Wisconsin's Door Peninsula and Its Geomorphology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lake Michigan Natural Division Characteristics

The Lake Michigan Natural Division Characteristics Lake Michigan is a dynamic deepwater oligotrophic ecosystem that supports a diverse mix of native and non-native species. Although the watershed, wetlands, and tributaries that drain into the open waters are comprised of a wide variety of habitat types critical to supporting its diverse biological community this section will focus on the open water component of this system. Watershed, wetland, and tributaries issues will be addressed in the Northeastern Morainal Natural Division section. Species diversity, as well as their abundance and distribution, are influenced by a combination of biotic and abiotic factors that define a variety of open water habitat types. Key abiotic factors are depth, temperature, currents, and substrate. Biotic activities, such as increased water clarity associated with zebra mussel filtering activity, also are critical components. Nearshore areas support a diverse fish fauna in which yellow perch, rockbass and smallmouth bass are the more commonly found species in Illinois waters. Largemouth bass, rockbass, and yellow perch are commonly found within boat harbors. A predator-prey complex consisting of five salmonid species and primarily alewives populate the pelagic zone while bloater chubs, sculpin species, and burbot populate the deepwater benthic zone. Challenges Invasive species, substrate loss, and changes in current flow patterns are factors that affect open water habitat. Construction of revetments, groins, and landfills has significantly altered the Illinois shoreline resulting in an immeasurable loss of spawning and nursery habitat. Sea lampreys and alewives were significant factors leading to the demise of lake trout and other native species by the early 1960s. -

Phase I Avian Risk Assessment

PHASE I AVIAN RISK ASSESSMENT Garden Peninsula Wind Energy Project Delta County, Michigan Report Prepared for: Heritage Sustainable Energy October 2007 Report Prepared by: Paul Kerlinger, Ph.D. John Guarnaccia Curry & Kerlinger, L.L.C. P.O. Box 453 Cape May Point, NJ 08212 (609) 884-2842, fax 884-4569 [email protected] [email protected] Garden Peninsula Wind Energy Project, Delta County, MI Phase I Avian Risk Assessment Garden Peninsula Wind Energy Project Delta County, Michigan Executive Summary Heritage Sustainable Energy is proposing a utility-scale wind-power project of moderate size for the Garden Peninsula on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan in Delta County. This peninsula separates northern Lake Michigan from Big Bay de Noc. The number of wind turbines is as yet undetermined, but a leasehold map provided to Curry & Kerlinger indicates that turbines would be constructed on private lands (i.e., not in the Lake Superior State Forest) in mainly agricultural areas on the western side of the peninsula, and possibly on Little Summer Island. For the purpose of analysis, we are assuming wind turbines with a nameplate capacity of 2.0 MW. The turbine towers would likely be about 78.0 meters (256 feet) tall and have rotors of about 39.0 m (128 feet) long. With the rotor tip in the 12 o’clock position, the wind turbines would reach a maximum height of about 118.0 m (387 feet) above ground level (AGL). When in the 6 o’clock position, rotor tips would be about 38.0 m (125 feet) AGL. However, larger turbines with nameplate capacities (up to 2.5 MW and more) reaching to 152.5 m (500 feet) are may be used. -

Living on the Edge

Living on the Ledge Life in Eastern Wisconsin Outline • Location of Niagara Escarpment Eastern U.S. • General geology • Locations of the escarpment in Wisconsin • Neda Iron mine and early geologists • Silurian Dolostone of Waukesha Co.- Lannon Stone , past and present quarries • The Great Lakes Watershed Niagara Falls NY – Rock falls caused by undercutting: notice the pile of broken rock at base of American falls. Top Layer is equivalent to Waukesha/ Lannon Stone You may have see Niagara Falls locally if you visited the Hudson River painters exhibit at MAM. Fredrick Church 1867 Fredrick Church 1857 Or you can see a bit of the Ledge as a table top while meditating with a bottle of Silurian Stout in my yard Fr. Louis Hennepin sketch of Niagara Falls 1698 Niagara Falls - the equivalent stratigraphic section in N.Y. from which the correlation of the Neda to the Clinton Iron was incorrectly made Waterfalls associated with the Niagara Escarpment all follow this pattern- resistant cap rock and soft shale underneath The “Ledge” of Western NY The Niagara Escarpment Erie Canal locks at Lockport NY The Erie Canal that followed the lowland until it reached the Niagara Escarpment The names of Silurian rocks in the Midwestern states change with location and sometimes with authors! 417mya Stratigraphic column for rocks of Eastern Wisconsin. 443mya Note the Niagara Escarpment rocks at the top. The Escarpment is the result of resistant dolostone 495mya cap rock and soft shale rock below The Michigan Basin- Showing outcrops of Silurian rocks Location of major Silurian Outcrops in Eastern Wisconsin Peninsula Park from both top and bottom Ephraim Sven’s Overlook Door County – Fish Creek Niagara Escarpment in the background Door Co Shoreline Cave Point near Jacksonport - Door Co Cave Point - 2013 Cave Point - Door Co - 2013 during low lake levels Jean Nicolet 1634 overlooking Green Bay WI while standing on the Ledge Wequiock Falls near Green Bay WI. -

Ground-Water Conditions in the Milwaukee-Waukesha Area, Wisconsin

Ground-Water Conditions in the Milwaukee-Waukesha Area, Wisconsin GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1229 Ground-Water Conditions in the Milwaukee -Waukesha Area, Wisconsin By F. C. FOLEY, W. C. WALTON, and W. J. DRESCHER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1229 A progress report, with emphasis on the artesian sandstone aquifer. Prepared in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1953 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director f For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 70 cents CONTENTS Page Abstract.............................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction........................................................................................................................ 3 Purpose and scope of report.................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments...................................................................................................... 5 Description of the area............................................................................................ 6 Previous reports........................................................................................................ 6 Well-numbering system.............................................................................................. 7 Stratigraphy....................................................................................................................... -

Wisconsin Wisconsin

LAKE WINNEBAGO WATERSHED (WI) HUC:04030103 Wisconsin Wisconsin Rapid Watershed Assessment Lake Winnebago Watershed Rapid watershed assessments provide initial estimates of where conservation investments would best address the concerns of landowners, conservation districts, and other community organizations and stakeholders. These assessments help landowners and local leaders set priorities and determine the best actions to achieve their goals. Wisconsin October 2007 The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To fi le a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Offi ce of Civil Rights, Room 326W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington DC 20250-9410, or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. 1 LAKE WINNEBAGO WATERSHED (WI) HUC:04030103 CONTENTS o g a b e n n i W e k a L INTRODUCTION 3 COMMON RESOURCE AREA DESCRIPTION 4 ELEVATION MAP 5 LAND USE AND ANNUAL PRECIPITATION MAPS 6 ASSESSMENT OF WATERS 7 SOILS 9 DRAINAGE CLASSIFICATION 10 FARMLAND CLASSIFICATION 11 HYDRIC SOILS 12 LAND CAPABILITY CLASSIFICATION 13 PRS AND OTHER DATA 14 CENSUS AND SOCIAL DATA (RELEVANT) 15 ECOLOGICAL LANDSCAPE 16 RESOURCE CONCERNS 17 WATERSHED PROJECTS, 17 STUDIES, MONITORING, ETC WATERSHED ASSESSMENT 17 PARTNER GROUPS 18 FOOTNOTES/BIBLIOGRAPHY 19 2 LAKE WINNEBAGO WATERSHED (WI) HUC:04030103 1 INTRODUCTION The Lake Winnebago watershed is located in east central Wisconsin and surrounds the largest lake in the state, Lake Winnebago, which covers 137,708 acres. -

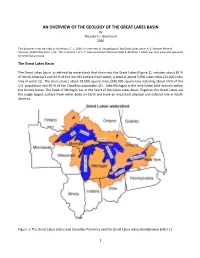

AN OVERVIEW of the GEOLOGY of the GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J

AN OVERVIEW OF THE GEOLOGY OF THE GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J. Bornhorst 2016 This document may be cited as: Bornhorst, T. J., 2016, An overview of the geology of the Great Lakes basin: A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum, Web Publication 1, 8p. This is version 1 of A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum Web Publication 1 which was only internally reviewed for technical accuracy. The Great Lakes Basin The Great Lakes basin, as defined by watersheds that drain into the Great Lakes (Figure 1), includes about 85 % of North America’s and 20 % of the world’s surface fresh water, a total of about 5,500 cubic miles (23,000 cubic km) of water (1). The basin covers about 94,000 square miles (240,000 square km) including about 10 % of the U.S. population and 30 % of the Canadian population (1). Lake Michigan is the only Great Lake entirely within the United States. The State of Michigan lies at the heart of the Great Lakes basin. Together the Great Lakes are the single largest surface fresh water body on Earth and have an important physical and cultural role in North America. Figure 1: The Great Lakes states and Canadian Provinces and the Great Lakes watershed (brown) (after 1). 1 Precambrian Bedrock Geology The bedrock geology of the Great Lakes basin can be subdivided into rocks of Precambrian and Phanerozoic (Figure 2). The Precambrian of the Great Lakes basin is the result of three major episodes with each followed by a long period of erosion (2, 3). Figure 2: Generalized Precambrian bedrock geologic map of the Great Lakes basin. -

Exploring Wisconsin Geology

UW Green Bay Lifelong Learning Institute January 7, 2020 Exploring Wisconsin Geology With GIS Mapping Instructor: Jeff DuMez Introduction This course will teach you how to access and interact with a new online GIS map revealing Wisconsin’s fascinating past and present geology. This online map shows off the state’s famous glacial landforms in amazing detail using new datasets derived from LiDAR technology. The map breathes new life into hundreds of older geology maps that have been scanned and georeferenced as map layers in the GIS app. The GIS map also lets you Exploring Wisconsin Geology with GIS mapping find and interact with thousands of bedrock outcrop locations, many of which have attached descriptions, sketches, or photos. Tap the GIS map to view a summary of the surface and bedrock geology of the area chosen. The map integrates data from the Wisconsin Geological & Natural History Survey, the United States Geological Survey, and other sources. How to access the online map on your computer, tablet, or smart phone The Wisconsin Geology GIS map can be used with any internet web browser. It also works on tablets and on smartphones which makes it useful for field trips. You do not have to install any special software or download an app; The map functions as a web site within your existing web browser simply by going to this URL (click here) or if you need a website address to type in enter: https://tinyurl.com/WiscoGeology If you lose this web site address, go to Google or any search engine and enter a search for “Wisconsin Geology GIS Map” to find it. -

3-D Window Into Wisconsin's Geology

LESSON PLAN | FOCUS ON GEOLOGY 3-D window into Wisconsin’s geology M. Carol McCartney, Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey | 2019 Concepts to learn This activity is designed to engage students in asking questions about the shape of the land surface in Wisconsin using the 3-D Wisconsin map. Students will: ❚ Describe features in maps. ❚ Identify topographic features and understand geo- logic process that affected their formation. ❚ List observations and interpretations, and draw conclusions about processes that shaped the land surface. Background Figure 1. The 3-D Wisconsin poster, Look at the 3-D Wisconsin map wearing 3-D glasses. available at wgnhs.org. What do you notice? What makes you wonder? What do you hope your students will want to know 3-D Wisconsin map. The map has text that describes more about? each of the numbered features; the website that sup- The 3-D Wisconsin map can be a portal to under- ports the map contains additional information about standing Wisconsin’s geologic story. The landscape each feature. That site is at wgnhs.org/wisconsin- that jumps off the page of the 3-D map was shaped geology/major-landscape-features. by geologic processes that started around 3 billion There are many more features on the landscape years ago and that continue today—with some pretty beyond the 14 described on the map. We include ad- spectacular events along the way. ditional resources for you or your students to further Details often noticed (numbers refer to numbered investigate how Wisconsin was shaped. descriptions from -

Radisson's Two Western Journeys

RADISSON'S TWO WESTERN JOU RN EYS When the French in the beginning of the seventeenth century took possession of the St. Lawrence Valley, the acquisition does not seem to have been considered an event of major importance. The population of the home coun try was not yet so dense as to demand new territory for expansion. For many years, moreover, there was doubt that agriculture would prove profitable In a climate so much more severe than that of France. The acquisition of Can ada was therefore considered of dubious value except by a few missionaries, and the royal government was very slow in granting any assistance for the safety or progress of the new colony. Soon, however, it was discovered that this American possession could supply one great need of the home coun try, and that was furs. Particularly was it rich in beaver, which was in great demand for beaver hats—the headgear demanded by fashion. The fur trade therefore became the mainstay of the colony and gained for it the few crumbs of favor that it received. For many years this trade was confined to the small tribes on the rivers that empty into the St. Lawrence from the north. Then came a larger supply of furs from the more populous Huron country and from the Ottawa on Manitoulln Island. Each spring when the Indians brought in their canoes filled with peltries, small fairs were held in Montreal and Three Rivers, where the natives exchanged their furs for the utensils, tools, orna ments, and dainties that the French merchants and habit ants had to offer. -

2. Blue Hills 2001

Figure 1. Major landscape regions and extent of glaciation in Wisconsin. The most recent ice sheet, the Laurentide, was centered in northern Canada and stretched eastward to the Atlantic Ocean, north to the Arctic Ocean, west to Montana, and southward into the upper Midwest. Six lobes of the Laurentide Ice Sheet entered Wisconsin. Scale 1:500,000 10 0 10 20 30 PERHAPS IT TAKES A PRACTICED EYE to appreciate the landscapes of Wisconsin. To some, MILES Wisconsin landscapes lack drama—there are no skyscraping mountains, no monu- 10 0 10 20 30 40 50 mental canyons. But to others, drama lies in the more subtle beauty of prairie and KILOMETERS savanna, of rocky hillsides and rolling agricultural fi elds, of hillocks and hollows. Wisconsin Transverse Mercator Projection The origin of these contrasting landscapes can be traced back to their geologic heritage. North American Datum 1983, 1991 adjustment Wisconsin can be divided into three major regions on the basis of this heritage (fi g. 1). The fi rst region, the Driftless Area, appears never to have been overrun by glaciers and 2001 represents one of the most rugged landscapes in the state. This region, in southwestern Wisconsin, contains a well developed drainage network of stream valleys and ridges that form branching, tree-like patterns on the map. A second region— the northern and eastern parts of the state—was most recently glaciated by lobes of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which reached its maximum extent about 20,000 years ago. Myriad hills, ridges, plains, and lakes characterize this region. A third region includes the central to western and south-central parts of the state that were glaciated during advances of earlier ice sheets. -

![Map of the Lake Winnebago System [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8115/map-of-the-lake-winnebago-system-pdf-348115.webp)

Map of the Lake Winnebago System [PDF]

Lake Winnebago System (includes tributaries up to the first dam or barrier impassable to fish) SHAWANO Spencer Creek Shawano Willow Dam Creek School W Branch Shioc River Mill Rose Section Creek Pella Dam Brook Creek Schoenick Slab City Lake Creek Green East Branch Bay Clintonville Shioc River Dam Wolf River Mink Pigeon Creek River Herman WAUPACA Shioc Creek River Embarrass Black River Toad Creek Creek Scandinavia Millpond Dam Ogdensburg Millpond Dam Manawa Peterson S Branch Millpond Dam OUTAGAMIE Creek Little Wolf River N Fork S Branch Little Wolf Little Wolf River Sannes River BROWN Skunk Bear Creek Lake Lake Bear Creek Weyauwega Fox River Millpond Dam Black Otter Lake Waupaca Dam River Spencer Walla Walla Lake Creek Rat Little Lake Austin Hatton River Creek Creek Alder Butte des Morts LakeCreek Magdanz Poygan Creek Lake Arrowhead WAUSHARA Poy Sippi Winneconne Creek Millpond Dam Pine River Lake Daggets Butte Creekdes Morts Neshkoro Willow Millpond Dam Creek Pumpkinseed Spring Creek Creek Lake Sawyer Auroraville Waukau Winnebago Creek Millpond Dam Fox River Creek WINNEBAGO White River Barnes Creek Germania Rush Lake Puchyan Marsh Dam River Black Snake Creek MARQUETTE Creek W Branch Green Lake Fond du Lac Outlet Dam Mecan River River Oxford Montello Millpond River Dam GREEN Dam Lake Puckaway LAKE E Branch Buffalo Fond du Lac River Lake Parsons Creek Neenah Grand Campground Creek River Kingston Creek Fox River Dam COLUMBIA Dam or impassable barrier 6/07 Park Swan Lake Dam Lake. -

Wisconsin Great Lakes Chronicle 2019 CONTENTS

Wisconsin Great Lakes Chronicle 2019 CONTENTS Foreword . 1 Governor Tony Evers Regional Maritime Strategy . 2 Mike Friis Water Resources and LiDAR in Wisconsin . 4 Jim Giglierano Bay Beach Restoration . 6 Dan Ditscheit Fresh Coast Resource Center . 8 Christopher Schultz and Jacob Fincher Apostle Islands: Partnering for Accessibility . 10 Mark R. Peterson Managing Visitor Use in Coastal Protected Areas . 12 Lauren Leckwee Coastal Processes Manual . 14 Yi Liu 2019 Wisconsin Coastal Management Program Grants . 16 Acknowledgements . 20 On the Cover Peninsula State Park, Department of Tourism FOREWORD Governor Tony Evers Dear Readers: Welcome to the 2019 regional economy. This is among the many reasons into Lake Michigan and Lake Superior, my edition of Wisconsin why these waters are so important, and why it is administration, Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes and I are Great Lakes Chronicle one of my top priorities as governor is to protect working hard to ensure our water resources can which highlights our natural resources and ensure our water is clean, continue supporting our economies, sustaining important efforts to safe, usable, and enjoyable for generations to come. our families, and helping our businesses thrive. conserve, protect, This year, I am also honored to be leading the I hope you enjoy this year’s edition of Wisconsin and restore our Great Great Lakes St. Lawrence Governors & Premiers Great Lakes Chronicle celebrating the good work Lakes and shorelines on initiatives to improve the quality of the and dedication of so many folks across our across our state. Great Lakes and enhance our regional economy. state. Although we are taking significant steps to From drinking water to trade to outdoor We recently adopted resolutions to reduce protect the Great Lakes, we know that there is recreation, the Great Lakes have played a critically drinking water contaminants and reaffirmed much work yet to do.