Front Matter, the Service Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agricultural Structure in a Service Economy

LUTHER TWEETEN Agricultural Structure in a Service Economy INTRODUCTION Highly developed market economies have been described variously as affluent, technocratic, and urban-industrial (see Ruttan 1969; Tweeten 1979, cbs. 1, 2). Such economies may also be characterised by service economies because a large portion of jobs are in service industries, such as, trade, finance, insurance, and government (see Table 1). Approxi mately three out of five jobs in the United States were in service industries in 1982. If service jobs in transportation, communications and public utilities are included, then nearly two out of three jobs were in service industries. Perhaps more important, as many as nine out of ten new jobs were in service industries. Non-metropolitan counties (essen tially those not having a city of 50,000 or more) did not differ sharply in structure from metropolitan communities; the major difference was relatively lower employment in service industries and higher employment in extractive (agriculture and mining) industries in non-metropolitan counties (Table 1). As buying power expands, consumers seek self-fulfilment and self-realisation as opposed to simply meeting basic needs for food, shelter and clothing. Income elasticities tend to be high for entertainment, health care, education, eating out, finance and insurance. Thus, normal workings of the price system cause advanced market economies to become service economies. The thesis of this paper is that transformation of nations into post-industrial service economies has pervasive implica tions for agriculture and rural communities. A number of such implications are explored herein. SERVICE INDUSTRIES Service industries and servcie employment are too diverse to be easily classified. -

The Great Divergence the Princeton Economic History

THE GREAT DIVERGENCE THE PRINCETON ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE WESTERN WORLD Joel Mokyr, Editor Growth in a Traditional Society: The French Countryside, 1450–1815, by Philip T. Hoffman The Vanishing Irish: Households, Migration, and the Rural Economy in Ireland, 1850–1914, by Timothy W. Guinnane Black ’47 and Beyond: The Great Irish Famine in History, Economy, and Memory, by Cormac k Gráda The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy, by Kenneth Pomeranz THE GREAT DIVERGENCE CHINA, EUROPE, AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD ECONOMY Kenneth Pomeranz PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD COPYRIGHT 2000 BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 41 WILLIAM STREET, PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 08540 IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 3 MARKET PLACE, WOODSTOCK, OXFORDSHIRE OX20 1SY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA POMERANZ, KENNETH THE GREAT DIVERGENCE : CHINA, EUROPE, AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD ECONOMY / KENNETH POMERANZ. P. CM. — (THE PRINCETON ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE WESTERN WORLD) INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES AND INDEX. ISBN 0-691-00543-5 (CL : ALK. PAPER) 1. EUROPE—ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—18TH CENTURY. 2. EUROPE—ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—19TH CENTURY. 3. CHINA— ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—1644–1912. 4. ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT—HISTORY. 5. COMPARATIVE ECONOMICS. I. TITLE. II. SERIES. HC240.P5965 2000 337—DC21 99-27681 THIS BOOK HAS BEEN COMPOSED IN TIMES ROMAN THE PAPER USED IN THIS PUBLICATION MEETS THE MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS OF ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (PERMANENCE OF PAPER) WWW.PUP.PRINCETON.EDU PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 3579108642 Disclaimer: Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. -

The First Great Divergence

Mellon-Sawyer Seminar 2007/8 “The first great divergence: China and Europe, 500-800 CE” Organized by Ian Morris, Walter Scheidel, and Mark Lewis, Departments of Classics and History, Stanford University Sponsored by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Six hundred years ago China was the most powerful state on earth. The eunuch admiral Zheng He spent 1406 cruising around the Indian Ocean at the head of 30,000 crew in a fleet of giant Chinese “treasure ships,” trading, collecting tribute, and setting up and deposing client kings at will. By 1433, Chinese ships were visiting Arabia, Ethiopia, and Kenya, and probably Australia too. By any reasonable estimate, China seemed set to become the world’s first global power. But that did not happen. Anti-trade Confucian factions won out in struggles at the Ming court, and long-distance voyages were banned. By 1467, most records of Zheng’s voyages were lost or destroyed. Half a millennium later, far from dominating as the world, China seemed – at least to western observers – to be going backward. When a dispute over opium trading escalated uncontrollably in 1839, the British sent a small naval force to claim damages from the governor of Canton. A single ironclad gunboat blasted its way through all the Chinese defenses, and in 1842, with the Grand Canal under British control, Nanjing facing plunder, and famine closing in on Beijing, China conceded British demands for open ports and the right to send missionaries deep into the country. This defeat triggered crises that brought China to the verge of partition. One Hong Xiuquan, a failed civil service candidate who developed his own bizarre version of Christianity out of the teachings of the missionaries at Canton, led the massive Taiping Rebellion to install a Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace. -

The 4 Economic Systems What Is an Economic System?

The 4 Economic Systems What is an Economic System? Economics is the study of how people make decisions given the resources that are provided to them Economics is all about CHOICES, both individual and group choices. We must make choices to provide for our needs and wants. The choices each society or nation selects leads to the creation of their type of economy. 3 Basic Questions Each economic system tries to answer the three basic questions: What should be produced? How it should be produced? For whom should it be produced? How they answer these questions determines the kind of system they have. Four Types of Systems There are four main types of economic systems. The Traditional Economic System The Command Economic System The Market Economic System The Mixed Economic System Each system has its strengths and weaknesses. Traditional Economy In a traditional economy, the customs and habits of the past are used to decide what and how goods will be produced, distributed, and consumed. Each member of society knows from early on what their role in the larger group will be. Jobs are passed down from generation to generation so there is little change in jobs over the generations. In a traditional economy, people are depended upon to fulfill their jobs. If someone fails to do their part, the system can break down. Farming, hunting, and herding are part of a traditional economy. Traditional economies can be found in different indigenous groups. In addition, traditional economies bartering is used for trade. Bartering is trading without money. For example, if an individual has a good and he trades it with another individual for a different good. -

Notes on Structural Change and Economic Development Vivianne

ISSN 2222-4815 A service-based economy: where do we stand? Notes on structural change and economic development Vivianne Ventura-Dias WorkingPaper # 139 | Septiembre 2011 A service-based economy: where do we stand? Notes on structural change and economic development Vivianne Ventura-Dias LATN – Latin American Trade Network ([email protected]) Abstract The purpose of this paper is to provide a comprehensive view of the state of the art of economic research on services and the service economy and thereby contribute to the discussion of a model of inclusive and sustainable development in Latin America. The economic literature on services is widely dispersed in different academic fields that study services, namely economics, marketing, urban and regional studies, geography, human resources and operations research, with very little exchange between these disciplines than it is desired. Although the literature covered much of the empirical ground, it still proposes more questions than answers on macro and micro issues related to growth, employment and productivity in service-based economies. The paper is divided into five sections, including this introduction. Next section is focused on two aspects of the services debate: (i) the definition and measurement of services; and (ii) the determinants of growth of services. Section 3 discusses new trends in international trade that gave prominence to the formation of international supply chains through widespread outsourcing. Section 4 proposes a discussion on the role of services in Latin American -

The Basic Economics of Internet Infrastructure

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 34, Number 2—Spring 2020—Pages 192–214 The Basic Economics of Internet Infrastructure Shane Greenstein his internet barely existed in a commercial sense 25 years ago. In the mid- 1990s, when the data packets travelled to users over dial-up, the main internet T traffic consisted of email, file transfer, and a few web applications. For such content, users typically could tolerate delays. Of course, the internet today is a vast and interconnected system of software applications and computing devices, which society uses to exchange information and services to support business, shopping, and leisure. Not only does data traffic for streaming, video, and gaming applications comprise the majority of traffic for internet service providers and reach users primarily through broadband lines, but typically those users would not tolerate delays in these applica- tions (for usage statistics, see Nevo, Turner, and Williams 2016; McManus et al. 2018; Huston 2017). In recent years, the rise of smartphones and Wi-Fi access has supported growth of an enormous range of new businesses in the “sharing economy” (like, Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb), in mobile information services (like, social media, ticketing, and messaging), and in many other applications. More than 80 percent of US households own at least one smartphone, rising from virtually zero in 2007 (available at the Pew Research Center 2019 Mobile Fact Sheet). More than 86 percent of homes with access to broadband internet employ some form of Wi-Fi for accessing applications (Internet and Television Association 2018). It seems likely that standard procedures for GDP accounting underestimate the output of the internet, including the output affiliated with “free” goods and the restructuring of economic activity wrought by changes in the composition of firms who use advertising (for discussion, see Nakamura, Samuels, and Soloveichik ■ Shane Greenstein is the Martin Marshall Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School, Boston, Massachusetts. -

The Neoliberal Rhetoric of Workforce Readiness

The Neoliberal Rhetoric of Workforce Readiness Richard D. Lakes Georgia State University, Atlanta, USA Abstract In this essay I review an important report on school reform, published in 2007 by the National Center on Education and the Economy, and written by a group of twenty-five panelists in the USA from industry, government, academia, education, and non-profit organizations, led by specialists in labor market economics, named the New Commission on the Skills of the American Workforce. These neoliberal commissioners desire a broad overhaul of public schooling, ending what is now a twelve-year high school curriculum after the tenth-grade with a series of state board qualifying exit examinations. In this plan vocational education (also known as career and technical education) has been eliminated altogether in the secondary-level schools as curricular tracks are consolidated into one, signifying a national trend of ratcheting-up prescribed academic competencies for students. I argue that college-for-all neoliberals valorize the middle-class values of individualism and self-reliance, entrepreneurship, and employment in the professions. Working-class students are expected to reinvent themselves in order to succeed in the new capitalist order. Imperatives in workforce readiness Elected officials in state and national legislatures and executive offices share a neoliberal perspective that public school students are academically deficient and under-prepared as future global workers. Their rhetoric has been used to re-establish the role of evidence-based measurement notably through report cards of student's grade-point-averages and test-taking results. Thus, states are tightening their diploma offerings and consolidating curricular track assignments. -

Ancient Economic Thought, Volume 1

ANCIENT ECONOMIC THOUGHT This collection explores the interrelationship between economic practice and intellectual constructs in a number of ancient cultures. Each chapter presents a new, richer understanding of the preoccupation of the ancients with specific economic problems including distribution, civic pride, management and uncertainty and how they were trying to resolve them. The research is based around the different artifacts and texts of the ancient East Indian, Hebraic, Greek, Hellenistic, Roman and emerging European cultures which remain for our consideration today: religious works, instruction manuals, literary and historical writings, epigrapha and legal documents. In looking at such items it becomes clear what a different exercise it is to look forward, from the earliest texts and artifacts of any culture, to measure the achievements of thinking in the areas of economics, than it is to take the more frequent route and look backward, beginning with the modern conception of economic systems and theory creation. Presenting fascinating insights into the economic thinking of ancient cultures, this volume will enhance the reawakening of interest in ancient economic history and thought. It will be of great interest to scholars of economic thought and the history of ideas. B.B.Price is Professor of Ancient and Medieval History at York University, Toronto, and is currently doing research and teaching as visiting professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ROUTLEDGE STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ECONOMICS 1 Economics as Literature -

The-Great-Depression-Glossary.Pdf

The Great Depression | Glossary of Terms Glossary of Terms Balanced budget – Government revenues equal expenditures on an annual basis. (Lesson 5) Bank failure – When a bank’s liabilities (mainly deposits) exceed the value of its assets. (Lesson 3) Bank panic – When a bank run begins at one bank and spreads to others, causing people to lose confidence in banks. (Lesson 3) Bank reserves – The sum of cash that banks hold in their vaults and the deposits they maintain with Federal Reserve banks. (Lesson 3) Bank run – When many depositors rush to the bank to withdraw their money at the same time. (Lesson 3) Bank suspensions – Comprises all banks closed to the public, either temporarily or permanently, by supervisory authorities or by the banks’ boards of directors because of financial difficulties. Banks that close under a special holiday declaration and remained closed only during the designated holiday are not counted as suspensions. (Lesson 4) Banks – Businesses that accept deposits and make loans. (Lesson 2) Budget deficit – When government expenditures exceed revenues. (Lesson 4) Budget surplus – When government revenues exceed expenditures. (Lesson 4) Consumer confidence – The relationship between how consumers feel about the economy and their spending and saving decisions. (Lesson 5) Consumer Price Index (CPI) – A measure of the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services. (Lesson 1) Deflation – A general downward movement of prices for goods and services in an economy. (Lessons 1, 3 and 6) Depression – A very severe recession; a period of severely declining economic activity spread across the economy (not limited to particular sectors or regions) normally visible in a decline in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, wholesale-retail credit and the loss of overall confidence in the economy. -

Employment Situation of Veterans — 2020

For release 10:00 a.m. (ET) Thursday, March 18, 2021 USDL-21-0438 Technical information: (202) 691-6378 • [email protected] • www.bls.gov/cps Media contact: (202) 691-5902 • [email protected] EMPLOYMENT SITUATION OF VETERANS — 2020 The unemployment rate for veterans who served on active duty in the U.S. Armed Forces at any time since September 2001—a group referred to as Gulf War-era II veterans—rose to 7.3 percent in 2020, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. The jobless rate for all veterans increased to 6.5 percent in 2020. These increases reflect the effect of the coronavirus (COVID- 19) pandemic on the labor market. In August 2020, 40 percent of Gulf War-era II veterans had a service-connected disability, compared with 26 percent of all veterans. This information was obtained from the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly sample survey of about 60,000 eligible households that provides data on employment, unemployment, and persons not in the labor force in the United States. Data about veterans are collected monthly in the CPS; these monthly data are the source of the 2020 annual averages presented in this news release. In August 2020, a supplement to the CPS collected additional information about veterans on topics such as service-connected disability and veterans' current or past Reserve or National Guard membership. Information from the supplement is also presented in this news release. The supplement was co-sponsored by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the U.S. Department of Labor's Veterans' Employment and Training Service. -

What Is Unemployment Insurance (Ui)? Am I Eligible? How Do I Apply?

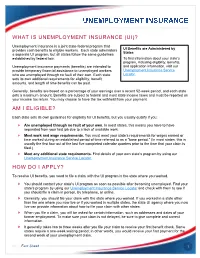

WHAT IS UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE (UI)? Unemployment Insurance is a joint state-federal program that provides cash benefits to eligible workers. Each state administers UI Benefits are Administered by States a separate UI program, but all states follow the same guidelines established by federal law. To find information about your state’s program, including eligibility, benefits, Unemployment insurance payments (benefits) are intended to and application information, visit our provide temporary financial assistance to unemployed workers Unemployment Insurance Service who are unemployed through no fault of their own. Each state Locator. sets its own additional requirements for eligibility, benefit amounts, and length of time benefits can be paid. Generally, benefits are based on a percentage of your earnings over a recent 52-week period, and each state sets a maximum amount. Benefits are subject to federal and most state income taxes and must be reported on your income tax return. You may choose to have the tax withheld from your payment. AM I ELIGIBLE? Each state sets its own guidelines for eligibility for UI benefits, but you usually qualify if you: Are unemployed through no fault of your own. In most states, this means you have to have separated from your last job due to a lack of available work. Meet work and wage requirements. You must meet your state’s requirements for wages earned or time worked during an established period of time referred to as a "base period." (In most states, this is usually the first four out of the last five completed calendar quarters prior to the time that your claim is filed.) Meet any additional state requirements. -

A Glossary of Fiscal Terms & Acronyms

AUGUST7,1998VOLUME13,NO .VII A Publication of the House Fiscal Analysis Department on Government Finance Issues A GLOSSARY OF FISCAL TERMS & ACRONYMS 1998 Revised Edition Abstract. This issue of Money Matters is a resource document containing terms and acronyms commonly used by and in legislative fiscal committees and in the discussion of state budget and tax issues. The first section contains terms and abbreviations used in all fiscal committees and divisions. The remaining sections contain terms for particular budget categories and accounts, organized according to fiscal subject areas. This edition has new sections containing economic development, family and early childhood, and housing terms and acronyms. The other sections are revised and updated to reflect changes in terminology, particularly the human services section. For further information, contact the Chief Fiscal Analyst or the fiscal analyst assigned to the respective House fiscal committee or division. A directory of House Fiscal Analysis Department personnel and their committee/division assignments for the 1998 legislative session appears on the next page. Originally issued January 1997 Revised August 1998 House Fiscal Analysis Department Staff Assignments — 1998 Session Committee/Division Fiscal Analyst Telephone Room Chief Fiscal Analyst Bill Marx 296-7176 373 Capital Investment John Walz 296-8236 376 EDIT— Economic Development Finance CJ Eisenbarth Hager 296-5813 428 EDIT— Housing Finance Cynthia Coronado 296-5384 361 Environment & Natural Resources Finance Jim Reinholdz 296-4119 370 Education — Higher Education Finance Doug Berg 296-5346 372 K-12 Education Finance Greg Crowe 296-7165 378 Family & Early Childhood Finance Cynthia Coronado 296-5384 361 Health & Human Services Finance Joe Flores 296-5483 385 Judiciary Finance Gary Karger 296-4181 383 State Government Finance Helen Roberts 296-4117 374 Transportation Finance John Walz 296-8236 376 Taxes — Income, sales, misc.