Connectivity-Related Projects in Europe and China. Opportunities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical GIS: Mapping the Bucharest Geographies of the Pre-Socialist Industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru

# Gabriel Simion et al. Human Geographies – Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography Vol. 10, No. 2, November 2016 | www.humangeographies.org.ro ISSN–print: 1843–6587 | ISSN–online: 2067–2284 Historical GIS: mapping the Bucharest geographies of the pre-socialist industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru University of Bucharest, Romania This article aims to map the manner in which the rst industrial units crystalized in Bucharest and their subsequent dynamic. Another phenomenon considered was the way industrial sites grew and propagated and how the rst industrial clusters formed, thus amplifying the functional variety of the city. The analysis was undertaken using Historical GIS, which allowed to integrate elements of industrial history with the location of the most important industrial objectives. Working in GIS meant creating a database with the existing factories in Bucharest, but also those that had existed in different periods. Integrating the historical with the spatial information about industry in Bucharest was preceded by thorough preparations, which included geo-referencing sources (city plans and old maps) and rectifying them. This research intends to serve as an example of how integrating past and present spatial data allows for the analysis of an already concluded phenomenon and also explains why certain present elements got to their current state.. Key Words: historical GIS, GIS dataset, Bucharest. Article Info: Received: September 5, 2016; Revised: October 24, 2016; Accepted: November 15, 2016; Online: November 30, 2016. Introduction The spatial evolution of cities starting with the ending of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th is closely connected to their industrial development. -

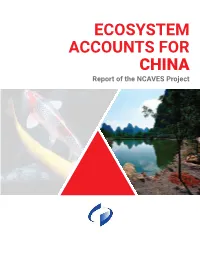

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

ESMP) OBOR FIRE-FIGHTING DETACHMENT, Bucharest

Ministry of Internal Affairs Department of Emergency Situations General Inspectorate for Emergency Situations ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) OBOR FIRE-FIGHTING DETACHMENT, Bucharest July 2021 1 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 10 1.1 11 1.2 11 1.3 12 1.4 13 2. LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK 15 2.1 NATIONAL LEGAL ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL REGULATORY FRAMEWORK 15 3. WORLD BANK SAFEGUARDS POLICIES 19 4. OBOR SUB-PROJECT DESCRIPTION 21 4.1 SUB-PROJECT SITE LOCATION AND CHARACTERISTICS 21 4.2 CURRENT STATE OF EXISTING BUILDINGS 22 4.3 PROPOSED DEMOLITION WORKS 23 4.4 PROPOSED NEW BUILDING CONSTRUCTION 24 4.5 TEMPORARY FACILITIES REQUIRED DURING CONSTRUCTION PHASE 27 5. ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACTS AND RISK ASSESSMENT OF SUB-PROJECT ACTIVITIES 28 CONSIDERATIONS ON BUILDIG HYSTORY AND CURRENT SITUATION 28 5.1 PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS AND RISKS 31 5.2 PROJECT SOCIAL IMPACTS AND RISKS 32 6. ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN 34 6.1 ENVIRONMENTAL GUIDELINES 34 6.2. OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY 36 7. ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MONITORING PLAN 38 8. IMPLEMENTATION ARRANGEMENTS 39 8.1. INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENT FOR PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION 39 8.2 INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR ESMP IMPLEMENTATION 42 8.3 CAPACITY BUILDING AND TRAINING 42 9. MONITORING, SUPERVISION AND REPORTING 43 2 10. STAKEHOLDERS ENGAGEMENT AND INFORMATION DISCLOSURE 45 10.1. STAKEHOLDER MAPPING 45 10.2. Error! Bookmark not defined. 11. 48 12. 49 ANNEX 1. GENERAL ENVIRONMENTAL FRAMEWORK AND GUIDELINES 49 ANNEX -

Trasee De Noapte

PROGRAMUL DE TRANSPORT PENTRU RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE - TRASEE DE NOAPTE Plecari de la capete de Linia Nr Numar vehicule Nr statii TRASEU CAPETE lo traseu Lungime c 23 00:30 1 2 03:30 4 5 Prima Ultima Dus: Şos. Colentina, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. Ferdinand, Şos. Pantelimon, Str. Gǎrii Cǎţelu, Str. N 101 Industriilor, Bd. Basarabia, Bd. 1 Dus: Decembrie1918 0 2 2 0 2 0 0 16 statii Intors: Bd. 1 Decembrie1918, Bd. 18.800 m Basarabia, Str. Industriilor, Str. Gǎrii 88 Intors: Cǎţelu, Şos. Pantelimon, Bd. 16 statii Ferdinand, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Şos. 18.400 m Colentina. Terminal 1: Pasaj Colentina 00:44 03:00 Terminal 2: Faur 00:16 03:01 Dus: Piata Unirii , Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Universitatii, Bd. Carol I, Bd. Pache Protopopescu, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Str. Vatra Luminoasa, Bd. N102 Pierre de Coubertin, Sos. Iancului, Dus: Sos. Pantelimon 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 19 statii Intors: Sos. Pantelimon, Sos. Iancului, 8.400 m Bd. Pierre de Coubertin, Str. Vatra 88 Intors: Luminoasa, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. 16 statii Pache Protopopescu, Bd. Carol I, 8.600 m Piata Universitatii, Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Unirii. Terminal 1: Piata Unirii 2 23:30 04:40 Terminal 2: Granitul 22.55 04:40 Dus: Bd. Th. Pallady, Bd. Camil Ressu, Cal. Dudeşti, Bd. O. Goga, Str. Nerva Traian, Cal. Văcăreşti, Şos. Olteniţei, Str. Ion Iriceanu, Str. Turnu Măgurele, Str. Luică, Şos. Giurgiului, N103 Piaţa Eroii Revoluţiei, Bd. Pieptănari, us: Prelungirea Ferentari 0 2 1 0 2 0 0 24 statii Intors: Prelungirea Ferentari, , Bd. -

Bucharest Meet: Iuliu Maniu and Vasile Milea

#welcome @ CAMPUS 6 swipe page to begin Homepage #theagenda 1.0 Futureproof 2.0 Location & Amenities 3.0 Site Plan 4.0 Placemaking & Social Impact 5.0 Interior & Innovations 6.0 Green Features 7.0 About Us 8.0 Contact 1.0 Futureproof 1 Architecture 2 Placemaking 3 Art We stand by our promise to deliver high-class offices, combining the best design practices, the principles of sustainable development and technological innovation. We offer our customers solutions that support their present and future needs. 1 Products 1 Wellbeing 2 Connected by Skanska 2 Biodiversity 3 BIM 3 Certification 1.0 Futureproof We are constantly looking for new materials and technological solutions so that our buildings are ready for the challenges of the future. INNOVATIONS What does it mean to us? Trends come and go and style evolves. Futureproof is a symbol that defines the focus areas that make Skanska a trustworthy partner. Our investments are determined by functionality, low maintenance costs and minimal impact on the environment. Located in the best spots in the city, they are highly valuable assets on the office buildings market. Sustainable development is in our company’s DNA, therefore we design and construct our buildings aiming to benefit the society and respect the environment. SUSTAINABILITY Based on our Scandinavian roots and cooperation with top-notch architects, we provide timeless and functional design of our buildings. DESIGN 2.0 Location & Amenities #welcome We designed Campus 6 with one goal: to change Campus the way people mix life and work. 6.1 Q3 2018 Campus sqm 6.2 81 000 GLA in 4 phases Q4 2019 1 000 parking places floors of office spaces Campus 10 6.3 Q3 2021 Campus 6.4 Q4 2022 POLITEHNICA UNIVERSITY Campus 6.3 Campus 6.4 Campus 6.2 Campus 6.1 Iuliu Maniu Ave. -

Prodigals in Love: Narrating Gay Identity and Collectivity on the Early Internet in China

Prodigals in Love: Narrating Gay Identity and Collectivity on the Early Internet in China by Gang Pan A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Gang Pan 2015 Prodigals in Love: Narrating Gay Identity and Collectivity on the Early Internet in China Gang Pan Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2015 Abstract This dissertation concerns itself with the eruption of a large number of gay narratives on the Chinese internet in its first decade. There are two central arguments. First, the composing and sharing of narratives online played the role of a social movement that led to the formation of gay identity and collectivity in a society where open challenges to the authorities were minimal. Four factors, 1) the primacy of the internet, 2) the vernacular as an avenue of creativity and interpretation, 3) the transitional experience of the generation of the internet, and 4) the evolution of gay narratives, catalyzed by the internet, enhanced, amplified, and interacted with each other in a highly complicated and accelerated dynamic, engendered a virtual gay social movement. Second, many online gay narratives fall into what I term “prodigal romance,” which depicts gay love as parent-obligated sons in love with each other, weaving in violent conflicts between desire and duty in its indigenous context. The prodigal part of this model invokes the archetype of the Chinese prodigal, who can only return home having excelled and with the triumph of his journey. -

Component 1. Elaboration of Bucharest's Iuds, Capital

ROMANIA Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program (P169577) COMPONENT 1. ELABORATION OF BUCHAREST’S IUDS, CAPITAL INVESTMENT PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT Output 3. Urban context and identification of key local issues and needs, and visions and objectives of IUDS and Identification of a long list of projects. Chapter 3. Spatial and Functional Profile March 2021 DISCLAIMER This report is a product of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/the World Bank. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. This report does not necessarily represent the position of the European Union or the Romanian Government. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable laws. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with the complete information to either: (i) the Municipality of Bucharest (Bd. Regina Elisabeta 47, Bucharest, Romania); or (ii) the World Bank Group Romania (Str. Vasile Lascăr 31, et. 6, Sector 2, Bucharest, Romania). This report was delivered in March 2021 under the Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program, concluded between the Municipality of Bucharest and the -

ECOSYSTEM ACCOUNTS for CHINA Report of the NCAVES Project Citation and Reproduction

ECOSYSTEM ACCOUNTS FOR CHINA Report of the NCAVES Project Citation and reproduction NBS China 2021. Ecosystem Accounts for China. Results of the NCAVES Project. Cover images: Sergio Capuzzimati and Tom Rickhuss Disclaimer The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in the text are not necessarily those of the United Nations or European Union or other agencies involved. The designations employed and the presentation of material including on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations or European Union concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. CONTENTS Preface and Acknowledgements .............................................................................. 5 Acronyms ....................................................................................................................... 6 Annotated Outline ......................................................................................................... 8 Section 1 : Introduction ...................................................................................... 9 1.1 Context .................................................................................................................... 9 1.1.1 The importance of SEEA in a policy context .............................................9 1.1.2 Country context .......................................................................................... 10 1.2 -

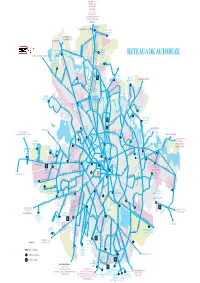

Autobuze.Pdf

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 261 BANEASA RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE 204 205 304 Sisesti 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 112 205 261 COMPLEX 131 261301 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti COMERCIAL CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucu Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 COLOSSEUM 203 335 361 605 780 783 Bd.R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 112 Aerogarii R402 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 restii Noi DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 331 R436 CFR 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 112 135 243 Str. Jiului Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Sos. Chitilei 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Poligrafiei 231 243 Str. Peris 780 783 331 PIATA Str.Oi 243 382 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 243 382 R447PRESEI R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 243 131 203 205 261 304 135 343 105 203 231 tuz CARTIER 261 304 330 361 605 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 Bd. Marasti GIULESTI-SARBI 162 R441 R442 R443 r a lo c i s Bd. Expozitiei231 330 r o a dronache 162 163 105 780 R444 R446t e R409 243 343 Str. Sportului a r 105 i CLABUCET R447 o v l F 381 R448 A . -

Analysis of the Chinese PVC Industry Is Carried Out

Analysis of the Chinese PVC Industry Researched and written by Daisy Du and Noam David Stern Shanghai, March 2021 1 List of Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Main Supply and Usage of PVC Resin and PVC Products in China 3 3. Use of Lead Stabilizers and the Regulatory Environment in China 8 4. Use of Problematic Phthalates Plasticizers (DEHP) and the Regulatory 10 Environment in China 5. Waste management and Recycling 12 6. Barriers for Substitution of Lead Stabilizers and Toxic Phthalates Plasticizers 16 7. Summary and Conclusions 19 8. Way Forward/Next Step 20 Appendix 1: Relevant Stakeholders 22 Appendix 2: Regulations and Standards Restricting the Use of Lead 27 Stabilizers Appendix 3: China National Standards and Industry Standards Restricting 32 the Use of Toxic Phthalates Plasticizers 1. Introduction PVC plastics that contain chemical additives such as Lead stabilizers and DEHP plasticizers have a proven harmful effect on human health and the environment. In the EU, the use of these toxic additives in PVC products has been restricted or banned and replaced by safer alternatives. Since these regulatory changes have mostly been confined to the EU and not implemented on a wider international scale, increasing the sustainability awareness and promoting the voluntary substitution of these additives in countries like China has become a top priority. With the adoption of China’s 13th Five-year Plan (2016-2020), high-end, intelligent and green production became a key policy priority to promote the overall improvement of the manufacturing industry. In the upcoming 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025), the Chinese government is once again stressing the importance of protecting the environment. -

Trading Into a Bright Energy Future: the Case for Open, High-Quality

Trading into a bright energy future The case for open, high-quality solar photovoltaic markets This publication and any opinions reflected therein are the sole responsibility of its authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of members of the WTO. This publication and the material herein are provided by IRENA “as is”. All reasonable precautions have been taken by IRENA to verify the reliability of the material in this publication. However, neither IRENA nor any of its officials, agents, data or other third- party content providers provides a warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied, and they accept no responsibility or liability for any consequence of use of the publication or material herein. The information contained herein does not necessarily represent the views of all Members of IRENA. The mention of specific companies or certain projects or products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by IRENA in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The designations employed and the presentation of material herein do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of IRENA concerning the legal status of any region, country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of frontiers or boundaries. Acknowledgements This information note has been prepared under the overall guidance of Hoe Lim of the WTO and Francisco Boshell of IRENA. The core team was composed of Stefan Maximilian Gahrens and Alessandra Salgado of IRENA and Karsten Steinfatt of the WTO. In addition, Adelina Mendoza and Edvinas Drevinskas of the WTO provided statistical support. -

Paliwa Alkoholowe Dla Transportu

Paliwa alkoholowe dla transportu Alcohol fuels for transport – uwarunkowania, badania i rozwój – background, research and development Alcohol fuels for transport – background, research and development Praca zbiorowa pod redakcją Stanisława Oleksiaka Paliwa alkoholowe dla transportu – uwarunkowania, badania i rozwój Alcohol fuels for transport – background, research and development Instytut Nafty i Gazu – Państwowy Instytut Badawczy 2015 Redakcja naukowa: Maria Ciechanowska Wiesława Urzędowska Jacek Jaworski Jan Lubaś Piotr Such Praca zbiorowa pod redakcją dr. inż. Stanisława Oleksiaka DOI: 10.18668/PN2015.204 Niniejsza monografia związana jest z projektem realizowanym w INiG – PIB i finansowa- nym ze środków funduszy norweskich, w ramach programu Polsko-Norweska Współpraca Badawcza realizowanego przez Narodowe Centrum Badań i Rozwoju. Wydawca: Instytut Nafty i Gazu – Państwowy Instytut Badawczy ul. Lubicz 25A 31-503 Kraków Redaktor wydania: Agnieszka J. Kozak Korekta językowa: Katarzyna Wróbel, Brian Scott Skład i łamanie, DTP, projekt okładki: Paweł Noszkiewicz Druk i oprawa: Drukarnia K&K reklama i poligrafia ul. Ostatnia 22 31-444 Kraków Nakład: 135 egz. Copyright © 2015 INiG – PIB Kraków, ul. Lubicz 25A, Poland ISSN 2353-2718 Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone. Żadna część niniejszej publikacji nie może być, bez uprzedniej pisemnej zgody wydawcy, gromadzona w systemach zbierania informacji, transmitowana lub reprodukowana, włączając w to fotokopie, fotografie, zapis magnetyczny lub inny. Prenumeratę i wysyłkę prac naukowo-badawczych oraz