British Alterations to the Palace-Complex of Shahj

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Administrative Tribunal Principal Bench, New Delhi. OA

1 Central Administrative Tribunal Principal Bench, New Delhi. OA-568/2013 New Delhi this the 11th day of May, 2016 HON’BLE MRS. JASMINE AHMED, MEMBER (J) Sh. Deepak Mohan Technical Officer- C DTRL, Metcalfe House, Delhi-110 054. ... Applicant (By Advocates: Sh. Anil Srivastava) Versus. 1. Union of India Through Secretary Ministry of Defence South Block, New Delhi- 110 001 2. DRDO (Defence Research and Development Organisation) Research and Development A Block, DRDO Bhawan New Delhi- 110 011 3. Joint Director (Personnel) (TC) Directorate of Personnel Research and Development A Block, DRDO Bhawan New Delhi- 110 011 4. Director DTRL (Defence Terrain Research Laboratory) Metcalfe House New Delhi- 110 054 ... Respondents ORDER (ORAL) Hon’ble Mrs. Jasmine Ahmed, Member (J) Vide order dated 05.02.2013, the applicant has been transferred from DTRL, Delhi to Dte. of Planning and Coordination, 2 DRDO, HQ in public interest. Learned counsel for applicant submits that the impugned order has been issued not in the interest of administration or exigency of service but for extraneous reasons and in colourable exercise of power by the concerned authority, particularly for the reason that the applicant did not accept and put his signature on the inventory, placed on record as A-7, without doing verification. He also alleges malafide against said respondent No.4. Accordingly on 15.02.2013, while notices were issued status quo with regard to posting of the applicant was directed to be maintained by the respondents. Applicant is enjoying the said interim order in his favour for more than three years. 2. -

Guards at the Taj by Rajiv Joseph

by Rajiv Joseph Guards at the Taj Registered Charity: 270080 Education Pack 2 Introduction focusing on new writing, ensemble work and theatre productions based on historical and The resources, research and information in real life figures. this study pack are intended to enhance your understanding of Guards at the Taj by Guards at the Taj tackles the challenges of Rajiv Joseph and to provide you with the researching, presenting and understanding materials to assist students in both the social, historical and political issues in an practical study of this text and in gaining a accessible and creative way. The play will GUARDS AT deeper understanding of this exciting new provoke students to ask pertinent questions, play. think critically, and develop perspective and judgement. This includes context (both political and theatrical), production photographs, Please note that this Education Pack includes discussion points and exercises that have key plot details about the play. The Classroom been devised to unpack the play’s themes and Exercises are most suitable for students who stylistic devices. have watched (or read) the play. THE TAJ In line with the national curriculum, Guards If you have any questions please don’t at the Taj would be a suitable live theatre hesitate to get in touch with Amanda production for analysis. It will also provide Castro on 0208 743 3584 or at Cross-Curicular: Drama and Theatre Studies, English an invaluable resource for students who are [email protected]. Literature, History, Politics, PSHE Key Stages -

A Case Study of Local Markets in Delhi

. CENTRE FOR NEW ECONOMICS STUDIES (CNES) Governing Dynamics of Informal Markets: A Case Study of Local Markets in Delhi. Principal Investigator1: Deepanshu Mohan Assistant Professor of Economics & Executive Director, Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES). O.P.Jindal Global University. Email id: [email protected] Co-Investigator: Richa Sekhani Senior Research Analyst, Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES),O.P.Jindal Global University. Email id: [email protected] 1 We would like to acknowledge the effort and amazing research provided by Sanjana Medipally, Shivkrit Rai, Raghu Vinayak, Atharva Deshmukh, Vaidik Dalal, Yunha Sangha, Ananya who worked as Research Assistants on the Project. Contents 1. Introduction 4 1.1 Significance: Choosing Delhi as a case study for studying informal markets ……. 6 2. A Brief Literature Review on Understanding the Notion of “Informality”: origin and debates 6 3. Scope of the study and objectives 9 3.1 Capturing samples of oral count(s) from merchants/vendors operating in targeted informal markets ………………………………………………………………………. 9 3.2 Gauging the Supply-Chain Dynamics of consumer baskets available in these markets… 9 3.3 Legality and Regulatory aspect of these markets and the “soft” relationship shared with the state ………………………………………………………………………….... 10 3.4 Understand to what extent bargaining power (in a buyer-seller framework) acts as an additional information variable in the price determination of a given basket of goods? ..10 4. Methodology 11 Figure 1: Overview of the zonal areas of the markets used in Delhi …………………... 12 Table 1: Number of interviews and product basket covered for the study …………….. 13 5. Introduction to the selected markets in Delhi 15 Figure 2: Overview of the strategic Dilli Haat location from INA metro Station ……... -

Directory of Institutions and Resource Persons in Disaster Management Content

DIRECTORY OF INSTITUTIONS AND RESOURCE PERSONS IN DISASTER MANAGEMENT CONTENT S. No. Topics Page No. 1. Preface 3 2. Forew ord 4 3. Prime Minister’s Office, Govt. of India 5 4. Cabinet Secretariat 5 5. Central Ministries and Departments of Government of India 6-18 6. National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) 19 -20 7. DM Division, Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India 21 8. National Institute of Disaster Management (NIDM) 22-24 9. National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) 25 -26 10. Principal Secretaries / Secretaries (Disaster Management) or Relief 27 -31 Commissioners of States and UTs 11. State Disaster Management Authorit ies 32 -34 12. Administrative Training Institutes (ATIs) of States and UTs 35 -38 13. Faculty, Disaster Management Centres in ATIs of States and UTs 39 -43 14. Chief Secretaries of States and UTs 44 -47 15. Principal Secretaries / Secretaries / Commissioners (Home) of States 48-52 and UTs 16. Director General of Police of States and UTs 53-56 17. Resident Commissioners of States and UTs in Delhi 57-60 18. National Level Institute s / Organizations dealing with Disaster 61 -76 Management 19. Organizations Providing Courses for Disaster Management 77 -78 20. SAARC Disaster Management Centre (SDMC) 79 21. National (NIRD) / State Institutes of Rural Development (SIRD) in 80 -83 India 22. Resource persons / Experts in the fields of Disaster Management 84 -133 • Animal Disaster Management and livestock Emergency Standards 84 & Guidelines (LEGS) • Basic Disaster Management 84-90 • CBRN Disasters 90-91 92-93 • Chemical -

Reconstructing the Lost Architectural Heritage of the Eighteenth to Mid-Nineteenth Century Delhi

Text and Context: Reconstructing the Lost Architectural Heritage of the eighteenth to mid-nineteenth Century Delhi Dr. Savita Kumari Assistant Professor Department of History of Art National Museum Institute Janpath, New Delhi-110011 The boundaries of the Mughal Empire that encompassed the entire Indian subcontinent during the reign of Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707), the last great Mughal ruler, shrank to Delhi and its neighbourhood during the later Mughal period (1707-1857). Delhi remained the imperial capital till 1857 but none of the Mughal rulers of the post Aurangzeb period were powerful enough to revive its past glory. Most of the time, they were puppets in the hands of powerful nobles who played a vital role in disintegrating the empire. Apart from court politics, the empire was also to face internal and external rebellions and invasions, the most significant amongst them being Afghan invasions of Nadir Shah and Ahmad Shah Abdali from the North. However, it was the East India Company that ultimately sealed the fate of the Mughal dynasty in 1857 between the Indians and the British. The city became a battleground that caused tragic destruction of life and property. During the Mutiny, opposing parties targeted the buildings of their rivals. This led to wide scale destruction and consequent changes in the architectural heritage of Delhi. In the post-Independence era, the urban development took place at the cost of many heritage sites of this period. Some buildings were demolished or altered to cater the present needs. It is unfortunate that the architectural heritage of this dynamic period is generally overshadowed by the architecture of the Great Mughals as the buildings of this period lack the grandeur and opulence of the architecture during the reign of Akbar and Shahjahan. -

Lucknow Dealers Of

Dealers of Lucknow Sl.No TIN NO. UPTTNO FIRM - NAME FIRM-ADDRESS 1 09150000006 LK0022901 EVEREADY INDUSTRIES INDIA LTD 6/A,SAPRU MARG LUCKNOW 2 09150000011 LK0019308 SHAKTI SPORTS COMPANY NEW MARKET HAZRAT GANJ LKO. 3 09150000025 LK0034158 FOOD CORPORATION OF INIDIA TC-3V VIBHUTI KHAND,GOMATI NAGAR,LUCKNOW 4 09150000030 LK0090548 BUTTON HOUSE-B B,HALWASIYA MARKET LKO. 5 09150000039 LK0099188 SHYAM LAL PARCHUNIYA NARHI HAZRAT GANJ LKO. 6 09150000044 LK0108090 RAM LAL & BROTHERS HAZRAT GANJ LUCKNOW. 7 09150000058 LK0084428 RAJ PAL JAIN(F.P.S.) NARHI BAZAR HAZRATGANJ LUCKNOW. 8 09150000063 LK0150065 LUCHYA PHARMA N.K.ROAD LUCKNOW. 9 09150000077 LK0178817 SURI WEATHER MAKERS HAZRAT GANJ LUCKNOW. 10 09150000082 LK0185031 RADLA MACHINERY EXPERTS ASHOK MARG LUCKNOW. 11 09150000096 LK0197396 UNITED ATOMOTIVES R.P.MARG LUCKNOW. 12 09150000105 LK0203133 PANNA LAL KAPOOR&CO. HALWASIA MARKET LUCKNOW. 13 09150000110 LK0209886 GUJRAT NARMADA VELLY FURTILISERS C-2 TILAK MARG LUCKNOW CO.LTD 14 09150000119 LK0208650 MAHINDRA AND MAHINDRA LTD. 7 B LANE LUCKNOW 15 09150000124 LK0214591 BRADMA OF INDIA PVT LTD. 40/4 WAZEER HASAN ROAD LUCKNOW 16 09150000138 LK0220861 TRIVENI MOTORS CO. N.K.ROAD, LUCKNOW 17 09150000143 LK0226255 RAVI AUTO SUPPLIERS ASHOK MARG LKO. 18 09150000157 LK0238867 MAN CHOW RESTORENT M.G.ROAD LKO. 19 09150000162 LK0236005 SAHNI SONS JANPATH MARKET LUCKNOW. 20 09150000176 LK0237986 ROHIT KRISHI UDYOG 1-NAVAL KISHORE ROAD LUCKNOW 21 09150000181 LK0242907 DELIGHT STORE HALWASIA MARKET LUCKNOW 22 09150000195 LK0236394 SALIG RAM KHATRY AND COMPANY HAZRAT GANJ LKO. 23 09150000204 LK0232676 RAJ KUMAR AGARWAL RANA PRATAP MARG LUCKNOW. 24 09150000218 LK0330787 SADANA ELE. JANPATH MARKET HAZRAT GANJ LKO. -

December 2012

Issue: I No: XII Compulsions Of Good Neighbourliness Pakistan's Mindset Remain Unchanged Good Governance - Strong Nation Transformation In Afghanistan and many more__ Published By : Vivekananda International Foundation 3, San Martin Marg, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi - 110021, [email protected], www.vifindia.org Contents ARTICLES - JPCs Must Have The Power To India And The South Asian Summon Ministers 51 Neighbourhood 3 - A Surya Prakash - Kanwal Sibal Special Laws To Counter Terrorism Dealing With The Neighbour From Hell - In India: A Reality Check 56 The Prime Minister Must Not Visit 19 - Dr N Manoharan 103 Pakistan - PP Shukla 107 India’s Nuclear Deterrence Must Be Professionally Managed 26 EVENTS - Brig (retd) Gurmeet Kanwal Vimarsha on “Transition in America Reviewing India-Afghanistan and China: Implications for India” Partnership 30 59 - Nitin Gokhale Grandma’s Remedies For Governance Issues 35 - Dr M N Buch CAG And The Indian Constitution 44 - Prof Makkhan Lal VIVEK : Issues and Options December – 2012 Issue: I No: XII 2 India And The South Asian Neighbourhood - Kanwal Sibal ndia’s relations with its thy neighbour as thyself” elicits no neighbours need to be obedience from the chancelleries of I analysed frankly and the world. unsentimentally, without recourse to the usual platitudes when Before talking of India and its pronouncing on the subject. It is neighbours, we should have a fashionable to assume that there clearer idea of what, in India’s is some larger moral imperative eyes, constitutes its that governs the relations between neighbourhood. Should we look at neighbours, with the bigger India’s neighbourhood country obliged to show a level of strategically or geographically? If generosity and tolerance towards a the first, then a case can be made smaller neighbour that would not out that India’s neighbourhood be applicable to the attitudes and encompasses the entire region the policies towards a more from the Straits of Hormuz to the distant country. -

British Patronage in Delhi (1803 – 1857)

SSavitaavita KKumariumari National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology, New Delhi ART AND POLITICS: BRITISH PATRONAGE IN DELHI (1803–1857) he British established their foothold in India after Sir Thomas Roe, the English diplomat, obtained permission to trade for the English East TIndia Company from the Mughal emperor Jehangir (1605–1627). By end of the seventeenth century, the company had expanded its trading operations in the major coastal cities of India. The gradual weakening of the Mughal Empire in the eighteenth century gave the East India Company a further opportunity to expand its power and maintain its own private army. In 1765, the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II (1759–1806) was forced to give the Grant of the Dīwānī1) of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa to the East India Company. However, it was in 1803 that the company became a formidable power when Shah Alam II accepted the Company’s authority in exchange for protection and mainte- nance. The British Residency at Delhi was established. This event completely changed the age-old political and social dynamics in Mughal Delhi. The event symbolised the shifting balance of power in Mughal politics. The real power belonged to the Company and was exercised by its residents. A substantial amount of funding was at the disposal of the British residents of Delhi who were directed by the Company’s government to maintain a splendid court of their own to rival the court of the Mughal emperor2). Thus, a parallel court was set up alongside that of the Mughal. It was the Kashmiri Gate of the Shahajahanabad (the Mughal imperial city) and the area beyond it on the northern side up to the ridge that became 1) Right to collect revenue. -

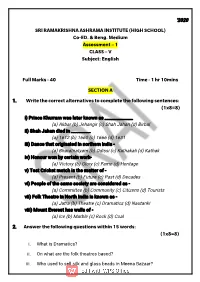

'2020 (A)Akbar(B)Jehangir(C)Shahjahan(D)Birbal (A)1612(B)1660(C

‘2020 SRI RAMAKRISHNA ASHRAMA INSTITUTE (HIGH SCHOOL) Co-ED. & Beng. Medium Assessment – 1 CLASS – V Subject: English Full Marks - 40 Time - 1 hr 10mins SECTION A 1. Write the correct alternatives to complete the following sentences: (1x8=8) i) Prince Khurram was later known as _____________ (a) Akbar (b) Jehangir (c) Shah Jahan (d) Birbal ii) Shah Jahan died in _________ (a) 1612 (b) 1660 (c) 1666 (d) 1631 iii) Dance that originated in northern india - (a) Bharatnatyam (b) Odissi (c) Kathakali (d) Kathak iv) Honour won by certain work- (a) Victory (b) Glory (c) Fame (d) Heritage v) Test Cricket match is the matter of - (a) Present (b) Future (c) Past (d) Decades vi) People of the same society are considered as - (a) Committee (b) Community (c) Citizens (d) Tourists vii) Folk Theatre in North India is known as - (a) Jatra (b) Theatre (c) Dramatics (d) Nautanki viii) Mount Everest has walls of - (a) Ice (b) Marble (c) Rock (d) Coal 2. Answer the following questions within 15 words: (1x8=8) i. What is Dramatics? ii. On what are the folk theatres based? iii. Who used to sell silk and glass beads in Meena Bazaar? iv. What do you understand by the term ‘Mausoleum’ v. What are the essential parts of a cricket match? vi. What was Phulmani’s wish? vii. Who were the first to climb Mount Everest? viii. How many workers were involved in building the Taj Mahal? 3. Answer the following questions within 25 words: (2x4=8) i. Write few lines about “Chhau dance” ii. What did Shah Jahan promise to his wife? iii. -

Tabriz Historic Bazaar (Iran) No 1346

Rotterdam, 25–28 June 2007. Tabriz Historic Bazaar (Iran) Weiss, W. M., and Westermann, K. M., The Bazaar: Markets and Merchants of the Islamic World, Thames and Hudson No 1346 Publications, London, 1998. Technical Evaluation Mission: 13–16 August 2009 Additional information requested and received from the Official name as proposed by the State Party: State Party: ICOMOS sent a letter to the State Party on 19 October 2009 on the following issues: Tabriz Historic Bazaar Complex • Further justification of the serial approach to the Location: nomination. • Further explanation of how the three chosen sites Province of East Azerbaijan relate to the overall outstanding value of the property and of how they are functionally linked, Brief description: with reference to the Goi Machid and the Sorkhāb Bazārchā areas, in relation to the wider Tabriz Historic Bazaar Complex consists of a series of Bazaar area. interconnected, covered brick structures, buildings, and • enclosed spaces for different functions. Tabriz and its Expansion of the description of the legal th protection measures. Bazaar were already prosperous and famous in the 13 • century, when the town became the capital city of the Expansion of the description of the objectives country. The importance of Tabriz as a commercial hub and the measures of the planning instruments in continued until the end of the 18th century, with the force in relation to the factors threatening the expansion of Ottoman power. Closely interwoven with property. the architectural fabric is the social and professional • Further explanation of the overall framework of organization of the Bazaar, which allows its functioning the management system and of the state of and makes it into a single, integrated entity. -

Political Role of Women During Medieval Period

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 1, January 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A An Analytical Study: Political Role of Women during Medieval Period Ms. ShabnamBharti* Abstract In fifteen and sixteen centuries Indian ladies were generally expelled from the open or political movement because of the male-centric structure of Indian culture. As a rule, ladies now were viewed as substandard compared to men and their obligations were basically limited to the home and family life. Various ladies, be that as it may, could rise above the bounds of societal desires to end up noticeably conspicuous ladies in medieval society. It was clear through non-government fields that ladies dealt with the state issues like male sovereigns. Razia Sultana turned into the main lady ruler to have ruled Delhi. Chand Bibi guarded Ahmednagar against the intense Mughal powers of Akbar in the 1590s. Jehangir's significant other NurJahan successfully employed supreme power and was perceived as the genuine power behind the Mughal royal position. The Mughal princesses Jahanara and Zebunnissa were notable writers and furthermore impacted the decision powers. Shivaji's mother, Jijabai, was ruler official due to her capacity as a warrior and a director. Mughal ladies indicated incredible pride in the activity of energy. -

Narayani.Pdf

OUR CITY, DELHI Narayani Gupta Illustrated by Mira Deshprabhu Introduction This book is intended to do two things. It seeks to make the child living in Delhi aware of the pleasures of living in a modern city, while at the same time understanding that it is a historic one. It also hopes to make him realize that a citizen has many responsibilities in helping to keep a city beautiful, and these are particularly important in a large crowded city. Most of the chapters include suggestions for activities and it is important that the child should do these as well as read the text. The book is divided into sixteen chapters, so that two chapters can be covered each month, and the course finished easily in a year. It is essential that the whole book should be read, because the chapters are interconnected. They aim to make the child familiar with map-reading, to learn some history without making it mechanical, make him aware of the need to keep the environment clean, and help him to know and love birds, flowers and trees. Our City, Delhi Narayani Gupta Contents Introduction Where Do You Live? The Ten Cities of Delhi All Roads Lead to Delhi Delhi’s River—the Yamuna The Oldest Hills—the Ridge Delhi’s Green Spaces We Also Live in Delhi Our Houses Our Shops Who Governs Delhi? Festivals A Holiday Excursion Delhi in 1385 Delhi in 1835 Delhi in 1955 Before We Say Goodbye 1. Where Do You Live? This is a book about eight children and the town they live in.