Gender Issues 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Far-Right Ciswomen Activists and Political Representation

The far-right ciswomen activists and political representation Magdalena KOMISARZ, 01517750 Innsbruck, November 2018 Masterarbeit eingereicht an der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Fakultät für Soziale und Politische Wissenschaften zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Master of Arts Interfakultäres Masterstudium Gender, Kultur und Sozialer Wandel betreut von: Prof.in Dr.in Nikita Dhawan Institut für Politikwissenschaft Fakultät für Soziale und Politische Wissenschaften I. Index 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 2 Far-right wing ciswomen activists ......................................................................................... 4 2.1 Production of ideology by ciswomen in the far-right ................................................... 4 2.2 Comparison between cismen and ciswomen ............................................................... 7 2.3 Motives........................................................................................................................ 12 2.4 Intersectional interventions ........................................................................................ 14 2.5 Feminationalism? ........................................................................................................ 16 2.6 Far-right wing activists – Polish context ..................................................................... 18 2.6.1 Anti-gender movement and the Catholic Church in Poland ..................... 19 -

Chapter 5 the Continuity of Representation: MP Renomination Rates and Electoral Volatility

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/18567 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Gherghina, Sergiu Title: Explaining electoral volatility in Central and Eastern Europe : a party organizational approach Issue Date: 2012-03-08 Chapter 5 The Continuity of Representation: MP Renomination Rates and Electoral Volatility Introduction The low levels of confidence vested by citizens in the legislature and the effective loss of its competencies in favor of executive agencies (Mishler and Rose 1994; Newton and Norris 2000; Loewenberg et al. 2002; 2010; Mezey, 2008, 181) does not alter the importance of parliamentary representation for democracy. Following the breakdown of communism, most CEE countries placed Parliaments at the core of their institutional setting (Lijphart 1992; Elster et al. 1998). In this sense, previous studies reveal the dominance held by the legislature in relationship with the other state actors (Gherghina 2007; Elgie and Moestrup 2008). Two features of the post-communist legislatures are observable. First, they start as transitional legislatures: with the exception of Poland, they were in place before the drafting of constitutions. They lacked regulations on internal procedures and their effects on behavior and policy occurred at a later stage. Second, as a consequence of the central role played by Parliaments in the institutional design, the CEE legislatures became the major stage where politicians met and where political parties made their presence visible (Olson 1998b). In the words of Polsby (1975) – who differentiates between Parliaments as transformative institutions and as arenas – the newly emerged CEE legislatures appear to be part of the latter category. -

The Polish Profeminist Movement

www.ssoar.info The Polish profeminist movement Wojnicka, Katarzyna Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: Verlag Barbara Budrich Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Wojnicka, K. (2012). The Polish profeminist movement. GENDER - Zeitschrift für Geschlecht, Kultur und Gesellschaft, 4(3), 25-40. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-396370 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-SA Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-SA Licence Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen) zur Verfügung gestellt. (Attribution-ShareAlike). For more Information see: Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de Katarzyna Wojnicka The Polish profeminist movement Zusammenfassung Summary Die profeministische Bewegung in Polen In my article I explore an issue which is part of the phenomena termed “men’s social mo- Der Artikel beschäftigt sich mit einem The- vements”. Men’s social movements are new ma, das von der zeitgenössischen Soziologie social movements in which actors focus on unter „Soziale Bewegungen von Männern“ gender issues as the main criteria for building gefasst wird. Es handelt sich um neue Bewe- collective identity. They include the men’s and gungen, die sich vor allem dadurch auszeich- fathers’ rights movement, the mythopoetic nen, dass die Akteure das Themenfeld der movement, male religious movements and Geschlechtergerechtigkeit als ein wesentli- the profeminist movement. In my article I pre- ches Kriterium zur Bildung einer gemein- sent the case of the Polish profeminist move- schaftlichen Identität betrachten. -

Framing Solidarity. Feminist Patriots Opposing the Far Right in Contemporary Poland

Open Cultural Studies 2019; 3: 469-484 Research Article Jennifer Ramme* Framing Solidarity. Feminist Patriots Opposing the Far Right in Contemporary Poland https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2019-0040 Received October 30, 2018; accepted May 30, 2019 Abstract: Due to the attempts to restrict the abortion law in Poland in 2016, we could observe a new broad- based feminist movement emerge. This successful movement became known worldwide through the Black Protests and the massive Polish Women’s Strike that took place in October 2016. While this new movement is impressive in its scope and can be described as one of the most successful opposition movements to the ethno-nationalist right wing and fundamentalist Catholicism, it also deploys a patriotic rhetoric and makes use of national symbols and categories of belonging. Feminism and nationalism in Poland are usually described as in opposition, although that relationship is much more complex and changing. Over decades, a general shift towards right-wing nationalism in Poland has occurred, which, in various ways, has also affected feminist actors and (counter)discourses. It seems that patriotism is used to combat nationalism, which has proved to be a successful strategy. Taking the example of feminist mobilizations and movements in Poland, this paper discusses the (im)possible link between patriotism, nationalism and feminism in order to ask what it means for feminist politics and female solidarity when belonging is framed in different ways. Keywords: framing belonging; social movements; ethno-nationalism; embodied nationalism; public discourse A surprising response to extreme nationalism and religious fundamentalism in Poland appeared in the mass mobilization against a legislative initiative introducing a total ban on abortion in 2016, which culminated in a massive Women’s Strike in October the same year. -

Personal Feminist Journeys

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The European Feminist Forum: a Herstory (2004-2008) Dütting, G.; Harcourt, W.; Lohmann, K.; McDevitt-Pugh, L.; Semeniuk, J.; Wieringa, S. Publication date 2009 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Dütting, G., Harcourt, W., Lohmann, K., McDevitt-Pugh, L., Semeniuk, J., & Wieringa, S. (2009). The European Feminist Forum: a Herstory (2004-2008). Aletta Institute for Women’s History. http://europeanfeministforum.org/IMG/pdf/EFF_Herstory_web.pdf General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 The European Feminist Forum The European Feminist Forum The European Feminist Forum A Herstory (2004–2008) A Herstory (2004–2008) Gisela Dütting, Wendy Harcourt, Kinga Lohmann, Lin McDevitt-Pugh, Joanna Semeniuk and Saskia Wieringa The European Feminist Forum A Herstory (2004–2008) Gisela Dütting, Wendy Harcourt, Kinga Lohmann, Lin McDevitt-Pugh, Joanna Semeniuk and Saskia Wieringa © 2009 Aletta – Institute for Women’s History All rights reserved, including those of translation into foreign languages. -

Backlash in Gender Equality and Women's and Girls' Rights

STUDY Requested by the FEMM committee Backlash in Gender Equality and Women’s and Girls’ Rights WOMEN’S RIGHTS & GENDER EQUALITY Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs Directorate General for Internal Policies of the Union PE 604.955– June 2018 EN Backlash in Gender Equality and Women’s and Girls’ Rights STUDY Abstract This study, commissioned by the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the FEMM Committee, is designed to identify in which fields and by which means the backlash in gender equality and women’s and girls’ rights in six countries (Austria, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia) is occurring. The backlash, which has been happening over the last several years, has decreased the level of protection of women and girls and reduced access to their rights. ABOUT THE PUBLICATION This research paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality and commissioned, overseen and published by the Policy Department for Citizen's Rights and Constitutional Affairs. Policy Departments provide independent expertise, both in-house and externally, to support European Parliament committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic scrutiny over EU external and internal policies. To contact the Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs or to subscribe to its newsletter please write to: [email protected] RESPONSIBLE RESEARCH ADMINISTRATOR Martina SCHONARD Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs European Parliament B-1047 Brussels E-mail: [email protected] AUTHORS Borbála JUHÁSZ, indipendent expert to EIGE dr. -

Survival Kit in Riga Maria Janion a Great European Intellectual

A quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. December 2011. Vol IV:4 From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) commentaries: Södertörn University, Stockholm Poland and Russia Survival Kit in Riga BALTIC Women’s Solidarity W O Rbalticworlds.com L D S Maria Janion A great European The dividing intellectual Christmas tree also in this issue ILLUSTRATION: RAGNI SVENSSON RUSSIAN INFRASTRUCTURE / YUGOSLAVIAN WAR MONUMENTS / WITTE / NEW SPATIAL HISTORY / MOSCOW FASHION global2 week editors’ column BALTIC editorial 3 Culture in More diatribe than dialogue when old top dogs deliberate the periphery W O R L Dbalticworlds.com S “Dialogue”, said Gen- thing we have not done!” Ekaterina Kalinina finds revanchism, Age of unexpected nady Burbulis, first The Russians had already or a certain measure of megalomania, Sponsored by the Foundation deputy to the chairman lost all their savings by to be the reason that two indepen- for Baltic and East European Studies of the government under 1990. “They had nothing dent fashion weeks have been held in revolts Boris Yeltsin, at a top- left to lose”, he said. “It St. Petersburg in the last two years. a quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. December 2011. vol iv:4 from the centre for Baltic and east european studies (cBees) commentaries: level seminar with former was all fictitious money.” Despite several similar events held in södertörn university, stockholm poland and russia Survival kit i n R i g a BALTIC Wom e n’s heads of state in Soviet- And the former engine Moscow as well, the fashion industry S ol i d a r it y contents orld War I saw the nomic-structural thinking and action at WORLDS D L R O W balticworlds.com Maria Janion A great European ruled Europe convened of growth, the military- is not an up-and-coming business in The dividing intellectual dissolution of three the Union level. -

Threats to Feminist Identity and Reactions to Gender Discrimination

Sex Roles (2013) 68:605–619 DOI 10.1007/s11199-013-0272-5 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Threats to Feminist Identity and Reactions to Gender Discrimination Aleksandra Cichocka & Agnieszka Golec de Zavala & Mirek Kofta & Joanna Rozum Published online: 7 March 2013 # The Author(s) 2013. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The aim of this research was to examine condi- Introduction tions that modify feminists’ support for women as targets of gender discrimination. In an experimental study we tested a In 2010 we celebrated the “Year of the Woman” in U.S. hypothesis that threatened feminist identity will lead to politics (Parker 2010, para. 1). Many women, like Tea Party greater differentiation between feminists and conservative leaders such as Sarah Palin and Christine O’Donnell, were women as victims of discrimination and, in turn, a decrease ranked among the most successful politicians of 2010 and in support for non-feminist victims. The study was appeared to be on their way to becoming “the 21st century conducted among 96 young Polish female professionals symbol of American women in politics” (Holmes and and graduate students from Gender Studies programs in Traister 2010, para. 3). At the same time, women all over Warsaw who self-identified as feminists (Mage=22.23). the world continue to be under-represented in the majority Participants were presented with a case of workplace gender of political and business institutions. For example, only 14 discrimination. Threat to feminist identity and worldview of countries have democratically elected female leaders the discrimination victim (feminist vs. conservative) were (Catalyst 2012a) and a gender gap still exists even in most varied between research conditions. -

Where Feminists Dare: the Challenge to the Heteropatriarchal and Neo-Conservative Backlash in Italy and Poland

Title: Where feminists dare : the challenge to the heteropatriarchal and neo- conservative backlash in Italy and Poland Author: Agnieszka Bielska-Brodziak, Marlena Drapalska-Grochowicz, Caterina Peroni, Elisa Rapetti Citation style: Bielska-Brodziak Agnieszka, Drapalska-Grochowicz Marlena, Peroni Caterina, Rapetti Elisa. (2020). Where feminists dare : the challenge to the heteropatriarchal and neo-conservative backlash in Italy and Poland. "Onati Socio - Legal Series" (Vol. 10, no. 1S (2020), s. 38S-66S), DOI:10.35295/osls.iisl/0000-0000-0000-1156 Where feminists dare: The challenge to the heteropatriarchal and neo-conservative backlash in Italy and Poland OÑATI SOCIO-LEGAL SERIES VOLUME 10, ISSUE 1S (2020), 38S–66S: THE FOURTH WAVE OF FEMINISM: FROM SOCIAL NETWORKING AND SELF-DETERMINATION TO SISTERHOOD DOI LINK: HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.35295/OSLS.IISL/0000-0000-0000-1156 RECEIVED 22 JANUARY 2020, ACCEPTED 02 MARCH 2020 AGNIESZKA BIELSKA-BRODZIAK∗ MARLENA DRAPALSKA-GROCHOWICZ∗ CATERINA PERONI∗ ELISA RAPETTI∗ ∗ Agnieszka Bielska-Brodziak, an associate professor of the University of Silesia in Katowice at the Faculty of Law and Administration, a practicing lawyer. Interests: 1. theory and philosophy of law, in particular, law-making process and legal interpretation, 2. the interface of law, medicine, and bioethics. Within this area, she is particularly interested in the legal (public and private) consequences of legal, biological, and gender identity conflicts. She studies two groups of entities: transgender and intersex people. She is a member of an interdisciplinary medical and legal group working on improving standards of care for underage and transgender patients as well as changing Polish law in the field of gender recognition. -

Download Download

Where feminists dare: The challenge to the heteropatriarchal and neo-conservative backlash in Italy and Poland OÑATI SOCIO-LEGAL SERIES VOLUME 10, ISSUE 1S (2020), 38S–66S: THE FOURTH WAVE OF FEMINISM: FROM SOCIAL NETWORKING AND SELF-DETERMINATION TO SISTERHOOD DOI LINK: HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.35295/OSLS.IISL/0000-0000-0000-1156 RECEIVED 22 JANUARY 2020, ACCEPTED 02 MARCH 2020 AGNIESZKA BIELSKA-BRODZIAK∗ MARLENA DRAPALSKA-GROCHOWICZ∗ CATERINA PERONI∗ ELISA RAPETTI∗ ∗ Agnieszka Bielska-Brodziak, an associate professor of the University of Silesia in Katowice at the Faculty of Law and Administration, a practicing lawyer. Interests: 1. theory and philosophy of law, in particular, law-making process and legal interpretation, 2. the interface of law, medicine, and bioethics. Within this area, she is particularly interested in the legal (public and private) consequences of legal, biological, and gender identity conflicts. She studies two groups of entities: transgender and intersex people. She is a member of an interdisciplinary medical and legal group working on improving standards of care for underage and transgender patients as well as changing Polish law in the field of gender recognition. She is a Head of Unit UNESCO Chair in Bioethics at the University of Silesia. She participates in the project HERA Healthcare as a Public Space: Social Integration and Social Diversity in the Context of Access to Healthcare in Europe. Contact details: University of Silesia in Katowice, Faculty of Law and Administration, ul. Bankowa 11, Katowice, Poland. Email address: [email protected] ∗ PhD candidate in the Department of Theory and Philosophy of Law in the Faculty of Law and Administration of University of Silesia in Katowice. -

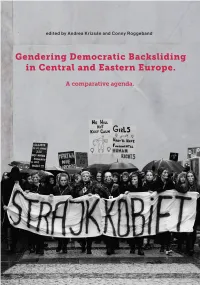

Gendering Democratic Backsliding in Central and Eastern Europe. A

CENTER FOR POLICY STUDIES CENTRAL EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY Nádor utca 9., H–1051 Budapest, Hungary [email protected], http://cps.ceu.edu Published in 2019 by the Center for Policy Studies, Central European University © CEU CPS, 2019 ISBN 978-615-5547-07-2 (pdf) The views in this publication are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Central European University or the Research Executive Agency of the European Commission. This text may be used only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. This publication has been produced in the framework of the project ‘Enhancing the EU’s Transboundary Crisis Management Capacities: Strategies for Multi-Level Leadership (TransCrisis)’. The project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 649484. Cover design: Borbala Soos Design & layout: Borbala Varga “Gendering Democratic Backsliding in Central and Eastern Europe is a must-read for anyone interested in the contemporary dynamics of illiberal democracies and reconfiguration of gender regimes. The theoretical introduction by Andrea Krizsán and Conny Roggeband displays great clarity and provides a neat structure for the whole volume. The book collects thick, but well nuanced and insightful analysis of recent developments of four CEE countries: Croatia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. The case studies are fascinating, impressive for their richness, but thanks to the common analytical framework, the volume is consistent and accessible. -

Del Autoritarismo a La Democracia. La Experiencia Polaca

tapa del auto a la demo.pdf 1 31/10/2014 04:10:28 p.m. Esta publicación trata sobre los cambios excepcionales que han ocurrido en los últimos veinticinco años en Polonia: un país que durante varias décadas se encontró sometido al bloque soviético, pero que, a pesar del legado totalitario y del autoritarismo comunista, buscaba la democracia. La lectura del libro deja entender la esencia de estos cambios, los debates y discusiones políticos, sociales y El Instituto Lech Wałęsa es una organización no culturales que los acompañaban. Hace hincapié en el complejo camino que ha tomado esta nación de Europa gubernamental, sin fines de lucro, apolítica, fundada El Centro para la Apertura y el Desarrollo de América Central, el país de San Juan Pablo II, de Lech Wałęsa y de la Revolución de Solidaridad en los años 1980-1981, por el presidente Lech Wałęsa en diciembre de 1995 Latina (CADAL) es una fundación privada, sin fines de polacaLa experiencia movimiento que proclamó los cambios prodemocráticos que se efectuaron pocos años más tarde en varios como la primera institución en Polonia. lucro y apartidaria, cuya misión consiste en promover países del esparcido bloque soviético y que se mantienen hasta la fecha. los valores democráticos, observar el desempeño político, económico e institucional y formular Todos los proyectos llevados a cabo como parte de las propuestas de políticas públicas que contribuyan al Gracias al esfuerzo conjunto del Programa Latinoamericano del Instituto de Lech Wałęsa y del Centro para la actividades estatutarias del Instituto, tales como buen gobierno y al bienestar de las personas.