Wisconsin's Ecological Features and Opportunities for Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flambeau Flowage Watershed Wisconsin Watersheds

Wisconsin Flambeau Flowage Watersheds Watershed 2014 Water Quality Management Plan Update Upper Chippewa Basin, Wisconsin May 2015 Th e Flambeau Flowage Watershed is located primarily in Iron County with smaller sections in northwest Vilas County and northern Price County. It has an area of 247 square miles. Th e Turtle-Flambeau Flowage is the largest water- body at 12,942 acres. Th ere are numerous other lakes. Th e Turtle River passes through many of the lakes and is the largest stream. Th e lower end of the Manitowish River is also present. Th e watershed is minimally developed, with 99% of its area consisting of forest, wetland, and open Contents water. Watershed Details . 1 Population and Land Use . 1 Hydrology . 2 Ecological Landscapes . 2 Map 1: Flambeau Flowage Watershed Historical Note . 3 Watershed Condition . 3 Watershed Details Overall Condition . 3 River and Stream Condition . 3 Population and Land Use Lake Health . 5 Wetland Health . 5 Groundwater . 6 Table 1: Flambeau Flowage Watershed Land Use Flambeau Flowage Watershed Point and Nonpoint Pollution . 7 Waters of Note . 8 Percent of (UC14) Land Use Percentages Land Use Acres Trout Waters . 8 Area 0.5% Outstanding & Exceptional Resource Forest 74,158.45 46.88% Forest 19% Waters . 8 Wetland 52,456.72 33.16% Impaired Waters. 9 Open Water & Wetland Fish Consumption . 9 Open Space 30,232.58 19.11% 47% Aquatic Invasive Species . 10 Agriculture 788.61 0.50% Ope n Wate r & Species of Special Concern . 10 Grassland 265.09 0.17% Open Space State Natural and Wildlife Areas . 10 Suburban 252.42 0.16% Urban 43.59 0.03% 33% Agriculture Watershed Actions . -

Ground-Water Conditions in the Milwaukee-Waukesha Area, Wisconsin

Ground-Water Conditions in the Milwaukee-Waukesha Area, Wisconsin GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1229 Ground-Water Conditions in the Milwaukee -Waukesha Area, Wisconsin By F. C. FOLEY, W. C. WALTON, and W. J. DRESCHER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1229 A progress report, with emphasis on the artesian sandstone aquifer. Prepared in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1953 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director f For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 70 cents CONTENTS Page Abstract.............................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction........................................................................................................................ 3 Purpose and scope of report.................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments...................................................................................................... 5 Description of the area............................................................................................ 6 Previous reports........................................................................................................ 6 Well-numbering system.............................................................................................. 7 Stratigraphy....................................................................................................................... -

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

2. Blue Hills 2001

Figure 1. Major landscape regions and extent of glaciation in Wisconsin. The most recent ice sheet, the Laurentide, was centered in northern Canada and stretched eastward to the Atlantic Ocean, north to the Arctic Ocean, west to Montana, and southward into the upper Midwest. Six lobes of the Laurentide Ice Sheet entered Wisconsin. Scale 1:500,000 10 0 10 20 30 PERHAPS IT TAKES A PRACTICED EYE to appreciate the landscapes of Wisconsin. To some, MILES Wisconsin landscapes lack drama—there are no skyscraping mountains, no monu- 10 0 10 20 30 40 50 mental canyons. But to others, drama lies in the more subtle beauty of prairie and KILOMETERS savanna, of rocky hillsides and rolling agricultural fi elds, of hillocks and hollows. Wisconsin Transverse Mercator Projection The origin of these contrasting landscapes can be traced back to their geologic heritage. North American Datum 1983, 1991 adjustment Wisconsin can be divided into three major regions on the basis of this heritage (fi g. 1). The fi rst region, the Driftless Area, appears never to have been overrun by glaciers and 2001 represents one of the most rugged landscapes in the state. This region, in southwestern Wisconsin, contains a well developed drainage network of stream valleys and ridges that form branching, tree-like patterns on the map. A second region— the northern and eastern parts of the state—was most recently glaciated by lobes of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which reached its maximum extent about 20,000 years ago. Myriad hills, ridges, plains, and lakes characterize this region. A third region includes the central to western and south-central parts of the state that were glaciated during advances of earlier ice sheets. -

The Geography Fox-Winnebago Valley

WISCONSIN GEOLOGICAL AND NATURAL HISTORY SURVEY E. A. BIRGE, Director W. O. HOTCHKISS, State Geologist Bulletin XU! Educational Series No. 5 THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE FOX-WINNEBAGO VALLEY BY RAY HUGHES WHITBECK Pro/ellor 0/ PhYliography and Geographu Uniuuluu 0/ Wilconsin ivm MADISON, WIS. PuBLISHED BY THE STATE 1915 "scolaln 68010glcal and Natural History Surve, BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS EMANUEL L. PHILIPP Governor of the State. CHARLES R. VAN HISE, Pusident. President of the University of Wisconsin. CHARLES P. CARY, Vice-President State Superintendent of Public Instruction. JABE ALFORD President of the Commis&ioners of Fisheries HENRY L. WARD, Secretary President of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters. STAFF OF THE SURVEY ADMINISTRATION: EDWARD A. BIRGE, Director and Superintendent In immediate charge of Natural History Division. WILLIAM O. HOTCHKISS, State Geologist. In immediate charge of Geology Division. LILLIAN M. VEERHUSEN, Clerk. GEOLOGY DIVISION: WILLIAM O. HOTCHKISS, In charge. T. C. CHAMBERLIN, Consulting Geologist, Pleistocene Geology. SAMUEL WEIDMAN, Geologist, Areal Geology. E. F. BEAN, Geologist, Chief of Field Parties. O. W. WHEELWRIGHT, Geologist, Chief of Field Parties. R. H. WHITBECK, Geologist, Geography of Lower Fox Valley. LAWRENCE MARTIN, Geologist, Physical Geography. E. STEIDTMANN, Geologist, Limestones. F. E. WILLIAMS, Geologist, Geography and History. NATURAL HISTORY DIVISION: EDWARD A. BIRGE, In charge. CHANCEY JUDAY, Lake Survey. H. A. SCHUETTE, Chemist. DIVISION OF SOILS: A. R. WHITSON, In charge. W. J. GEIB,* Inspector and Editor. GUY CONREY, Analyst. T. J. DUNNEWALD, Field Assistant and Analyst. CARL THOMPSON, Field Assistant and Analyst. C. B. POST, Field Assistant and Analyst. W. C. BOARDMAN, Field Assistant and Analyst. -

The Tamarack Bogs of the Driitless Area of Wisconsin

BULLETIN OF THE PUBLIC MUSEUM OF THE CITY OF MILWAUKEE Vol. 7, No. 2, Pp. 231,304, Plate, 39-44, Text Figure• 1,3 Maps 1,27, June 9, 1933 THE TAMARACK BOGS OF THE DRIITLESS AREA OF WISCONSIN By Henry P. Hansen MILWAUKEE, WIS., U. S. A. Published by Order of the Board of Trustee, BULLETIN OF THE PUBLIC MUSEUM OF THE CITY OF MILWAUKEE Vol. 7, No. 2, Pp. 231,304, Plates 39-44, Text Figures 1·3 Maps 1-27, June 9, 1933 THE TAMARACK BOGS OF THE DRIFTLESS AREA OF WISCONSIN By Henry P. Hansen MILWAUKEE, WIS., U.S. A. Publi1hcd by Order of the Board of Trmtec• Prinled by the CA..~NON PRINTING CO. :Milwaukee, Wis. Engravings by the SCHROEDER ENGRAVING CO. Milwaukee, Wis. THE TAMARACK BOGS OF THE DRIFTLESS AREA* OF WISCONSIN CONTENTS Page Introduction 237 Glaciation in Wisconsin. 237 Topography and Geological fom1ations in the Driftless Area .. 241 Characteristics and Development of Bogs in the Glaciated Region ................ ............................ 241 Glaciation in relation to the Present Distribution of North American Bogs . 244 Physiographic Features of the Sites of the Bogs in the Driftless Area ......... ........................................ 246 Method of Origin of Bogs in the Driftless Area ........... .... 250 Existence of Bog Plants on Sandstone Bluffs in the Driftless Area. 253 Tamarack Creek Bog. 256 Little Tamarack Creek Bog ..... .......... ..... ........ 259 Hub City Bog ............................................. 259 Se.xtonville Bog . 260 Bogs in the Valley of the La Crosse River, La Crosse County .... 262 Mormon Coulee Bog. La Crosse County ...................... 264 Past Existence of Bog Plants in the Driftless Area .............. 266 *The work upon which this pa~r is ba~ed was done in the laboratory 0£ the l'nivcr-.ity of Wisconsin under the supen•ision of Or. -

Wisconsin's John Muir

Wisconsin’s John Muir An Exhibit Celebrating the Centennial of the National Park Service “Oh, that glorious Wisconsin wilderness! “Everything new and pure in the very prime of the spring when Nature’s pulses were beating highest and mysteriously keeping time with our own!” “Wilderness is a necessity... Mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life.” This exhibit was made possible through generous support from the estate of John Peters and the Follett Charitable Trust Muir in Wisconsin “When we first saw Fountain Lake Meadow, on a sultry evening, sprinkled with millions of lightning- bugs throbbing with light, the effect was so strange and beautiful that it seemed far too marvelous to be real.” John Muir (1838–1914) was one of America’s most important environmental thinkers and activists. He came to Wisconsin as a boy, grew up near Portage, and attended the University of Wisconsin. After decades of wandering in the mountains of California, he led the movement for national parks and helped create the Sierra Club. But for much of his life, Muir’s call to protect wild places fell on deaf ears. Muir studied science in Madison but quit in 1863 without a degree, “...leaving one University for another, the Wisconsin University for the University of the Wilderness.” Muir’s letter to the classmate who taught him botany at UW The Movement for National Parks Yosemite Valley “Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in, where Nature may heal and cheer and give strength to body and soul alike.” In 1872, Congress named Yellowstone the first national park. -

Fishing Regulations, 2020-2021, Available Online, from Your License Distributor, Or Any DNR Service Center

Wisconsin Fishing.. it's fun and easy! To use this pamphlet, follow these 5 easy steps: Restrictions: Be familiar with What's New on page 4 and the License Requirements 1 and Statewide Fishing Restrictions on pages 8-11. Trout fishing: If you plan to fish for trout, please see the separate inland trout 2 regulations booklet, Guide to Wisconsin Trout Fishing Regulations, 2020-2021, available online, from your license distributor, or any DNR Service Center. Special regulations: Check for special regulations on the water you will be fishing 3 in the section entitled Special Regulations-Listed by County beginning on page 28. Great Lakes, Winnebago System Waters, and Boundary Waters: If you are 4 planning to fish on the Great Lakes, their tributaries, Winnebago System waters or waters bordering other states, check the appropriate tables on pages 64–76. Statewide rules: If the water you will be fishing is not found in theSpecial Regulations- 5 Listed by County and is not a Great Lake, Winnebago system, or boundary water, statewide rules apply. See the regulation table for General Inland Waters on pages 62–63 for seasons, length and bag limits, listed by species. ** This pamphlet is an interpretive summary of Wisconsin’s fishing laws and regulations. For complete fishing laws and regulations, including those that are implemented after the publica- tion of this pamphlet, consult the Wisconsin State Statutes Chapter 29 or the Administrative Code of the Department of Natural Resources. Consult the legislative website - http://docs. legis.wi.gov - for more information. For the most up-to-date version of this pamphlet, go to dnr.wi.gov search words, “fishing regulations. -

Northwest Lowlands Ecological Landscape

Chapter 16 Northwest Lowlands Ecological Landscape Where to Find the Publication The Ecological Landscapes of Wisconsin publication is available online, in CD format, and in limited quantities as a hard copy. Individual chapters are available for download in PDF format through the Wisconsin DNR website (http://dnr.wi.gov/, keyword “landscapes”). The introductory chapters (Part 1) and supporting materials (Part 3) should be downloaded along with individual ecological landscape chapters in Part 2 to aid in understanding and using the ecological landscape chapters. In addition to containing the full chapter of each ecological landscape, the website highlights key information such as the ecological landscape at a glance, Species of Greatest Conservation Need, natural community management opportunities, general management opportunities, and ecological landscape and Landtype Association maps (Appendix K of each ecological landscape chapter). These web pages are meant to be dynamic and were designed to work in close association with materials from the Wisconsin Wildlife Action Plan as well as with information on Wisconsin’s natural communities from the Wisconsin Natural Heritage Inventory Program. If you have a need for a CD or paper copy of this book, you may request one from Dreux Watermolen, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, P.O. Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707. Photos (L to R): Red-shouldered Hawk, photo © Laurie Smaglick Johnson; arctic fritillary, photo by Ann Thering; Sedge Wren, photo © Laurie Smaglick Johnson; gray wolf, photo by Gary Cramer, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Golden-winged Warbler, photo © Laurie Smaglick Johnson. Suggested Citation Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 2015. The ecological landscapes of Wisconsin: An assessment of ecological resources and a guide to planning sustainable management. -

Wisconsin's Wetland Gems

100 WISCONSIN WETLAND GEMS ® Southeast Coastal Region NE-10 Peshtigo River Delta o r SC-1 Chiwaukee Prairie NE-11 Point Beach & Dunes e i SC-2 Des Plaines River NE-12 Rushes Lake MINNESOTA k e r a p Floodplain & Marshes NE-13 Shivering Sands & L u SC-3 Germantown Swamp Connected Wetlands S SC-4 Renak-Polak Woods NE-14 West Shore Green Bay SU-6 SU-9 SC-5 Root River Riverine Forest Wetlands SU-8 SU-11 SC-6 Warnimont Bluff Fens NE-15 Wolf River Bottoms SU-1 SU-12 SU-3 SU-7 Southeast Region North Central Region SU-10 SE-1 Beulah Bog NC-1 Atkins Lake & Hiles Swamp SU-5 NW-4 SU-4 SE-2 Cedarburg Bog NC-2 Bear Lake Sedge Meadow NW-2 NW-8 MICHIGAN SE-3 Cherokee Marsh NC-3 Bogus Swamp NW-1 NW-5 SU-2 SE-4 Horicon Marsh NC-4 Flambeau River State Forest NW-7 SE-5 Huiras Lake NC-11 NC-12 NC-5 Grandma Lake NC-9 SE-6 Lulu Lake NC-6 Hunting River Alders NW-10 NC-13 SE-7 Milwaukee River NC-7 Jump-Mondeaux NC-8 Floodplain Forest River Floodplain NW-6 NC-10 SE-8 Nichols Creek NC-8 Kissick Alkaline Bog NW-3 NC-5 NW-9 SE-9 Rush Lake NC-9 Rice Creek NC-4 NC-1 SE-10 Scuppernong River Area NC-10 Savage-Robago Lakes NC-2 NE-7 SE-11 Spruce Lake Bog NC-11 Spider Lake SE-12 Sugar River NC-12 Toy Lake Swamp NC-6 NC-7 Floodplain Forest NC-13 Turtle-Flambeau- NC-3 NE-6 SE-13 Waubesa Wetlands Manitowish Peatlands W-7 NE-9 WISCONSIN’S WETLAND GEMS SE-14 White River Marsh NE-2 Northwest Region NE-8 Central Region NE-10 NE-4 NW-1 Belden Swamp W-5 NE-12 WH-5 Mink River Estuary—Clint Farlinger C-1 Bass Lake Fen & Lunch NW-2 Black Lake Bog NE-13 NE-14 ® Creek Sedge Meadow NW-3 Blomberg Lake C-4 WHAT ARE WETLAND GEMS ? C-2 Bear Bluff Bog NW-4 Blueberry Swamp WH-2WH-7 C-6 NE-15 NE-1 Wetland Gems® are high quality habitats that represent the wetland riches—marshes, swamps, bogs, fens and more— C-3 Black River NW-5 Brule Glacial Spillway W-1 WH-2 that historically made up nearly a quarter of Wisconsin’s landscape. -

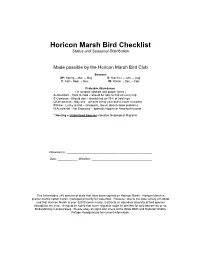

Horicon Marsh Bird Checklist Status and Seasonal Distribution

Horicon Marsh Bird Checklist Status and Seasonal Distribution Made possible by the Horicon Marsh Bird Club Seasons SP: Spring – Mar. – May S: Summer – June – Aug. F: Fall – Sept. – Nov. W: Winter – Dec. – Feb. Probable Abundance ( in suitable habitats and proper times ) A Abundant - Hard to miss – should be able to find on every trip C Common - Should see – should find on 75% of field trips U Uncommon - May see – present every year but in lesser numbers R Rare - Lucky to find – infrequent, few or identification problems H Accidental - Not Expected – sporadic reports or historical records * Nesting – Underlined Species indicates Neotropical Migrants Observer(s): ____________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Weather: _____________________________________ This list includes 288 species of birds that have been sighted on Horicon Marsh. Horicon Marsh is predominantly cattail marsh, managed primarily for waterfowl. However, due to the wide variety of habitat and that Horicon Marsh is over 32000 acres in size, it attracts an abundant diversity of bird species throughout the year. It should be noted that some migrants might be present for only two weeks or so. Birdwatching is encouraged. Please obey all signs and check at the State DNR and National Wildlife Refuge Headquarters for current information. Sp S F W Loons __ Common Loon R R H Grebes __ Pied-billed Grebe* CCCR __ Horned Grebe R R __ Red-necked Grebe* R R R __ Eared Grebe R R R Pelicans __ American White Pelican* C C C Cormorants __ Double-crested Cormorant* C C C R Bitterns, Herons __ American Bittern* UUUR __ Least Bittern* U U U __ Great Blue Heron* AAAR __ Great Egret* C C C __ Snowy Egret R R R __ Little Blue Heron R R R __ Cattle Egret R R R __ Green Heron* U U U __ Black-crowned Night-Heron* CCCR American Vultures __ Turkey Vulture* U U R Swans, Geese and Ducks __ Gr. -

2009 STATE PARKS GUIDE.Qxd

VISITOR INFORMATION GUIDE FOR STATE PARKS, FORESTS, RECREATION AREAS & TRAILS Welcome to the Wisconsin State Park System! As Governor, I am proud to welcome you to enjoy one of Wisconsin’s most cherished resources – our state parks. Wisconsin is blessed with a wealth of great natural beauty. It is a legacy we hold dear, and a call for stewardship we take very seriously. WelcomeWelcome In caring for this land, we follow in the footsteps of some of nation’s greatest environmentalists; leaders like Aldo Leopold and Gaylord Nelson – original thinkers with a unique connection to this very special place. For more than a century, the Wisconsin State Park System has preserved our state’s natural treasures. We have balanced public access with resource conservation and created a state park system that today stands as one of the finest in the nation. We’re proud of our state parks and trails, and the many possibilities they offer families who want to camp, hike, swim or simply relax in Wisconsin’s great outdoors. Each year more than 14 million people visit one of our state park properties. With 99 locations statewide, fun and inspiration are always close at hand. I invite you to enjoy our great parks – and join us in caring for the land. Sincerely, Jim Doyle Governor Front cover photo: Devil’s Lake State Park, by RJ & Linda Miller. Inside spread photo: Governor Dodge State Park, by RJ & Linda Miller. 3 Fees, Reservations & General Information Campers on first-come, first-served sites must Interpretive Programs Admission Stickers occupy the site the first night and any Many Wisconsin state parks have nature centers A vehicle admission sticker is required on consecutive nights for which they have with exhibits on the natural and cultural history all motor vehicles stopping in state park registered.