Co-Optation of the American Dream: a History of the Failed Independent Experiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Designation Lpb 559/08

REPORT ON DESIGNATION LPB 559/08 Name and Address of Property: MGM Building 2331 Second Avenue Legal Description: Lot 7 of Supplemental Plat to Block 27 to Bell and Denny’s First Addition to the City of Seattle, according to the plat thereof recorded in Volume 2 of Plats, Page 83, in King County, Washington; Except the northeasterly 12 feet thereof condemned for widening 2nd Avenue. At the public meeting held on October 1, 2008, the City of Seattle's Landmarks Preservation Board voted to approve designation of the MGM Building at 2331 Second Avenue, as a Seattle Landmark based upon satisfaction of the following standard for designation of SMC 25.12.350: C. It is associated in a significant way with a significant aspect of the cultural, political, or economic heritage of the community, City, state or nation; and D. It embodies the distinctive visible characteristics of an architectural style, period, or of a method of construction. STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE This building is notable both for its high degree of integrity and for its Art Deco style combining dramatic black terra cotta and yellowish brick. It is also one of the very few intact elements remaining on Seattle’s Film Row, a significant part of the Northwest’s economic and recreational life for nearly forty years. Neighborhood Context: The Development of Belltown Belltown may have seen more extensive changes than any other Seattle neighborhood, as most of its first incarnation was washed away in the early 20th century. The area now known as Belltown lies on the donation claim of William and Sarah Bell, who arrived with the Denny party at Alki Beach on November 13, 1851. -

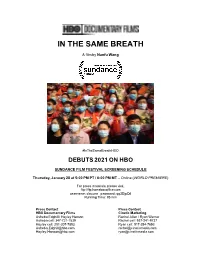

In the Same Breath

IN THE SAME BREATH A film by Nanfu Wang #InTheSameBreathHBO DEBUTS 2021 ON HBO SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL SCREENING SCHEDULE Thursday, January 28 at 5:00 PM PT / 6:00 PM MT – Online (WORLD PREMIERE) For press materials, please visit: ftp://ftp.homeboxoffice.com username: documr password: qq3DjpQ4 Running Time: 95 min Press Contact Press Contact HBO Documentary Films Cinetic Marketing Asheba Edghill / Hayley Hanson Rachel Allen / Ryan Werner Asheba cell: 347-721-1539 Rachel cell: 937-241-9737 Hayley cell: 201-207-7853 Ryan cell: 917-254-7653 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] LOGLINE Nanfu Wang's deeply personal IN THE SAME BREATH recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. SHORT SYNOPSIS IN THE SAME BREATH, directed by Nanfu Wang (“One Child Nation”), recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. In a deeply personal approach, Wang, who was born in China and now lives in the United States, explores the parallel campaigns of misinformation waged by leadership and the devastating impact on citizens of both countries. Emotional first-hand accounts and startling, on-the-ground footage weave a revelatory picture of cover-ups and misinformation while also highlighting the strength and resilience of the healthcare workers, activists and family members who risked everything to communicate the truth. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT I spent a lot of my childhood in hospitals taking care of my father, who had rheumatic heart disease. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

Female Investors Make a Bid for the Weinstein Company

Case Study Female Investors Make a Bid for The Weinstein Company Thought Leadership and Advocacy PR The Challenge: After disgraced movie producer Harvey Weinstein was ousted from his company, Maria Contreras- Sweet, a former cabinet official and head of the Small Business Administration under President Barack Obama, assembled a majority-female team of Hollywood heavyweights to make a bid for The Weinstein Company and rebrand it as a place that was welcoming to, and supportive of, women. TASC was brought on to generate excitement around the deal and cultivate support for it. Our Strategy: TASC capitalized on the momentum of the Time’s Up and #MeToo movements, and made Contreras- Sweet and her team a symbol of hope and progress in the film industry’s treatment of women. TASC managed a huge volume of media requests for Contreras-Sweet and strategically released information on the deal to garner community interest and support from key decision makers. Several other groups were also in the running to secure a deal, and many details of negotiations could not be made public. TASC worked to ensure that outlets were accurately reporting on the details of Contreras-Sweet’s deal, the only one to save jobs, create a female-majority board of directors and create a $90 million compensation fund for Weinstein’s victims. Results: Our work generated hundreds of media placements in national outlets including Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, The New York Times, ABC News, CNBC, Yahoo! Finance, CNN Money, The Los Angeles Times, The Wall Street Journal, Refinery29 and dozens more, which turned the tide in Contreras-Sweet’s favor with The Weinstein Company’s board of directors. -

Kerkorian Slashes His GM Stake to Less Than 5%

Kerkorian slashes his GM stake to less than 5% By Sharon Silke Carty, USA TODAY December 1, 2006 DETROIT — Billionaire investor Kirk Kerkorian will shed an additional 14 million shares of General Motors stock further indicating that he's no longer interested in pressuring GM's management for change. Analysts are divided over whether Kerkorian acted as an agent of change for the ailing automaker or whether he was just a distraction. During his year and a half as a major GM shareholder, he managed to get his top lieutenant, Jerry York, named to the board and pressured the automaker to explore an alliance with Nissan and Renault. Every major stock sale or buy made by Kerkorian has made headlines. After Thursday's sale, he will own less than 5% of GM and will no longer be required to file statements with the Securities and Exchange Commission regarding his shares. The Wall Street Journal, citing a person familiar with the matter, reported in Friday's edition that the billionaire investor sold his entire remaining investment in GM — 28 million shares — at $29.95 a share, a transaction worth more than $800 million. The newspaper reported that the shares were sold to Bank of America, a key lender to Kerkorian.. Merrill Lynch analyst John Murphy noted that there was a 28 million share block trade in GM stock on the New York Stock Exchange shortly after the filing Thursday. "It appears that Kerkorian may now be out of his entire GM position," Murphy wrote in a research note. Carrie Bloom, spokeswoman for Kerkorian's Tracinda Corp., said she could not comment on the transaction beyond the SEC filing. -

Good Food ... Good Feelings • Shirley (Neon) — Elisabeth Moss, Logan Lerman, Michael Stuhlbarg

Jay’s Pix Presents at the International improvisational style with a cast of non-actors. Museum — Film historian Jay Duncan and the Fountain Theatre — 2469 Calle de Sunset Film Society host presentations at 2 Guadalupe, 1/2 block south of the plaza in p.m. Saturdays at International Museum of Art, Mesilla. Theatre closed at least through April 3; 1211 Montana (door on Brown opens at 1:30 check website for updates and reopening p.m.). Admission is free. Snacks available for schedule. purchase; guests encouraged to come early for directed and co-written by Billy Wilder. Two Miami — which also happens to be the destina- The historic theater, operated by the Mesilla special attractions. Information: 543-6747 musicians in 1929 Chicago (Jack Lemmon and tion for the mobsters attending a convention. Valley Film Society, features films at 7:30 p.m. (museum), internationalmuseumofart.net and Tony Curtis) accidentally witness the St. • April 18: “Chicago.” The 2002 musical crime nightly, plus 1:30 p.m. Saturday and 2:30 p.m. sunsetfilmsociety.org. Valentine’s Day massacre and go on the lam, comedy-drama film, based on the stage musi- Sunday. Some 7:30 p.m. Sunday night screen- This month’s films Celebrate the Roarin’ 20s. hiding from the mobsters who saw them. Since cal, explores the themes of celebrity, scandal ings have an open caption option. Admission: • April 11 : “Some Like It Hot.” Voted the jobs are scarce during the Great Depression, and corruption in Chicago during the Jazz Age. $8 ($7 matinees, seniors, military and students No. -

American University of Armenia the Impact Of

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF ARMENIA THE IMPACT OF DIASPORA AND DUAL CITIZENSHIP POLICY ON THE STATECRAFT PROCESS IN THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA A MASTER’S ESSAY SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS FOR PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY ARLETTE AVAKIAN YEREVAN, ARMENIA May 2008 SIGNATURE PAGE ___________________________________________________________________________ Faculty Advisor Date ___________________________________________________________________________ Dean Date AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF ARMENIA May 2008 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The work on my Master’s Essay was empowered and facilitated by the effort of several people. I would like to express my deep gratitude to my faculty adviser Mr. Vigen Sargsyan for his professional approach in advising and revising this Master’s Essay during the whole process of its development. Mr. Sargsyan’s high professional and human qualities were accompanying me along this way and helping me to finish the work I had undertaken. My special respect and appreciation to Dr. Lucig Danielian, Dean of School of Political Science and International Affairs, who had enormous impact on my professional development as a graduate student of AUA. I would like to thank all those organizations, political parties and individuals whom I benefited considerably. They greatly provided me with the information imperative for the realization of the goals of the study. Among them are the ROA Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Armenian Assembly of America Armenia Headquarter, Head Office of the Hay Dat (Armenian Cause) especially fruitful interview with the International Secretariat of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation Bureau in Yerevan, Tufenkian Foundation, Mr. Ralph Yirikyan, the General Manager of Viva Cell Company, Mr. -

Independent Experimental Film (Animation and Live-Action) Remains the Great Hardly-Addressed Problem of Film Preservation

RESTORING EXPERIMENTAL FILMS by William Moritz (From Anthology Film Archives' "Film Preservation Honors" program, 1997) Independent experimental film (animation and live-action) remains the great hardly-addressed problem of film preservation. While million-dollar budgets digitally remaster commercial features, and telethon campaigns raise additional funds from public donations to restore "classic" features, and most of the film museums and archives spend their meager budgets on salvaging nitrates of early live-action and cartoon films, thousands of experimental films languish in desperate condition. To be honest, experimental film is little known to the general public, so a telethon might not engender the nostalgia gifts that pour in to the American Movie Classics channel. But at their best, experimental films constitute Art of the highest order, and, like the paintings and sculptures and prints and frescos of previous centuries, merit preservation, since they will be treasured continuingly and increasingly by scholars, connoisseurs, and thankful popular audiences of future generations - for the Botticellis and Rembrandts and Vermeers and Turners and Monets and Van Goghs of our era will be found among the experimental filmmakers. Experimental films pose many special problems that account for some of this neglect. Independent production often means that the "owner" of legal rights to the film may be in question, so the time and money spent on a restoration may be lost when a putative owner surfaces to claim the restored product. Because the style of an experimental film may be eccentric in the extreme, it can be hard to determine its original state: is this print complete? Have colors changed? was there a sound accompaniment? what was the speed or configuration of projection? etc. -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Glenn-Garland-Editor-Credits.Pdf

GLENN GARLAND, ACE Editor Television PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. WELCOME TO THE BLUMHOUSE: BLACK BOX Emmanuel Osei-Kuffour Amazon / Blumhouse Productions EP: Jay Ellis, Jason Blum, Aaron Bergman PARADISE CITY*** (series) Ash Avildsen Sumerian Films EP: Lorenzo Antonucci PREACHER (season 3) Various AMC / Sony Pictures Television EP: Sam Catlin, Seth Rogen, Evan Goldberg ALTERED CARBON** (series) Various Netflix / Skydance EP: Laeta Kalogridis, James Middleton, Steve Blackman STAN AGAINST EVIL (series) Various IFC / Radical Media EP: Dana Gould, Frank Scherma, Tom Lassally BANSHEE (series) Ole Christian Madsen HBO / Cinemax Magnus Martens EP: Alan Ball THE VAMPIRE DIARIES (series) Various CW / Warner Bros. Television EP: Julie Plec, Kevin Williamson Feature Films PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. BROKE Carlyle Eubank Wild West Entertainment Prod: Wyatt Russell, Alex Hertzberg, Peter Billingsley THE TURNING Floria Sigismondi Amblin Partners 3 FROM HELL Rob Zombie Lionsgate FAMILY Laura Steinel Sony Pictures / Annapurna Pictures Official Selection: SXSW Film Festival Prod: Kit Giordano, Sue Naegle, Jeremy Garelick SILENCIO Lorena Villarreal 5100 Films / Prod: Beau Genot 31 Rob Zombie Lionsgate / Saban Films Official Selection: Sundance Film Festival Prod: Mike Elliot, Andy Gould THE QUIET ONES John Pogue Lionsgate / Exclusive Media LORDS OF SALEM Rob Zombie Blumhouse / Anchor Bay Entertainment LOVE & HONOR Danny Mooney IFC Films / Red 56 HALLOWEEN 2 Rob Zombie Dimension Films BUNRAKU* Guy Moshe Snoot Entertainment Official -

Donahue V. Artisan Entertainment 2002 U.S

Donahue v. Artisan Entertainment 2002 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 5930 United States District Court for the Southern District of New York April 5, 2002 HEATHER DONAHUE, MICHAEL C. WILLIAMS, JOSHUA G. LEONARD, Plaintiffs, against ARTISAN ENTERTAINMENT, INC., ARTISAN PICTURES INC, Defendants. 00 Civ. 8326 (JGK). 2002 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 5930. April 3, 2002, Decided. April 5, 2002, Filed. Counsel: For plaintiffs: Philip R. Hoffman, Pryor, Cashman, Sherman & Flynn, New York, New York. For defendants: Andrew J. Frack-man, O’Melveny & Myers, New York, New York. Before John G. Koeltl, United States District Judge. JOHN G. KOELTL, District Judge. Plaintiffs Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams, and Joshua G. Leonard bring this action against defendants Artisan Entertainment, Inc., and Artisan Pictures Inc. (collectively, “Artisan”) for breach of contract and violations of New York Civil Rights Law § 51, § 43(a) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a), and New York common law regarding unfair competition. The plaintiffs, who played the three central characters in the film “The Blair Witch Project” (“Blair Witch 1”), complain that their names and likenesses from that film, or other images of them, have been used without their approval in a sequel called “Blair Witch 2: Book of Shadows” (“Blair Witch 2”), as well as in promotions for that sequel and in other unauthorized ways. The defendants claim that each of the plaintiffs authorized these uses in their original acting contracts. The defendants now move for summary judgment on all claims. I The standard for granting summary judgment is well established. Summary judgment may not be granted unless “the pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and admissions on file, together with the affidavits, if any, show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the moving party is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law.”~ II There is no dispute as to the following facts except where specifically noted.