5.3. the Quena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Specific Features of a Closed-End Pipe Blown by a Turbulent Jet: Aeroacoustics of the Panpipes

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATOLICA DE CHILE SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING SPECIFIC FEATURES OF A CLOSED-END PIPE BLOWN BY A TURBULENT JET: AEROACOUSTICS OF THE PANPIPES FELIPE IGNACIO MENESES DÍAZ Thesis submitted to the Office of Research and Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Engineering Advisors: MIGUEL RÍOS O. PATRICIO DE LA CUADRA B. Santiago de Chile, September of 2015 c MMXV, FELIPE IGNACIO MENESES DÍAZ PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATOLICA DE CHILE SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING SPECIFIC FEATURES OF A CLOSED-END PIPE BLOWN BY A TURBULENT JET: AEROACOUSTICS OF THE PANPIPES FELIPE IGNACIO MENESES DÍAZ Members of the Committee: MIGUEL RÍOS O. PATRICIO DE LA CUADRA B. DOMINGO MERY Q. SEBASTIÁN FINGERHUTH M. ÁLVARO SOTO A. Thesis submitted to the Office of Research and Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Engineering Santiago de Chile, September of 2015 c MMXV, FELIPE IGNACIO MENESES DÍAZ Gracias a mi familia, mis amigos, mis colegas y mis mentores. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to give special thanks to my advisor Patricio de la Cuadra for his guidance and support, and for continuously sharing his experience and knowledge. I also wish to thank Benoit Fabre and Roman Auvray from the Laboratoire d’acoustique musicale (LAM) of the Jean le Rond d’Alembert Institute (UPMC) of the University of Paris VI, for their hospitality and their wise and helpful advice, and for a great teamwork experience. From the Centro de Investigación de Tecnologías de Audio (CITA) of the Institute of Music of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, I am especially grateful to Rodrigo Cádiz, Benjamín Carriquiry, and Paul Magron, for making this experience rich and for their kind help. -

Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: a Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2012 Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: A Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo Brenna C. Halpin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons Recommended Citation Halpin, Brenna C., "Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: A Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo" (2012). Master's Theses. 50. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/50 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (/AV%\ C FLUTES, FESTIVITIES, AND FRAGMENTED TRADITION: A STUDY OF THE MEANING OF MUSIC IN OTAVALO by: Brenna C. Halpin A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty ofThe Graduate College in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Degree ofMaster ofArts School ofMusic Advisor: Matthew Steel, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2012 THE GRADUATE COLLEGE WESTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY KALAMAZOO, MICHIGAN Date February 29th, 2012 WE HEREBY APPROVE THE THESIS SUBMITTED BY Brenna C. Halpin ENTITLED Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: A Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo AS PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE Master of Arts DEGREE OF _rf (7,-0 School of Music (Department) Matthew Steel, Ph.D. Thesis Committee Chair Music (Program) Martha Councell-Vargas, D.M.A. Thesis Committee Member Ann Miles, Ph.D. Thesis Committee Member APPROVED Date .,hp\ Too* Dean of The Graduate College FLUTES, FESTIVITIES, AND FRAGMENTED TRADITION: A STUDY OF THE MEANING OF MUSIC IN OTAVALO Brenna C. -

2018 Available in Carbon Fibre

NFAc_Obsession_18_Ad_1.pdf 1 6/4/18 3:56 PM Brannen & LaFIn Come see how fast your obsession can begin. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Booth 301 · brannenutes.com Brannen Brothers Flutemakers, Inc. HANDMADE CUSTOM 18K ROSE GOLD TRY ONE TODAY AT BOOTH #515 #WEAREVQPOWELL POWELLFLUTES.COM Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 408 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2018 available in Carbon Fibre. Orlando! 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] www.wisemanlondon.com MAKE YOUR MUSIC MATTER Longy has created one of the most outstanding flute departments in the country! Seize the opportunity to study with our world-class faculty including: Cobus du Toit, Antero Winds Clint Foreman, Boston Symphony Orchestra Vanessa Breault Mulvey, Body Mapping Expert Sergio Pallottelli, Flute Faculty at the Zodiac Music Festival Continue your journey towards a meaningful life in music at Longy.edu/apply TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ................................................................ 14 From the Convention Program Chair ................................................. 21 2018 Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished Service Awards ........ 22 Previous Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished -

Musical Origins and the Stone Age Evolution of Flutes

Musical Origins and the Stone Age Evolution of Flutes When we, modern humans, emerged from Africa and colonized Europe Jelle Atema 45,000 years ago, did we have flutes in fist and melodies in mind? Email: [email protected] Introduction Music is an intensely emotional subject and the origins of music have fascinated Postal: people for millennia, going back to early historic records. An excellent review can Boston University be found in “Dolmetsch Online” (http://www.dolmetsch.com/musictheory35. Biology Department htm). Intense debates in the late 19th and early 20th century revolved around the 5 Cummington Street origins of speech and music and which came first. Biologist Charles Darwin, befit- Boston, MA 02215 ting his important recognition of evolution by sexual selection, considered that music evolved as a courtship display similar to bird song; he also felt that speech derived from music. Musicologist Spencer posited that music derived from the emotional content of human speech. The Darwin–Spencer debate (Kivy, 1959) continues unresolved. During the same period the eminent physicist Helmholtz- following Aristotle-studied harmonics of sound and felt that music distinguished itself from speech by its “fixed degree in the scale” (Scala = stairs, i.e. discrete steps) as opposed to the sliding pitches (“glissando”) typical of human speech. As we will see, this may not be such a good distinction when analyzing very early musi- cal instruments with our contemporary bias toward scales. More recent symposia include “The origins of music” (Wallin et al., 2000) and “The music of nature and the nature of music” (Gray et al., 2001). -

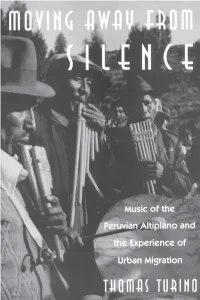

Moving Away from Silence: Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experiment of Urban Migration / Thomas Turino

MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE CHICAGO STUDIES IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY edited by Philip V. Bohlman and Bruno Nettl EDITORIAL BOARD Margaret J. Kartomi Hiromi Lorraine Sakata Anthony Seeger Kay Kaufman Shelemay Bonnie c. Wade Thomas Turino MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experience of Urban Migration THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS Chicago & London THOMAS TURlNo is associate professor of music at the University of Ulinois, Urbana. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1993 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1993 Printed in the United States ofAmerica 02 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 94 93 1 2 3 4 5 6 ISBN (cloth): 0-226-81699-0 ISBN (paper): 0-226-81700-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Turino, Thomas. Moving away from silence: music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the experiment of urban migration / Thomas Turino. p. cm. - (Chicago studies in ethnomusicology) Discography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. I. Folk music-Peru-Conirna (District)-History and criticism. 2. Folk music-Peru-Lirna-History and criticism. 3. Rural-urban migration-Peru. I. Title. II. Series. ML3575.P4T87 1993 761.62'688508536 dc20 92-26935 CIP MN @) The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 239.48-1984. For Elisabeth CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction: From Conima to Lima -

Musical Instruments Inti

MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS INTI - ILLIMANI plays more than 30 wind, string and percussion instruments. In general terms, these instruments belong to the European, American Indian, African and Mestizo cultures which intertwine to form the rich and voluminous musical heritage of the Latin American Continent. INTI - ILLIMANI has carried out permanent tours in the 5 continents, as well as residing in Italy for more than 14 years. On these tours, INTI – ILLIMANI has come into contact with numerous cultures, often integrating their instruments to Inti-Illimani's music. This is the case with the Dulcimer, a string-percussion instrument from the Middle East, which the group integrated in Turkey. A similar situation occurred with the Peruvian Cajon, an instrument of the urban musical culture of Peru. STRING INSTRUMENTS: Guitars, Bass Guitarron Mexicano, Electro Acoustic Bass, Cuatro, Tiple, Charango, Charangon, Mandolin, Paraguay Harp, Hammered Dulcimer, Violin, Viola GUITAR A European instrument adopted by the Latin American population. It is the basic instrument of the Chilean folk music. GUITARRON MEXICANO A mixture of a traditional jazz bass and a guitar, having the structure of a guitar of large dimensions, but which has only 4 strings. CUATRO Instrument of Venezuelan and Colombian origin, with four strings and the resonance case smaller than the guitar. It produces a dry sound. TIPLE Small guitar with a very full sound produced by twelve strings (4 groups of 3). Played mostly in Colombia. CHARANGO The most indigenous of all the guitar-like instruments. It is believed the instrument is a descendant of the guitar, lute or mandolin, and that the Incas of the region known today as Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, part of Argentina and northern Chile, originally made it from a string instrument introduced by the Spaniards. -

Wye---A-History-Of-The-Flute.Pdf

A History of the Flute Trevor Wye 1. Whistles What a daunting prospect to write a simple flute history without missing anything. Looking at a pamphlet a few years ago, it stated that in the South Pacific Islands, those tiny islands south of Hawai, there are about 1300 different named flutes. Our modern flute is just one of thousands of flutes worldwide of all shapes and sizes from miniature ocarinas to giants like the Slovakian Fujara. A sensible way to begin would be to understand how flutes are made to emit sound and so we will look at the four main varieties. These are Endblown where the player blows across the end of the tube; Sideblown as in our modern flute; a Fipple or encapsulated such as is found in a referee's whistle and a Globular flute such as in ocarinas and gemshorns. In all cases, the air is directed against a sharp edge which causes the air to alternate between entering the tube where it meets resistance, then shifting to going outside the tube. This alternation takes place at great speed causing the air inside the tube or vessel to vibrate and so make a sound. In the endblown flute shown below, the tube is held upright and the air directed across the cutaway top of the tube. The fipple flute is sounded by the player directing air through a tube or windway against the sharp edge. An example is the recorder and the pitch is changed by covering the holes down the tube in succession. Globular flutes are sounded either by blowing across a hole or via the fipple which is connected to the 'globe' shown above, though the way the instrument responds is unlike the whistle; the notes can be changed by uncovering any hole, no matter in what position it is placed. -

Entre Sonidos De Bandas De Bronce Y Qina Qina (Quena Quena): Dinámica Musical Y Cultural En Tiwanaku Richard Mújica Angulo1

Museo Nacional de Etnografía y Folklore 159 Entre sonidos de bandas de bronce y Qina Qina (quena quena): dinámica musical y cultural en Tiwanaku Richard Mújica Angulo1 Resumen Esta investigación parte de un enfoque antropológico aplicado al fenómeno musical, donde la transformación cultural tiene un rol central. Un fenómeno contingente motivó este estudio: una banda de música fue incluida en un conjunto musical de Qina Qina, durante la celebración de la fiesta de San Pedro y San Pablo de la localidad aymara de Tiwanaku. Tal evento generó transformaciones en la práctica, representación y producción musical local. Entonces en este texto trabajaré con la siguiente interrogante: ¿cómo se generaron las dinámicas musicales y culturales referidas a la presencia de la banda de música en el Qina Qina de Tiwanaku? Esta presencia visibiliza múltiples procesos de significado, comportamiento y productos sonoros de los grupos e identidades que interpretan esta música-danza-canto. Asimismo, estos procesos son consecuencia de transformaciones en las formas de vida de las actuales comunidades. Así, la presencia de la banda de bronce plantea una constante tensión y lucha de visiones y sentidos del pasado y el presente, donde las identidades tiwanakeñas tienen un rol fundamental. Palabras clave: Dinámica musical, antropología de la música, qina qina, bandas de bronce y Tiwanaku. 1. Introducción al “hallazgo” del tema de investigación Esta investigación es producto de un hallazgo no planificado. El primer encuentro que tuve con los Qina Qina2 de Tiwanaku (localidad aymara ubicada en la prov. Ingavi 1 Licenciado en Antropología por la Universidad Mayor de San Andrés (UMSA), maestrante en Estudios Críticos del Desarrollo en el Postgrado en Ciencias del Desarrollo de la Universidad Mayor de San Andrés (CIDES-UMSA), investigador de Pacha Kamani: espacio Intercultural de Práctica e Investigación Ancestral. -

The Kantu Ensemble of the Kallawa Ya at Charazani (Bolivia)

THE KANTU ENSEMBLE OF THE KALLAWA YA AT CHARAZANI (BOLIVIA) by Max Peter Baumann The Kallawaya belang to the Quechua-speaking population of Bolivia and live on the eastern slope of the Andes in the Charazani valley system, north of Lake Titicaca, near the Peruvian border. Located in the Bautista Saavedra province of the Department of La Paz, the Valley and Rio Charazani cut across the Cordilleras and thus serve as a gateway to the lower-lying Yungas to the east. The Incas in their heyday prized this valley highly, for it lay at the outermost Iimits of their empire's expansion and opened into areas where the coca plant and tropical fruits and herbs were grown. Because of the alkaloids it contains, the coca plant (Eritroxilon Coca L.) has played an important role in rituals and cult practices since pre-Spanish times (M. Wendorf de Sejas 1982:223; J.W. Bastien 1978:19). The Kallawaya people have been known since antiquity as herbalists and healers, and the Incas are said to have accorded them special privileges on this account: Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala teils in his "Nueva Cor6nica y Buen Gobierno" from about 1600 of "Callauayas" carrying Inca Tupac Yupanqui (1471-1493) and his wife Mama Occlo-Coya in a sedan chair at the Cuzcan court (F. Guaman Poma, ed. 1936: fol. 331). The origin of the name Kallawaya has not yet been completely explained. The entire population of the Charazani Valley is often referred to as Kallawaya, but in its narrower sense the term designates the herbalists, who on their wanderings into remote areas speak an esoteric and magical ritual language, Kallawaya or Macchaj-juyai (E. -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality. -

Music Andean Altiplano

Music oject of the Andean Altiplano Goals 2000 - Partnerships for Educating Colorado Students In Partnership with the Denver Public Schools and the Metropolitan State College of Denver El Alma de la Raza Pr El Music of the Andean Altiplano by Deborah Hanley Grades 4–8 Implementation Time for Unit of Study: 3 weeks Goals 2000 - Partnerships for Educating Colorado Students El Alma de la Raza Curriculum and Teacher Training Project El Alma de la Raza Series El Loyola A. Martinez, Project Director Music of the Andean Altiplano Unit Concepts • Composing music, performing, and building siku pipes • Investigating the music of Quechua and Aymara communities • Learning about the professional lives of two Denver musicians who perform on these instruments Standards Addressed by This Unit Music Students sing or play on instruments a varied repertoire of music, alone or with others. (MUS1) Students will read and notate music. (MUS2) Students will create music. (MUS3) Students will listen to, analyze, evaluate, and describe music. (MUS4) Students will relate music to various historical and cultural traditions. (MUS5) Math Students use a variety of tools and techniques to measure, apply the results in problem- solving situations, and communicate the reasoning used in solving these problems. (M5) Visual Arts Students know and apply visual arts materials, tools, techniques, and processes. (A3) Reading and Writing Students read and understand a variety of materials. (RW1) History Students understand that societies are diverse and have changed over time. (H3) Geography Students know how to use and construct maps, globes, and other geographic tools to locate and derive information about people, places, and environments.