs. -

Subtalar Joint Version 1.0 Effective June 15, 2021

CLINICAL GUIDELINES CMM-407: Arthroscopy: Subtalar Joint Version 1.0 Effective June 15, 2021 Clinical guidelines for medical necessity review of Comprehensive Musculoskeletal Management Services. © 2021 eviCore healthcare. All rights reserved. Comprehensive Musculoskeletal Management Guidelines V1.0 CMM-407: Arthroscopy: Subtalar Joint Definitions 3 General Guidelines 3 Indications 4 Non-Indications 5 Procedure (CPT®) Codes 5 References 6 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ ©2021 eviCore healthcare. All Rights Reserved. Page 2 of 6 400 Buckwalter Place Boulevard, Bluffton, SC 29910 (800) 918-8924 www.eviCore.com Comprehensive Musculoskeletal Management Guidelines V1.0 Definitions Red flags indicate comorbidities that require urgent/emergent diagnostic imaging and/or referral for definitive therapy. Clinically meaningful improvement is defined as at least 50% improvement noted on global assessment. General Guidelines Either of the following are considered red flag conditions for subtalar joint arthroscopy: Post-reduction evaluation and management of the subtalar dislocation Septic arthritis in the subtalar joint Although imaging may be normal, prior to subtalar joint arthroscopy, radiographic imaging should be performed and include both of the following: Plain X-rays with one or more views (anteroposterior, lateral, axial, and/or Broden’s) to confirm and differentiate any of the following: Degenerative joint changes Loose bodies Osteochondral lesions Impingement -

Lumbar Laminectomy Or Laminotomy

Patient Instructions: Lumbar Laminectomy or Laminotomy Surgical Technique A lumbar laminectomy or laminotomy is a surgical approach performed from the back of the lumbar spine. It is usually done through an incision in the middle of the back. Using minimally invasive techniques a small window of bone is drilled in the lamina to allow the surgeon to unpinch the underlying nerves (laminotomy), or in more severe cases the bone is removed completely on both sides to allow nerves on both sides of the spinal canal to be decompressed (laminectomy). It is done using an operating microscope and microsurgical technique. It is used to treat spinal stenosis or lateral recess stenosis and alleviate the pain and/or numbness that occurs in a patients lower back or legs. It can many times be performed on an outpatient basis without the need for an overnight stay in a hospital. Before Surgery • Seven days prior to surgery, please do not take any anti-inflammatory NSAID medications (Celebrex, Ibuprofen, Aleve, Naprosyn, Advil, etc.) as this could prolong your bleeding time during surgery. • Do not eat or drink anything after midnight the day before surgery. This means nothing to drink the morning of surgery except you may take your normal medication with a sip of water if needed. This includes your blood pressure medicine, which in general should be taken. Consult your surgeon or primary care doctor regarding insulin if you take it. • Please do not be late to check in on the day of surgery or it may be cancelled. • Please bring your preoperative folder with you to the surgery and have it when you check in. -

In Patients with End-Stage Ankle Arthritis, How Does Total Ankle Arthroplasty Compared to Arthrodesis Affect Ankle Pain and Function?

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons Physician's Assistant Program Capstones School of Health Sciences 4-1-2020 In Patients with End-Stage Ankle Arthritis, How Does Total Ankle Arthroplasty Compared to Arthrodesis Affect Ankle Pain and Function? Zachary Whipple University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/pa-capstones Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Whipple, Zachary, "In Patients with End-Stage Ankle Arthritis, How Does Total Ankle Arthroplasty Compared to Arthrodesis Affect Ankle Pain and Function?" (2020). Physician's Assistant Program Capstones. 84. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/pa-capstones/84 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Health Sciences at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physician's Assistant Program Capstones by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In Patients with End-Stage Ankle Arthritis, How Does Total Ankle Arthroplasty Compared to Arthrodesis Affect Ankle Pain and Function? By Zachary Whipple Capstone Project Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Physician Assistant Education of the University of the Pacific in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF PHYSICIAN ASSISTANT STUDIES April 2020 Introduction End-stage ankle arthritis is a debilitating degenerative disease commonly located at the tibiotalar joint. The prevalence of symptomatic arthritis is about nine times lower than the rates associated with those of the knee or hip.1 Though less common than knee and hip arthritis, the US estimates greater than 50,000 new cases are reported each year.2 The most common etiology of ankle arthritis is post-traumatic pathology. -

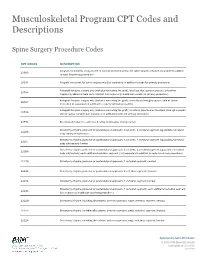

Musculoskeletal Program CPT Codes and Descriptions

Musculoskeletal Program CPT Codes and Descriptions Spine Surgery Procedure Codes CPT CODES DESCRIPTION Allograft, morselized, or placement of osteopromotive material, for spine surgery only (List separately in addition 20930 to code for primary procedure) 20931 Allograft, structural, for spine surgery only (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); local (eg, ribs, spinous process, or laminar 20936 fragments) obtained from same incision (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); morselized (through separate skin or fascial 20937 incision) (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); structural, bicortical or tricortical (through separate 20938 skin or fascial incision) (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) 20974 Electrical stimulation to aid bone healing; noninvasive (nonoperative) Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22206 body subtraction); thoracic Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22207 body subtraction); lumbar Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22208 body subtraction); each additional vertebral segment (List separately in addition to code for