Pleading Wizard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photograph by Candace Dicarlo

60 MAY | JUNE 2013 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE PHOTOGRAPH BY CANDACE DICARLO Showtime CEO Matt Blank has used boundary-pushing programming, cutting-edge marketing, and smart management to build his cable network into a national powerhouse. By Susan Karlin SUBVERSIVE PRACTICALLY PRACTICALLY THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE MAY | JUNE 2013 61 seems too … normal. “Matt runs the company in a very col- Showtime, Blank is involved with numer- This slim, understated, affa- legial way—he sets a tone among top man- ous media and non-profit organizations, Heble man speaking in tight, agers of cooperation, congeniality, and serving on the directing boards of the corporate phrases—monetizing the brand, loose boundaries that really works in a National Cable Television Association high-impact environments—this can’t be creative business,” says David Nevins, and The Cable Center, an industry edu- the guy whose whimsical vision has Showtime’s president of entertainment. cational arm. Then there are the frequent turned Weeds’ pot-dealing suburban “It helps create a sense of, ‘That’s a club trips to Los Angeles. mom, Dexter’s vigilante serial killer, and that I want to belong to.’ He stays focused “I’m an active person,” he adds. “I like Homeland’s bipolar CIA agent into TV on the big picture, maintaining the integ- a long day with a lot of different things heroes. Can it? rity of the brand and growing its exposure. going on. I think if I sat in a room and did Yet Matt Blank W’72, the CEO of Showtime, Matt is very savvy at this combination of one thing all day, I’d get frustrated.” has more in common with his network than programming and marketing that keeps his conventional appearance suggests. -

“Russet Potatoes” Written by Ashley Gable Directed by Norberto Barba

“Russet Potatoes” Written by Ashley Gable Directed by Norberto Barba Episode 117 #3T7817 Warner Bros. Entertainment PRODUCTION DRAFT 4000 Warner Blvd. February 2, 2009 Burbank, CA 91522 FULL BLUE 2/03/09 FULL PINK 2/04/09 FULL YELLOW 2/05/09 GREEN REVS. 2/09/09 GOLD REVS. 2/11/09 SALMON REVS. 3/09/09 CHERRY REVS. 3/09/09 GRAY REVS. 3/13/09 © 2009 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. This script is the property of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. No portion of this script may be performed, reproduced or used by any means, or disclosed to, quoted or published in any medium without the prior written consent of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. THE MENTALIST “Russet Potatoes” Episode #117 March 13, 2009 – Gray Revisions REVISED PAGES GREEN REVISIONS – 2/09/09 7, 8, 52 GOLD REVISIONS – 2/11/09 1, 2, 21, 30, 30A, 30B SALMON REVISIONS – 3/09/09 26, 26A, 26B, 39, 39A, 39B, 39C CHERRY REVISIONS – 3/09/09 26B GRAY REVISIONS – 3/13/09 26, 26A, 26B TEASER FADE IN: 1 EXT. STREET. DOWNTOWN SACRAMENTO - DAY (D/1) 1 Morning. Everyone’s heading to work, ready or not. On the sidewalks a sea of corporate drones, tight-skirted assistants, power-suited attorneys -- And CARL RESNICK, late 20’s, a schlub with a please-don’t- hurt-me air. But today, a determined schlub, a schlub with a mission. He plows through the crowd dragging something heavy -- maybe he’s got a large suitcase, maybe his bike lost a tire, we can’t tell. Carl’s puffing a self-help mantra -- CARL ...Self isn’t something you find, it’s something you create. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16 A70 TV Acad Ad.Qxp Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16_A70_TV_Acad_Ad.qxp_Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1 PROUD MEMBER OF »CBS THE TELEVISION ACADEMY 2 ©2016 CBS Broadcasting Inc. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER AS THE QUANTITY AND QUALITY OF CONTENT HAVE INCREASED in what is widely regarded as television’s second Golden Age, so have employment opportunities for the talented men and women who create that programming. And as our industry, and the content we produce, have become more relevant, so has the relevance of the Television Academy increased as an essential resource for television professionals. In 2015, this was reflected in the steady rise in our membership — surpassing 20,000 for the first time in our history — as well as the expanding slate of Academy-sponsored activities and the heightened attention paid to such high-profile events as the Television Academy Honors and, of course, the Creative Arts Awards and the Emmy Awards. Navigating an industry in the midst of such profound change is both exciting and, at times, a bit daunting. Reimagined models of production and distribution — along with technological innovations and the emergence of new over-the-top platforms — have led to a seemingly endless surge of creativity, and an array of viewing options. As the leading membership organization for television professionals and home to the industry’s most prestigious award, the Academy is committed to remaining at the vanguard of all aspects of television. Toward that end, we are always evaluating our own practices in order to stay ahead of industry changes, and we are proud to guide the conversation for television’s future generations. -

Shon Hedges Editor

SHON HEDGES EDITOR FEATURES iGILBERT Paloma Pictures Prod: Cynthia Hargrave, Adrian Martinez Dir: Adrian Martinez Anthony Vorhies PICTURE PARIS (Short) For Goodness Sake Prod: Brad Hall, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Julie Snyder Dir: Brad Hall *Official Selection, Tribeca Film Festival, 2012 GENEROSITY OF EYE (Documentary) For Goodness Sake Prod: Brad Hall, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Julie Snyder Dir: Brad Hall ABOUT SUNNY (Associate Editor) On the Line Prods./ Prod: Lauren Ambrose, Blythe Robertson, Mike Ryan Dir: Bryan Wizemann Votiv Films AFRICAN ADVENTURE: nWave Pictures Prod: Ben Stassen Dir: Ben Stassen SAFARI IN THE OKAVANGO (Documentary) TELEVISION NEW AMSTERDAM (Season 1) Universal/NBC Prod: Peter Horton, David Schulner Dir: Various THE ORVILLE (Season 1) 20th Century Fox/Fox Prod: Seth McFarlane, David Goodman Dir: Various Brannon Braga, John Cassar BULL (Season 1) CBS Studios/CBS Prod: Mark Goffman, Paul Attanasio Dir: Various BLACK SAILS (Ep. 106, 209, 302) Starz Prod: Michael Bay, Jonathan Steinberg, Dan Shotz Dir: T.J. Scott, Lukas Ettlin HEROES REBORN (Season 1) Universal/NBC Prod: Tim Kring, Lori Motyer Dir: Various HOMELAND (Season 2) Fox 21/Showtime Prod: Alex Gansa, Meredith Stiehm, Howard Gordon Dir: Various (Additional Editing) THE KILLING (Season 2) Fox TV/AMC/Netflix Prod: Veena Sud, Mikkel Bondesen, Ron French Dir: Various (Assistant Editor) SMASH (Pilot) (Assistant Editor) Universal/NBC Prod: Justin Falvey, Darryl Frank, Marc Shaiman Dir: Michael Mayer IN PLAIN SIGHT (Ep. 403) USA Prod: David Maples Dir: Michael Schultz (Assistant Editor) IN TREATMENT (Ep. 326, 327, 328) HBO Prod: Paris Barclay, Anya Epstein Dir: Various (Assistant Editor) RUBICON (Season 1) Warner Horizon/AMC Prod: Henry Bromwell, Jason Horwitch Dir: Various (Assistant Editor) A MARRIAGE (Pilot) CBS Prod: Ed Zwick, Marshall Herzkovitz Dir: Marshall Herskovitz QUARTERLIFE (3 episodes) NBC Prod: Ed Zwick, Marshall Herzkovitz Dir: Marshall Herskovitz, Catherine Jelski 405 S Beverly Drive, Beverly Hills, California 90212 - T 310.888.4200 - F 310.888.4242 www.apa-agency.com . -

TV Outside The

1 ALPHA HOUSE on Amazon Elliot Webb: Executive Producer As trailblazers in the television business go, Garry Trudeau, the iconic, Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist/creator of Doonesbury, has an unprecedented track record. In 1988, Trudeau wrote and co-produced (with director Robert Altman) the critically acclaimed, political mockumentary Tanner ’88 for HBO. It was HBO’s first foray into the original scripted TV business, albeit for a limited series. (9 years later, in 1997, Oz became HBO’s first scripted drama series.) Tanner ’88 won an Emmy Award and 4 cable ACE Awards. 25 years later, Trudeau created Alpha House—which holds the distinction of being the very first original series on Amazon. The single-camera, half-hour comedy orbits around the exploits of four Republican senators (played by John Goodman, Clark Johnson, Matt Malloy, and Mark Consuelos) who live as roommates in the same Capitol Hill townhouse. The series was inspired by actual Democratic congressmen/roomies: Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL), Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY), and Representative George Miller (D-CA). Bill Murray did 2 cameos as hapless Senator Vernon Smits. Other real life politicians appeared throughout the series’ 2- season run. The series follows in the footsteps of Lacey Davenport (the Doonesbury Republican congresswoman from San Francisco), and presidential candidate Jack Tanner (played by Michael Murphy). All of Trudeau’s politicians are struggling to reframe their platforms and priorities while their parties are in flux. I think it’s safe to say that the more things change in Washington, the more things stay the same. Trudeau explores identity crises through his trademark trenchant humor. -

Homeland Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HOMELAND PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Fernando Aramburu | 640 pages | 02 Apr 2020 | Pan MacMillan | 9781509858040 | English | London, United Kingdom Homeland PDF Book At eight seasons long, Homeland is already Showtime's second-longest running drama behind Shameless , which premiered nine months before Homeland. Watch on Prime Video included with Prime. With the help of her long-time mentor Saul Berenson Mandy Patinkin , Carrie fearlessly risks everything, including her personal well-being and even sanity, at every turn. Laura Played by Sarah Sokolovic A bright American journalist who works for the same organization as Carrie in Berlin, Laura ends up on the receiving end of some highly classified leaked information that has the potential to devastate U. Trivia Graffiti artists employed to create slogans for a refugee camp in season five actually wrote anti-Homeland slogans such as "Homeland is a joke, and it didn't make us laugh" on the set in protest at the show's portrayal of Muslims. Alex Gansa and Howard Gordon, along with an excellent team of writers, producers, and directors the latter of which was led by the great Lesli Linka Glatter , refused to provide solutions to problems without any. The entire last season, and certainly, the last episode, was geared for those people that have been with the show. The mastermind of an attack on the American Embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan that killed 36 Americans, Haqqani is now the head of the Taliban. Wolf was in the chief role at the department in an acting capacity for 14 months. I mean, it was just beyond emotional. -

Sesiune Speciala Intermediara De Repartitie - August 2018 DACIN SARA Aferenta Difuzarilor Din Perioada 01.04.2008 - 31.03.2009

Sesiune speciala intermediara de repartitie - August 2018 DACIN SARA aferenta difuzarilor din perioada 01.04.2008 - 31.03.2009 TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 A1 A2 3:00 a.m. 3 A.M. 2001 US Lee Davis Lee Davis 04:30 04:30 2005 SG Royston Tan Royston Tan Liam Yeo 11:14 11:14 2003 US/CA Greg Marcks Greg Marcks 1941 1941 1979 US Steven Bob Gale Robert Zemeckis (Trecut, prezent, viitor) (Past Present Future) Imperfect Imperfect 2004 GB Roger Thorp Guy de Beaujeu 007: Viitorul e in mainile lui - Roger Bruce Feirstein - 007 si Imperiul zilei de maine Tomorrow Never Dies 1997 GB/US Spottiswoode ALCS 10 produse sau mai putin 10 Items or Less 2006 US Brad Silberling Brad Silberling 10.5 pe scara Richter I - Cutremurul I 10.5 I 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 10.5 pe scara Richter II - Cutremurul II 10.5 II 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 100 milioane i.Hr / Jurassic in L.A. 100 Million BC 2008 US Griff Furst Paul Bales 101 Dalmatians - One Hamilton Luske - Hundred and One Hamilton S. Wolfgang Bill Peet - William 101 dalmatieni Dalmatians 1961 US Clyde Geronimi Luske Reitherman Peed EG/FR/ GB/IR/J Alejandro Claude Marie-Jose 11 povesti pentru 11 P/MX/ Gonzalez Amos Gitai - Lelouch - Danis Tanovic - Alejandro Gonzalez Amos Gitai - Claude Lelouch Danis Tanovic - Sanselme - Paul Laverty - Samira septembrie 11'09''01 - September 11 2002 US Inarritu Mira Nair SACD SACD SACD/ALCS Ken Loach Sean Penn - ALCS -

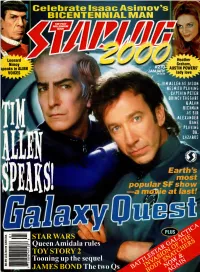

Starlog Magazine

Celebrate Isaac Asimov's BICENTENNIAL MAN 2 Leonard * V Heather Nimoy Graham, speaks in ALIEN — AUSTIN POWERS' VOICES lady love 1 40 (PIUS) £>v < -! STAR WARS CA J OO Queen Amidala rules o> O) CO TOY STORY 2 </) 3 O) Tooning up the sequel ft CD GO JAMES BOND The two Q THE TRUTH If you're a fantasy sci-fi fanatic, and if you're into toys, comics, collectibles, Manga and anime. if you love Star Wars, Star Trek, Buffy, Angel and the X-Files. Why aren't you here - WWW.ign.COtH mm INSIDE TOY STORY 2 The Pixarteam sends Buzz & Woody off on adventure GALAXY QUEST: THE FILM Questarians! That TV classic is finally a motion picture HEROES OF THE GALAXY Never surrender these pin- ups at the next Quest Con! METALLIC ATTRACTION Get to know Witlock, robot hero & Trouble Magnet ACCORDING TO TIM ALLEN He voices Buzz Lightyear & plays the Questarians' favorite commander THAT HEROIC GUY Brendan Fraser faces mum mies, monsters & monkeys QUEEN AMIDALA RULES Natalie Portman reigns against The Phantom Menace THE NEW JEDI ORDER Fantasist R.A. Salvatore chronicles the latest Star Wars MEMORABLE CHARACTER Now & Again, you've seen actor ! Cerrit Graham 76 THE SPY WHO SHAGS WELL Heather Graham updates readers STARLOC: The Science Fiction Universe is published monthly by STARLOG GROUP, INC., 475 Park Avenue South, New York, on her career moves NY 10016. STARLOG and The Science Fiction Universe are registered trademarks of Starlog Group Inc' (ISSN 0191-4626) (Canadian GST number: R-124704826) This is issue Number 270, January 2000. -

For Immediate Release

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACTS: Jill Tewsley - 231-577-6971 or jtewsley@ nwstc.org Susan Wilcox Olson (231) 590-5930 [email protected] IN ADDITION TO ITS ALL-STAR LINE-UP OF VISITING AUTHORS THE JUST-ANNOUNCED NATIONAL WRITERS SERIES SEASON TO FEATURE LITERARY LUMINARIES MAKING RARE U.S. ONSTAGE APPEARANCES AS GUESTS HOSTS. Guest hosts include luminary editors, book reviewers, and publishing professionals from across the United States: NWS Newsweek/The Daily Beast books editor Lucas Wittmann; award-winning Detroit News columnist Neal Rubin; O, The Oprah Magazine books editor Leigh Haber; groundbreaking Byliner.com editor Laura Hohnhold; Bibliostar.tv creator Rich Fahle; and NWS co-founder and New York Times bestselling author Doug Stanton. Traverse City, Mich. – February 20, 2013 The National Writers Series unveiled their 2013 Winter Spring line-up during their first event of year with writer and executive producer Chip Johannessen, of Showtime’s Homeland television show, on February 7. The slate of eight eclectic shows is selling extremely quickly to ticket holders from around the Midwest, and response to the amazing roster of guests-- Buzz Bissinger, Blaine Harden, Gillian Flynn, Nathaniel Philbrick, Jason Matthews, Colum McCann, and Temple Grandin-- has been loud and clear: we love meeting authors at NWS. Equally interesting and exciting has been audience response to the events’ guests hosts, a stellar line-up of fascinating reviewers, publishers, and publishing professionals. “We spend a lot of time thinking about guests and hosts and creating what we hope will be a moving and entertaining conversation onstage, and these events, with these guest hosts, are basically an evening up close with two literary stars at once. -

Sundance Institute Unveils Latest Episodic Story Lab Fellows

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: September 20, 2016 Spencer Alcorn 310.360.1981 [email protected] Sundance Institute Unveils Latest Episodic Story Lab Fellows 11 New Television Pilots Selected from 2,000 Submissions Projects Include Tudor-Era Family Comedy, Mysterious Antarctic Anomaly, Animated Greek Gods and More Rafael Agustin, Nilanjana Bose, Jakub Ciupinski, Mike Flynn, Eboni Freeman, Hilary Helding, Donald Joh; John McClain, Colin McLaughlin, Jeremy Nielsen, Connie O’Donahue, Calvin Lee Reeder, Marlena Rodriguez. Los Angeles, CA — Sundance Institute today announced the 11 original projects selected for its third annual Episodic Story Lab. The spec pilots, which range from dystopian sci-fi to historical comedy, explore themes of personal and social identity, family dysfunction, political extremism, and the limits of human understanding. The Episodic Story Lab is the centerpiece of the Institute’s year-round support program for emerging television writers. During the Lab, the 13 selected writers (the “Fellows”) will participate in individual and group creative meetings, writers’ rooms, case study screenings, and pitch sessions to further develop their pilot scripts with guidance from accomplished showrunners, producers and television executives. Beginning with the Lab, Fellows will benefit from customized, ongoing support from Feature Film Program staff, Creative Advisors and Industry Mentors, led by Founding Director of the Sundance Institute Feature Film Program, Michelle Satter, and Senior Manager of the Episodic -

Challenging Stereotypes

Challenging Stereotypes How the stereotypical portrayals of Muslims and Islam are challenged through the enemies in Homeland Gunhild-Marie Høie A Thesis Presented to the Departure of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the MA degree University of Oslo Spring 2014 I II Challenging Stereotypes How the stereotypical portrayals of Muslims and Islam are challenged through the enemies in Homeland Gunhild-Marie Høie A Thesis Presented to the Departure of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the MA degree University of Oslo Spring 2014 III © Gunhild-Marie Høie 2014 Challenging Stereotypes: How the stereotypical portrayals of Muslims and Islam are challenged in Homeland. http://www.duo.uio.no Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo IV V Abstract Following the terrorist attack on 9/11, actions and practices of the United States government, as well as the dominant media discourse and non-profit media advertising, contributed to create a post-9/11 climate in which Muslims and Arabs were viewed as non-American. This established a binary paradigm between Americans and Muslims, where Americans represented “us” whereas Muslims represented “them.” Through a qualitative analysis of the main characters in the post-9/11 terrorism-show, Homeland, season one (2011), as well as an analysis of the opening sequence and the overall narrative in the show, this thesis argues that this binary system of “us” and “them” is no longer black and white, but blurred, and hard to define. My analysis indicates that several of the enemies in the show break with the stereotypical portrayal of Muslims as crude, violent fanatics. -

From the Nordic Police Procedural to American Border Drama Karima Thomas

From the Nordic police procedural to American Border Drama Karima Thomas To cite this version: Karima Thomas. From the Nordic police procedural to American Border Drama. Représentations dans le monde anglophone, CEMRA, 2017, pp.144-169. hal-02616239 HAL Id: hal-02616239 https://hal.univ-angers.fr/hal-02616239 Submitted on 24 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Représentations dans le monde anglophone – Janvier 2017 From the Nordic police procedural to American Border Drama Karima Thomas, IUT d’Angers Keywords: border drama, adaptation, Nordic drama, subversion, genre bending. Mots-clés: films des frontières, le policier nordique, adaptation, transformations générique. Analyzing “genre bending” in remakes presupposes that genres in entertainment television are uniform and consistent formulas with delimited frontiers. Unlike literary genres, genres in TV series are determined by aesthetic, ideological and commercial factors. Jason Mittell accounts for the difficulty of generic definitions by the fact that genres in entertainment TV can be defined by a broad range of criteria (235). He goes as far as considering genre as a mere taxonomic shortcut meant to make a program fit in a time slot and therefore to ensure distribution and to appeal to a target audience1.