Food Security and Environment Conservation Through Sustainable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Modeling Climate Change Impacts on Crop Water Demand, Middle Awash River Basin, Case Study of Berehet Woreda

© 2021 The Authors Water Practice & Technology Vol 16 No 3 864 doi: 10.2166/wpt.2021.033 Modeling climate change impacts on crop water demand, middle Awash River basin, case study of Berehet woreda Negash Tessema Robaa,*, Asfaw Kebede Kassab and Dame Yadeta Geletac a Water Resources and Irrigation Engineering Department, Haramaya Institute of Technology, Haramaya University, P.O. Box 138, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia b Hydraulic and Water Resources Engineering Department, Haramaya Institute of Technology, Haramaya University, P.O. Box 138, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia c Natural Resources Management Department, College of Dry Land Agriculture, Samara University, P.O. Box 132, Samara, Ethiopia *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Climate change mainly affects crops via impacting evapotranspiration. This study quantifies climate change impacts on evapotranspiration, crop water requirement, and irrigation water demand. Seventeen GCMs from the MarkSim-GCM were used for RCP 4.5 and 8.5 scenarios for future projection. A soil sample was collected from 15 points from the maize production area. Based on USDA soil textural classification, the soil is classified as silt loam (higher class), clay loam (middle class), and clay loam (lower class). The crop growing season onset and offset were determined using the Markov chain model and compared with the farmer’s indigenous experience. The main rainy season (Kiremt) starts during the 1st meteorological decade of June for baseline period and 2nd decade to 3rd decade of June for both RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 of near (2020s) and mid (2050s) future period. The offset date is in the range of 270 (base period), RCP 4.5 (278, 284), and RCP 8.5 (281, 274) DOY for baseline, near, and mid future. -

Thesis Assessment of Gullele Botanic Gardens

THESIS ASSESSMENT OF GULLELE BOTANIC GARDENS CONSERVATION STRATEGY IN ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA RESEARCH FROM THE PEACE CORPS MASTERS INTERNATIONAL PROGAM Submitted by Carl M. Reeder Department of Forest and Rangeland Stewardship In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2013 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Melinda Laituri Paul Evangelista Jessica Davis Robert Sturtevant Copyright by Carl M. Reeder 2013 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ASSESSMENT OF GULLELE BOTANIC GARDENS CONSERVATION STRATEGY IN ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA RESEARCH FROM THE PEACE CORPS MASTERS INTERNATIONAL PROGAM Monitoring of current and future conditions is critical for a conservation area to quantify results and remain competitive against alternative land uses. This study aims to monitor and evaluate the objectives of the Gullele Botanic Gardens (GBG) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The following report advances the understanding of existing understory and tree species in GBG and aims to uncover various attributes of the conservation forest. To provide a baseline dataset for future research and management practices, this report focused on species composition and carbon stock analysis of the area. Species-specific allometric equations to estimate above-ground biomass for Juniperus procera and Eucalyptus globulus are applied in this study to test the restoration strategy and strength of applied allometry to estimate carbon stock of the conservation area. The equations and carbon stock of the forest were evaluated with the following hypothesis: Removal of E. globulus of greater than 35cm DBH would impact the carbon storage (Mg ha-1) significantly as compared to the overall estimate. Conservative estimates found E. -

Protecting Land Tenure Security of Women in Ethiopia: Evidence from the Land Investment for Transformation Program

PROTECTING LAND TENURE SECURITY OF WOMEN IN ETHIOPIA: EVIDENCE FROM THE LAND INVESTMENT FOR TRANSFORMATION PROGRAM Workwoha Mekonen, Ziade Hailu, John Leckie, and Gladys Savolainen Land Investment for Transformation Programme (LIFT) (DAI Global) This research paper was created with funding and technical support of the Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights, an initiative of Resource Equity. The Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights is a community of learning and practice that works to increase the quantity and strengthen the quality of research on interventions to advance women’s land and resource rights. Among other things, the Consortium commissions new research that promotes innovations in practice and addresses gaps in evidence on what works to improve women’s land rights. Learn more about the Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights by visiting https://consortium.resourceequity.org/ This paper assesses the effectiveness of a specific land tenure intervention to improve the lives of women, by asking new questions of available project data sets. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to investigate threats to women’s land rights and explore the effectiveness of land certification interventions using evidence from the Land Investment for Transformation (LIFT) program in Ethiopia. More specifically, the study aims to provide evidence on the extent that LIFT contributed to women’s tenure security. The research used a mixed method approach that integrated quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitative information was analyzed from the profiles of more than seven million parcels to understand how the program had incorporated gender interests into the Second Level Land Certification (SLLC) process. -

Plant Collections from Ethiopia Desalegn Desissa & Pierre Binggeli

Miscellaneous Notes & Reports in Natural History, No 001 Ecology, Conservation and Resources Management 2003 Plant collections from Ethiopia Desalegn Desissa & Pierre Binggeli List of plants collected by Desalegn Desissa and Pierre Binggeli as part of the biodiversity assessment of church and monastery vegetation in Ethiopia in 2001-2002. The information presented is a slightly edited version of what appears on the herbarium labels (an asci-delimited version of the information is available from [email protected]). Sheets are held at the Addis Ababa and Geneva herberia. Abutilon longicuspe Hochst. ex A. Rich Malvaceae Acacia etbaica Schweinf. Fabaceae Desalgen Desissa & Pierre Binggeli DD416 Desalegn Desissa & Pierre Binggeli DD432 Date: 02-01-2002 Date: 25-01-2002 Location: Ethiopia, Shewa, Zena Markos Location: Ethiopia, Tigray, Mekele Map: 0939A1 Grid reference: EA091905 Map: 1339C2 Grid reference: Lat. 09º52’ N Long. 39º04’ E Alt. 2560 m Lat. 13º29' N Long. 39º29' E Alt. 2150 m Site: Debir and Dey Promontary is situated 8 km to the West of Site: Debre Genet Medihane Alem is situated at the edge of Mekele Inewari Town. The Zena Markos Monastery is located just below Town at the base of a small escarpment. The site is dissected by a the ridge and overlooks the Derek Wenz Canyon River by 1200 m. stream that was dry at the time of the visit. For site details go to: The woodland is right below the cliff on a scree slope. Growing on a http://members.lycos.co.uk/ethiopianplants/sacredgrove/woodland.html large rock. For site details go to: Vegetation: Secondary scrubby vegetation dominated by Hibiscus, http://members.lycos.co.uk/ethiopianplants/sacredgrove/woodland.html Opuntia, Justicia, Rumex, Euphorbia. -

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008)

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008) ma, maa (O) why? HES37 Ma 1258'/3813' 2093 m, near Deresge 12/38 [Gz] HES37 Ma Abo (church) 1259'/3812' 2549 m 12/38 [Gz] JEH61 Maabai (plain) 12/40 [WO] HEM61 Maaga (Maago), see Mahago HEU35 Maago 2354 m 12/39 [LM WO] HEU71 Maajeraro (Ma'ajeraro) 1320'/3931' 2345 m, 13/39 [Gz] south of Mekele -- Maale language, an Omotic language spoken in the Bako-Gazer district -- Maale people, living at some distance to the north-west of the Konso HCC.. Maale (area), east of Jinka 05/36 [x] ?? Maana, east of Ankar in the north-west 12/37? [n] JEJ40 Maandita (area) 12/41 [WO] HFF31 Maaquddi, see Meakudi maar (T) honey HFC45 Maar (Amba Maar) 1401'/3706' 1151 m 14/37 [Gz] HEU62 Maara 1314'/3935' 1940 m 13/39 [Gu Gz] JEJ42 Maaru (area) 12/41 [WO] maass..: masara (O) castle, temple JEJ52 Maassarra (area) 12/41 [WO] Ma.., see also Me.. -- Mabaan (Burun), name of a small ethnic group, numbering 3,026 at one census, but about 23 only according to the 1994 census maber (Gurage) monthly Christian gathering where there is an orthodox church HET52 Maber 1312'/3838' 1996 m 13/38 [WO Gz] mabera: mabara (O) religious organization of a group of men or women JEC50 Mabera (area), cf Mebera 11/41 [WO] mabil: mebil (mäbil) (A) food, eatables -- Mabil, Mavil, name of a Mecha Oromo tribe HDR42 Mabil, see Koli, cf Mebel JEP96 Mabra 1330'/4116' 126 m, 13/41 [WO Gz] near the border of Eritrea, cf Mebera HEU91 Macalle, see Mekele JDK54 Macanis, see Makanissa HDM12 Macaniso, see Makaniso HES69 Macanna, see Makanna, and also Mekane Birhan HFF64 Macargot, see Makargot JER02 Macarra, see Makarra HES50 Macatat, see Makatat HDH78 Maccanissa, see Makanisa HDE04 Macchi, se Meki HFF02 Macden, see May Mekden (with sub-post office) macha (O) 1. -

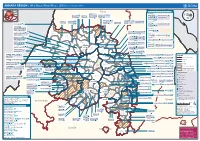

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Physico-Chemical Analysis and Determination of Various Chemical Constituents of Essential Oil in Rosa Centifolia

Pak. J. Bot., 41(2): 615-620, 2009. PHYSICO-CHEMICAL ANALYSIS AND DETERMINATION OF VARIOUS CHEMICAL CONSTITUENTS OF ESSENTIAL OIL IN ROSA CENTIFOLIA M. KHALID SHABBIR1, RAZIYA NADEEM1, HAMID MUKHTAR2, FAROOQ ANWAR1 AND MUHAMMAD W. MUMTAZ1, 1Department of Chemistry, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan 2Institute of Industrial Biotechnology, Govt. College University, Lahore 54000 Pakistan, 3Department of Chemistry, University of Gujrat, Pakistan Abstract This paper reports the isolation and characterization of essential oil of Rosa centifolia. The oil was extracted from freshly collected flower petals of R. centifolia with petroleum ether using Soxhlet apparatus. Rosa centifolia showed 0.225% concrete oil and 0.128% yield of absolute oil. Some physico-chemical properties of the extracted oil like colour, refractive index, congealing point, optical rotation, specific gravity, acid number and ester number were determined and were found to be yellowish brown, 1.454 at 340C, 15°C, -32.50 to +54.21, 0.823 at 30oC, 14.10245 and 28.1876. High- resolution gas liquid chromatographic (HR-GLC) analysis of the essential oil of R. centifolia, showed the phenethyl alcohol, geranyl acetate, geraniol and linalool as major components whereas, benzyl alcohol, benzaldehyde and citronellyl acetate were detected at trace levels. Introduction A variety of roses are generally cultivated for home and garden beautification in many parts of the world. Its rich fragrance has perfumed human history for generations (Rose, 1999). Roses contain very little essential oil but it has a wide range of applications in many industries for the scenting and flavouring purposes. It is used as perfumer in soap and cosmetics and as a flavor in tea and liquors. -

Ethiopia: Amhara Region Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Amhara region administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abrha jara ! Tselemt !Adi Arikay Town ! Addi Arekay ! Zarima Town !Kerakr ! ! T!IGRAY Tsegede ! ! Mirab Armacho Beyeda ! Debark ! Debarq Town ! Dil Yibza Town ! ! Weken Town Abergele Tach Armacho ! Sanja Town Mekane Berhan Town ! Dabat DabatTown ! Metema Town ! Janamora ! Masero Denb Town ! Sahla ! Kokit Town Gedebge Town SUDAN ! ! Wegera ! Genda Wuha Town Ziquala ! Amba Giorges Town Tsitsika Town ! ! ! ! Metema Lay ArmachoTikil Dingay Town ! Wag Himra North Gonder ! Sekota Sekota ! Shinfa Tomn Negade Bahr ! ! Gondar Chilga Aukel Ketema ! ! Ayimba Town East Belesa Seraba ! Hamusit ! ! West Belesa ! ! ARIBAYA TOWN Gonder Zuria ! Koladiba Town AMED WERK TOWN ! Dehana ! Dagoma ! Dembia Maksegnit ! Gwehala ! ! Chuahit Town ! ! ! Salya Town Gaz Gibla ! Infranz Gorgora Town ! ! Quara Gelegu Town Takusa Dalga Town ! ! Ebenat Kobo Town Adis Zemen Town Bugna ! ! ! Ambo Meda TownEbinat ! ! Yafiga Town Kobo ! Gidan Libo Kemkem ! Esey Debr Lake Tana Lalibela Town Gomenge ! Lasta ! Muja Town Robit ! ! ! Dengel Ber Gobye Town Shahura ! ! ! Wereta Town Kulmesk Town Alfa ! Amedber Town ! ! KUNIZILA TOWN ! Debre Tabor North Wollo ! Hara Town Fogera Lay Gayint Weldiya ! Farta ! Gasay! Town Meket ! Hamusit Ketrma ! ! Filahit Town Guba Lafto ! AFAR South Gonder Sal!i Town Nefas mewicha Town ! ! Fendiqa Town Zege Town Anibesema Jawi ! ! ! MersaTown Semen Achefer ! Arib Gebeya YISMALA TOWN ! Este Town Arb Gegeya Town Kon Town ! ! ! ! Wegel tena Town Habru ! Fendka Town Dera -

Final Country Report

Land Governance Assessment Framework Implementation in Ethiopia Public Disclosure Authorized Final Country Report Supported by the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared Zerfu Hailu (PhD) Public Disclosure Authorized With Contributions from Expert Investigators January, 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Extended executive summary .............................................................................................................................. 6 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 18 2. Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 19 3. The Context ................................................................................................................................................... 22 3.1 Ethiopia's location, topography and climate ........................................................................................... 22 3.2 Ethiopia's settlement pattern .................................................................................................................... 23 3.3 System of Governance and legal frameworks ........................................................................................ -

First Report About Pharmaceutical Properties and Phytochemicals Analysis of Rosa Abyssinica R

First report about pharmaceutical properties and phytochemicals analysis of Rosa abyssinica R. Br. ex Lindl. (Rosaceae) Mahmoud Fawzy Moustafa1,2* and Sulaiman Abdullah Alrumman1 1Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia 2Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, South Valley University, Qena, Egypt Abstract: In vitro antimicrobial efficacy of seven solvent extracts from leaves and hips of Saudi Arabian weed Rosa abyssinica against a variety of human pathogenic bacteria and Candida species have been evaluated using well diffusion methods. Phytochemicals present in the leaves and hips of Rosa abyssinica has been characterized using Gas Chromatogram Mass spectrometry analysis. The extracts comparative efficacy against tested microbes gained from the fresh and dry leaves exhibited more prominent activity than fresh and dry hips. The methanol, chloroform, petroleum ether, acetone and diethyl ether extracts have a greater lethal effect on pathogenic microbes than hot water extracts, while cold-water extracts showed no activity. Twenty-four phytochemicals have been characterized from ethanol extract of the leaves of Rosa abyssinica and fifteen from hips by GC-MS. The major compounds detected in the leaves were squalene (38.21%), ethane, 1,1-diethoxy- (9.65%), β-D-glucopyranose, 1,6-anhydro- (8.55%), furfural (5.50%) and 2- furancarboxaldehyde 5-(hydroxymethyl)- (5.19%). The major compounds in the hips were 2-furancarboxaldehyde 5- (hydroxymethyl)- (51.27%), β-D-glucopyranose, 1,6-anhydro- (8.18%), 4H-pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6- methyl- (7.42%), 2,5-furandione, dihydro-3-methylene- (6.79%) and furfural (5.99%). Current findings indicate that extract from leaves and hips of Rosa abyssinica and the bioactive components present could be used as pharmaceutical agents. -

Plant Inventory No. 173

Plant Inventory No. 173 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Washington, D.C., March 1969 UCED JANUARY 1 to DECEMBER 31, 1965 (N( >. 303628 to 310335) MAY 2 6 1969 CONTENTS Page Inventory 8 Index of common and scientific names 257 This inventory, No. 173, lists the plant material (Nos. 303628 to 310335) received by the New Crops Research Branch, Crops Research Division, Agricultural Research Service, during the period from January 1 to December 31, 1965. The inventory is a historical record of plant material introduced for Department and other specialists and is not to be considered as a list of plant ma- terial for distribution. The species names used are those under which the plant ma- terial was received. These have been corrected only for spelling, authorities, and obvious synonymy. Questions related to the names published in the inventory and obvious errors should be directed to the author. If misidentification is apparent, please submit an herbarium specimen with flowers and fruit for reidentification. HOWARD L. HYLAND Botanist Plant Industry Station Beltsville, Md. INVENTORY 303628. DIGITARIA DIDACTYLA Willd. var DECALVATA Henr. Gramineae. From Australia. Plants presented by the Commonwealth Scientific and In- dustrial Research Organization, Canberra. Received Jan. 8, 1965. Grown at West Ryde, Sydney. 303629. BRASSICA OLERACEA var. CAPITATA L. Cruciferae. Cabbage. From the Republic of South Africa. Seeds presented by Chief, Division of Plant and Seed Control, Department of Agricultural Technical Services, Pretoria. Received Jan. 11, 1965. Cabbage Number 20. 303630 to 303634. TRITICUM AESTIVUM L. Gramineae. From Australia. Seeds presented by the Agricultural College, Roseworthy. Received Jan. 11,1965.