How to Become a Hindu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhagavad-Gita:Chapters in Sanskrit Bhagavadgita in English

Bhagavad-Gita:Chapters in Sanskrit BGALLCOLOR.pdf (Bhagavadgita in Sanskrit and English in one file) (All 18 chapters in Sanskrit, Transliteration, and Translation.) Bhagavadgita in English BG01 BG02 BG03 BG04 BG05 BG06 BG07 BG08 BG09 BG10 BG11 BG12 BG13 BG14 BG15 BG16 BG17 BG18 HOME PAGE Veeraswamy Krishnaraj http://www.bhagavadgitausa.com/TILAKAM.htm http://www.bhagavadgitausa.com/TILAKAM.pdf You have your Google search engine tailored for this site. Please enter the word(s) in the search box; it will take you to the file with that word in this web site. Enjoy your visit here. Search Search Wikipedia: Go! திலகம் The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 6 [ Page : 115 ] NOTES TAKEN DOWN IN MADRAS, 1892-93 Educate your women first and leave them to themselves; then they will tell you what reforms are necessary for them. In matters concerning them, who are you? Swami Vivekananda 1892-93 Madras/Chennai Tilakam (திலகம்) A mark on the forehead made with colored earths, sandalwood or unguents whether as an ornament or a sectarian distinction; Clerodendrum phlomoides (Vaathamatakki-- வாதமடக்கி a plant- in Tamil; dagdharuha); a freckle compared to a sesamum seed; a kind of skin eruption. Monier Williams Dictionary. It is applied over Ajna Chakra (Bhrumadya = the spot between the eyebrows. Bhru = brow, which is cognate with and derived from Sanskrit Bhru. Ajna Chakra is the sixth Kundalini Chakra on the forehead area, attaining which evokes spiritual knowledge. Ash from the dead bodies was worn in primitive times to remind us about the impermanence of life on earth and the reality and certainty of death. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 Books 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 Translator: Kisari Mohan Ganguli Release Date: March 26, 2005 [EBook #15477] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAHABHARATA VOL 4 *** Produced by John B. Hare. Please notify any corrections to John B. Hare at www.sacred-texts.com The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa BOOK 13 ANUSASANA PARVA Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text by Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] Scanned at sacred-texts.com, 2005. Proofed by John Bruno Hare, January 2005. THE MAHABHARATA ANUSASANA PARVA PART I SECTION I (Anusasanika Parva) OM! HAVING BOWED down unto Narayana, and Nara the foremost of male beings, and unto the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. "'Yudhishthira said, "O grandsire, tranquillity of mind has been said to be subtile and of diverse forms. I have heard all thy discourses, but still tranquillity of mind has not been mine. In this matter, various means of quieting the mind have been related (by thee), O sire, but how can peace of mind be secured from only a knowledge of the different kinds of tranquillity, when I myself have been the instrument of bringing about all this? Beholding thy body covered with arrows and festering with bad sores, I fail to find, O hero, any peace of mind, at the thought of the evils I have wrought. -

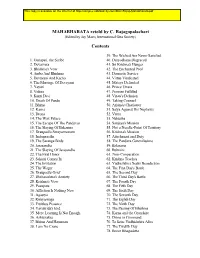

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

DR.RUPNATHJI( DR.RUPAK NATH ) Hindi, the Official Language of India, Is Developed from Shauraseni Apabhransha

ABOUT SANSKRIT By Dr.rupnathji(Dr.Rupak Nath) . Evolution of Sanskrit Language Sanskrit is an ancient and classical language of India in which ever first book of the world Rigveda was compiled. The Vedas are dated by different scholars from 6500 B.C. to 1500 B.C. Sanskrit language must have evolved to its expressive capability prior to that. It is presumed that the language used in Vedas was prevalent in the form of different dialects. It was to some extent different from the present Sanskrit. It is termed as Vedic Sanskrit. Each Veda had its book of grammar known as Pratishakhya. The Pratishakhyas explained the forms of the words and other grammatical points. Later, so many schools of grammar developed. During this period a vast literature -Vedas, Brahmana-Granthas, Aranyakas, Upanishads and Vedangas had come to existence which could be termed as Vedic Literature being written in Vedic Sanskrit. Panini (500 B.C.) was a great landmark in the development of Sanskrit language. He, concising about ten grammar schools prevalent during his time, wrote the master book of grammar named Ashtadhyayi which served as beacon for the later period. Literary Sanskrit and spoken Sanskrit both followed Panini’s system of language. Today the correctness of SanskritDR.RUPNATHJI( language is DR.RUPAKtested upon NATH the )touchstone of Panini’s Ashtadhyayee. Sanskrit is said to belong to Indo – Aryan or Indo Germanic family of languages which includes Greek, Latin and other alike languages. William Jones, who was already familiar with Greek and Latin, when came in contact with Sanskrit, remarked that Sanskrit is more perfect than Greek, more copious than Latin and more refined than either. -

Poetry's Afterthought: Kalidasa and the Experience of Reading Shiv

Poetry’s Afterthought: Kalidasa and the Experience of Reading Shiv Subramaniam Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy on the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Shiv Subramaniam All rights reserved ABSTRACT Poetry’s Afterthought: Kalidasa and the Experience of Reading Shiv Subramaniam This dissertation concerns the reception of the poet Kalidasa (c. 4th century), one of the central figures in the Sanskrit literary tradition. Since the time he lived and wrote, Kalidasa’s works have provoked many responses of different kinds. I shall examine how three writers contributed to this vast tradition of reception: Kuntaka, a tenth-century rhetorician from Kashmir; Vedantadesika, a South Indian theologian who lived in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries; and Sri Aurobindo, an Indian English writer of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who started out as an anticolonial activist and later devoted his life to spiritual exercises. While these readers lived well after Kalidasa, they were all deeply invested in his poetry. I wish to understand why Kalidasa’s poetry continued to provoke extended responses in writing long after its composition. It is true that readers often use past literary texts to various ends of their own devising, just as they often fall victim to reading texts anachronistically. In contradistinction to such cases, the examples of reading I examine highlight the role that texts themselves, not just their charisma or the mental habits of their readers, can have in constituting the reading process. They therefore urge us to formulate a more robust understanding of textual reception, and to reconsider the contemporary practice of literary criticism. -

The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism the Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism

The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism James G. Lochtefeld, Ph.D. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. New York Published in 2001 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010 Copyright © 2001 by James G. Lochtefeld First Edition All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lochtefeld, James G., 1957– The illustrated encyclopedia of Hinduism/James G. Lochtefeld. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8239-2287-1 (set) ISBN 0-8239-3180-3 (volume 2) 1. Hinduism Encyclopedias. I. Title BL1105.L63 2000 294.5'03—dc21 99-27747 CIP Manufactured in the United States of America Nachiketas poetry are dedicated to Krishna, a dif- ferent form of Vishnu. This seeming divergence may reflect her conviction that all manifestations of Vishnu are ultimately the same or indicate the dif- N ference between personal devotion and literary expression. The thirty poems in the Nacciyar Tirumoli are told by a group of unmar- ried girls, who have taken a vow to bathe Nabhadas in the river at dawn during the coldest (c. 1600) Author of the Bhaktamal month of the year. This vow has a long (“Garland of Devotees”). In this hagio- history in southern India, where young graphic text, he gives short (six line) girls would take the oath to gain a good accounts of the lives of more than two husband and a happy married life. -

Just Drop It - Part 1

Just Drop It - Part 1 Date: 2011-07-12 Author: Vaijayantimala devi dasi Hare Krishna Prabhujis and Matajis, Please accept my humble pranams! All glories to Srila Prabhupada and Srila Gurudev! The following is the transcription of the wonderful class by our beloved God brother HG Devakinandan prabhuji on 28- 04-2011 in Abu Dhabi on Aila Gita. Maharaj actually touched on Aila gita for two to three weeks. Maharaj did very intense study and spoke very intensely on this particular episode in Srimad Bhagavatam known as Ailagita and it speaks about the story of King Pururavas and Urvashi. When Maharaj was recovering from his stroke in London, for one month, he spent time studying third canto, ninthchapter which is Brahma’s prayers for creative energy and then he spent a lot of time on Aila gita. This Aila gita appears in the 11th canto 19th chapter. But it has its beginnings inthe ninth canto and then it continues in the 11th canto. So it is a wonderful story - wonderful episode and it means so much because Maharaj studied this and revealed so much. Solet us try reading couple of verses from it. SB 11.26.19-20: pitroḥ kiṁ svaṁ nu bhāryāyāḥ svāmino ’gneḥ śva-gṛdhrayoḥ kim ātmanaḥ kiṁ suhṛdām iti yo nāvasīyate tasmin kalevare ’medhye tuccha-niṣṭhe viṣajjate aho su-bhadraṁ su-nasaṁ su-smitaṁ ca mukhaṁ striyaḥ One can never decide whose property the body actually is. Does it belong to one's parents, who have given birth to it, to one's wife, who gives it pleasure, or to one's employer, who orders the body around? Is it the property of the funeral fire or of the dogs and jackals who may ultimately devour it? Is it the property of the indwelling soul, who partakes in its happiness and distress, or does the body belong to intimate friends who encourage and help it? Although a man never definitely ascertains the proprietor of the body, he becomes most attached to it. -

Hinduism) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

אידה ایدا https://fa.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%AF%D8%A7_%28%D9%81%DB%8C%D9% 84%D9%85_%DB%B2%DB%B0%DB%B1%DB%B3%29 إیدا इडा ا ڈ ا http://uh.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx इडा ਇਡਾ http://uh.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx اڈا فرشتہ ਇਡਾ ਫ਼ਰਿਸ਼ਤਾ http://g2s.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx Idā in the Rigveda, literally means signifies food and refreshment, personified as the goddess of speech. Idā is also associated with Sarasvati, the goddess of knowledge. http://www.pitarau.com/nd/All/ida Ida … (Sanskrit इडा) A deep, significant word in Hindu esotericism. Literally, "speech, food, praise, particular artery on the left side of the body, animation, stream or flow of praise and worship, goddess iDA or iLA, commendation, recreation, comfort, tubular vessel, heaven, refreshing draught, cow, vital spirit, libation, refreshment, earth, offering, at this moment." The word ida is especially utilized to indicate the feminine serpent of our internal energetic bipolarity, which is symbolized on the Caduceus of Mercury, and in the bible by Eve, the olive trees, and the Two Witnesses. Ida is related to procreation. http://gnosticteachings.org/glossary/i.html Ila (Hinduism) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ila_(Hinduism) Ila (Hinduism) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Ila is an androgyne in Hindu mythology, known for his/her sex changes. As a man, he is known as Ila (Sanskrit: इल ) or Ila/Il ā Sudyumna and as a woman, is called Il ā (Sanskrit: इला ). Il ā is considered the chief progenitor of the Lunar Dynasty (Chandravamsha or Somavamsha) of Indian kings - also known as the Ailas ("descendants of Il ā"). -

Signature Redacted Signature of Author: Program in Comparative Media Studies 12 May 2009

Indian Comics as Public Culture MASSACHUSETS INSTITUTE By OF TECHNOLOGY Abhimnanyu Das JL0821 B.A. English, Franklin and Marshall College 2005 SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2009 0 2009 Abhimanyu Das. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Signature of Author: Program in Comparative Media Studies 12 May 2009 Certified by: Signature redacted_ _ _ Henry Jenkins III 67 et d'Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of C dufiarative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Signature redacted Accepted by:_________________ William Charles Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-director, Comparative Media Studies I 2 Indian Comics as Public Culture by Abhimanyu Das Submitted to the Program in Comparative Media Studies on May 12 2009, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT: The Amar Chitra Katha (ACK) series of comic books have, since 1967, dominated the market for domestic comic books in India. In this thesis, I examine how these comics function as public culture, creating a platform around which groups and individuals negotiate and re-negotiate their identities (religious, class, gender, regional, national) through their experience of the mass-media phenomenon of ACK. I also argue that the comics, for the most part, toe a conservative line - drawing heavily from Hindu nationalist schools of thought. -

Year III-Chap.3-MAHABHARATA

CHAPTER THREE Pandavas in MAHABHARATA Year III Chapter 3-MAHABHARATA CHANDRA VAMSA The first king of the race of the Moon was PURURAVAS His great grandson l KING YAYATI His sons l l l KING PURU KING YADU One of his descendants His descendants were called Yadavas l l KING DUSHYANT LORD KRISHNA His son l KING BHARATA – one of his descendants l KING KURU One of his descendants l KING SHANTANU His sons l l l l CHITRANGAD VICHITRAVIRYA BHEESHMA His sons l l l DHRITARASHTRA PANDU His 100 sons called after King Kuru as His five sons called after him as l l KAURAVAS PANDAVAS l Arjuna’s grandson KING PARIKSHIT 44 Year III Chapter 3-MAHABHARATA MAHABHARATA Mahabharata is the longest epic poem in the world, originally written in Sanskrit, the ancient language of India. It was composed by Sage Veda Vyasa several thousand years ago. Vyasa dictated the entire epic at a stretch while Lord Ganesha wrote it down for him. The epic has been divided into the following: o ADI PARVA o SABHA PARVA o VANA PARVA o VIRATA PARVA o UDYOGA PARVA o BHEESHMA PARVA o DRONA PARVA o KARNA PARVA o SALYA PARVA / AFTER THE WAR ADI PARVA The story of Mahabharata starts with King Dushyant, a powerful ruler of ancient India. Dushyanta married Shakuntala, the foster-daughter of sage Kanva. Shakuntala was born to Menaka, an apsara (nymph) of Indra's court, and sage Vishwamitra. Shakuntala gave birth to a worthy son Bharata, who grew up to be fearless and strong. It was after his name India came to be known as Bharatavarsha. -

Brahma's Hair

BRAHMA'S HAIR ON THE MYTHOLOGY OF INDIAN PLANTS Maneka Gandhi Yasmin Singh 1 CORAL JASMINE Latin Name : Nyctanthes arbortristis English Names : Queen of the Night, Coral Jasmine Indian Names : Bengali: Shephalika, Siuli Hindi: Harashringara Marathi: Parijata, Kharsati Sanskrit: Parijata Tamil: Parijata, Paghala Family : Oleaceae Nyctanthes means Night Flower and arbortristis the Sad Tree. Parijata, the Sanskrit name, means descended from the sea. Harashringara is ornament of the gods or beautiful ornament. The flowers are gathered for religious offerings and to make garlands. The orange heart is used for dyeing silk and cotton, a practice that started with Buddhist monks whose orange robes were given their colour by this flower. The Parijata is regarded in Hindu mythology as one of the five wish-granting trees of Devaloka. Why the Parijata blooms at night A legend in the Vishnu Purana tells of a king who had a beautiful and sensitive daughter called Parijata. She fell in love with Surya, the sun. Leave your kingdom and be mine, said the sun passionately. Obediently Parijata shed her royal robes and followed her beloved. But the sun grew cold as he tired of Parijata and soon he deserted her and fled back to the sky. The young princess died heartbroken. She was burnt on the funeral pyre and from her ashes grew a single tree. From its drooping branches grew the most beautiful flowers with deep orange hearts. But. since the flowers cannot bear the sight of the sun, they only bloom when it disappears from the sky and, as its first rays shoot out at dawn, the flowers fall to the ground and die. -

Purumitra Ii 620 Pururavas I

PURUMITRA II 620 PURURAVAS I PURUMITRA. II. The first Mandala oftheRgveda born Candra took it away and named it Budha. Brahma mentions a Rajarsi youth Vimada marrying the daughter and other rsis gave Budha a seat among the planets. of Purumitra. Budha married Ila and they got a son named Pururavas. PURUNlTHA. See under Parunltha. ^See under Ila). After that Budha performed a hundred PURURAVAS. I. A of Candravarh a prominent king Asvamedhayagas. He then enjoyed world prosperity (lunar race). as lord of Saptadvlpa living in the beautiful Himadri- |} Candravamsa and birth Pururavas. Descend- Origin of of srnga. worshipping Brahma. (Chapter 12, Bhaga 3, in order from Brahma came Atri Candra Budha ing Padma Purana). Pururavas. The dynasty which came from Candra was Pururavas and the curse. Pururavas his bril- called the Candravarhxa. Though Budha was the first 2) Testing by liance a hundred and lived king of CandravarhSa it was Pururavas who became performed Asvamedhayagas in at Great demons like Kesi celebrated. The story of the birth of Pururavas is given glory Himadrisrnga. became his servants. Urvasi attracted his below : by beauty became his wife. While he was like that Brahma in the beginning deputed the sage Atri for the living Dharma, Artha and Kama went in to his to test work of creation. Atrimaharsi started the penance disguise palace him. He received them all well but more attention to called anuttara to acquire sufficient power for creation. paid Dharma. Artha and Kama and cursed him. After some years Saccidananda brahma with an aura of got angry Artha cursed him that he would be ruined lustre reflected in the heart of that pure and serene saying by his and Kama cursed him he would soul.