The Thermal Dehydration of Natural Zeolites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Regional Distribution of Zeolites in the Basalts of the Faroe Islands and the Significance of Zeolites As Palaeo- Temperature Indicators

The regional distribution of zeolites in the basalts of the Faroe Islands and the significance of zeolites as palaeo- temperature indicators Ole Jørgensen The first maps of the regional distribution of zeolites in the Palaeogene basalt plateau of the Faroe Islands are presented. The zeolite zones (thomsonite-chabazite, analcite, mesolite, stilbite-heulandite, laumontite) continue below sea level and reach a depth of 2200 m in the Lopra-1/1A well. Below this level, a high temperature zone occurs characterised by prehnite and pumpellyite. The stilbite-heulan- dite zone is the dominant mineral zone on the northern island, Vágar, the analcite and mesolite zones are the dominant ones on the southern islands of Sandoy and Suðuroy and the thomsonite-chabazite zone is dominant on the two northeastern islands of Viðoy and Borðoy. It is estimated that zeolitisa- tion of the basalts took place at temperatures between about 40°C and 230°C. Palaeogeothermal gradients are estimated to have been 66 ± 9°C/km in the lower basalt formation of the Lopra area of Suðuroy, the southernmost island, 63 ± 8°C/km in the middle basalt formation on the northernmost island of Vágar and 56 ± 7°C/km in the upper basalt formation on the central island of Sandoy. A linear extrapolation of the gradient from the Lopra area places the palaeosurface of the basalt plateau near to the top of the lower basalt formation. On Vágar, the palaeosurface was somewhere between 1700 m and 2020 m above the lower formation while the palaeosurface on Sandoy was between 1550 m and 1924 m above the base of the upper formation. -

Mineral Processing

Mineral Processing Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy 1st English edition JAN DRZYMALA, C. Eng., Ph.D., D.Sc. Member of the Polish Mineral Processing Society Wroclaw University of Technology 2007 Translation: J. Drzymala, A. Swatek Reviewer: A. Luszczkiewicz Published as supplied by the author ©Copyright by Jan Drzymala, Wroclaw 2007 Computer typesetting: Danuta Szyszka Cover design: Danuta Szyszka Cover photo: Sebastian Bożek Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej Wybrzeze Wyspianskiego 27 50-370 Wroclaw Any part of this publication can be used in any form by any means provided that the usage is acknowledged by the citation: Drzymala, J., Mineral Processing, Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy, Oficyna Wydawnicza PWr., 2007, www.ig.pwr.wroc.pl/minproc ISBN 978-83-7493-362-9 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................9 Part I Introduction to mineral processing .....................................................................13 1. From the Big Bang to mineral processing................................................................14 1.1. The formation of matter ...................................................................................14 1.2. Elementary particles.........................................................................................16 1.3. Molecules .........................................................................................................18 1.4. Solids................................................................................................................19 -

Studies of the Zeolites Composition of Zeolites of the Natrolite Group and Compositional Relations Among Thomsonites Gonnardites, and Natrolites

r-'1 ~ Q I ~ c lt') ~ r-'1 'JJ ~ Q.) < ~ ~ ......-~ ..,.;;j ~ <z 0 0 Q.) 1-4 rJ:J rJ:J N r-'1 ~ Q.) 0 ~ ..c ~ ~ ~ I r-'1 ~ > ~ 0 I ~ rJ:J 'JJ ..,.;;j Q.) < .....-~ 0 . 1-4 ~ C"-' 0 ~ ..,.;;j ~ 0 r-'1 00 C"-' Foster-STUDIES•. OF THE ZEOLITES-Geological Survey Professional Paper 504-D, E Studies of the Zeolites Composition of Zeolites of the Natrolite Group and Compositional Relations among Thomsonites Gonnardites, and Natrolites By MARGARET D. FOSTER SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 504-D, E UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1965 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretory GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U.S. Geological Survey Library has cataloged this publication as follows: Foster, Margaret Dorothy, 1895- Studies of the zeolites. D. Composition of zeolites of the natrolite group. E. Compositional relations among thom sonites, gonnardites, and natrolites. Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1965. v, 7; iii, 10 p. diagrs., tables. 30 em. (U.S. Geological Survey. Professional paper 504-D, E) Shorter contributions to general geology. Each part also has separate title page. Includes bibliographies. (Continued on next card) Foster, Margaret Dorothy, 1895- Studies of the zeolites. 1965. (Card 2) 1. Zeolites. I. Title. II. Title: Composition of zeolites of the natro lite group. III. Title: Compositional relations among thomsonites, gonnardites, and natrolites. (Series) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 25 cents (paper cover) Studies of the Zeolites Composition of Zeolites of the N atrolite Group By MARGARET D. -

Gonnardite Na2caal4si6o20 ² 7H2O C 2001 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1.2 ° Crystal Data: Tetragonal

Gonnardite Na2CaAl4Si6O20 ² 7H2O c 2001 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1.2 ° Crystal Data: Tetragonal. Point Group: 42m: Fibrous crystals, at the centers of radiating spherulites, to 3 cm; massive. Physical Properties: Hardness = 5 D(meas.) = 2.25{2.36 D(calc.) = 2.33 Optical Properties: Translucent. Color: White, yellowish to salmon-red. Luster: Silky. Optical Class: Biaxial (+) or ({); commonly zoned. Orientation: X = c. ® = 1.497{1.508 ¯ = 1.498{1.510 ° = 1.499{1.513 2V(meas.) = 50± Cell Data: Space Group: I42d: a = 13.21(1) c = 6.622(4) Z = 2 X-ray Powder Pattern: Chaux de Bergonne, France; may be confused with natrolite and tetranatrolite. 2.92 (100), 5.93 (80), 6.70 (60), 4.44 (60), 4.74 (50), 3.23 (50), 3.12 (40) Chemistry: (1) (2) (3) SiO2 43.45 43.20 44.58 Al2O3 27.91 27.90 25.22 CaO 6.95 3.61 6.94 Na2O 8.69 13.16 7.66 H2O [13.00] 11.74 15.60 Total [100.00] 99.61 100.00 (1) Chaux de Bergonne, France; by electron microprobe, H2O by di®erence; corresponding to Na2:22Ca0:98Al4:32Si5:71O20 ² 5:70H2O: (2) Aci Trezza, Sicily, Italy; corresponds to Na3:5Ca0:5Al4:5 Si5:9O20:8 ² 5:35H2O: (3) Na2CaAl4Si6O20 ² 7H2O: Mineral Group: Zeolite group. Occurrence: In cavities in basalt, leucite tephrite, and altered skarn. Association: Zeolites, calcite. Distribution: Well characterized material from: in France, at Chaux de Bergonne, Gignat, Puy de D^ome. In Italy, from Capo di Bove, near Rome, Lazio; and at Aci Castello, Aci Trezza, Osilo, and other places on Sardinia. -

THE CRYSTAL STRUCTURE of CAHNITE, Cabaso4 (OH)4

THE CRYSTAL STRUCTURE OF CAHNITE, CaBAsO4 (OH)4 by Charles T. Prewitt S.B., M.I.T.AAT.rc (1955) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL YULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (1960) Signature of Author .,. ..... .. ... .... Department of>Geolgy nd Geophysics, May 20, 1960 Certified by . t -.. 4-w.Vi 4 ... .. ... , . Thesis Supervisor Accepted by . .* . .... ... Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students THE CRYSTAL STRUCTURE OF CAHNITE, Ca2 BAs04 (OH)4 Charles T. Prewitt Submitted to the Department of Geology on May 20, 1960 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. Cahnite is one of the few crystals which had been assigned to crystal class 4. A precession study showed that its diffraction sphol is 4/m I-/-, which contains space groups I4, I4E, and14/. Because of the known 4 morphology, it must be assigned to space group I4. The unit cell, whose dimensions are a = 7.11A, o = 6.201, contains two formula weights of Ca BAsO (OH)L. The structure was studied with the aid of in ensity medsurements made with a single-crystal diffractometer. Patterson s ntheses were first made for projections along the c, a, and 110 directions. The atomic numbers of the atoms are in the ratio As:Ca.0:B = 33:20:8:5, so that the Patterson peaks are dominated by the atom pairs containing arsenic as one member of the pair. Since there are only two arsenic atoms in a body-centered cell, one As can be arbitrarily assigned to the origin. -

New Minerals Approved Bythe Ima Commission on New

NEW MINERALS APPROVED BY THE IMA COMMISSION ON NEW MINERALS AND MINERAL NAMES ALLABOGDANITE, (Fe,Ni)l Allabogdanite, a mineral dimorphous with barringerite, was discovered in the Onello iron meteorite (Ni-rich ataxite) found in 1997 in the alluvium of the Bol'shoy Dolguchan River, a tributary of the Onello River, Aldan River basin, South Yakutia (Republic of Sakha- Yakutia), Russia. The mineral occurs as light straw-yellow, with strong metallic luster, lamellar crystals up to 0.0 I x 0.1 x 0.4 rnrn, typically twinned, in plessite. Associated minerals are nickel phosphide, schreibersite, awaruite and graphite (Britvin e.a., 2002b). Name: in honour of Alia Nikolaevna BOG DAN OVA (1947-2004), Russian crys- tallographer, for her contribution to the study of new minerals; Geological Institute of Kola Science Center of Russian Academy of Sciences, Apatity. fMA No.: 2000-038. TS: PU 1/18632. ALLOCHALCOSELITE, Cu+Cu~+PbOZ(Se03)P5 Allochalcoselite was found in the fumarole products of the Second cinder cone, Northern Breakthrought of the Tolbachik Main Fracture Eruption (1975-1976), Tolbachik Volcano, Kamchatka, Russia. It occurs as transparent dark brown pris- matic crystals up to 0.1 mm long. Associated minerals are cotunnite, sofiite, ilin- skite, georgbokiite and burn site (Vergasova e.a., 2005). Name: for the chemical composition: presence of selenium and different oxidation states of copper, from the Greek aA.Ao~(different) and xaAxo~ (copper). fMA No.: 2004-025. TS: no reliable information. ALSAKHAROVITE-Zn, NaSrKZn(Ti,Nb)JSi401ZJz(0,OH)4·7HzO photo 1 Labuntsovite group Alsakharovite-Zn was discovered in the Pegmatite #45, Lepkhe-Nel'm MI. -

Carbonatites of the World, Explored Deposits of Nb and REE—Database and Grade and Tonnage Models

Carbonatites of the World, Explored Deposits of Nb and REE—Database and Grade and Tonnage Models By Vladimir I. Berger, Donald A. Singer, and Greta J. Orris Open-File Report 2009-1139 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod/ Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation: Berger, V.I., Singer, D.A., and Orris, G.J., 2009, Carbonatites of the world, explored deposits of Nb and REE— database and grade and tonnage models: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2009-1139, 17 p. and database [http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2009/1139/]. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. ii Contents Introduction 1 Rules Used 2 Data Fields 2 Preliminary analysis: —Grade and Tonnage Models 13 Acknowledgments 16 References 16 Figures Figure 1. Location of explored Nb– and REE–carbonatite deposits included in the database and grade and tonnage models 4 Figure 2. Cumulative frequency of ore tonnages of Nb– and REE–carbonatite deposits 14 Figure 3 Cumulative frequency of Nb2O5 grades of Nb– and REE–carbonatite deposits 15 Figure 4 Cumulative frequency of RE2O3 grades of Nb– and REE–carbonatite deposits 15 Figure 4 Cumulative frequency of P2O5 grades of Nb– and REE–carbonatite deposits 16 Tables Table 1. -

10Са9(Fе3+,Fе2+)

Расцветаева Р. К., Пущаровский Д Ю., Виноградова Р. А. , Леков И. В. Кристаллическая структу- ра дашкесанита // Кристаллография. 1996. Т. 41. ](2 1. С. 65-69. Чуканов Н. В., Конилов А. Н., Задов А. Е., Белаковский Д и., Леков И. В. НОВЫЙ амфибол калие- вый хлоропаргасит и условия его формирования в гранулитовом комплексе Сальных тундр (Кольский полуостров) // ЗВМО. 2002. N~2. С. 58-61. Burke Е. А. J, Leake В. Е. «Named Amphiboles», а new category of amphiboles recognized Ьу the [гпег- national Mineralogical Association (lMA) and the ргорег order of prefixes to Ье used in amphibole names /1 Canad. Miner. 2004. Yol. 42. Р. 1881-1883. Jacobson S. S. Dashkesanite: high-chlorine amphibole from St. Paul's rock, Equatorial Atlantic and Transcaucasia, USSR 11 Smithson. Contrib. Earth Sci. 1975. Yol. 14. Р. 17-20. Leake В. Е. Nomenclature of amphiboles 11Amer. Мшег, 1978. Уоl. 63. Р. 1025-1052. Leake В. Е. е. а. Nomenclature ofamphiboles: Report ofthe subcommittee оп amphiboles ofthe Intemati- опа! Mineralogical Association, Commission оп New Minerals and Mineral Names 11Canad. Miner. 1997. Уоl. 35. Р. 219-246. Leake В. Е. е. а. Nomenclature of amphiboles: additions and revisions to the Intemational Mineralogical Association's amphibole nomenclature 11Canad. Miner. 2003. Yol. 41. Р. 1355-1362. Nickel Е. н., Mandarino J. А. Procedures involving the IMA Commission оп New Minerals and Mineral Names, and guidelines оп mineral nomenclature 11 Canad. Miner. 1987. Уо1. 25. Р. 353-377. Oberti R., Ungaretti L., СаnnШо Е., Hawthorne F. С. The mechanism of chlor incorporation in атпрпйю- lе 11Amer. Miner. 1993. Yol. 78. -

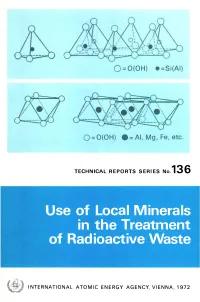

Use of Local Minerals in the Treatment of Radioactive Waste

O = 0(0H) •=Si(AI) O = 0(0H) # = AI, Mg, Fe, etc. TECHNICAL REPORTS SERIES No. 136 Use of Local Minerals in the Treatment of Radioactive Waste INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, VIENNA, 1972 USE OF LOCAL MINERALS IN THE TREATMENT OF RADIOACTIVE WASTE The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN GUATEMALA PAKISTAN ALBANIA HAITI PANAMA ALGERIA HOLY SEE PARAGUAY ARGENTINA HUNGARY PERU AUSTRALIA ICELAND PHILIPPINES AUSTRIA INDIA POLAND BELGIUM INDONESIA PORTUGAL BOLIVIA IRAN ROMANIA BRAZIL IRAQ SAUDI ARABIA BULGARIA IRELAND SENEGAL BURMA ISRAEL SIERRA LEONE BYELORUSSIAN SOVIET ITALY SINGAPORE SOCIALIST REPUBLIC IVORY COAST SOUTH AFRICA CAMEROON JAMAICA SPAIN CANADA JAPAN SUDAN CEYLON JORDAN SWEDEN CHILE KENYA SWITZERLAND CHINA KHMER REPUBLIC SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC COLOMBIA KOREA, REPUBLIC OF THAILAND COSTA RICA KUWAIT TUNISIA CUBA LEBANON TURKEY CYPRUS LIBERIA UGANDA CZECHOSLOVAK SOCIALIST LIBYAN ARAB REPUBLIC UKRAINIAN SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLIC LIECHTENSTEIN REPUBLIC DENMARK LUXEMBOURG UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST DOMINICAN REPUBLIC MADAGASCAR REPUBLICS ECUADOR MALAYSIA UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT EGYPT, ARAB REPUBLIC OF MALI BRITAIN AND NORTHERN EL SALVADOR MEXICO IRELAND ETHIOPIA MONACO UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FINLAND MOROCCO URUGUAY FRANCE NETHERLANDS VENEZUELA GABON NEW ZEALAND VIET-NAM GERMANY, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGER YUGOSLAVIA GHANA NIGERIA ZAIRE, REPUBLIC OF GREECE NORWAY ZAMBIA The Agency's Statute was approved on 23 October 1956 by the Conference on the Statute of the IAEA held at United Nations Headquarters, New York; it entered into force on 29 July 1957, The Headquarters of the Agency are situated in Vienna. Its principal objective is "to accelerate and enlarge the contribution of atomic energy to peace, health and prosperity throughout the world". -

Ferricerite-(La) (La, Ce, Ca)9Fe (Sio4)3(Sio3oh)4(OH)3

3+ Ferricerite-(La) (La, Ce, Ca)9Fe (SiO4)3(SiO3OH)4(OH)3 Crystal Data: Hexagonal. Point Group: 3m. Forms boxwork-like aggregates of equant to tabular crystals flattened on [00*1] to 2 mm with dominant rhombohedral and pinacoidal faces, as pseudomorphs after an unidentified hexagonal prismatic mineral. Physical Properties: Cleavage: None. Tenacity: Brittle. Fracture: Conchoidal. Hardness = 5 D(meas.) = 4.7(1) D(calc.) = 4.74 Optical Properties: Translucent. Color: Light yellow to pinkish brown. Streak: White. Luster: Vitreous. Optical Class: Uniaxial (+). ω = 1.810(5) ε = 1.820(5) Cell Data: Space Group: R3c. a = 10.7493(6) c = 38.318(3) Z = 6 X-ray Powder Pattern: Mt. Yuksporr, Khibina massif, Kola Peninsula, Russia. 2.958 (100), 3.47 (40), 3.31(38), 2.833 (37), 2.689 (34), 1.949 (34), 3.53 (26) Chemistry: (1) (2) La2O3 37.57 CaO 5.09 Ce2O3 23.67 Fe2O3 1.40 Pr2O3 0.61 MgO 0.51 Nd2O3 1.48 SiO2 22.38 Sm2O3 0.10 P2O5 0.63 Gd2O3 0.24 H2O 3.20 SrO 1.97 Total 98.85 (1) Mt. Yuksporr, Khibina massif, Kola Peninsula, Russia; average electron microprobe analysis supplemented by IR spectroscopy, H2O by Penfield method; corresponds to (La4.23Ce2.65Ca1.37Sr0.35 Nd0.16Pr0.07Gd0.02Sm0.01)Σ=8.86(Fe0.32Ca0.30Mg0.23)Σ=0.85[SiO4]3[(Si0.84P0.16)Σ=1.00O3(OH)]4(OH)2.78. Mineral Group: Cerite supergroup, cerite group. Occurrence: A late-stage, low-temperature secondary phase in a symmetrically zoned, aegirine- natrolite-microcline vein in gneissose foyaite. -

Zeolites in Tasmania

Mineral Resources Tasmania Tasmanian Geological Survey Record 1997/07 Tasmania Zeolites in Tasmania by R. S. Bottrill and J. L. Everard CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………… 2 USES …………………………………………………………………………………… 2 ECONOMIC SIGNIFICANCE …………………………………………………………… 2 GEOLOGICAL OCCURRENCES ………………………………………………………… 2 TASMANIAN OCCURRENCES ………………………………………………………… 4 Devonian ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Permo-Triassic …………………………………………………………………… 4 Jurassic …………………………………………………………………………… 4 Cretaceous ………………………………………………………………………… 5 Tertiary …………………………………………………………………………… 5 EXPLORATION FOR ZEOLITES IN TASMANIA ………………………………………… 6 RESOURCE POTENTIAL ……………………………………………………………… 6 MINERAL OCCURRENCES …………………………………………………………… 7 Analcime (Analcite) NaAlSi2O6.H2O ……………………………………………… 7 Chabazite (Ca,Na2,K2)Al2Si4O12.6H2O …………………………………………… 7 Clinoptilolite (Ca,Na2,K2)2-3Al5Si13O36.12H2O ……………………………………… 7 Gismondine Ca2Al4Si4O16.9H2O …………………………………………………… 7 Gmelinite (Na2Ca)Al2Si4O12.6H2O7 ……………………………………………… 7 Gonnardite Na2CaAl5Si5O20.6H2O ………………………………………………… 10 Herschelite (Na,Ca,K)Al2Si4O12.6H2O……………………………………………… 10 Heulandite (Ca,Na2,K2)2-3Al5Si13O36.12H2O ……………………………………… 10 Laumontite CaAl2Si4O12.4H2O …………………………………………………… 10 Levyne (Ca2.5,Na)Al6Si12O36.6H2O ………………………………………………… 10 Mesolite Na2Ca2(Al6Si9O30).8H2O ………………………………………………… 10 Mordenite K2.8Na1.5Ca2(Al9Si39O96).29H2O ………………………………………… 10 Natrolite Na2(Al2Si3O10).2H2O …………………………………………………… 10 Phillipsite (Ca,Na,K)3Al3Si5O16.6H2O ……………………………………………… 11 Scolecite CaAl2Si3O10.3H20 ……………………………………………………… -

Minerals Found in Michigan Listed by County

Michigan Minerals Listed by Mineral Name Based on MI DEQ GSD Bulletin 6 “Mineralogy of Michigan” Actinolite, Dickinson, Gogebic, Gratiot, and Anthonyite, Houghton County Marquette counties Anthophyllite, Dickinson, and Marquette counties Aegirinaugite, Marquette County Antigorite, Dickinson, and Marquette counties Aegirine, Marquette County Apatite, Baraga, Dickinson, Houghton, Iron, Albite, Dickinson, Gratiot, Houghton, Keweenaw, Kalkaska, Keweenaw, Marquette, and Monroe and Marquette counties counties Algodonite, Baraga, Houghton, Keweenaw, and Aphrosiderite, Gogebic, Iron, and Marquette Ontonagon counties counties Allanite, Gogebic, Iron, and Marquette counties Apophyllite, Houghton, and Keweenaw counties Almandite, Dickinson, Keweenaw, and Marquette Aragonite, Gogebic, Iron, Jackson, Marquette, and counties Monroe counties Alunite, Iron County Arsenopyrite, Marquette, and Menominee counties Analcite, Houghton, Keweenaw, and Ontonagon counties Atacamite, Houghton, Keweenaw, and Ontonagon counties Anatase, Gratiot, Houghton, Keweenaw, Marquette, and Ontonagon counties Augite, Dickinson, Genesee, Gratiot, Houghton, Iron, Keweenaw, Marquette, and Ontonagon counties Andalusite, Iron, and Marquette counties Awarurite, Marquette County Andesine, Keweenaw County Axinite, Gogebic, and Marquette counties Andradite, Dickinson County Azurite, Dickinson, Keweenaw, Marquette, and Anglesite, Marquette County Ontonagon counties Anhydrite, Bay, Berrien, Gratiot, Houghton, Babingtonite, Keweenaw County Isabella, Kalamazoo, Kent, Keweenaw, Macomb, Manistee,