Presidential Leadership in Education: 1961-1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judgement No. 92 41

Judgement No. 92 41 Judgement No. 92 (Original : English) Case No. 91: Against : The Secretary-General of Higgins the Inter-Governmental Maritime Consultative Orgauization Request for rescission of a decision of the Secretary-General of IMCO terminating the secondment of a United Nations stafl member to IMCO before its date of expiration. No rules of law dealing specifically with the rights and obligations of members of the staff of the United Nations and its specialized agencies who take up service with an organization different from the one to which they belong, whether by “loan”, ” transfer “, or “ secondment “.-Legal effect of the agreement (CO-ORDINATION/ R.430) and the Memorandum of Understanding (CO-ORD/CC/S0/91) of the Consul- tative Committee on Administrative Questions. Legal definition of ” secondment “.-Distinguished from “ transfer ” and “ loan ‘I.- Existence of three parties to a contract of secondment, namely, the releasing organization, the receiving organization and the staff member concerned.-Consent of staff member required to secondment, its duration, and the terms and conditions of employment in the receiving organization.-Terms and conditions of secondment cannot be varied unilaterally or simply by agreement between the two organizations to the detriment of the staff member.-Inapplicability of Staff Regulation 1.2 of the United hrations.- Existence of a contract of employment between IMCO and the Applicant and applicability to the Applicant of the Staff Regulations and Rules of IMCO, including IMCO Staff Regulation 9, despite the absence of a letter of appointment from IMCO.-Non-obser- vance by the Respondent of the due process to which the Applicant was entitled before termination of secondment.-Contested decision cannot be sustained. -

ORANGE COUNTY CAUFORNIA Continued on Page 53

KENNEDY KLUES Research Bulletin VOLUME II NUMBER 2 & 3 · November 1976 & February 1977 Published by:. Mrs • Betty L. Pennington 6059 Emery Street Riverside, California 92509 i . SUBSCRIPTION RATE: $6. oo per year (4 issues) Yearly Index Inc~uded $1. 75 Sample copy or back issues. All subscriptions begin with current issue. · $7. 50 per year (4 issues) outside Continental · · United States . Published: · August - November - Febr:UarY . - May .· QUERIES: FREE to subscribers, no restrictions as· ·to length or number. Non subscribers may send queries at the rate of 10¢ pe~)ine, .. excluding name and address. EDITORIAL POLICY: -The E.ditor does· not assume.. a~y responsibility ~or error .. of fact bR opinion expressed by the. contributors. It is our desire . and intent to publish only reliable genealogical sour~e material which relate to the name of KENNEDY, including var.iants! KENEDY, KENNADY I KENNEDAY·, KENNADAY I CANADA, .CANADAY' · CANADY,· CANNADA and any other variants of the surname. WHEN YOU MOVE: Let me know your new address as soon as possibie. Due. to high postal rates, THIS IS A MUST I KENNEDY KLyES returned to me, will not be forwarded until a 50¢ service charge has been paid, . coi~ or stamps. BOOK REVIEWS: Any biographical, genealogical or historical book or quarterly (need not be KENNEDY material) DONATED to KENNEDY KLUES will be reviewed in the surname· bulletins·, FISHER FACTS, KE NNEDY KLUES and SMITH SAGAS • . Such donations should be marked SAMfLE REVIEW COPY. This is a form of free 'advertising for the authors/ compilers of such ' publications~ . CONTRIBUTIONS:· Anyone who has material on any KE NNEDY anywhere, anytime, is invited to contribute the material to our putilication. -

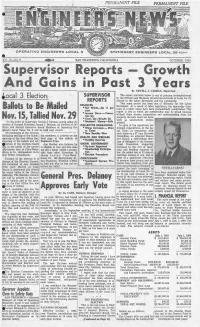

OCTOBER 1960 • • R St Rs (Conthiued Fi.·Om Page 1) Some :Sources in 1959 to 1960 ; Ary Increases for the Business

•.' _, -PERMANENT FILE '•' STATIONARY. ~ ENGfNEERS. ·. '· ... .·. -~· - .. OCTOBER,"1960 • " ~- ~- .,,.,. " J ' • •• r • • '•Ort ~ - r • :• s• "'• Past. -~ .' . --· \! . By NEWELL J. · CA~MAN, Superf isor : ·, io~aL B< Election;,, .·· ·. ;: .c. " , .' SUPElR.V.ISOR TM report-. unfolded ~ below is -~one ::. of .genuine .· accorriplfshmerit : by the Officers and Members toward improvement ·oftoc~l :N·o. 3's - .. REPORTS -~ st~tti:i-e iii: the LabOr Movement and :the community. This same p~dod _has been one of difficulty _·::1\ . :.- ~a~:-:::·-~- ·t· .. _,;·_··;_··· o~/·.:··· a-- ···- e:· < ~_:: ·· a ·ctlle:-=- .l -.-i·. · ;FiNANCES: · .. for the--Laj)or ... _. :- .. ·. ~ __1, ...:- .~ ~. '·. /: u t' Movement: As a result of labor legislation, the day-to;.day £:unc :.ye · ~q~·t W:~rt,h~Op' ll , per tions of a. labor union . · · c;ent have been.. tremendously complicated .. This · . .· .. • · . · · report is one in which · -•Income Down ;.... .Protec:- the membership m<~y be· proud because . -tici'n ·.up,·. · · · withoqt .the~r sincere --cooperation and understanding from the maj~.r,:ity tb,e task could not h<~ up-.;-:Resul!:s.Up _ve •• . Mo•~ " t5~·. l'alliid ·: Nov.,• 2~ -.>•_Cost~ '. been·· · so suec~ssfully · acc'oni- ()n the ord~i: ~ of S_up~~vis.or New ,eli. '"J~ . C~rn~a:n.; a_cting unde;, di · . • Members: , Moriey~Safe plished. · · . , r.ectlon' Qf-Ge)l'eralPresidell,t Joseph JhD_elaney~ an'electlori of' ·cott~ctrve aA.fiG~INI;i\iG - . In spite. of the significant'" ad~ · fleers and -D1§tricf Executive ·J.3oard ·.Memb€rs .of Operating . · ··wage: Increases - 'More 'd'itional expenditures of 'the1' Lo giiie$rs :· LCic<U Union ·· N:o: 3 :will b.e li~la .:ne:xtrnonth . -

A Look at Presidential Power and What Could Have Been John T

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Honors Theses University Honors Program 8-1992 The Difference One Man Makes: A Look at Presidential Power and What Could Have Been John T. Sullivan Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/uhp_theses Recommended Citation Sullivan, John T., "The Difference One Man Makes: A Look at Presidential Power and What Could Have Been" (1992). Honors Theses. Paper 60. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Difference One Man Makes: A Look at Presidential Power and What Could Have Been By John T. Sullivan University Honors Thesis Dr. Barbara Brown July 1992 A question often posed in theoretical discussions is whether or not one person can make a difference in the ebb and flow of history. We might all agree that if that one person were a President of the United states, a difference could be made; but how much? While the presidency is the single most powerful position in the U.s. federal system of government, making it a formidable force in world affairs also, most scholars agree that the presidency, itself, is very limited, structurally. The success of a president in setting the nation along a desired course rests with the ingredients brought to the position by the person elected to it. Further, many events occur outside the control of the president. Fortune or failure depends upon how the individual in office reacts to these variables. -

1 March 1961 Special Distribution

GENERAL AGREEMENT ON RESTRICTEDC/W/16 TARIFFS AND TRADE 1 March 1961 Special Distribution COUNCIL 22 February - 3 March 1961 CONCLUSIONS REACHED BY COUNCIL Drafts The following drafts of conclusions reached by the Council on certain items of its agenda are submitted for approval, (It should be understood that in the minutes of the Council's meeting these conclusions will in each case be preceded by a short statement of the question under discussion and by a note on the trend of the discussion.) Item 2: Provisional accession of Switzerland It was agreed that the consultations with Switzerland in accordance with the terms of the Declaration on the Provisional Accession of Switzerland should be continued. For this purpose, a small group of contracting parties, drawn mainly from important agricultural exporters to the Swiss market was appointed, with the following membership: Australia Netherlands Canada New ZealAnd Denmark United States France Uruguay Other contracting parties which considered that they had an important interest in the products covered by Switzerlands reservation in the Declaration would be free to participate in the work of the group. The group would meet on 6 and 7 April. It was felt that it should be possible for the group, at that meeting, to suggest a time-table for the completion of the discussions with Switzerland, after which it would submit a report either to a meeting of the Council or to a session of the CONTRACTING PARTIES, whichever was the earlier. Item5: Uruguayan import surcharges It was noted that the delegation of Uruguay had transmitted to the secretariat a list of the bound items affected by the surcharges, as well as the text of the Decree of 29 September 1960 :imposing the surcharges, end that these would be circulated to contracting parties as soon as possible, It was agreed that, in view of the limited time available, it would not be possible to deal with this item at the present meeting of the Council and that it should be discussed at the next meeting of the Council. -

The John F. Kennedy National Security Files, 1961–1963

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of National Security Files General Editor George C. Herring The John F. Kennedy National Security Files, 1961–1963 Middle East First Supplement A UPA Collection from Cover: Map of the Middle East. Illustration courtesy of the Central Intelligence Agency, World Factbook. National Security Files General Editor George C. Herring The John F. Kennedy National Security Files, 1961–1963 Middle East First Supplement Microfilmed from the Holdings of The John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts Guide by Dan Elasky A UPA Collection from 7500 Old Georgetown Road ● Bethesda, MD 20814-6126 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The John F. Kennedy national security files, 1961–1963. Middle East, First supplement [microform] / project coordinator, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels. –– (National security files) “Microfilmed from the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts.” Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Dan Elasky, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the John F. Kennedy national security files, 1961–1963. Middle East, First supplement. ISBN 1-55655-925-9 1. Middle East––Politics and government––1945–1979––Sources. 2. United States–– Foreign relations––Middle East. 3. Middle East––Foreign relations––United States. 4. John F. Kennedy Library––Archives. I. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of the John F. Kennedy national security files, 1961–1963. Middle East, First supplement. II. Series. DS63.1 956.04––dc22 2007061516 Copyright © 2007 LexisNexis, a division of Reed Elsevier -

THE JFK ASSASSINATION CHRONOLOGY Compiled by Ira David Wood III

THE JFK ASSASSINATION CHRONOLOGY Compiled by Ira David Wood III The following is a copyrighted excerpt of THE JFK ASSASSINATION CHRONOLOGY compiled by Ira David Wood III dealing with timelines and events surrounding the period of JFK’s presidency. In some instances, sources are noted - i.e. “AQOC” -an abreviation for the book, A Question Of Character. Mr. Wood is currently attempting to list all sources in anticipation of publication. January 19, 1961 Eisenhower and JFK meet at the White House for a final briefing. Eisenhower tells JFK that he must assume responsibility for the overthrow of Fidel Castro and his dangerous government, and recommends the acceleration of the proposed Cuban invasion. Says Eisenhower: “ . we cannot let the present government there go on.” AQOC Eight inches of snow falls in Washington, D.C. tonight. Traffic is snarled all over the city. After a reception, a party, and a concert at Constitution Hall, the Kennedys attend a star-studded gala at the National Guard Armory planned by Frank Sinatra. Boxes cost ten thousand dollars apiece, while individual seats go for one hundred dollars. JFK gets to bed about 4:00 A.M. AQOC January 20, 1961 JFK is sworn in as the nation’s 35th President JFK is sworn in by Chief Justice Earl Warren. JFK is the wealthiest president in American history. His private income, before taxes, is estimated at about five hundred thousand a year. On his forty-fifth birthday, his personal fortune goes up an estimated $2.5 million, in 1962, when he receives another fourth of his share in three trust funds established by his father for his children. -

NEWS a LETTERS the Root of Mankind Is Man'

NEWS A LETTERS The Root of Mankind Is Man' Printed In 100 Percent 10c A Copy VOL. 6—NO. 9 Union Shop NOVEMBER, 1961 6d in Great Britain WORKER'S JOURNAL Workers Voice Sanity By Cbarles Denby, Editor "Peace for Whom?" Amid Megaton Madness I received news of a friend in Alabama who had re cently built his family a beautiful brick home besides a highway. Several years ago whites rait him and his Thousands of people throughout the world filled the streets on October 31 to family out "accusing" him of supporting the NAACP. protest against the 50 megaton Russian monster which Khrushchev exploded in the Now he returned. Last week a' car drove up and some face of an already shocked and angry world. From Japan to Italy, from Norway one yelled to him; that they were out of gas, could he and SwedefTto France and America, the demonstrators showed their total opposition help them get to a station. When he walked out he was to Khrushchev's total disregard for human life, both born and unborn. shot down and the car sped away. In Italy, this final act of terror, after two months of That evening when I was watching the news on constant world-wide protest TV and the reporter ended his program by talking against Russia's resumption of about the need for world peace I yelled out at him as nuclea'r atmospheric testing, re though he could hear me, "Peace for whom? Go to sulted in workers tearing up Algeria, France, South Africa, Angola, or just go to and turning in their Party South USA and ask them about peace." Ask any cards—just as workers had Southern Negro worker about it or any production done .by the thousands after worker in the mines, steel mills or auto shops. -

Director of Dounreay: Mr. RR Matthews

NO.4871 March 9, 1963 NATURE 953 was educated at the Imperial College of Science and decide before the end of the year whether a prototype Technology, where he obtained the degree of B.Sc.(Eng.) nuclear ship would be built. In these circumstances, the in 1953 and five years later was awarded the degree of Government had decided that the time had come to have Ph.D. Following graduation, Dr. Clarricoats was em discussions with the shipping and shipbuilding industries ployed by the General Electric Company at Stanmore about the arrangements for such a ship. It was expected until 1958, when he was appointed lecturer in the Depart that it would be possible to decide before the end of the ment of Light Electrical Engineering in the Queen's year which reactor system should be installed in a proto University of Belfast. There he created a microwave type nuclear ship, if one is built. The Civil Lord of the research group and arranged contracts with the Depart Admiralty, Mr. C. Ian Orr-Ewing, added that the nent of Scientific and Industrial Research and the Admiralty had no present plans for building a nuclear Ministry of Aviation, which provided apparatus and powered surface vessel, but was keeping in close touch grants. In 1962, he was appointed lecturer in the with the latest developments and applying the knowle?-ge Department of Electrical Engineering at the University gained from them to studies of possible future warshIps, of Sheffield. He was awarded two premiums by the Institution of Electrical Engineers for his work on Teaching Machines and Programme Learning microwave ferrites. -

Organizational Behavior Program March 1962 PUBLICATIONS AND

Organizational Behavior Program March 1962 PUBLICATIONS AND RESEARCH DOCUMENTS - 1960 and 1961 ANDREWS. F. 1904 1630 A Study of Company Sponsored Foundations. New York: Russell Sage Founda• tion, I960, 86 pp. 1844 (See Pelz 1844) Mr. Frank Andrews has contributed substantially to a series of reports con• cerning the performance of scientific and technical personnel. Since these reports constitute an integrated series, they are all listed and described together under the name of the principle author, Dr. Donald C. Pelz, p. 4. B1AKEL0CK, E. 1604 A new look at the new leisure. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1960, 4 (4), 446-467. 1620 (With Platz, A.) Productivity of American psychologists: Quantity versus quality. American Psychologist, 1960, 15 (5), 310-312. 1696 A Durkheimian approach to some temporal problems of leisure. Paper read at the Convention of the Society for the Study of Social Problems, August I960, New York, 16 pp., mimeo. BOWERS. D. 1690R (With Patchen, M.) Factors determining first-line supervision at the Dobeckmun Company, Report II, August 1960, 43 pp., mimeo. 1803R Tabulated agency responses: Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company. September 1961, 242 pp., mimeo. 1872 Some aspects of affiliative behavior in work groups. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The University of Michigan, January 1962. 1847 Some aspects of affiliative behavior in work groups. .Abstract of doctoral dissertation, January 1962, 3 pp., mimeo. Study of life insurance agents and agencies: Methods. Report I, December 1961, 11 pp., mimeo. Insurance agents and agency management: Descriptive summary. Report II, December 1961, 41 pp.., typescript. Plus a few documents from 1962. NOTE: Some items have not been issued ISR publication numbers. -

An Examination of the Presidency of John F. Kennedy in 1963. Christina Paige Jones East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2001 The ndE of Camelot: An Examination of the Presidency of John F. Kennedy in 1963. Christina Paige Jones East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Christina Paige, "The ndE of Camelot: An Examination of the Presidency of John F. Kennedy in 1963." (2001). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 114. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/114 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE END OF CAMELOT: AN EXAMINATION OF THE PRESIDENCY OF JOHN F. KENNEDY IN 1963 _______________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History _______________ by Christina Paige Jones May 2001 _______________ Dr. Elwood Watson, Chair Dr. Stephen Fritz Dr. Dale Schmitt Keywords: John F. Kennedy, Civil Rights, Vietnam War ABSTRACT THE END OF CAMELOT: AN EXAMINATION OF THE PRESIDENCY OF JOHN F. KENNEDY IN 1963 by Christina Paige Jones This thesis addresses events and issues that occurred in 1963, how President Kennedy responded to them, and what followed after Kennedy’s assassination. This thesis was created by using books published about Kennedy, articles from magazines, documents, telegrams, speeches, and Internet sources. -

The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense : Robert S. Mcnamara

The Ascendancy of the Secretary ofJULY Defense 2013 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Special Study 4 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Cover Photo: Secretary Robert S. McNamara, Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, and President John F. Kennedy at the White House, January 1963 Source: Robert Knudson/John F. Kennedy Library, used with permission. Cover Design: OSD Graphics, Pentagon. Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Special Study 4 Series Editors Erin R. Mahan, Ph.D. Chief Historian, Office of the Secretary of Defense Jeffrey A. Larsen, Ph.D. President, Larsen Consulting Group Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense July 2013 ii iii Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Contents This study was reviewed for declassification by the appropriate U.S. Government departments and agencies and cleared for release. The study is an official publication of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Foreword..........................................vii but inasmuch as the text has not been considered by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, it must be construed as descriptive only and does Executive Summary...................................ix not constitute the official position of OSD on any subject. Restructuring the National Security Council ................2 Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line in included.