The Early Specimens of the Wandering Albatross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

MAGNIFICENT FRIGATEBIRD Fregata Magnificens

PALM BEACH DOLPHIN PROJECT FACT SHEET The Taras Oceanographic Foundation 5905 Stonewood Court - Jupiter, FL 33458 - (561-762-6473) [email protected] MAGNIFICENT FRIGATEBIRD Fregata magnificens CLASS: Aves ORDER: Suliformes FAMILY: Fregatidae GENUS: Fregata SPECIES: magnificens A long-winged, fork-tailed bird of tropical oceans, the Magnificent Frigatebird is an agile flier that snatches food off the surface of the ocean and steals food from other birds. It breeds mostly south of the United States, but wanders northward along the coasts during nonbreeding season. Physical Appearance: Frigate birds are the only seabirds where the male and female look strikingly different. All have pre- dominantly black plumage, long, deeply forked tails and long hooked bills. Females have white underbellies and males have a distinctive red throat pouch, which they inflate during the breeding season to attract females Their wings are long and pointed and can span up to 2.3 meters (7.5 ft), the largest wing area to body weight ratio of any bird. These birds are about 35-45 inches ((89 to 114 cm) in length, and weight between 35 and 67 oz (1000-1900 g). The bones of frigate birds are markedly pneumatic (filled with air), making them very light and contribute only 5% to total body weight. The pectoral girdle (shoulder joint) is strong as its bones are fused. Habitat: Frigate birds are found across all tropical oceans. Breeding habitats include mangrove cays on coral reefs, and decidu- ous trees and bushes on dry islands. Feeding range while breeding includes shallow water within lagoons, coral reefs, and deep ocean out of sight of land. -

Plumage and Sexual Maturation in the Great Frigatebird Fregata Minor in the Galapagos Islands

Valle et al.: The Great Frigatebird in the Galapagos Islands 51 PLUMAGE AND SEXUAL MATURATION IN THE GREAT FRIGATEBIRD FREGATA MINOR IN THE GALAPAGOS ISLANDS CARLOS A. VALLE1, TJITTE DE VRIES2 & CECILIA HERNÁNDEZ2 1Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Colegio de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, Campus Cumbayá, Jardines del Este y Avenida Interoceánica (Círculo de Cumbayá), PO Box 17–12–841, Quito, Ecuador ([email protected]) 2Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, PO Box 17–01–2184, Quito, Ecuador Received 6 September 2005, accepted 12 August 2006 SUMMARY VALLE, C.A., DE VRIES, T. & HERNÁNDEZ, C. 2006. Plumage and sexual maturation in the Great Frigatebird Fregata minor in the Galapagos Islands. Marine Ornithology 34: 51–59. The adaptive significance of distinctive immature plumages and protracted sexual and plumage maturation in birds remains controversial. This study aimed to establish the pattern of plumage maturation and the age at first breeding in the Great Frigatebird Fregata minor in the Galapagos Islands. We found that Great Frigatebirds attain full adult plumage at eight to nine years for females and 10 to 11 years for males and that they rarely attempted to breed before acquiring full adult plumage. The younger males succeeded only at attracting a mate, and males and females both bred at the age of nine years when their plumage was nearly completely adult. Although sexual maturity was reached as early as nine years, strong competition for nest-sites may further delay first reproduction. We discuss our findings in light of the several hypotheses for explaining delayed plumage maturation in birds, concluding that slow sexual and plumage maturation in the Great Frigatebird, and perhaps among all frigatebirds, may result from moult energetic constraints during the subadult stage. -

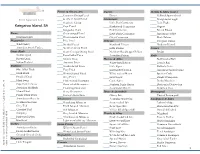

Bird Species Checklist

Petrels & Shearwaters Darters Hawks & Allies (cont.) Common Diving-Petrel Darter Collared Sparrowhawk Bird Species List Southern Giant Petrel Cormorants Wedge-tailed Eagle Southern Fulmar Little Pied Cormorant Little Eagle Kangaroo Island, SA Cape Petrel Black-faced Cormorant Osprey Kerguelen Petrel Pied Cormorant Brown Falcon Emus Great-winged Petrel Little Black Cormorant Australian Hobby Mainland Emu White-headed Petrel Great Cormorant Black Falcon Megapodes Blue Petrel Pelicans Peregrine Falcon Wild Turkey Mottled Petrel Fiordland Pelican Nankeen Kestrel Australian Brush Turkey Northern Giant Petrel Little Pelican Cranes Game Birds South Georgia Diving Petrel Northern Rockhopper Pelican Brolga Stubble Quail Broad-billed Prion Australian Pelican Rails Brown Quail Salvin's Prion Herons & Allies Buff-banded Rail Indian Peafowl Antarctic Prion White-faced Heron Lewin's Rail Wildfowl Slender-billed Prion Little Egret Baillon's Crake Blue-billed Duck Fairy Prion Eastern Reef Heron Australian Spotted Crake Musk Duck White-chinned Petrel White-necked Heron Spotless Crake Freckled Duck Grey Petrel Great Egret Purple Swamp-hen Black Swan Flesh-footed Shearwater Cattle Egret Dusky Moorhen Cape Barren Goose Short-tailed Shearwater Nankeen Night Heron Black-tailed Native-hen Australian Shelduck Fluttering Shearwater Australasian Bittern Common Coot Maned Duck Sooty Shearwater Ibises & Spoonbills Buttonquail Pacific Black Duck Hutton's Shearwater Glossy Ibis Painted Buttonquail Australasian Shoveler Albatrosses Australian White Ibis Sandpipers -

Wing and Primary Growth of the Wandering Albatross’

The Condor 101:360-368 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1999 WING AND PRIMARY GROWTH OF THE WANDERING ALBATROSS’ S. D. BERROW, N. HUN, R. HUMPIDGE, A. W. A. MURRAY AND I? A. PRINCE British Antarctic Survey,Natural EnvironmentalResearch Council, High Cross,Madingley Road, Cambridge, CB3 OET, UK, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. We investigatedthe relationshipbetween body mass and the rate and pattern of feather growth of the four outermost primaries of Wandering Albatross (Diomeden enu- lam) chicks. Maximum growth rates were similar (4.5 mm day-‘) for all feathers and be- tween sexes, although primaries of males were significantly longer than those of females. There was a distinctive pattern to primary growth with pl0 grown last, reaching its asymp- tote just prior to fledging. Primaries growing did so at different maximum rates; thus p7 reached its asymptote at an earlier age than p8 or p9, but maximum growth rates were the same for all primaries. Maximum growth rates of p7 and p8 were significantly correlated with chick mass at the start of the period of primary growth, and chick mass also was correlated with age at fledging. The heavier the chick, the earlier it grew its primaries and the younger it fledged. Fledging periods for Wandering Albatross chicks may be constrained by the time required to grow a full set of primaries. We suggest that the observed pattern of feather growth is a mechanism to minimize potential wear of the outer primaries prior to fledging. Key words: Diomedea exulans, growth rates, primaries, Wandering Albatross, wing growth. -

1. Check out Your Bird

1. Check out your bird ➢ Where are the feet placed on the body? Measure L Range of values: 47% Hawaiian Petrel (Procellariidae) to Common Murre 74% (Alcidae) 1. Check out your bird ➢ Where are the feet placed on the body? Measure L Range of values: 42% Chicken (Phasianidae) to Western Greebe 100% (Podicipedidae) 1. Check out your bird ➢ What are the feet like ? Write a brief description and make a drawing ➢ What is the tarsus like ? Write a brief description of the cross-section shape (Note: use calipers to measure tarsus cross-section) Tarsus Ratio = Parallel to leg movement Perpendicular to leg movement Round (Wood 1993) Elliptical Tarsus Tarsus 1. Check out your bird Tarsus Ratio = Parallel to leg movement Perpendicular to leg movement Range of values: Values < 1.00 1.00 Black-winged Petrel 0.80 RFBO (Procellariidae) (Sulidae) to to BRBO Common Murre (Sulidae) 1.50 (Alcidae) 0.80 Tarso-metatarsus Section Ratio (Wood 1993) Major and minor axes (a and b) of one tarsus per bird measured with vernier calipers at mid- point between ankle and knee. Cross-section ratio (a / b) reflects the extent to which tarsus is laterally compressed. Leg Position vs Tarsus Ratio 80 COMU 70 BRBO 60 Leg Position SOTEBOPE 50 RFBOBWPE GWGU (% Body Length)(% Body HAPE 40 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2.0 Tarsus Ratio 2. Make Bird Measurements ➢ Weight (to the closest gram): ➢ Lay out bird on its back and stretch the wings out. 2. Make Wing Measurements Wing Span = Wing Chord = Wing Aspect Ratio = Wing Loading = 2. -

Addo Elephant Birds

BIRDS OF THE ADDO ELEPHANT NATIONAL PARK An Addo Bird Checklist is a complex list as the park is made up of many sections of differing habitat. Be aware that a species on the cummulative list may be recorded from only one section, or may be cosmopolitan across several sections: Key to Status indicators : R = Resident; S = present in summer; W = present in winter; A = non-breeding visitor recorded throughout the year; V = Vagrant; ? - Uncertain status; c = common; u = uncommon; r = rare; l = localised English (Roberts 7) English (Roberts 6) Rob # Global Names Old SA Names Addo Elephant Combined Elephant Addo Gameand Main Camp Area - Section Inland Colchester - Section Coastal Colchester Waters and Islands Coastal Woody Cape Forest Alexandria Section Nyathi Zuurberg Section Section Kabouga Section Darlington Area Contractual Kuzuko 1Common Ostrich Ostrich 1Rc Rc RcRcRc 2King Penguin King Penguin 1 V 2.1Gentoo Penguin (925) Gentoo Penguin 1 V V V 3African Penguin Jackass Penguin 1 V Rc V 5Macaroni Penguin Macaroni Penguin 1 V V V 7 Black-necked Grebe Blacknecked Grebe 1 V V 8Little Grebe Dabchick 1 Rc V RcRc RcRcRcRcRc 10 Wandering Albatross Wandering Albatross 1 Au 11Shy Albatross Shy Albatross 1 Au 12 Black-Browed Albatross Blackbrowed Albatross 1 Ac 13 Grey-Headed Albatross Greyheaded Albatross 1 V 14 Atlantic Yellow-Nosed Albatross Yellownosed Albatross 1 Au 14.1 Indian Yellow-Nosed Albatross 1 Ac 15 Sooty Albatross Darkmantled Sooty Albatross 1 V 16 Light-mantled Albatross Lightmantled Sooty Albatross 1 V 17 Southern Giant-Petrel Southern -

Analysis of Albatross and Petrel Distribution Within the CCAMLR Convention Area: Results from the Global Procellariiform Tracking Database

CCAMLR Science, Vol. 13 (2006): 143–174 ANALYSIS OF ALBATROSS AND PETREL DISTRIBUTION WITHIN THE CCAMLR CONVENTION AREA: RESULTS FROM THE GLOBAL PROCELLARIIFORM TRACKING DATABASE BirdLife International (prepared by C. Small and F. Taylor) Wellbrook Court, Girton Road Cambridge CB3 0NA United Kingdom Correspondence address: BirdLife Global Seabird Programme c/o Royal Society for the Protection of Birds The Lodge, Sandy Bedfordshire SG19 2DL United Kingdom Email – [email protected] Abstract CCAMLR has implemented successful measures to reduce the incidental mortality of seabirds in most of the fisheries within its jurisdiction, and has done so through area- specific risk assessments linked to mandatory use of measures to reduce or eliminate incidental mortality, as well as through measures aimed at reducing illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. This paper presents an analysis of the distribution of albatrosses and petrels in the CCAMLR Convention Area to inform the CCAMLR risk- assessment process. Albatross and petrel distribution is analysed in terms of its division into FAO areas, subareas, divisions and subdivisions, based on remote-tracking data contributed to the Global Procellariiform Tracking Database by multiple data holders. The results highlight the importance of the Convention Area, particularly for breeding populations of wandering, grey-headed, light-mantled, black-browed and sooty albatross, and populations of northern and southern giant petrel, white-chinned petrel and short- tailed shearwater. Overall, the subareas with the highest proportion of albatross and petrel breeding distribution were Subareas 48.3 and 58.6, adjacent to the southwest Atlantic Ocean and southwest Indian Ocean, but albatross and petrel breeding ranges extend across the majority of the Convention Area. -

How Big Are Your Wings (PDF)

How Big Are Your Wings? 10/03/2006 12:26 PM Return to Activities Home Page HOW BIG ARE YOUR WINGS? Appropriate grade level: 4-6 Subjects: Science, Art Time required: 1-2 class periods Hawai’i Performance Standards: 1. Identify similarities and differences of organisms. 2. Describe differences in physical and behavioral traits that contribute to the survival of a particular living thing. 3. Describe motion in reference to space and time. Materials: Background information, roll of butcher paper, paints of various colors (white, black, gray, red, blue, pink, brown, tan, yellow), scissors, tape, measuring tape (centimeters), pencils Procedure: 1. Print a copy of bird wing anatomy from the website. Photocopy and pass out to students or make a poster size copy of the information to show the class. 2. Discuss different parts of a bird wing and compare it to our own arms. Differences include hollow/dense bone structure, feathers/skin, weight, the necessity for gathering food, metabolism, and heart rate. 3. Discussion ideas: Define adaptation. Questions to ask might include: Why don’t we fly and seabirds do? Do we need to fly to get our food? Why did birds develop this adaptation and we didn’t? 4. Art activity: Compare your own "wings" to the wings of the Laysan albatross and other seabirds. Print a copy of the silhouettes of various seabirds from the website. Using measuring tape, tape, butcher paper, pencils, and imagination, have students draw the silhouette of a Laysan albatross, wandering albatross, and great frigatebird. Students can draw the albatross "eyeshadow" and other markings of the birds with paints or other materials using the pictures and descriptions in this activity. -

Download 2019 Cruise Route Species Seen List As

Cruise: New Zealand, the Tasman Sea and Australia 2019 Route - Species Seen List Column A: number of past tours (out of 1) species has been seen Column B: Number of days this species was seen on the 2019-2020 tour Column C: The maximum daily count for this species on the 2019-2020 tour Column D: NX = Auckland, NZ extension; AX = Sydney, AUS extension A B C D 1 North Island Brown Kiwi 1 4 NX Apteryx mantelli 1 Australian Brushturkey 1 2 AX Alectura lathami 1 Magpie Goose 1 95 AX Anseranas semipalmata 1 Canada Goose 6 75 Branta canadensis 1 Musk Duck 1 8 Biziura lobata 1 Freckled Duck 1 8 Stictonetta naevosa 1 Cape Barren Goose 1 16 Cereopsis novaehollandiae 1 Black Swan 9 375 Cygnus atratus 1 Blue Duck 1 5 Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos 1 Australian Shelduck 1 27K Tadorna tadornoides 1 Paradise Shelduck 5 72 Tadorna variegata 1 Australian Wood Duck 6 70 Chenonetta jubata 1 Pink-eared Duck 1 4500 Malacorhynchus membranaceus 1 Australasian Shoveler 3 280 Anas rhynchotis 1 Grey Teal 6 550 Anas gracilis 1 Chestnut Teal 5 500 Anas castanea 1 Brown Teal 4 2 Anas chlorotis 1 Pacific Black Duck 8 140 Anas superciliosa 1 Mallard 6 52 Anas platyrhynchos 1 New Zealand Scaup 4 120 Aythya novaeseelandiae 1 Hardhead 4 450 Aythya australis 1 Blue-billed Duck 1 400 Oxyura australis 1 California Quail 3 5 Callipepla californica 1 Wild Turkey 2 2 Meleagris gallopavo 1 Ring-necked Pheasant 1 6 NX Phasianus colchicus 1 Brown Quail 3 3 Coturnix ypsilophora 1 Australasian Grebe 3 4 Tachybaptus novaehollandiae 1 New Zealand Grebe 4 4 Poliocephalus rufopectus 1 Hoary-headed Grebe 2 400 Poliocephalus poliocephalus 1 Great Crested Grebe 1 1 Podiceps cristatus ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. -

Wandering Albatross in California

502 GeneralNotes [Auk, Vol. 85 Wandering Albatross in California.--A WanderingAlbatross, Diomedea exuIans, was discoveredby residentsof The Sea Ranch, Sonoma County, California, about 60 miles north of San Francisco,in the late afternoon of 11 July 1967. It remainedin a field overlooking the sea overnight until the wind freshenedin the afternoon of 12 July, when it "stretchedits great wings,waddled into the wind, and took off over the bluff and out to sea" (Mrs. William E. Rand, pers. comm.). It was not seenagain. This appears to be the first record of this speciesin the Pacific Ocean north of Panamir, and the first record for North America. Although no professionalornithologist or person familiar with this speciessaw the bird in the flesh, it was photographedby several persons,notably Louis McLane, resident architect of The Sea Ranch, and Mr. and Mrs. Rex Hardy of Los Altos, California. Mrs. Hardy and Mrs. William E. Rand of San Franciscoprepared written statementsof their observationsof the bird. Photographs(Figure 1) have subsequently beenexamined by John W. Aldrich,J.P. Angle,George E. Watson,III, and Alexander Wetmore at the SmithsonianInstitution, and by EugeneEisenmann and Robert Cush- man Murphy of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. There seemsto be no doubt about the bird's identification. Its size and the pattern of featberingabout the baseof the mandiblesexclude all but the WanderingAlbatross and the Royal Albatross,Diomedea epomophora.In only these two speciesof alba- tross does feathering extend out over the base of the lower mandible as far as the nostril. The Royal Albatross,in turn, is excludedby a number of other features: the ovoid rather than larger round nasal openings,the vermiculated back• the large amount of black on the upper wing surfacesrelieved only by some white on the secondary coverts, the black crown and tail tip, and the absenceof a dark line along the cutting edge of the mandibles. -

Antipodean Wandering Albatross Census and Population Study 2018

Antipodean wandering albatross census and population study 2018 Graeme Elliott and Kath Walker August 2018 Antipodean wandering albatross 2018 ABSTRACT Antipodean wandering albatross Diomedea antipodensis antipodensis breed almost exclusively on Antipodes Island and following a dramatic population crash in 2006, males have been declining at about 6% per annum and females at about 12% per annum. The decline appears to be driven mainly by high female mortality, with a marked sex imbalance now conspicuous in the breeding population. There is a significant negative relationship between La Nina conditions (which bring warmer sea temperatures to the western Pacific) and the survival of breeding female Antipodean wandering albatrosses. However, while breeding success dropped from a mean 74% prior to the crash to 60% after it, poor nutrition of breeding females in La Nina summers appears unlikely to be the proximate cause of their high mortality as birds usually abandon breeding if their condition is too poor. The main preventable cause of high female mortality is likely to be fisheries bycatch north of New Zealand and in the central and eastern Pacific between 20-35°S, occurring in late winter and spring. Antipodean wandering albatross are now assessed by the New Zealand Threat Classification System as “Nationally Critical” (Robertson et al 2017) and understanding the causes of and solutions to the high female mortality is urgently required. Extensive real-time satellite tracking should be used to better define problems the birds are encountering at sea. INTRODUCTION Antipodean wandering albatross (Diomedea antipodensis antipodensis) are endemic to the Antipodes Islands, with approximately 99% of the population breeding there and a few pairs nesting on both Campbell Island and at the Chatham Islands.