Oxycodone/Naloxone in the Management of Patients with Pain and Opioid–Induced Bowel Dysfunction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RELISTOR, INN: Methylnaltrexone Bromide

The European Medicines Agency Evaluation of Medicines for Human Use EMEA/CHMP/10906/2008 ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR RELISTOR International Nonproprietary Name: METHYLNALTREXONE BROMIDE Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/870 Assessment Report as adopted by the CHMP with all information of a commercially confidential nature deleted. 7 Westferry Circus, Canary Wharf, London, E14 4HB, UK Tel. (44-20) 74 18 84 00 Fax (44-20) 74 18 8613 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.emea.eu.int TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE PROCEDURE......................................... 3 1.1 Submission of the dossier ...................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Steps taken for the assessment of the product ....................................................................... 3 2 SCIENTIFIC DISCUSSION............................................................................................... 4 2.1 Introduction............................................................................................................................ 4 2.2 Quality aspects....................................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Non-clinical aspects............................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Clinical aspects .................................................................................................................... 13 2.5 Pharmacovigilance...............................................................................................................41 -

Albany-Molecular-Research-Regulatory

PRODUCT CATALOGUE API COMMERCIAL US EU Japan US EU Japan API Name Site CEP India API Name Site CEP India DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF A Abiraterone Malta • Benztropine Mesylate Cedarburg • Adenosine Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi • • * Betaine Citrate Anhydrous Bon Encontre • Betametasone-17,21- Alcaftadine Spain Spain • • Dipropionate Sterile • Alclometasone-17, 21- Spain Betamethasone Acetate Spain Dipropionate • • Altrenogest Spain • • Betamethasone Base Spain Amphetamine Aspartate Rensselaer Betamethasone Benzoate Spain * Monohydrate Milled • Betamethasone Valerate Amphetamine Sulfate Rensselaer Spain * • Acetate Betamethasone-17,21- Argatroban Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi Spain • • Dipropionate • • • Atenolol India • • Betamethasone-17-Valerate Spain • • Betamethasone-21- Atracurium Besylate Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi Spain • Phosphate Disodium Salt • • Bromfenac Monosodium Atropine Sulfate Cedarburg Lodi * • Salt Sesquihydrate • • Azanidazole Lodi Bromocriptine Mesylate Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi • • • • • Azelastine HCl Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi • • Budesonide Spain • • Aztreonam Rozzano - Valle Ambrosia • • Budesonide Sterile Spain • • B Bamifylline HCl Bon Encontre • Butorphanol Tartrate Cedarburg • Beclomethasone-17, 21- Spain Capecitabine Lodi Dipropionate • C • 2 *Please contact our Accounts Managers in case you are interested in this API. 3 PRODUCT CATALOGUE API COMMERCIAL US EU Japan US EU Japan API Name Site CEP India API Name Site CEP India DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF Dexamethasone-17,21- Carbimazole Bon Encontre Spain • Dipropionate -

Design and Synthesis of Cyclic Analogs of the Kappa Opioid Receptor Antagonist Arodyn

Design and synthesis of cyclic analogs of the kappa opioid receptor antagonist arodyn By © 2018 Solomon Aguta Gisemba Submitted to the graduate degree program in Medicinal Chemistry and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Blake Peterson Co-Chair: Dr. Jane Aldrich Dr. Michael Rafferty Dr. Teruna Siahaan Dr. Thomas Tolbert Date Defended: 18 April 2018 The dissertation committee for Solomon Aguta Gisemba certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Design and synthesis of cyclic analogs of the kappa opioid receptor antagonist arodyn Chair: Dr. Blake Peterson Co-Chair: Dr. Jane Aldrich Date Approved: 10 June 2018 ii Abstract Opioid receptors are important therapeutic targets for mood disorders and pain. Kappa opioid receptor (KOR) antagonists have recently shown potential for treating drug addiction and 1,2,3 4 8 depression. Arodyn (Ac[Phe ,Arg ,D-Ala ]Dyn A(1-11)-NH2), an acetylated dynorphin A (Dyn A) analog, has demonstrated potent and selective KOR antagonism, but can be rapidly metabolized by proteases. Cyclization of arodyn could enhance metabolic stability and potentially stabilize the bioactive conformation to give potent and selective analogs. Accordingly, novel cyclization strategies utilizing ring closing metathesis (RCM) were pursued. However, side reactions involving olefin isomerization of O-allyl groups limited the scope of the RCM reactions, and their use to explore structure-activity relationships of aromatic residues. Here we developed synthetic methodology in a model dipeptide study to facilitate RCM involving Tyr(All) residues. Optimized conditions that included microwave heating and the use of isomerization suppressants were applied to the synthesis of cyclic arodyn analogs. -

A Review of Unique Opioids and Their Conversions

A Review of Unique Opioids and Their Conversions Jacqueline Cleary, PharmD, BCACP Assistant Professor Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences Adjunct Professor SAGE College of Nursing DISCLOSURES • Kaleo • Remitigate, LLC OBJECTIVES • Compare and contrast unique pharmacotherapy options for the treatment of chronic pain including: methadone, buprenoprhine, tapentadol, and tramadol • Select methadone, buprenorphine, tapentadol, or tramadol based on patient specific factors • Apply appropriate opioid conversion strategies to unique opioids • Understand opioid overdose risk surrounding opioid conversions and the use of unique opioids UNIQUE OPIOIDS METHADONE, BUPRENORPHINE, TRAMADOL, TAPENTADOL METHADONE My favorite drug because….? METHADONE- INDICATIONS • FDA labeled indications – (1) chronic pain (2) detoxification Oral soluble tablets for suspension NOT indicated for chronic pain treatment • Initial inpatient detoxification of opioids by a licensed trained provider with methadone and supportive care is appropriate • Methadone maintenance provider must have special credentialing and training as required by state Outpatient prescription must be for pain ONLY and say “for pain” on RX • Continuation of methadone maintenance from outside provider while patient is inpatient for another condition is appropriate http://cdn.atforum.com/wp-content/uploads/SAMHSA-2015-Guidelines-for-OTPs.pdf MECHANISM OF ACTION • Potent µ-opioid agonist • NMDA receptor antagonist • Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor • Serotonin reuptake inhibitor ADVERSE EVENTS -

Methylnaltrexone Nonf

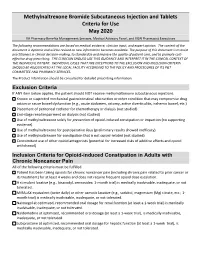

Methylnaltrexone Bromide Subcutaneous Injection and Tablets Criteria for Use May 2020 VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives The following recommendations are based on medical evidence, clinician input, and expert opinion. The content of the document is dynamic and will be revised as new information becomes available. The purpose of this document is to assist practitioners in clinical decision-making, to standardize and improve the quality of patient care, and to promote cost- effective drug prescribing. THE CLINICIAN SHOULD USE THIS GUIDANCE AND INTERPRET IT IN THE CLINICAL CONTEXT OF THE INDIVIDUAL PATIENT. INDIVIDUAL CASES THAT ARE EXCEPTIONS TO THE EXCLUSION AND INCLUSION CRITERIA SHOULD BE ADJUDICATED AT THE LOCAL FACILITY ACCORDING TO THE POLICY AND PROCEDURES OF ITS P&T COMMITTEE AND PHARMACY SERVICES. The Product Information should be consulted for detailed prescribing information. Exclusion Criteria If ANY item below applies, the patient should NOT receive methylnaltrexone subcutaneous injections. Known or suspected mechanical gastrointestinal obstruction or other condition that may compromise drug action or cause bowel dysfunction (e.g., acute abdomen, ostomy, active diverticulitis, ischemic bowel, etc.) Placement of peritoneal catheter for chemotherapy or dialysis (not studied) End-stage renal impairment on dialysis (not studied) Use of methylnaltrexone solely for prevention of opioid-induced constipation or impaction (no supporting evidence). Use of methylnaltrexone for postoperative ileus (preliminary results showed inefficacy). Use of methylnaltrexone for constipation that is not opioid-related (not studied) Concomitant use of other opioid antagonists (potential for increased risks of additive effects and opioid withdrawal) Inclusion Criteria for Opioid-induced Constipation in Adults with Chronic Noncancer Pain All of the following criteria must be fulfilled. -

Pain Management & Palliative Care

Guidelines on Pain Management & Palliative Care A. Paez Borda (chair), F. Charnay-Sonnek, V. Fonteyne, E.G. Papaioannou © European Association of Urology 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 6 1.1 The Guideline 6 1.2 Methodology 6 1.3 Publication history 6 1.4 Acknowledgements 6 1.5 Level of evidence and grade of guideline recommendations* 6 1.6 References 7 2. BACKGROUND 7 2.1 Definition of pain 7 2.2 Pain evaluation and measurement 7 2.2.1 Pain evaluation 7 2.2.2 Assessing pain intensity and quality of life (QoL) 8 2.3 References 9 3. CANCER PAIN MANAGEMENT (GENERAL) 10 3.1 Classification of cancer pain 10 3.2 General principles of cancer pain management 10 3.3 Non-pharmacological therapies 11 3.3.1 Surgery 11 3.3.2 Radionuclides 11 3.3.2.1 Clinical background 11 3.3.2.2 Radiopharmaceuticals 11 3.3.3 Radiotherapy for metastatic bone pain 13 3.3.3.1 Clinical background 13 3.3.3.2 Radiotherapy scheme 13 3.3.3.3 Spinal cord compression 13 3.3.3.4 Pathological fractures 14 3.3.3.5 Side effects 14 3.3.4 Psychological and adjunctive therapy 14 3.3.4.1 Psychological therapies 14 3.3.4.2 Adjunctive therapy 14 3.4 Pharmacotherapy 15 3.4.1 Chemotherapy 15 3.4.2 Bisphosphonates 15 3.4.2.1 Mechanisms of action 15 3.4.2.2 Effects and side effects 15 3.4.3 Denosumab 16 3.4.4 Systemic analgesic pharmacotherapy - the analgesic ladder 16 3.4.4.1 Non-opioid analgesics 17 3.4.4.2 Opioid analgesics 17 3.4.5 Treatment of neuropathic pain 21 3.4.5.1 Antidepressants 21 3.4.5.2 Anticonvulsant medication 21 3.4.5.3 Local analgesics 22 3.4.5.4 NMDA receptor antagonists 22 3.4.5.5 Other drug treatments 23 3.4.5.6 Invasive analgesic techniques 23 3.4.6 Breakthrough cancer pain 24 3.5 Quality of life (QoL) 25 3.6 Conclusions 26 3.7 References 26 4. -

Patent Application Publication ( 10 ) Pub . No . : US 2019 / 0192440 A1

US 20190192440A1 (19 ) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10) Pub . No. : US 2019 /0192440 A1 LI (43 ) Pub . Date : Jun . 27 , 2019 ( 54 ) ORAL DRUG DOSAGE FORM COMPRISING Publication Classification DRUG IN THE FORM OF NANOPARTICLES (51 ) Int . CI. A61K 9 / 20 (2006 .01 ) ( 71 ) Applicant: Triastek , Inc. , Nanjing ( CN ) A61K 9 /00 ( 2006 . 01) A61K 31/ 192 ( 2006 .01 ) (72 ) Inventor : Xiaoling LI , Dublin , CA (US ) A61K 9 / 24 ( 2006 .01 ) ( 52 ) U . S . CI. ( 21 ) Appl. No. : 16 /289 ,499 CPC . .. .. A61K 9 /2031 (2013 . 01 ) ; A61K 9 /0065 ( 22 ) Filed : Feb . 28 , 2019 (2013 .01 ) ; A61K 9 / 209 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 9 /2027 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 31/ 192 ( 2013. 01 ) ; Related U . S . Application Data A61K 9 /2072 ( 2013 .01 ) (63 ) Continuation of application No. 16 /028 ,305 , filed on Jul. 5 , 2018 , now Pat . No . 10 , 258 ,575 , which is a (57 ) ABSTRACT continuation of application No . 15 / 173 ,596 , filed on The present disclosure provides a stable solid pharmaceuti Jun . 3 , 2016 . cal dosage form for oral administration . The dosage form (60 ) Provisional application No . 62 /313 ,092 , filed on Mar. includes a substrate that forms at least one compartment and 24 , 2016 , provisional application No . 62 / 296 , 087 , a drug content loaded into the compartment. The dosage filed on Feb . 17 , 2016 , provisional application No . form is so designed that the active pharmaceutical ingredient 62 / 170, 645 , filed on Jun . 3 , 2015 . of the drug content is released in a controlled manner. Patent Application Publication Jun . 27 , 2019 Sheet 1 of 20 US 2019 /0192440 A1 FIG . -

AMRI India Pvt

WE’VE GOT API DEVELOPMENT AND MANUFACTURING DOWN TO AN EXACT SCIENCE API Commercial Product Catalogue PRODUCT CATALOGUE API Commercial US EU Japan US EU Japan API Name Site CEP India China API Name Site CEP India China DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF Rozzano Quinto de Adenosine Betaine Citrate Anhydrous Bon Encontre, France A Stampi, Italy • Betametasone-17,21- Alcaftadine Valladolid, Spain Valladolid, Spain • Dipropionate Sterile • Alclometasone-17,21- Valladolid, Spain Betamethasone Acetate Valladolid, Spain Dipropionate • • • Altrenogest Valladolid, Spain • • Betamethasone Base Valladolid, Spain Aminobisamide HCl Rensselaer, US Betamethasone Benzoate Valladolid, Spain Amphetamine Aspartate Betamethasone Valerate Rensselaer, US Valladolid, Spain Monohydrate Milled • Acetate Betamethasone-17,21- Amphetamine Sulfate Rensselaer, US Valladolid, Spain • Dipropionate • • • • Rozzano Quinto de Argatroban Betamethasone-17-Valerate Valladolid, Spain Stampi, Italy • • • • Betamethasone-21- Atenolol Aurangabad, India Valladolid, Spain • • • Phosphate Disodium Salt • • Rozzano Quinto de Bromfenac Monosodium Atracurium Besylate Lodi, Italy Stampi, Italy • Salt Sesquihydrate • • Rozzano Quinto de Atropine Sulfate Grafton, US Bromocriptine Mesylate • Stampi, Italy • • • Rozzano Quinto de Azelastine HCl Budesonide Valladolid, Spain Stampi, Italy • • • • • Rozzano Valleambrosia, Aztreonam (not sterile) Budesonide Sterile Valladolid, Spain Italy • • • • B Bamifylline HCl Bon Encontre, France • C Capecitabine Lodi, Italy • • Beclomethasone-17,21- Valladolid, Spain -

Minutes of PRAC Meeting on 28-31 October 2019

28 November 2019 EMA/PRAC/107813/2020 Inspections, Human Medicines Pharmacovigilance and Committees Division Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) Minutes of PRAC meeting on 28 – 31 October 2019 Chair: Sabine Straus – Vice-Chair: Martin Huber Health and safety information In accordance with the Agency’s health and safety policy, delegates were briefed on health, safety and emergency information and procedures prior to the start of the meeting. Disclaimers Some of the information contained in the minutes is considered commercially confidential or sensitive and therefore not disclosed. With regard to intended therapeutic indications or procedure scope listed against products, it must be noted that these may not reflect the full wording proposed by applicants and may also change during the course of the review. Additional details on some of these procedures will be published in the PRAC meeting highlights once the procedures are finalised. Of note, the minutes are a working document primarily designed for PRAC members and the work the Committee undertakes. Note on access to documents Some documents mentioned in the minutes cannot be released at present following a request for access to documents within the framework of Regulation (EC) No 1049/2001 as they are subject to on- going procedures for which a final decision has not yet been adopted. They will become public when adopted or considered public according to the principles stated in the Agency policy on access to documents (EMA/127362/2006, Rev. 1). Official address Domenico Scarlattilaan 6 ● 1083 HS Amsterdam ● The Netherlands Address for visits and deliveries Refer to www.ema.europa.eu/how-to-find-us Send us a question Go to www.ema.europa.eu/contact Telephone +31 (0)88 781 6000 An agency of the European Union © European Medicines Agency, 2020. -

New Approaches to the Treatment of Opioid-Induced Constipation

European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2008; 12(Suppl 1): 119-127 New approaches to the treatment of opioid-induced constipation P. HOLZER Research Unit of Translational Neurogastroenterology, Institute of Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Graz, Graz (Austria) Abstract. – Opiates are indispensable Introduction for the treatment of moderate to severe pain. The gastrointestinal tract is one of the major Opium derived from the unripe seed capsules victims of the undesired effects of opiates, be- cause the enteric nervous system expresses of Papaver somniferum has been used since an- all major subtypes of opioid receptors. As a cient times to treat diarrhoea. We now know that result, propulsive motility and secretory the biological effects of opium are due not only processes in the gut are inhibited by opioid to morphine and codeine but also other drugs analgesics, and the ensuing constipation is such as papaverine, all of which affect the func- one of the most frequent and troublesome ad- tion of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Despite verse reactions. Many treatments involving laxatives, prokinetic drugs and opioid-sparing many attempts to develop other strong pain ther- regimens have been explored to circumvent apeutics, opioid analgesics have remained the opioid-induced bowel dysfunction, but the mainstay of therapy in many patients with mod- outcome has in general been unsatisfactory. erate to severe pain. However, the use of opioid Specific antagonism of peripheral opioid re- analgesics is associated with a number of adverse ceptors offers a more rational approach to the effects among which those on the GI tract are management of the adverse actions of opioid most troublesome in terms of frequency and analgesics in the gut. -

208271Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 208271Orig1s000 OTHER REVIEW(S) Reference ID: 3963792 Reference ID: 3963792 Reference ID: 3963792 Reference ID: 3963792 Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Office of Medical Policy PATIENT LABELING REVIEW Date: June 22, 2016 To: Donna Griebel, MD Director Division of Gastroenterology and Inborn Errors Products (DGIEP) Through: LaShawn Griffiths, MSHS-PH, BSN, RN Associate Director for Patient Labeling Division of Medical Policy Programs (DMPP) Marcia Williams, PhD Team Leader, Patient Labeling Division of Medical Policy Programs (DMPP) From: Karen Dowdy, RN, BSN Patient Labeling Reviewer Division of Medical Policy Programs (DMPP) Meeta Patel, Pharm.D. Regulatory Review Officer Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP) Subject: Review of Patient Labeling: Medication Guide (MG) and Instructions for Use (IFU) Drug Name (established RELISTOR (methylnaltrexone bromide) name): Dosage Form and Route: tablets, for oral use injection, for subcutaneous use Application NDA 208271 Type/Number: Applicant: Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc., with its affiliate, Valeant Pharmaceutical North America being the communicant Reference ID: 3949385 1 INTRODUCTION On June 19, 2015, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc., with its affiliate, Valeant Pharmaceutical North America being the communicant, submitted for the Agency’s review 505(b)(1) New Drug Application (NDA) 208271 for RELISTOR (methylnaltrexone bromide) tablets. The proposed indication for RELISTOR tablets is for the treatment of opioid- induced constipation (OIC) in adult patients with chronic non-cancer pain. The Applicant cross-references all data contained in RELISTOR Subcutaneous Injection NDA 021964/S-010 approved for the treatment of OIC in adult patients with chronic non-cancer pain on September 29, 2014. -

Naldemedine (Symproic) for the Treatment of Opioid-Induced Constipation Kenneth Hu, Pharmd; and Mary Barna Bridgeman, Pharmd, BCPS, BCGP

DRUG FORECAST Naldemedine (Symproic) for the Treatment Of Opioid-Induced Constipation Kenneth Hu, PharmD; and Mary Barna Bridgeman, PharmD, BCPS, BCGP INTRODUCTION as less severe, but potentially bother- (FDA) in March of 2017 for the treatment Pain, pain management, and the com- some, and can ultimately contribute to of OIC in adult patients with chronic non- plications associated with interventions non-compliance with the prescribed regi- cancer pain.9 intended to mitigate pain are associated men. In particular, gastrointestinal (GI) with signifi cant direct and indirect health side effects, including nausea, abdomi- PHARMACOLOGY care costs. Beyond the direct costs associ- nal pain, bloating, abdominal cramping, The mu (µ)-, delta (δ)-, and kappa ated with medications, hospitalizations, and constipation, can have an impact on (κ)-opioid receptors are common in provider visits, physical therapy, and the quality of life, dignity, and health of the central nervous system (CNS), but rehabilitation, chronic pain places an patients utilizing these agents for chronic they are also involved with GI function. enormous indirect burden on the affected pain management. Opioid-induced consti- While the δ- and κ-receptors are primarily individual’s productivity, quality of life, pation (OIC), new or worsening constipa- found in the proximal colon and stomach, and mental health. More than 100 mil- tion occurring when initiating, changing, the µ-receptors are widely distributed lion Americans are estimated to suffer or increasing opioid use, represents