The Polish Profeminist Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Far-Right Ciswomen Activists and Political Representation

The far-right ciswomen activists and political representation Magdalena KOMISARZ, 01517750 Innsbruck, November 2018 Masterarbeit eingereicht an der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Fakultät für Soziale und Politische Wissenschaften zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Master of Arts Interfakultäres Masterstudium Gender, Kultur und Sozialer Wandel betreut von: Prof.in Dr.in Nikita Dhawan Institut für Politikwissenschaft Fakultät für Soziale und Politische Wissenschaften I. Index 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 2 Far-right wing ciswomen activists ......................................................................................... 4 2.1 Production of ideology by ciswomen in the far-right ................................................... 4 2.2 Comparison between cismen and ciswomen ............................................................... 7 2.3 Motives........................................................................................................................ 12 2.4 Intersectional interventions ........................................................................................ 14 2.5 Feminationalism? ........................................................................................................ 16 2.6 Far-right wing activists – Polish context ..................................................................... 18 2.6.1 Anti-gender movement and the Catholic Church in Poland ..................... 19 -

Framing Solidarity. Feminist Patriots Opposing the Far Right in Contemporary Poland

Open Cultural Studies 2019; 3: 469-484 Research Article Jennifer Ramme* Framing Solidarity. Feminist Patriots Opposing the Far Right in Contemporary Poland https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2019-0040 Received October 30, 2018; accepted May 30, 2019 Abstract: Due to the attempts to restrict the abortion law in Poland in 2016, we could observe a new broad- based feminist movement emerge. This successful movement became known worldwide through the Black Protests and the massive Polish Women’s Strike that took place in October 2016. While this new movement is impressive in its scope and can be described as one of the most successful opposition movements to the ethno-nationalist right wing and fundamentalist Catholicism, it also deploys a patriotic rhetoric and makes use of national symbols and categories of belonging. Feminism and nationalism in Poland are usually described as in opposition, although that relationship is much more complex and changing. Over decades, a general shift towards right-wing nationalism in Poland has occurred, which, in various ways, has also affected feminist actors and (counter)discourses. It seems that patriotism is used to combat nationalism, which has proved to be a successful strategy. Taking the example of feminist mobilizations and movements in Poland, this paper discusses the (im)possible link between patriotism, nationalism and feminism in order to ask what it means for feminist politics and female solidarity when belonging is framed in different ways. Keywords: framing belonging; social movements; ethno-nationalism; embodied nationalism; public discourse A surprising response to extreme nationalism and religious fundamentalism in Poland appeared in the mass mobilization against a legislative initiative introducing a total ban on abortion in 2016, which culminated in a massive Women’s Strike in October the same year. -

Personal Feminist Journeys

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The European Feminist Forum: a Herstory (2004-2008) Dütting, G.; Harcourt, W.; Lohmann, K.; McDevitt-Pugh, L.; Semeniuk, J.; Wieringa, S. Publication date 2009 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Dütting, G., Harcourt, W., Lohmann, K., McDevitt-Pugh, L., Semeniuk, J., & Wieringa, S. (2009). The European Feminist Forum: a Herstory (2004-2008). Aletta Institute for Women’s History. http://europeanfeministforum.org/IMG/pdf/EFF_Herstory_web.pdf General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 The European Feminist Forum The European Feminist Forum The European Feminist Forum A Herstory (2004–2008) A Herstory (2004–2008) Gisela Dütting, Wendy Harcourt, Kinga Lohmann, Lin McDevitt-Pugh, Joanna Semeniuk and Saskia Wieringa The European Feminist Forum A Herstory (2004–2008) Gisela Dütting, Wendy Harcourt, Kinga Lohmann, Lin McDevitt-Pugh, Joanna Semeniuk and Saskia Wieringa © 2009 Aletta – Institute for Women’s History All rights reserved, including those of translation into foreign languages. -

Backlash in Gender Equality and Women's and Girls' Rights

STUDY Requested by the FEMM committee Backlash in Gender Equality and Women’s and Girls’ Rights WOMEN’S RIGHTS & GENDER EQUALITY Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs Directorate General for Internal Policies of the Union PE 604.955– June 2018 EN Backlash in Gender Equality and Women’s and Girls’ Rights STUDY Abstract This study, commissioned by the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the FEMM Committee, is designed to identify in which fields and by which means the backlash in gender equality and women’s and girls’ rights in six countries (Austria, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia) is occurring. The backlash, which has been happening over the last several years, has decreased the level of protection of women and girls and reduced access to their rights. ABOUT THE PUBLICATION This research paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality and commissioned, overseen and published by the Policy Department for Citizen's Rights and Constitutional Affairs. Policy Departments provide independent expertise, both in-house and externally, to support European Parliament committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic scrutiny over EU external and internal policies. To contact the Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs or to subscribe to its newsletter please write to: [email protected] RESPONSIBLE RESEARCH ADMINISTRATOR Martina SCHONARD Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs European Parliament B-1047 Brussels E-mail: [email protected] AUTHORS Borbála JUHÁSZ, indipendent expert to EIGE dr. -

Gender Issues 2009

The Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia and Ukraine Gender Issues 2009 Gender Issues 2009: Gender Equality Discourse in Times of Transformation, 1989-2009 Heinrich Böll Foundation Regional Office Warsaw ul. Żurawia 45, 00-680 Warsaw, Poland phone: + 48 22 59 42 333, e-mail: [email protected] Heinrich Böll Foundation The Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia and Ukraine Gender Issues 2009: Gender Equality Discourse in Times of Transformation, 1989-2009 The publication was elaborated within the Framework of the Regional Programme „Gender Democracy and Women’s Politics” Translation: Kateřina Kastnerová, Natalia Kertyczak, Katarzyna Nowakowska, Eva Riečanská Editing: Justyna Włodarczyk Project coordinator: Agnieszka Grzybek Graphic design: Studio 27 Published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation Regional Office Warsaw. Printed in Warsaw, November 2009. This project has been supported by the European Union: Financing of organizations that are active on the European level for an active European society. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Heinrich Böll Foundation. ISBN: 978-83-61340-48-5 Copyright by the Heinrich Böll Foundation Regional Office Warsaw. All rights reserved. This publication can be ordered at: Heinrich Böll Foundation Regional Office Warsaw, ul. Żurawia 45, 00-680 Warsaw, Poland phone: + 48 22 59 42 333 e-mail: [email protected] www.boell.pl CONTENTS Agnieszka Rochon, Agnieszka Grzybek Introduction . 5 Nina Bosničová, Kristýna Ciprová, Alexandra Jachanová-Doleželová, Kateřina Machovcová, Linda Sokačová Gender Changes in the Czech Republic after 1989. .9 Anna Czerwińska Poland: 20 years – 20 changes. .47 Jana Cviková, Jana Juráňová Feminisms for Beginners. -

Survival Kit in Riga Maria Janion a Great European Intellectual

A quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. December 2011. Vol IV:4 From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) commentaries: Södertörn University, Stockholm Poland and Russia Survival Kit in Riga BALTIC Women’s Solidarity W O Rbalticworlds.com L D S Maria Janion A great European The dividing intellectual Christmas tree also in this issue ILLUSTRATION: RAGNI SVENSSON RUSSIAN INFRASTRUCTURE / YUGOSLAVIAN WAR MONUMENTS / WITTE / NEW SPATIAL HISTORY / MOSCOW FASHION global2 week editors’ column BALTIC editorial 3 Culture in More diatribe than dialogue when old top dogs deliberate the periphery W O R L Dbalticworlds.com S “Dialogue”, said Gen- thing we have not done!” Ekaterina Kalinina finds revanchism, Age of unexpected nady Burbulis, first The Russians had already or a certain measure of megalomania, Sponsored by the Foundation deputy to the chairman lost all their savings by to be the reason that two indepen- for Baltic and East European Studies of the government under 1990. “They had nothing dent fashion weeks have been held in revolts Boris Yeltsin, at a top- left to lose”, he said. “It St. Petersburg in the last two years. a quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. December 2011. vol iv:4 from the centre for Baltic and east european studies (cBees) commentaries: level seminar with former was all fictitious money.” Despite several similar events held in södertörn university, stockholm poland and russia Survival kit i n R i g a BALTIC Wom e n’s heads of state in Soviet- And the former engine Moscow as well, the fashion industry S ol i d a r it y contents orld War I saw the nomic-structural thinking and action at WORLDS D L R O W balticworlds.com Maria Janion A great European ruled Europe convened of growth, the military- is not an up-and-coming business in The dividing intellectual dissolution of three the Union level. -

Threats to Feminist Identity and Reactions to Gender Discrimination

Sex Roles (2013) 68:605–619 DOI 10.1007/s11199-013-0272-5 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Threats to Feminist Identity and Reactions to Gender Discrimination Aleksandra Cichocka & Agnieszka Golec de Zavala & Mirek Kofta & Joanna Rozum Published online: 7 March 2013 # The Author(s) 2013. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The aim of this research was to examine condi- Introduction tions that modify feminists’ support for women as targets of gender discrimination. In an experimental study we tested a In 2010 we celebrated the “Year of the Woman” in U.S. hypothesis that threatened feminist identity will lead to politics (Parker 2010, para. 1). Many women, like Tea Party greater differentiation between feminists and conservative leaders such as Sarah Palin and Christine O’Donnell, were women as victims of discrimination and, in turn, a decrease ranked among the most successful politicians of 2010 and in support for non-feminist victims. The study was appeared to be on their way to becoming “the 21st century conducted among 96 young Polish female professionals symbol of American women in politics” (Holmes and and graduate students from Gender Studies programs in Traister 2010, para. 3). At the same time, women all over Warsaw who self-identified as feminists (Mage=22.23). the world continue to be under-represented in the majority Participants were presented with a case of workplace gender of political and business institutions. For example, only 14 discrimination. Threat to feminist identity and worldview of countries have democratically elected female leaders the discrimination victim (feminist vs. conservative) were (Catalyst 2012a) and a gender gap still exists even in most varied between research conditions. -

Where Feminists Dare: the Challenge to the Heteropatriarchal and Neo-Conservative Backlash in Italy and Poland

Title: Where feminists dare : the challenge to the heteropatriarchal and neo- conservative backlash in Italy and Poland Author: Agnieszka Bielska-Brodziak, Marlena Drapalska-Grochowicz, Caterina Peroni, Elisa Rapetti Citation style: Bielska-Brodziak Agnieszka, Drapalska-Grochowicz Marlena, Peroni Caterina, Rapetti Elisa. (2020). Where feminists dare : the challenge to the heteropatriarchal and neo-conservative backlash in Italy and Poland. "Onati Socio - Legal Series" (Vol. 10, no. 1S (2020), s. 38S-66S), DOI:10.35295/osls.iisl/0000-0000-0000-1156 Where feminists dare: The challenge to the heteropatriarchal and neo-conservative backlash in Italy and Poland OÑATI SOCIO-LEGAL SERIES VOLUME 10, ISSUE 1S (2020), 38S–66S: THE FOURTH WAVE OF FEMINISM: FROM SOCIAL NETWORKING AND SELF-DETERMINATION TO SISTERHOOD DOI LINK: HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.35295/OSLS.IISL/0000-0000-0000-1156 RECEIVED 22 JANUARY 2020, ACCEPTED 02 MARCH 2020 AGNIESZKA BIELSKA-BRODZIAK∗ MARLENA DRAPALSKA-GROCHOWICZ∗ CATERINA PERONI∗ ELISA RAPETTI∗ ∗ Agnieszka Bielska-Brodziak, an associate professor of the University of Silesia in Katowice at the Faculty of Law and Administration, a practicing lawyer. Interests: 1. theory and philosophy of law, in particular, law-making process and legal interpretation, 2. the interface of law, medicine, and bioethics. Within this area, she is particularly interested in the legal (public and private) consequences of legal, biological, and gender identity conflicts. She studies two groups of entities: transgender and intersex people. She is a member of an interdisciplinary medical and legal group working on improving standards of care for underage and transgender patients as well as changing Polish law in the field of gender recognition. -

Download Download

Where feminists dare: The challenge to the heteropatriarchal and neo-conservative backlash in Italy and Poland OÑATI SOCIO-LEGAL SERIES VOLUME 10, ISSUE 1S (2020), 38S–66S: THE FOURTH WAVE OF FEMINISM: FROM SOCIAL NETWORKING AND SELF-DETERMINATION TO SISTERHOOD DOI LINK: HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.35295/OSLS.IISL/0000-0000-0000-1156 RECEIVED 22 JANUARY 2020, ACCEPTED 02 MARCH 2020 AGNIESZKA BIELSKA-BRODZIAK∗ MARLENA DRAPALSKA-GROCHOWICZ∗ CATERINA PERONI∗ ELISA RAPETTI∗ ∗ Agnieszka Bielska-Brodziak, an associate professor of the University of Silesia in Katowice at the Faculty of Law and Administration, a practicing lawyer. Interests: 1. theory and philosophy of law, in particular, law-making process and legal interpretation, 2. the interface of law, medicine, and bioethics. Within this area, she is particularly interested in the legal (public and private) consequences of legal, biological, and gender identity conflicts. She studies two groups of entities: transgender and intersex people. She is a member of an interdisciplinary medical and legal group working on improving standards of care for underage and transgender patients as well as changing Polish law in the field of gender recognition. She is a Head of Unit UNESCO Chair in Bioethics at the University of Silesia. She participates in the project HERA Healthcare as a Public Space: Social Integration and Social Diversity in the Context of Access to Healthcare in Europe. Contact details: University of Silesia in Katowice, Faculty of Law and Administration, ul. Bankowa 11, Katowice, Poland. Email address: [email protected] ∗ PhD candidate in the Department of Theory and Philosophy of Law in the Faculty of Law and Administration of University of Silesia in Katowice. -

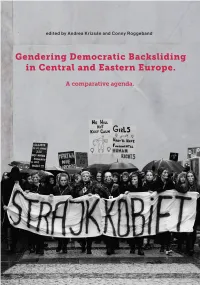

Gendering Democratic Backsliding in Central and Eastern Europe. A

CENTER FOR POLICY STUDIES CENTRAL EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY Nádor utca 9., H–1051 Budapest, Hungary [email protected], http://cps.ceu.edu Published in 2019 by the Center for Policy Studies, Central European University © CEU CPS, 2019 ISBN 978-615-5547-07-2 (pdf) The views in this publication are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Central European University or the Research Executive Agency of the European Commission. This text may be used only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. This publication has been produced in the framework of the project ‘Enhancing the EU’s Transboundary Crisis Management Capacities: Strategies for Multi-Level Leadership (TransCrisis)’. The project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 649484. Cover design: Borbala Soos Design & layout: Borbala Varga “Gendering Democratic Backsliding in Central and Eastern Europe is a must-read for anyone interested in the contemporary dynamics of illiberal democracies and reconfiguration of gender regimes. The theoretical introduction by Andrea Krizsán and Conny Roggeband displays great clarity and provides a neat structure for the whole volume. The book collects thick, but well nuanced and insightful analysis of recent developments of four CEE countries: Croatia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. The case studies are fascinating, impressive for their richness, but thanks to the common analytical framework, the volume is consistent and accessible. -

83Rd Annual Convention Southern States Communication Association

83rd Annual Convention Southern States Communication Association 23rd Annual Theodore Clevenger Undergraduate Honors Conference April 10-14, 2013 The Seelbach Hilton Louisville, Kentucky COMMUNICATION, CHOICES, AND CONSEQUENCES PRESIDENT: Monette Callaway, Hinds County Community College VICE PRESIDENT: John C. Meyer, University of Southern Mississippi VICE PRESIDENT ELECT: John Haas, University of Tennessee EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Carl Cates, Valdosta State University TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome UHC Welcome and Acknowledgements Hotel Map Registration Exhibit Schedule Division and Interest Group Programs Index Business Meetings Wednesday Sessions Thursday Sessions Friday Sessions Saturday Sessions Sunday Sessions Association Officers Representatives to NCA Committees Divisions Interest Groups Charter Members Executive Directors SCJ Editors SSCA Presidents Award Recipients Past Conventions and Hotels Life Members Patron Members Emeritus Members Institutional Members Constitution Advertiser Index Index of Participants 2014 Call for Papers Welcome to the 83rd Annual SSCA Convention Dear SSCA Colleagues: Welcome to Louisville, a city that provides a truly pleasant riverside surprise. Interesting attractions can be found including right around us downtown and nearby historic college and residential areas (like Old Louisville not far away). Horse aficionados can check out Churchill Downs, site of the Kentucky Derby and museum as well as horse farms out in the country. Baseball fans will enjoy the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory, a short walk from the hotel. Museums downtown include the Muhammad Ali Center. The Ethnography Interest Group plans an interactive panel late Saturday afternoon for those having visited any of those three major attractions. The Frazier History Museum and the Louisville Science Center are also close by, with an Imax theater adding to its many hands-on displays. -

Journal of Feminist Scholarship Issue 1 (Fall 2011) Table of Contents Ii from the Editors

Journal of Feminist Scholarship Issue 1 (Fall 2011) TABLE OF CONTENTS ii From the Editors 2 Feminism and Feminist Scholarship Today 3 Amrita Basu 4 Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards 5 Debra A. Castillo 7 Rachel Blau DuPlessis 9 Agnieszka Graff 10 Elizabeth Grosz 11 Joy A. James 13 Michael Kimmel 14 Toril Moi Karen M. Offen 16 Articles Feminist Debate in Tawain’s Buddhism: The Issue of the Eight Garudhammas Chiung Hwang Chen, Brigham Young University-Hawaii 33 Healthism and the Bodies of Women: Pleasure and Discipline in the War against Obesity Talia L. Welsh, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga 49 Grappling with Gender: Exploring Masculinity and Gender in the Bodies, Performances, and Emotions of Scholastic Wrestlers Phyllis L. Baker, University of Northern Iowa Douglas R. Hotek, University of Northern Iowa 65 New Age Fairy Tales: The Abject Female Hero in El laberinto del fauno and La rebelión de los conejos mágicos Patricia Lapolla Swier, Wake Forest University 80 Viewpoint The Rise and Fall of Western Homohysteria Eric Anderson, University of Winchester Journal of Feminist Scholarship 1 (Fall 2011) i FROM THE EDITORS We are proud and excited to introduce the inaugural issue of the Journal of Feminist Scholarship (JFS). The fundamental aims of JFS are to offer an open-access academic forum for the publication of innovative, peer-reviewed feminist scholarship across the disciplines and to encourage productive debates among scholars and activists interested in examining methodological directions and political contexts and ramifications of feminist inquiry. As a field of human endeavor whose political goals are inseparable from the intellectual perspectives it embraces, feminism has both matured and diversified tremendously over the past several decades of its dynamic development throughout the world.