Steven Spielberg's Early Career As a Television Director at Universal Studios

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Las Aportaciones Al Cine De Steven Spielberg Son Múltiples, Pero Sobresale Como Director Y Como Productor

Steven Spielberg Las aportaciones al cine de Steven Spielberg son múltiples, pero sobresale como director y como productor. La labor de un productor de cine puede conllevar cierto control sobre las diversas atribuciones de una película, pero a menudo es poco más que aportar el dinero y los medios que la hacen posible sin entrar mucho en los aspectos creativos de la misma como el guión o la dirección. Es por este motivo que no me voy a detener en la tarea de Spielberg como productor más allá de señalar sus dos productoras de cine y algunas de sus producciones o coproducciones a modo de ejemplo, para complementar el vistazo a la enorme influencia de Spielberg en el mundo cinematográfico: En 1981 creó la productora de cine “Amblin Entertainment” junto con Kathleen Kenndy y Frank Marshall. El logo de esta productora pasaría a ser la famosa silueta de la bicicleta con luna llena de fondo de “ET”, la primera producción de la firma dirigida por Spielberg. Otras películas destacadas con participación de esta productora y no dirigidas por Spielberg son “Gremlins”, “Los Goonies”, “Regreso al futuro”, “Esta casa es una ruina”, “Fievel y el nuevo mundo”, “¿Quién engañó a Roger Rabbit?”, “En busca del Valle Encantado”, “Los picapiedra”, “Casper”, “Men in balck”, “Banderas de nuestros padres” & “Cartas desde Iwo Jima” o las series de televisión “Cuentos asombrosos” y “Urgencias” entre muchas otras películas y series. En 1994 fundaría con Jeffrey Katzenberg y David Geffen la productora y distribuidora DreamWorks, que venderían al estudio Viacom en 2006 tras participar en éxitos como “Shrek”, “American Beauty”, “Náufrago”, “Gladiator” o “Una mente maravillosa”. -

21, 2004 75 Cents

Volume117 Number 42 THURSDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2004 75 Cents Harry Trumbore/staff photographer ANSWERS WANTED—Township resident Jeffrey Muska rises during the Oct. 14 debate at ADDRESSING THE ISSUES—Mayor Thomas C. McDermott, at the podium, fields a question Wyoming Presbyterian Church to question the three candidates running for two seats on the from the audience during the Oct. 14 candidates’ debate at Wyoming Presbyterian Church. Township Committee in the general election Nov. 2. Approximately 40 residents attended the The two other candidates for two seats on the Township Committee, Daniel Baer and Linda forum, which was sponsored by the Wyoming Civic Association. Seelbach, await their turn to address the issues. Bickering dominates raucous Wyoming debate By Harry Trumbore and each other as well as the candi- velopment of the downtown busi- parties’ candidates on the nation- ing the Master Plan and not adher- ver bullet.” He charged, however, Eveline Speedie dates. ness district was needed to keep al level: Baer answered taxes were ing to it and charged the town- that the Master Plan was devised of The Item Nonetheless, the two incum- the township from losing its com- most important while his Republi- ship’s traffic issues have not been four years ago but that it is only this bents, Mayor Thomas C. McDer- petitive edge to communities such can opponents identified security resolved. Citing his 22 years of year, an election year, that his mott and Committeewoman Linda as Summit and Westfield. as the issue most important. experience in urban planning, he opponents are focusing on it and It was billed as a debate among Z. -

Public Works Director

RECRUITMENT PROFILE PUBLIC WORKS DIRECTOR The City of Woodstock is a true Midwestern city where community and quality of life are values revealed on every street and sidewalk. Beginning in the center of its historic Square and moving out to its farm-cushioned edge, Woodstock is truly unique, a place its citizens are proud to call home. This Recruitment Profile provides background information on the Community and City of Woodstock municipal operations, and outlines factors of qualification and experience identified as necessary and desirable for candidates for the Public Works Director Position. All inquiries relating to the recruitment and selection process are to be directed to the attention of: Deborah Schober, MS, SPHR, CLRP Human Resources Director City of Woodstock 121 W. Calhoun Street Woodstock, Illinois 60098 Email: [email protected] Phone: (815) 338-1172 COMMUNITY BACKGROUND History Industrial activity generally declined in Woodstock is located in McHenry County, Illinois, Woodstock after World War II. Yet, with reliable 55 miles northwest of Chicago. Originally the rail commuter transportation, the area became a town was called Centerville to attract the seat of destination for new residents fleeing Chicago's McHenry County government in 1842. The congestion. Residential construction boomed Centerville site was chosen when Alvin Judd after the 1960s, bringing with it both economic donated a two-acre public square for county prosperity and a lamented loss of a rural offices. The square became the hub of a city plat atmosphere. The revitalization of Woodstock's recorded in 1844. In 1845, the name was square, prominent in the 1993 movie Groundhog changed from Centerville to Woodstock, named Day, displayed this growing prosperity. -

Jack Jones Sings Mp3, Flac, Wma

Jack Jones Jack Jones Sings mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop Album: Jack Jones Sings Country: Japan Released: 2005 Style: Vocal MP3 version RAR size: 1657 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1878 mb WMA version RAR size: 1130 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 244 Other Formats: FLAC TTA WAV MP1 MP2 AUD XM Tracklist A1 A Day In The Life Of A Fool 2:20 A2 Autumn Leaves 3:19 A3 Somewhere There's Someone 2:16 A4 Watch What Happens 2:43 A5 People Will Say We're In Love 1:49 A6 Love After Midnight 2:40 B1 Somewhere My Love 2:20 B2 The Shining Sea 3:16 B3 The Face I Love 1:49 B4 Street Of Dreams 2:31 B5 The Snows Of Yesteryear 2:49 B6 I Don't Care Much 2:24 Credits Arranged By, Conductor – Ralph Carmichael Piano – Doug Talbert Notes Promotional Record Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Jack Jones Sings (LP, KS-3500 Jack Jones Kapp Records KS-3500 US 1966 Album) KS-3500, Jack Jones Sings Kapp Records, KS-3500, Jack Jones Japan 2005 UCCU-9149 (CD, Album, RE) Kapp Records UCCU-9149 KS-3500 Jack Jones Sings (LP, Album) Kapp Records KS-3500 Unknown Jack Jones Sings (LP, KL-1500 Jack Jones Kapp Records KL-1500 US 1966 Album, Mono) Jack Jones Sings (LP, KS 3500 Jack Jones Kapp Records KS 3500 Canada 1966 Album) Related Music albums to Jack Jones Sings by Jack Jones Jack Jones - The Weekend / Wildflower jack jones - Jack Jones - Bewitched Jack Jones - Four Great Songs From Four Great Shows Jack Jones - I'll Never Fall In Love Again Shirley Jones • Jack Cassidy • Susan Johnson • Frank Porretta - Brigadoon Tom Jones - Tom Jones Sings 24 Great Standards Jack Jones - The Impossible Dream (The Quest) / Strangers In The Night Jack Jones - Where Love Has Gone / People Jack Jones - Call Me Irresponsible. -

PLANNER PROJECT 2016... the 60S!

1 PLANNER PROJECT 2016... THE 60s! EDITOR’S NOTE: Listed below are the venues, performers, media, events, and specialty items including automobiles (when possible), highlighting 1961 and 1966 in Planner Project 2016! 1961! 1961 / FEATURED AREA MUSICAL VENUES FROM 1961 / (17) AREA JAZZ / BLUES VENUES / (4) Kornman’s Front Room / Leo’s Casino (4817 Central Ave.) / Theatrical Restaurant / Albert Anthony’s Welcome Inn AREA POP CULTURE VENUES / (13) Herman Pirchner’s Alpine Village / Aragon Ballroom / Cleveland Arena / the Copa (1710 Euclid) / Euclid Beach (hosts Coca-Cola Day) / Four Provinces Ballroom (free records for all attendees) / Hickory Grill / Homestead Ballroom / Keith’s 105th / Music Hall / Sachsenheim Ballroom / Severance Hall / Yorktown Lanes (Teen Age Rock ‘n Bowl’ night) 1961 / FEATURED ARTISTS / MUSICAL GRPS. PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / [Individuals: (36) / Grps.: (19)] [(-) NO. OF TIMES LISTED] FEATURED JAZZ / BLUES ARTISTS PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / (12) Gene Ammons / Art Blakely & the Jazz Messengers / John Coltrane / Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison / Ramsey Lewis / Jimmy McPartland / Shirley Scott / Jimmy Smith / Sonny Stitt / Stanley Turrentine / Joe Williams / Teddy Wilson POP CULTURE: FEATURED NORTHEAST OHIO / REGIONAL ARTISTS FROM 1961 / (6) Andrea Carroll / Ellie Frankel trio / Bobby Hanson’s Band / Dennis Warnock’s Combo / West Side Bandstand (with Jack Scott, Tom King & the Starfires) FEATURED NATIONAL ARTISTS PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / [Individuals: (16) / Groups: (14)] Tony Bennett / Jerry Butler / Cab Calloway (with All-Star -

Available Videos for TRADE (Nothing Is for Sale!!) 1

Available Videos For TRADE (nothing is for sale!!) 1/2022 MOSTLY GAME SHOWS AND SITCOMS - VHS or DVD - SEE MY “WANT LIST” AFTER MY “HAVE LIST.” W/ O/C means With Original Commercials NEW EMAIL ADDRESS – [email protected] For an autographed copy of my book above, order through me at [email protected]. 1966 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS and NBC Fall Schedule Preview 1997 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS Fall Schedule Preview (not for trade) Many 60's Show Promos, mostly ABC Also, lots of Rock n Roll movies-“ROCK ROCK ROCK,” “MR. ROCK AND ROLL,” “GO JOHNNY GO,” “LET’S ROCK,” “DON’T KNOCK THE TWIST,” and more. **I ALSO COLLECT OLD 45RPM RECORDS. GOT ANY FROM THE FIFTIES & SIXTIES?** TV GUIDES & TV SITCOM COMIC BOOKS. SEE LIST OF SITCOM/TV COMIC BOOKS AT END AFTER WANT LIST. Always seeking “Dick Van Dyke Show” comic books and 1950s TV Guides. Many more. “A” ABBOTT & COSTELLO SHOW (several) (Cartoons, too) ABOUT FACES (w/o/c, Tom Kennedy, no close - that’s the SHOW with no close - Tom Kennedy, thankfully has clothes. Also 1 w/ Ben Alexander w/o/c.) ACADEMY AWARDS 1974 (***not for trade***) ACCIDENTAL FAMILY (“Making of A Vegetarian” & “Halloween’s On Us”) ACE CRAWFORD PRIVATE EYE (2 eps) ACTION FAMILY (pilot) ADAM’S RIB (2 eps - short-lived Blythe Danner/Ken Howard sitcom pilot – “Illegal Aid” and rare 4th episode “Separate Vacations” – for want list items only***) ADAM-12 (Pilot) ADDAMS FAMILY (1ST Episode, others, 2 w/o/c, DVD box set) ADVENTURE ISLAND (Aussie kid’s show) ADVENTURER ADVENTURES IN PARADISE (“Castaways”) ADVENTURES OF DANNY DEE (Kid’s Show, 30 minutes) ADVENTURES OF HIRAM HOLLIDAY (8 Episodes, 4 w/o/c “Lapidary Wheel” “Gibraltar Toad,”“ Morocco,” “Homing Pigeon,” Others without commercials - “Sea Cucumber,” “Hawaiian Hamza,” “Dancing Mouse,” & “Wrong Rembrandt”) ADVENTURES OF LUCKY PUP 1950(rare kid’s show-puppets, 15 mins) ADVENTURES OF A MODEL (Joanne Dru 1956 Desilu pilot. -

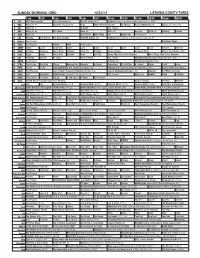

Sunday Morning Grid 12/21/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/21/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Kansas City Chiefs at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Young Men Big Dreams On Money Access Hollywood (N) Skiing U.S. Grand Prix. 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. Outback Explore 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Atlanta Falcons at New Orleans Saints. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Christmas Angel 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Alsace-Hubert Heirloom Meals Man in the Kitchen (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Christmas Twister (2012) Casper Van Dien. (PG) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

1001 Classic Commercials 3 DVDS

1001 classic commercials 3 DVDS. 16 horas de publicidad americana de los años 50, 60 y 70, clasificada por sectores. En total, 1001 spots. A continuación, una relación de los spots que puedes disfrutar: FOOD (191) BEVERAGES (47) 1. Coca-Cola: Arnold Palmer, Willie Mays, etc. (1960s) 2. Coca-Cola: Mary Ann Lynch - Stewardess (1960s) 3. Coca-Cola: 7 cents off – Animated (1960s) 4. Coca-Cola: 7 cents off – Animated (1960s) 5. Coca-Cola: “Everybody Need a Little Sunshine” (1960s) 6. Coca-Cola: Fortunes Jingle (1960s) 7. Coca-Cola: Take 5 – Animated (1960s) 8. Pet Milk: Mother and Child (1960s) 9. 7UP: Wet and Wild (1960s) 10. 7UP: Fresh Up Freddie – Animated (1960s) 11. 7UP: Peter Max-ish (1960s) 12. 7UP: Roller Coaster (1960s) 13. Kool Aid: Bugs Bunny and the Monkees (1967) 14. Kool Aid: Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd Winter Sports (1965) 15. Kool Aid: Mom and kids in backyard singing (1950s) 16. Shasta Orange: Frankenstein parody Narrated by Tom Bosley and starring John Feidler (1960s) 17. Shasta Cola: R. Crumb-ish animation – Narrated by Tom Bosley (1960s) 18. Shasta Cherry Cola: Car Crash (1960s) 19. Nestle’s Quick: Jimmy Nelson, Farfel & Danny O’Day (1950s) 20. Tang: Bugs Bunny & Daffy Duck Shooting Gallery (1960s) 21. Gallo Wine: Grenache Rose (1960s) 22. Tea Council: Ed Roberts (1950s) 23. Evaporated Milk: Ed & Helen Prentiss (1950s) 24. Prune Juice: Olan Soule (1960s) 25. Carnation Instant Breakfast: Outer Space (1960s) 26. Carnation Instant Breakfast: “Really Good Days!” (1960s) 27. Carnation: “Annie Oakley” 28. Carnation: Animated on the Farm (1960s) 29. Carnation: Fresh From the Dairy (1960s) 30. -

Business AD-Vantage

PAGE 8 PRESS & DAKOTAN n MONDAY, DECEMBER 28, 2015 ecutor who parlayed his handling Bobbi Kris- it to Me,” on the hit comedy show. a prominent figure in Margaret vehicles ranging from the beautiful of the Charles Manson trial into tina Brown, Sept. 3. Thatcher’s government but helped to the outrageous. Nov. 5. a career as a bestselling author. 22. Daughter of William Grier, 89. Psychiatrist bring about her downfall after they Gunnar Hansen, 68. He Deaths June 6. singers Whitney who co-authored the groundbreak- parted ways over policy toward played the iconic villain Leather- From Page 7 Christopher Lee, 93. Actor Houston and ing 1968 book, “Black Rage,” Europe. Oct. 9. face in the original “Texas Chain who brought dramatic gravitas Bobby Brown, which offered the first psychologi- Jerry Parr, 85. Secret Ser- Saw Massacre” film. Nov. 7. Pan- and aristocratic bearing to screen she was raised cal examination of black life in the vice agent credited with saving creatic cancer. the hail of snowballs and shower villains from Dracula to the wicked in the shadow United States. Sept. 3. President Ronald Reagan’s life Helmut Schmidt, 96. Former of boos that rained down on him. wizard Saruman in “The Lord of of fame and Martin Milner, 83. His whole- on the day he was shot outside a chancellor who guided West April 30. the Rings” trilogy. June 7. shattered by some good looks helped make Washington hotel. Oct. 9. Germany through economic turbu- Vincent Musetto, 74. Veteran Walter Dale the loss of her him the star of two hugely popular Richard Heck, 84. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

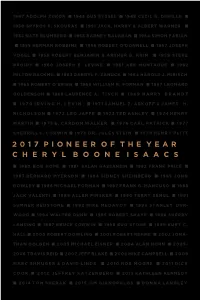

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner. -

Highland Historical Society Highlights Highland, Illinois January, 2013______

Highland Historical Society Highlights Highland, Illinois_ January, 2013_______________________ NEXT QUARTERLY MEETING WILL BE 7:00PM, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 9, 2013 AT FAITH COUNTRYSIDE ATRIUM APARTMENTS Highland, IL TH 1331 26 Street The once popular TV show Route 66 shot an episode, partly in Highland, in the fall of 1962 We plan to show a 1963 TV show: “Soda (October 27-November 5, 1962) which was Pop and Paper Flags,” which was partially aired on May 31, 1963 as Episode 31, the last shot in Highland, Illinois. of the Third Season. This is also our “Show and Tell” meeting, In the first three seasons the show starred so bring your area items to share. Martin Milner (1931-) (better known for his 174 ________________________________________ episodes of Adam-12), in the role of Tod Stiles NOTE THE DUES INVOICE IN THIS MAILING and George Maharis (1928-)(a top-40 singer in 1962), in the role of Buz Murdock, his sidekick. Most members will receive a Membership George Maharis apparently came to Highland Renewal Form with this newsletter. These for the filming, but he quit the show due to dues statements are for the calendar year health issues and does not appear in the final 2013, and are due upon receipt. Some version shown or in the credits. members are lifetime members. If we send you an invoice and you think it is a mistake, The scenes he filmed here were cut from the please contact us, and clarify our records. final show and the new sidekick filmed similar Make checks payable to “Highland Historical scenes in Florida that were then blended in.