Carsey-Wolf Center at UC Santa Barbara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 18 2012 Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma Hosea H. Harvey Temple University, James E. Beasley School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Hosea H. Harvey, Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma, 18 MICH. J. RACE & L. 1 (2012). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol18/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE, MARKETS, AND HOLLYWOOD'S PERPETUAL ANTITRUST DILEMMA Hosea H. Harvey* This Article focuses on the oft-neglected intersection of racially skewed outcomes and anti-competitive markets. Through historical, contextual, and empirical analysis, the Article describes the state of Hollywood motion-picture distributionfrom its anti- competitive beginnings through the industry's role in creating an anti-competitive, racially divided market at the end of the last century. The Article's evidence suggests that race-based inefficiencies have plagued the film distribution process and such inefficiencies might likely be caused by the anti-competitive structure of the market itself, and not merely by overt or intentional racial-discrimination.After explaining why traditional anti-discrimination laws are ineffective remedies for such inefficiencies, the Article asks whether antitrust remedies and market mechanisms mght provide more robust solutions. -

Las Aportaciones Al Cine De Steven Spielberg Son Múltiples, Pero Sobresale Como Director Y Como Productor

Steven Spielberg Las aportaciones al cine de Steven Spielberg son múltiples, pero sobresale como director y como productor. La labor de un productor de cine puede conllevar cierto control sobre las diversas atribuciones de una película, pero a menudo es poco más que aportar el dinero y los medios que la hacen posible sin entrar mucho en los aspectos creativos de la misma como el guión o la dirección. Es por este motivo que no me voy a detener en la tarea de Spielberg como productor más allá de señalar sus dos productoras de cine y algunas de sus producciones o coproducciones a modo de ejemplo, para complementar el vistazo a la enorme influencia de Spielberg en el mundo cinematográfico: En 1981 creó la productora de cine “Amblin Entertainment” junto con Kathleen Kenndy y Frank Marshall. El logo de esta productora pasaría a ser la famosa silueta de la bicicleta con luna llena de fondo de “ET”, la primera producción de la firma dirigida por Spielberg. Otras películas destacadas con participación de esta productora y no dirigidas por Spielberg son “Gremlins”, “Los Goonies”, “Regreso al futuro”, “Esta casa es una ruina”, “Fievel y el nuevo mundo”, “¿Quién engañó a Roger Rabbit?”, “En busca del Valle Encantado”, “Los picapiedra”, “Casper”, “Men in balck”, “Banderas de nuestros padres” & “Cartas desde Iwo Jima” o las series de televisión “Cuentos asombrosos” y “Urgencias” entre muchas otras películas y series. En 1994 fundaría con Jeffrey Katzenberg y David Geffen la productora y distribuidora DreamWorks, que venderían al estudio Viacom en 2006 tras participar en éxitos como “Shrek”, “American Beauty”, “Náufrago”, “Gladiator” o “Una mente maravillosa”. -

Steven Spielberg's Early Career As a Television Director at Universal Studios

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Surugadai University Academic Information Repository Steven Spielberg's Early Career as a Television Director at Universal Studios 著者名(英) Tomohiro Shimahara journal or 駿河台大学論叢 publication title number 51 page range 47-61 year 2016-01 URL http://doi.org/10.15004/00001463 Steven Spielberg’s Early Career as a Television Director at Universal Studios SHIMAHARA Tomohiro Introduction Steven Spielberg (1946-) is one of the greatest movie directors and producers in the history of motion picture. In his four-decade career, Spielberg has been admired for making blockbusters such as Jaws (1975), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), E.T.: the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Indiana Jones series (1981, 1984, 1989, 2008), Schindler’s List (1993), Jurassic Park series (1993, 1997, 2001, 2015), Saving Private Ryan (1998), Lincoln (2012) and many other smash hits. Spielberg’s life as a filmmaker has been so brilliant that it looks like no one believes that there was any moment he spent at the bottom of the ladder in the movie industry. Much to the surprise of the skeptics, Spielberg was once just another director at Universal Television for the first couple years after launching himself into the cinema making world. Learning how to make good movies by trial and error, Spielberg made a breakthrough with his second feature-length telefilm Duel (1971) at the age of 25 and advanced into the big screen, where he would direct and produce more than 100 movies, including many great hits and some commercial or critical failures, in the next 40-something years. -

Julianne Moore Liam Neeson Amanda Seyfried

JULIANNE MOORE LIAM NEESON AMANDA SEYFRIED in Directed by Atom Egoyan Screenplay by Erin Cressida Wilson CHLOE is fully financed by France‘s StudioCanal and developed by Montecito Picture Company, co-founded by Ivan Reitman and Tom Pollock. Ivan Reitman, Joe Medjuck and Jeffrey Clifford are producers for Montecito. Co-producers are Simone Urdl and Jennifer Weiss. Executive Producers are Tom Pollock along with Jason Reitman, Daniel Dubiecki, and Ron Halpern. CHLOE will be distributed by StudioCanal in France and in the United Kingdom and Germany through its subsidiaries Optimum Releasing and Kinowelt. It will also handle worldwide sales outside its direct distribution territories. The Cast Catherine Stewart JULIANNE MOORE David Stewart LIAM NEESON Chloe AMANDA SEYFRIED Michael Stewart MAX THIERIOT Frank R.H. THOMSON Anna NINA DOBREV Receptionist MISHU VELLANI Bimsy JULIE KHANER Alicia LAURA DE CARTERET Eliza NATALIE LISINSKA Trina TIFFANY KNIGHT Miranda MEGHAN HEFFERN Party Guest ARLENE DUNCAN Another Girl KATHY MALONEY Maria ROSALBA MARTINNI Waitress TAMSEN McDONOUGH Waitress 2 KATHRYN KRIITMAA Bartender ADAM WAXMAN Young Co-Ed KRYSTA CARTER Nurse SEVERN THOMPSON ‗Orals‘ Student SARAH CASSELMAN Boy DAVID REALE Boy 2 MILTON BARNES Woman Behind Bar KYLA TINGLEY Chloe‘s Client #1 SEAN ORR Chloe‘s Client #2 PAUL ESSIEMBRE Chloe‘s Client #3 ROD WILSON Stunt Hockey Player RILEY JONES • CHLOE 2 The Filmmakers Director ATOM EGOYAN Writer ERIN CRESSIDA WILSON Produced by IVAN REITMAN Producers JOE MEDJUCK JEFFREY CLIFFORD Co-Producers SIMONE URDL JENNIFER WEISS Executive Producers JASON REITMAN DANIEL DUBIECKI THOMAS P. POLLOCK RON HALPERN Associate Producers ALI BELL ERIN CRESSIDA WILSON Production Manager STEPHEN TRAYNOR Director of Photography PAUL SAROSSY Production Designer PHILLIP BARKER Editor SUSAN SHIPTON Music MYCHAEL DANNA Costumes DEBRA HANSON Casting JOANNA COLBERT (US) RICHARD MENTO (US) JOHN BUCHAN (Canada) JASON KNIGHT (Canada) Camera Operator PAUL SAROSSY First Assistant Director DANIEL J. -

Al Cinema Dal 12 Marzo

Presenta CHLOE Diretto da ATOM EGOYAN Sceneggiatura di ERIC CRESSIDA WILSON Con JULIANNE MOORE LIAM NEESON AMANDA SEYFRIED I materiali sono scaricabili dall’ area stampa di www.eaglepictures.com Visita anche www.chloeilfilm.it Durata 96’ AL CINEMA DAL 12 MARZO Ufficio Stampa: Marianna Giorgi [email protected] Cast Artistico Catherine Stewart JULIANNE MOORE David Stewart LIAM NEESON Chloe AMANDA SEYFRIED Michael Stewart MAX THIERIOT Frank R.H. THOMSON Anna NINA DOBREV Reception MISHU VELLANI Bimsy JULIE KHANER Alicia LAURA DE CARTERET Eliza NATALIE LISINSKA Trina TIFFANY KNIGHT Miranda MEGHAN HEFFERN Ospite festa ARLENE DUNCAN Altra ragazza KATHY MALONEY Maria ROSALBA MARTINNI Cameriera TAMSEN McDONOUGH Cameriera 2 KATHRYN KRIITMAA Barman ADAM WAXMAN Giovane Co-Ed KRYSTA CARTER Infermiere SEVERN THOMPSON Studente Oral SARAH CASSELMAN Ragazzo DAVID REALE Ragazzo 2 MILTON BARNES Donna barista KYLA TINGLEY Cliente Chloe SEAN ORR Cliente Chloe2 PAUL ESSIEMBRE Cliente Chloe 3 ROD WILSON Stunt Giocatore Hockey RILEY JONES Cast Tecnico Regista ATOM EGOYAN Sceneggiatore ERIN CRESSIDA WILSON Prodotto da IVAN REITMAN Produttori JOE MEDJUCK JEFFREY CLIFFORD Co-produttuori SIMONE URDL JENNIFER WEISS Produttori esecutivi JASON REITMAN DANIEL DUBIECKI THOMAS P. POLLOCK RON HALPERN Produttori associati ALI BELL ERIN CRESSIDA WILSON Direttore di produzione STEPHEN TRAYNOR Direttore della fotografia PAUL SAROSSY Scenografo PHILLIP BARKER Montatore SUSAN SHIPTON Musiche MYCHAEL DANNA Costumi DEBRA HANSON Casting JOANNA COLBERT (US) RICHARD MENTO (US) JOHN BUCHAN (Canada) JASON KNIGHT (Canada) Operatore PAUL SAROSSY Primo aiuto regista DANIEL J. MURPHY Suono BISSA SCEKIC Supervisore sceneggiatura JILL CARTER Attrezzista CRAIG GRANT Elettricista BOB DAVIDSON Macchinista CHRIS FAULKNER Location Manager EARDLEY WILMOT Breve sinossi CHLOE è una storia di amore, di suspense e tradimenti. -

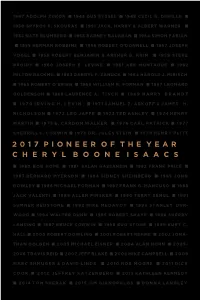

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner. -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Atom Egoyan Julianne Moore, Liam Neeson, Amanda

TORONTO 2009 Offizielle Selektion CHLOE Ein Film von Atom Egoyan Mit Julianne Moore, Liam Neeson, Amanda Seyfried, Max Thieriot, Meghan Heffern Dauer: 96 min. Kinostart: 13.05.2010 Download Fotos : www.frenetic.ch/presse Pressearbeit VERLEIH Susanne Hefti FRENETIC FILMS prochaine ag Bachstrasse 9 • 8038 Zürich Tel. 044 488 44 25 Tél. 044 488 44 00 • Fax 044 488 44 11 [email protected] [email protected] • www.frenetic.ch SYNOPSIS In die gut funktionierende Ehe der erfolgreichen Ärztin Catherine (Julianne Moore) und des beliebten Musikprofessor David (Liam Neeson) platzt eine verräterische SMS: Hat David eine Affäre? Um seine Treue zu testen, engagiert Catherine das Luxus-Callgirl Chloe (Amanda Seyfried). Die aufregende junge Frau präsentiert ihrer Auftraggeberin schnell erste erotische Ergebnisse. Catherine ist schockiert und möchte das Geschäft beenden, aber sie erliegt der Faszination eines gefährlichen Spieles, bei dem sie mehr und mehr die Kontrolle verliert… Cast Catherine .............................................................................JULIANNE MOORE David ........................................................................................... LIAM NEESON Chloe ................................................................................. AMANDA SEYFRIED Michael ....................................................................................... MAX THIERIOT Frank ......................................................................................R. H. THOMPSON Anna ............................................................................................NINA -

Ltc-042-2018-News-Article-Vanity-Fair

From Coast to Toast At opposite ends of the country, two of America’s most golden coastal enclaves are waging the same desperate battle against erosion. With beaches and bluffs in both Malibu and Nantucket disappearing into the ocean, wealthy homeowners are prepared to do almost anything—spend tens of millions on new sand, berms, retaining walls, and other measures—to save their precious waterfront properties. What’s stopping them? William D. Cohan and Vanessa Grigoriadis report on the clash between deep-pocketed summer people and local working folks. by VANESSA GRIGORIADIS AUGUST 2013 SAND CASTLES Left, The coastline of Broad Beach, in Malibu, with a stone seawall protecting the houses. Right, Houses perched on the edge of Sconset Bluff, on Nantucket, Massachusetts., Left, Photograph by Mark Holtzman; right, By George Riethof. arlier this summer, on what passed for a clear morning in Los Angeles, Tom Ford, director of marine programs at the Santa MonicaJe Baynni fRestorationer Lawren Foundation,ce Is went to the SantaPho tMonicaos: EMunicipal AirportPer tofe ccatchtly F ain ridee w upith the Pacific coast in a BeechcraftPhotos: Bonanza G36. (CladThos ine Ba rplaidad P shirtitt D aandtin gchinos, he seemed notVa toni tbey Fair’s related to the designer.)BY ERIKA HA “WhatRWOOD a totally sweet glass cockpit,”B Yhe VA toldNITY FtheAIR pilot, who was donating this flight through LightHawk, a nonprofit group dedicated to helping environmentalists document problems from the air. As Santa Monica drifted by below, its famous boardwalk and Ferris wheel appearing as though they were little pieces on a game board, the minuscule Bonanza headed toward the great blue ocean, which was gently undulating like a fresh duvet being fluffed on a bed. -

Steven Spielberg Scrive E Dirige Il Suo Primo Lungometraggio Amatoriale, Firelight (1964), Che Sarà Proiettato in Un Cinema Cittadino

ESORDI DI UNA CARRIERA MOLTO PROMETTENTE • Dopo vari mediometraggi, appartenenti ai generi più disparati (western, noir, avventura), il diciassettenne Steven Spielberg scrive e dirige il suo primo lungometraggio amatoriale, Firelight (1964), che sarà proiettato in un cinema cittadino. Il budget del film è di 500 dollari . • Qui, per la prima volta, Spielberg si confronta con il genere della fantascienza . Il tema di Firelight sarà ampiamente ripreso e approfondito nel successivo Incontri ravvicinati del terzo tipo (Close Encounters of the Third Kind , 1977 ). • È lo stesso Spielberg a comporre la colonna sonora di Firelight , con il suo clarinetto, mentre la madre, Leah , un tempo promettente pianista, aggiunge un brano al piano. La Arcadia High School , la scuola pubblica frequentata da Steven e dalle sorelle a Phoenix , ha poi ricreato l’intera colonna sonora. • Il film è realizzato durante i week-end . Molte scene saranno girate a casa di Spielberg e nel suo garage. • Nel cast, compare anche la sorella del futuro regista, Nancy Spielberg. Oggi, Firelight è purtroppo considerato un film perduto. • O meglio, ci sono rimasti soltanto alcuni frammenti dell’intera pellicola. Tali estratti testimoniano già un precoce, seppure ancora grossolano, talento visivo da parte dell’esordiente regista . Firelight (1964) • Il giovane Spielberg attende l’inizio della premiere del suo primo lungometraggio . • Circa 500 persone assisteranno alla prima del film. Il costo del biglietto sarà di un dollaro. Alcune immagini dal film… • Durante il periodo trascorso in Arizona a causa del lavoro di Arnold, l’unione tra i coniugi Spielberg si deteriora . In un tentativo di salvare il matrimonio dal naufragio, la famiglia decide di trasferirsi a Saratoga, in California . -

John Cassavetes

Cassavetes on Cassavetes Ray Carney is Professor of Film and American Studies and Director of the undergraduate and graduate Film Studies programs at Boston Uni- versity. He is the author or editor of more than ten books, including the critically acclaimed John Cassavetes: The Adventure of Insecurity; The Films of Mike Leigh: Embracing the World; The Films of John Cas- savetes: Pragmatism, Modernism, and the Movies; American Vision: The Films of Frank Capra; Speaking the Language of Desire: The Films of Carl Dreyer; American Dreaming; and the BFI monograph on Cas- savetes’ Shadows. He is an acknowledged expert on William James and pragmatic philosophy, having contributed major essays on pragmatist aesthetics to Morris Dickstein’s The Revival of Pragmatism: New Essays on Social Thought, Law, and Culture and Townsend Ludington’s A Modern Mosaic: Art and Modernism in the United States. He co- curated the Beat Culture and the New America show for the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, is General Editor of the Cam- bridge Film Classics series, and is a frequent speaker at film festivals around the world. He is regarded as one of the world’s leading authori- ties on independent film and American art and culture, and has a web site with more information at www.Cassavetes.com. in the same series woody allen on woody allen edited by Stig Björkman almodóvar on almodóvar edited by Frédéric Strauss burton on burton edited by Mark Salisbury cronenberg on cronenberg edited by Chris Rodley de toth on de toth edited by Anthony Slide fellini on -

Music Genres and Corporate Cultures

Music Genres and Corporate Cultures Music Genres and Corporate Cultures explores the workings of the music industry, tracing the often uneasy relationship between entertainment cor- porations and the artists they sign. Keith Negus examines the contrasting strategies of major labels like Sony and Universal in managing different genres, artists and staff, and assesses the various myths of corporate cul- ture. How do takeovers affect the treatment of artists? Why was Poly- Gram perceived as too European to attract US artists? Why and how did EMI Records attempt to change their corporate culture? Through a study of three major genres—rap, country and salsa—Negus investigates why the music industry recognises and rewards certain sounds, and how this influences both the creativity of musicians and their audiences. He explores why some artists get international promotion while others are neglected, and how performers are packaged as ‘world music’. Negus examines the tension between rap’s image as a spontaneous ‘music of the streets’ and the practicalities of the market, asks why execu- tives from New York feel uncomfortable when they visit the country music business in Nashville, and explains why the lack of soundscan sys- tems in Puerto Rican record shops affects salsa’s position on the US Bill- board chart. Drawing on extensive research and interviews with music industry per- sonnel in Britain, the United States and Japan, Music Genres and Corpo- rate Cultures shows how the creation, circulation and consumption of popular music is shaped by record companies and corporate business style while stressing that music production takes place within a broader cul- ture, not totally within the control of large corporations.