Neoliberalism and Monopoly in the Motion Picture Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Impact of the Recorded Music Industry in India September 2019

Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India September 2019 Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India Contents Foreword by IMI 04 Foreword by Deloitte India 05 Glossary 06 Executive summary 08 Indian recorded music industry: Size and growth 11 Indian music’s place in the world: Punching below its weight 13 An introduction to economic impact: The amplification effect 14 Indian recorded music industry: First order impact 17 “Formal” partner industries: Powered by music 18 TV broadcasting 18 FM radio 20 Live events 21 Films 22 Audio streaming OTT 24 Summary of impact at formal partner industries 25 Informal usage of music: The invisible hand 26 A peek into brass bands 27 Typical brass band structure 28 Revenue model 28 A glimpse into the lives of band members 30 Challenges faced by brass bands 31 Deep connection with music 31 Impact beyond the numbers: Counts, but cannot be counted 32 Challenges faced by the industry: Hurdles to growth 35 Way forward: Laying the foundation for growth 40 Conclusive remarks: Unlocking the amplification effect of music 45 Acknowledgements 48 03 Economic impact of the recorded music industry in India Foreword by IMI CIRCA 2019: the story of the recorded Nusrat Fateh Ali-Khan, Noor Jehan, Abida “I know you may not music industry would be that of David Parveen, Runa Laila, and, of course, the powering Goliath. The supercharged INR iconic Radio Ceylon. Shifts in technology neglect me, but it may 1,068 crore recorded music industry in and outdated legislation have meant be too late by the time India provides high-octane: that the recorded music industries in a. -

Tuning Into the On-Demand Streaming Culture—Hollywood Guilds’ Evolution Imperative in Today’S Media Landscape

UCLA UCLA Entertainment Law Review Title Tuning Into the On-Demand Streaming Culture—Hollywood Guilds’ Evolution Imperative in Today’s Media Landscape Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2152q2t4 Journal UCLA Entertainment Law Review, 27(1) ISSN 1073-2896 Author Roth, Blaine Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.5070/LR8271048856 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California TUNING INTO THE ON-DEMAND STREAMING CULTURE— Hollywood Guilds’ Evolution Imperative in Today’s Media Landscape Blaine Roth Abstract Hollywood television and film production has largely been unionized since the early 1930s. Today, due in part to technological advances, the industry is much more expansive than it has ever been, yet the Hollywood unions, known as “guilds,” have arguably not evolved at a similar pace. Although the guilds have adapted to the needs of their members in many aspects, have they suc- cessfully adapted to the evolving Hollywood business model? This Comment puts a focus on the Writers Guild of America, Directors Guild of America, and the Screen Actors Guild, known as SAG-AFTRA following its merger in 2012, and asks whether their respective collective bargaining agreements are out-of- step with the evolution of the industry over the past ten years, particularly in the areas of new media and the direct-to-consumer model. While analyzing the guilds in the context of the industry environment as it is today, this Com- ment contends that as the guilds continue to feel more pronounced effects from the evolving media landscape, they will need to adapt at a much more rapid pace than ever before in order to meet the needs of their members. -

9780367508234 Text.Pdf

Development of the Global Film Industry The global film industry has witnessed significant transformations in the past few years. Regions outside the USA have begun to prosper while non-traditional produc- tion companies such as Netflix have assumed a larger market share and online movies adapted from literature have continued to gain in popularity. How have these trends shaped the global film industry? This book answers this question by analyzing an increasingly globalized business through a global lens. Development of the Global Film Industry examines the recent history and current state of the business in all parts of the world. While many existing studies focus on the internal workings of the industry, such as production, distribution and screening, this study takes a “big picture” view, encompassing the transnational integration of the cultural and entertainment industry as a whole, and pays more attention to the coordinated develop- ment of the film industry in the light of influence from literature, television, animation, games and other sectors. This volume is a critical reference for students, scholars and the public to help them understand the major trends facing the global film industry in today’s world. Qiao Li is Associate Professor at Taylor’s University, Selangor, Malaysia, and Visiting Professor at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne. He has a PhD in Film Studies from the University of Gloucestershire, UK, with expertise in Chinese- language cinema. He is a PhD supervisor, a film festival jury member, and an enthusiast of digital filmmaking with award- winning short films. He is the editor ofMigration and Memory: Arts and Cinemas of the Chinese Diaspora (Maison des Sciences et de l’Homme du Pacifique, 2019). -

Media Ownership Chart

In 1983, 50 corporations controlled the vast majority of all news media in the U.S. At the time, Ben Bagdikian was called "alarmist" for pointing this out in his book, The Media Monopoly . In his 4th edition, published in 1992, he wrote "in the U.S., fewer than two dozen of these extraordinary creatures own and operate 90% of the mass media" -- controlling almost all of America's newspapers, magazines, TV and radio stations, books, records, movies, videos, wire services and photo agencies. He predicted then that eventually this number would fall to about half a dozen companies. This was greeted with skepticism at the time. When the 6th edition of The Media Monopoly was published in 2000, the number had fallen to six. Since then, there have been more mergers and the scope has expanded to include new media like the Internet market. More than 1 in 4 Internet users in the U.S. now log in with AOL Time-Warner, the world's largest media corporation. In 2004, Bagdikian's revised and expanded book, The New Media Monopoly , shows that only 5 huge corporations -- Time Warner, Disney, Murdoch's News Corporation, Bertelsmann of Germany, and Viacom (formerly CBS) -- now control most of the media industry in the U.S. General Electric's NBC is a close sixth. Who Controls the Media? Parent General Electric Time Warner The Walt Viacom News Company Disney Co. Corporation $100.5 billion $26.8 billion $18.9 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues $23 billion 1998 revenues $13 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues Background GE/NBC's ranks No. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Co-Optation of the American Dream: a History of the Failed Independent Experiment

Cinesthesia Volume 10 Issue 1 Dynamics of Power: Corruption, Co- Article 3 optation, and the Collective December 2019 Co-optation of the American Dream: A History of the Failed Independent Experiment Kyle Macciomei Grand Valley State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine Recommended Citation Macciomei, Kyle (2019) "Co-optation of the American Dream: A History of the Failed Independent Experiment," Cinesthesia: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine/vol10/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cinesthesia by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Macciomei: Co-optation of the American Dream Independent cinema has been an aspect of the American film industry since the inception of the art form itself. The aspects and perceptions of independent film have altered drastically over the years, but in general it can be used to describe American films produced and distributed outside of the Hollywood major studio system. But as American film history has revealed time and time again, independent studios always struggle to maintain their freedom from the Hollywood industrial complex. American independent cinema has been heavily integrated with major Hollywood studios who have attempted to tap into the niche markets present in filmgoers searching for theatrical experiences outside of the mainstream. From this, we can say that the American independent film industry has a long history of co-optation, acquisition, and the stifling of competition from the major film studios present in Hollywood, all of whom pose a threat to the autonomy that is sought after in these markets by filmmakers and film audiences. -

Download-To-Own and Online Rental) and Then to Subscription Television And, Finally, a Screening on Broadcast Television

Exporting Canadian Feature Films in Global Markets TRENDS, OPPORTUNITIES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS MARIA DE ROSA | MARILYN BURGESS COMMUNICATIONS MDR (A DIVISION OF NORIBCO INC.) APRIL 2017 PRODUCED WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF 1 EXPORTING CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS IN GLOBAL MARKETS Acknowledgements This study was commissioned by the Canadian Media Producers Association (CMPA), in partnership with the Association québécoise de la production médiatique (AQPM), the Cana- da Media Fund (CMF), and Telefilm Canada. The following report solely reflects the views of the authors. Findings, conclusions or recom- mendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders of this report, who are in no way bound by any recommendations con- tained herein. 2 EXPORTING CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS IN GLOBAL MARKETS Executive Summary Goals of the Study The goals of this study were three-fold: 1. To identify key trends in international sales of feature films generally and Canadian independent feature films specifically; 2. To provide intelligence on challenges and opportunities to increase foreign sales; 3. To identify policies, programs and initiatives to support foreign sales in other jurisdic- tions and make recommendations to ensure that Canadian initiatives are competitive. For the purpose of this study, Canadian film exports were defined as sales of rights. These included pre-sales, sold in advance of the completion of films and often used to finance pro- duction, and sales of rights to completed feature films. In other jurisdictions foreign sales are being measured in a number of ways, including the number of box office admissions, box of- fice revenues, and sales of rights. -

Unemployment in an Extended Cournot Oligopoly Model∗

Unemployment in an Extended Cournot Oligopoly Model∗ Claude d'Aspremont,y Rodolphe Dos Santos Ferreiraz and Louis-Andr´eG´erard-Varetx 1 Introduction Attempts to explain unemployment1 begin with the labour market. Yet, by attributing it to deficient demand for goods, Keynes questioned the use of partial analysis, and stressed the need to consider interactions between the labour and product markets. Imperfect competition in the labour market, reflecting union power, has been a favoured explanation; but imperfect competition may also affect employment through producers' oligopolistic behaviour. This again points to a general equilibrium approach such as that by Negishi (1961, 1979). Here we propose an extension of the Cournot oligopoly model (unlike that of Gabszewicz and Vial (1972), where labour does not appear), which takes full account of the interdependence between the labour market and any product market. Our extension shares some features with both Negishi's conjectural approach to demand curves, and macroeconomic non-Walrasian equi- ∗Reprinted from Oxford Economic Papers, 41, 490-505, 1989. We thank P. Champsaur, P. Dehez, J.H. Dr`ezeand J.-J. Laffont for helpful comments. We owe P. Dehez the idea of a light strengthening of the results on involuntary unemployment given in a related paper (CORE D.P. 8408): see Dehez (1985), where the case of monopoly is studied. Acknowledgements are also due to Peter Sinclair and the Referees for valuable suggestions. This work is part of the program \Micro-d´ecisionset politique ´economique"of Commissariat G´en´eral au Plan. Financial support of Commissariat G´en´eralau Plan is gratefully acknowledged. -

Paramount Consent Decree Review Public Comments 2018

COMMENTS OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF THEATRE OWNERS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, ANTITRUST DIVISION REVIEW OF PARAMOUNT CONSENT DECREES October 1, 2018 National Association of Theatre Owners 1705 N Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 962-0054 I. INTRODUCTION The National Association of Theatre Owners (“NATO”) respectfully submits the following comments in response to the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division’s (the “Department”) announced intentions to review the Paramount Consent Decrees (the “Decrees”). Individual motion picture theater companies may comment on the five various provisions of the Decrees but NATO’s comment will focus on one seminal provision of the Decrees. Specifically, NATO urges the Department to maintain the prohibition on block booking, as that prohibition undoubtedly continues to support pro-competitive practices. NATO is the largest motion picture exhibition trade organization in the world, representing more than 33,000 movie screens in all 50 states, and additional cinemas in 96 countries worldwide. Our membership includes the largest cinema chains in the world and hundreds of independent theater owners. NATO and its members have a significant interest in preserving an open marketplace in the North American film industry. North America remains the biggest film-going market in the world: It accounts for roughly 30% of global revenue from only 5% of the global population. The strength of the American movie industry depends on the availability of a wide assortment of films catering to the varied tastes of moviegoers. Indeed, both global blockbusters and low- budget independent fare are necessary to the financial vitality and reputation of the American film industry. -

Chapter 16 Oligopoly and Game Theory Oligopoly Oligopoly

Chapter 16 “Game theory is the study of how people Oligopoly behave in strategic situations. By ‘strategic’ we mean a situation in which each person, when deciding what actions to take, must and consider how others might respond to that action.” Game Theory Oligopoly Oligopoly • “Oligopoly is a market structure in which only a few • “Figuring out the environment” when there are sellers offer similar or identical products.” rival firms in your market, means guessing (or • As we saw last time, oligopoly differs from the two ‘ideal’ inferring) what the rivals are doing and then cases, perfect competition and monopoly. choosing a “best response” • In the ‘ideal’ cases, the firm just has to figure out the environment (prices for the perfectly competitive firm, • This means that firms in oligopoly markets are demand curve for the monopolist) and select output to playing a ‘game’ against each other. maximize profits • To understand how they might act, we need to • An oligopolist, on the other hand, also has to figure out the understand how players play games. environment before computing the best output. • This is the role of Game Theory. Some Concepts We Will Use Strategies • Strategies • Strategies are the choices that a player is allowed • Payoffs to make. • Sequential Games •Examples: • Simultaneous Games – In game trees (sequential games), the players choose paths or branches from roots or nodes. • Best Responses – In matrix games players choose rows or columns • Equilibrium – In market games, players choose prices, or quantities, • Dominated strategies or R and D levels. • Dominant Strategies. – In Blackjack, players choose whether to stay or draw. -

Newsletter Volume 19 / No

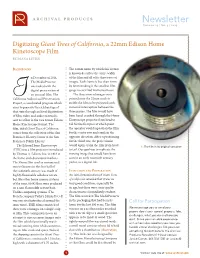

Newsletter Volume 19 / No. 3 / 2015 Digitizing Giant Trees of California, a 22mm Edison Home Kinetoscope Film BY DIANA LITTLE BACKGROUND The 22mm name by which this format is known describes the entire width n December of 2014, of the film and all of its three rows of The MediaPreserve images. Each frame is less than 4mm was tasked with the by 6mm making it the smallest film digital preservation of gauge to ever find mainstream use. an unusual film. The The three rows of images were ICalifornia Audiovisual Preservation printed onto the 22mm stock to Project, a coordinated program which enable the film to be projected with aims to preserve the rich heritage of minimal interruption between the that state through archival digitization three passes. The film would have of film, video and audio materials, been hand-cranked through the Home sent us a film in the rare 22mm Edison Kinetoscope projector from head to Home Kinetoscope format. The tail for the first pass at which point film, titled Giant Trees of California, the operator would reposition the film comes from the collection of the San for the center row and crank in the Francisco History Center at the San opposite direction. After repositioning Francisco Public Library. for the third row, the projectionist The Edison Home Kinetoscope would again crank the film from head 1: The film in its original container (EHK) was a film projector introduced to tail. Our goal was to replicate the by Thomas A. Edison, Inc. in 1912 to moving image that would have been the home and educational markets. -

Visions of Electric Media Electric of Visions

TELEVISUAL CULTURE Roberts Visions of Electric Media Ivy Roberts Visions of Electric Media Television in the Victorian and Machine Ages Visions of Electric Media Televisual Culture Televisual culture encompasses and crosses all aspects of television – past, current and future – from its experiential dimensions to its aesthetic strategies, from its technological developments to its crossmedial extensions. The ‘televisual’ names a condition of transformation that is altering the coordinates through which we understand, theorize, intervene, and challenge contemporary media culture. Shifts in production practices, consumption circuits, technologies of distribution and access, and the aesthetic qualities of televisual texts foreground the dynamic place of television in the contemporary media landscape. They demand that we revisit concepts such as liveness, media event, audiences and broadcasting, but also that we theorize new concepts to meet the rapidly changing conditions of the televisual. The series aims at seriously analyzing both the contemporary specificity of the televisual and the challenges uncovered by new developments in technology and theory in an age in which digitization and convergence are redrawing the boundaries of media. Series editors Sudeep Dasgupta, Joke Hermes, Misha Kavka, Jaap Kooijman, Markus Stauff Visions of Electric Media Television in the Victorian and Machine Ages Ivy Roberts Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: ‘Professor Goaheadison’s Latest,’ Fun, 3 July 1889, 6. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden