Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resourcing Sustainable Church: a Time to Change - Together

RESOURCING SUSTAINABLE CHURCH: A TIME TO CHANGE - TOGETHER Transforming lives in Greater Lincolnshire 1 Foreword from The Bishop of Lincoln Returning to Lincoln after almost two years’ absence gives me the opportunity to see and evaluate the progress that has been made to address the issues we face as a diocese. Many of the possibilities that are placed before you in this report were already under discussion in 2019. What this report, and the work that lies behind it, does is to put flesh on the bones. It gives us a diocese the opportunity to own up to and address the issues we face at this time. I am happy strongly to recommend this report. It comes with my full support and gratitude to those who have contributed so far. What it shows is that everything is possible if we trust in God and each other. Of course, this is only a first step in a process of development and change. Much as some of us, including me at times, might like to look back nostalgically to the past – the good news is that God is calling us into something new and exciting. What lies ahead will not be easy – as some hard decisions will need to be taken. But my advice is that there will never be a better opportunity to work together to uncover and build the Kingdom of God in Greater Lincolnshire. I urge the people of God in this diocese to join us on this journey. +Christopher Lincoln: Bishop of Lincoln 2 Introduction Resourcing Sustainable Church: A Time to Change - Together sets a vision for a transformed church. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2021

PORVOO PRAYER DIARY 2021 The Porvoo Declaration commits the churches which have signed it ‘to share a common life’ and ‘to pray for and with one another’. An important way of doing this is to pray through the year for the Porvoo churches and their Dioceses. The Prayer Diary is a list of Porvoo Communion Dioceses or churches covering each Sunday of the year, mindful of the many calls upon compilers of intercessions, and the environmental and production costs of printing a more elaborate list. Those using the calendar are invited to choose one day each week on which they will pray for the Porvoo churches. It is hoped that individuals and parishes, cathedrals and religious orders will make use of the Calendar in their own cycle of prayer week by week. In addition to the churches which have approved the Porvoo Declaration, we continue to pray for churches with observer status. Observers attend all the meetings held under the Agreement. The Calendar may be freely copied or emailed for wider circulation. The Prayer Diary is updated once a year. For corrections and updates, please contact Ecumenical Officer, Maria Bergstrand, Ms., Stockholm Diocese, Church of Sweden, E-mail: [email protected] JANUARY 3/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Sarah Mullally, Bishop Graham Tomlin, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Rob Wickham, Bishop Jonathan Baker, Bishop Ric Thorpe, Bishop Joanne Grenfell. Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Olav Fykse Tveit, Bishop Herborg Oline Finnset 10/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Jukka Keskitalo Church of Norway: Diocese of Sør-Hålogaland (Bodø), Bishop Ann-Helen Fjeldstad Jusnes Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015 JANUARY 4/1 Church of England: Diocese of Chichester, Bishop Martin Warner, Bishop Mark Sowerby, Bishop Richard Jackson Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Mikkeli, Bishop Seppo Häkkinen 11/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Richard Chartres, Bishop Adrian Newman, Bishop Peter Wheatley, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Paul Williams, Bishop Jonathan Baker Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Helga Haugland Byfuglien, Bishop Tor Singsaas 18/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Samuel Salmi Church of Norway: Diocese of Soer-Hålogaland (Bodoe), Bishop Tor Berger Joergensen Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Chris Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. 25/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Tampere, Bishop Matti Repo Church of England: Diocese of Manchester, Bishop David Walker, Bishop Chris Edmondson, Bishop Mark Davies Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015 FEBRUARY 1/2 Church of England: Diocese of Birmingham, Bishop David Urquhart, Bishop Andrew Watson Church of Ireland: Diocese of Cork, Cloyne and Ross, Bishop Paul Colton Evangelical Lutheran Church in Denmark: Diocese of Elsinore, Bishop Lise-Lotte Rebel 8/2 Church in Wales: Diocese of Bangor, Bishop Andrew John Church of Ireland: Diocese of Dublin and Glendalough, Archbishop Michael Jackson 15/2 Church of England: Diocese of Worcester, Bishop John Inge, Bishop Graham Usher Church of Norway: Diocese of Hamar, Bishop Solveig Fiske 22/2 Church of Ireland: Diocese -

Bishop's July 2020 Letter

The Bishops’ Office July 2020 Dear school communities, While it is not possible to ask each of you how you are, please know that we have prayed for our school communities, both pupils and teachers during this unusual and hard time. Our prayers have been for those in a classroom and also at home. In the past few months we have all had some questions and concerns - it is important that we always share these with others. Thankfully, we have also had people to keep us safe, people to care for us. We have seen that care can happen in many ways. Our message to you is about this word. Care is a word with four letters, so it is a small word but we need to remember that it has a big effect on people and can leave them smiling. As each of us cares for others we can show God's love. At first in lockdown a sign of caring was a rainbow often in a house window or a cuddly toy. Now, we may be able to show we care to more people. That may happen in our bubble of people or with a wave and a smile or helping someone with something bigger. To care is something we can all do in small ways. No matter how small when we care we are showing something that is big. We are showing God's love for each of us. A good example of caring are your teachers and school staff. They have cared for you and others throughout the lockdown. -

Thoughts, Notices and Reminders August 5 2018

Thoughts, notices and reminders August 5 2018 John Birch Please feel free to contact Fr. Stephen at any time, but please remember that his usual day off is Friday. Telephone: 01522 525621 mobile: 0794 371 5279 e-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.stjohnthebaptistparishchurch.org.uk Any items for this weekly sheet should be received by Rachel Fleshbourne no later than Wednesday evening. If you would like to receive this weekly sheet by email, please e-mail Rachel: [email protected] THE PRAYER PAGE Saint’s Day Prayer in the parish Prayer in the diocese Sunday Our parish visitors THE SCRIPTURE UNION Trinity 10 Residents of: Burwell Close, Cabourne BEACH MISSION AT SUTTON- Avenue, Carlton Grove, Carlton Walk ON-SEA Monday Flower arrangers, Community Larder FOR DISCIPLES THROUGHOUT OUR DIOCESE TO SEE MORE Transfiguration Residents of: Chatterton Avenue, CLEARLY WHO JESUS IS, AND TO Clarendon Gardens, Clarendon View, BE SENT OUT IN MINISTRY IN THE David Avenue LIGHT OF THAT VISION Tuesday Staff and users of the church hall CHURCH SCHOOLS IN John Mason Paul Musson, Olive Musson, Liz Straw, THE LAWRES DEANERY Neale Priest the hall committee and all hall users Residents of: Dunholme Court, Dunston Close, Edendale Gardens, Edendale View Wednesday The lunch club; Guides and Brownies THE ARCHDEACON OF St Dominic Sue Fleshbourne and the lunch club LINCOLN Founder of the team The Ven. Gavin Kirk Order of Residents of: Edlington Close, Epworth Preachers View, Ermine Close, Escombe View Thursday -

Prayer Diary

Sunday 30 MAY Trinity Sunday New Diocesan Office in Lowesmoor Please pray for all DBF For many years, the Diocesan staff during this unsettling Office has been located in the time, in particular for those Old Palace and it has been a whose role has been real privilege to work in such a made redundant by the beautiful place. However, it is an move and those who find expensive building to run, and it is change difficult. important that we support mission and ministry around the diocese as cost-effectively as we can. Area Dean of Worcester Deanery: Diane Cooksey In 2019, Diocesan Synod agreed Lay Chair: that we should look to move if it would generate very substantial savings. Sadly, Rob Pearce we came to the conclusion that moving was the right thing to do. It will save around £200,000 a year – enough to cover the costs of three full-time clergy Hereford: posts around the diocese. Bishop Richard Jackson Although we have not found the right long-term home, for the next three to five La Iglesia Anglicana de Mexico: Vacant years, we are staying in central Worcester, having taken out a lease on a building The Latvian Evangelical Lutheran in Lowesmoor Wharf. Church Abroad: Wherever we are located, as a diocesan support hub, our core purpose remains – Archbishop Lauma Zušēvica to serve all in our parishes as best we can, to enable your mission and ministry to The Lusitanian Church (Portugal): be as fruitful as possible. Bishop José Jorge Pina Cabral Mon 31 Russell’s Hall Hospital Canberra & Goulburn (Australia): M Pray for the staff, patients and volunteers at Russell’s Hall Hospital in Dudley, Bishop Mark Short particularly for the chaplaincy team. -

The Bishops' Office

The Bishops’ Office 28 May 2021 Dear Colleagues, This letter comes with greetings for Trinity Sunday. As we leave the great series of seasons that began with Advent and enter Ordinary Time, this seems an opportune moment to clarify our hopes for the rest of 2021 and into 2022 with respect to Resourcing Sustainable Church (RSC). This is because our implementation of RSC has to be part of our ‘ordinary’ mission and ministry from now on. We wrote earlier in the month more generally about RSC. This letter is to focus on some specifics and comes with a link to the full RSC document and with a shorter introductory guide that might be helpful for your congregations. Diocesan Synod has commended the following Resourcing Sustainable Church processes: 1 Church Type self-reflection. Starting in June 2021 and through the summer until September, every church community is invited to reflect on its strengths, opportunities, concerns and weaknesses. Resources will be offered to help with this, but a basic initial framework can be found in the full RSC document beginning at page 26. This is a vocational conversation for each church, which will help every parish to take part in what happens next. The conversation/reflection can be led by the incumbent or by delegated officers/ministers such as church wardens. The full RSC report can be found at https://www.lincoln.anglican.org/links 2 Identifying and building partnerships. Beginning in September 2021 and (if necessary) lasting until autumn 2022, churches, benefices, deaneries and groupings of deaneries (Deanery Partnerships) will discuss how to identify and build patterns of collaboration. -

Religious Self-Fashioning As a Motive in Early Modern Diary Keeping: the Evidence of Lady Margaret Hoby's Diary 1599-1603, Travis Robertson

From Augustine to Anglicanism: The Anglican Church in Australia and Beyond Proceedings of the conference held at St Francis Theological College, Milton, February 12-14 2010 Edited by Marcus Harmes Lindsay Henderson & Gillian Colclough © Contributors 2010 All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. First Published 2010 Augustine to Anglicanism Conference www.anglicans-in-australia-and-beyond.org National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Harmes, Marcus, 1981 - Colclough, Gillian. Henderson, Lindsay J. (editors) From Augustine to Anglicanism: the Anglican Church in Australia and beyond: proceedings of the conference. ISBN 978-0-646-52811-3 Subjects: 1. Anglican Church of Australia—Identity 2. Anglicans—Religious identity—Australia 3. Anglicans—Australia—History I. Title 283.94 Printed in Australia by CS Digital Print http://www.csdigitalprint.com.au/ Acknowledgements We thank all of the speakers at the Augustine to Anglicanism Conference for their contributions to this volume of essays distinguished by academic originality and scholarly vibrancy. We are particularly grateful for the support and assistance provided to us by all at St Francis’ Theological College, the Public Memory Research Centre at the University of Southern Queensland, and Sirromet Wines. Thanks are similarly due to our colleagues in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Southern Queensland: librarians Vivienne Armati and Alison Hunter provided welcome assistance with the cataloguing data for this volume, while Catherine Dewhirst, Phillip Gearing and Eleanor Kiernan gave freely of their wise counsel and practical support. -

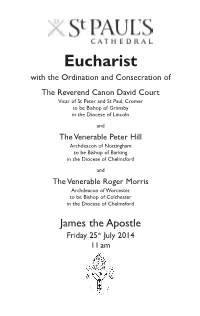

Consecration

Eucharist with the Ordination and Consecration of The Reverend Canon David Court Vicar of St Peter and St Paul, Cromer to be Bishop of Grimsby in the Diocese of Lincoln and The Venerable Peter Hill Archdeacon of Nottingham to be Bishop of Barking in the Diocese of Chelmsford and The Venerable Roger Morris Archdeacon of Worcester to be Bishop of Colchester in the Diocese of Chelmsford James the Apostle Friday 25 th July 2014 11 am WELCOME TO ST PAUL’S CATHEDRAL We are a Christian church within the Anglican tradition (Church of England) and we welcome people of all Christian traditions as well as people of other faiths and people of little or no faith. Christian worship has been offered to God here for over 1400 years. By worshipping with us today, you become part of that living tradition. Our regular worshippers, supported by nearly 150 members of staff and a large number of volunteers, make up the cathedral community. We are committed to the diversity, equal opportunities and personal and spiritual development of all who work and worship here because we are followers of Jesus Christ. We are a Fairtrade Cathedral and use fairly traded communion wine at all celebrations of the Eucharist. This order of service is printed on sustainably-produced paper. You are welcome to take it away with you but, if you would like us to recycle it for you, please leave it on your seat. Thank you for being with us today. If you need any help, please ask a member of staff. Please be assured of our continuing prayers for you when you go back to your homes and places of worship. -

January to March 2020 the Anglican Communion's Cycle of Prayer Is A

Anglican Communion Cycle of Prayer – January to March 2020 The Anglican Communion’s Cycle of Prayer is a much-used and highly valued resource that unites Anglicans around the world in prayer for each other. We hope to relaunch the interactive Anglican Cycle of Prayer early in 2020. In this interim listing, which covers the first quarter of 2020, we name only the diocesan bishop, in a change to our previous practice. We ask that you pray for the people, clergy and bishop of the named dioceses. Wednesday, 1 January 2020 Lagos (Nigeria) The Right Revd Humphery Olumakaiye Lagos Mainland (Nigeria) The Right Revd B C Akinpelu Johnson Lagos West (Nigeria) The Right Revd James Olusola Odedeji Thursday, 2 January 2020 Lahore (Pakistan) The Right Revd Irfan Jamil South Western Brazil (Brazil) The Right Revd Francisco De Assis Da Silva Southeast Florida (The Episcopal Church) The Right Revd Peter Eaton Friday, 3 January 2020 Lainya (South Sudan) vacant Southeastern Mexico (Mexico) The Right Revd Benito Juarez-Martinez Saturday, 4 January 2020 Lake Malawi (Central Africa) The Right Revd Francis Kaulanda Southern Brazil (Brazil) The Right Revd Humberto Maiztegue Goncalves Gippsland (Australia) The Right Revd Dr Richard Treloar Sunday, 5 January 2020 Pray for the Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia The Most Revd Philip Richardson - Bishop of Taranaki and Primate The Most Revd Don Tamihere - Pihopa o Aotearora and Primate The Most Revd Fereimi Cama - Bishop of Polynesia and Primate Monday, 6 January 2020 Lake Rukwa (Tanzania) The Right -

St Francis. a History of the Newest Church in Cleethorpes

ST FRANCIS. A HISTORY OF THE NEWEST CHURCH IN CLEETHORPES. The Beacon Hill Estate was built up gradually during the late 1940’s to the mid 1960’s and comprised of a mixture of semi-detached family houses, bungalows and flats, some privately owned and some owned by the council (now Shoreline). The inhabitants included many young families as well as elderly people. To cater for this new ever expanding estate the Revd Canon Richard Crookes at St Peter’s Church in Cleethorpes decided that a new church needed to be built to bring the word of God to the estate. The land for the church had been set aside when the estate was planned and had been given by Sidney Sussex College. Plans were passed in 1956 but had lapsed so in 1961 it was decided to build a dual purpose building which was sourced from a company in Wakefield called Lanner’s. The construction method meant it could be built in six months as the sections were produced at the factory and erected on site on a prepared foundation. The plan was to use the building as a church and hall until a “proper” church could be built on adjacent land at a later date. The fundraising for the new church was led energetically and memorably by the curate at St Peters at the time, the Revd Edward Harrison who had arrived in Cleethorpes in 1959 and, at a time of great recession was certainly not an easy task to undertake. Many can remember him at his happiest sitting on an upturned wooden box in the open streets of Grimsby and Cleethorpes, playing the accordion and entertaining children with his glove puppets while collection donations for the many charities he supported throughout his life. -

A Letter to the People of the Diocese – 29 July 2021

The Bishops’ Office A letter to the people of the Diocese 29 July 2021 Dear Friends, As July turns to August, we want to write to wish you as good a summer as possible in these still extraordinary times, and to thank you, again, for your ministry, your prayer, and your faithfulness during these pandemic months. We realise that travel is still restricted, that the Covid-19 virus is still active, and that lives have been marked by infection and by loss. We know that the workload that you have carried during lockdown has now mutated into a different kind of workload, as we catch up with pastoral offices such as baptisms and marriages, and as we try to make good decisions about recovery and rebuilding. We are also very mindful that Diocesan Synod’s overwhelming endorsement of Resourcing Sustainable Church - A Time to Change Together means that over the next few months, and especially into the autumn, there will be further reflection to undertake and decisions to make, as we build our future together. For all these reasons, we hope that, wherever possible, you will take time over the next few weeks to relax and to recharge. Please be as kind to yourself, to your loved ones, and to each other, as you can possibly be. We know that holidays away from home may not be achievable - indeed, all three of us are essentially having ‘staycations’ this year - but we do hope that you will be able to change pace and to do something different, however small that may be.