Foraging Strategy of Wandering Albatrosses Through the Breeding Season: a Study Using Satellite Telemetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

MAGNIFICENT FRIGATEBIRD Fregata Magnificens

PALM BEACH DOLPHIN PROJECT FACT SHEET The Taras Oceanographic Foundation 5905 Stonewood Court - Jupiter, FL 33458 - (561-762-6473) [email protected] MAGNIFICENT FRIGATEBIRD Fregata magnificens CLASS: Aves ORDER: Suliformes FAMILY: Fregatidae GENUS: Fregata SPECIES: magnificens A long-winged, fork-tailed bird of tropical oceans, the Magnificent Frigatebird is an agile flier that snatches food off the surface of the ocean and steals food from other birds. It breeds mostly south of the United States, but wanders northward along the coasts during nonbreeding season. Physical Appearance: Frigate birds are the only seabirds where the male and female look strikingly different. All have pre- dominantly black plumage, long, deeply forked tails and long hooked bills. Females have white underbellies and males have a distinctive red throat pouch, which they inflate during the breeding season to attract females Their wings are long and pointed and can span up to 2.3 meters (7.5 ft), the largest wing area to body weight ratio of any bird. These birds are about 35-45 inches ((89 to 114 cm) in length, and weight between 35 and 67 oz (1000-1900 g). The bones of frigate birds are markedly pneumatic (filled with air), making them very light and contribute only 5% to total body weight. The pectoral girdle (shoulder joint) is strong as its bones are fused. Habitat: Frigate birds are found across all tropical oceans. Breeding habitats include mangrove cays on coral reefs, and decidu- ous trees and bushes on dry islands. Feeding range while breeding includes shallow water within lagoons, coral reefs, and deep ocean out of sight of land. -

The Winter Diet of the Great-Winged Petrel Pterodroma Macroptera at Sub-Antarctic Marion Island in 1991

Cooper & Klages: Winter diet of the Great-winged Petrel 261 THE WINTER DIET OF THE GREAT-WINGED PETREL PTERODROMA MACROPTERA AT SUB-ANTARCTIC MARION ISLAND IN 1991 JOHN COOPER1 & NORBERT T.W. KLAGES2 1Animal Demography Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa ([email protected]) 253 Clarendon Street, Mount Pleasant, Port Elizabeth, 6070, South Africa Received 11 June 2008, accepted 24 December 2008 SUMMARY COOPER, J. & KLAGES, N.T.W. 2009. The winter diet of the Great-winged Petrel Pterodroma macroptera at sub-Antarctic Marion Island in 1991. Marine Ornithology 37: 261–263. The diet of winter-breeding Great-winged Petrels Pterodroma macroptera was studied at sub-Antarctic Marion Island, Prince Edward Islands, southern Indian Ocean in August–October 1991 by multiple stomach flushing of weighed chicks after parental feeding. The Great-winged Petrel at Marion Island may be described as a cephalopod specialist, because squid formed the larger part of the diet in terms of diversity, frequency of occurrence and contribution by mass, and were the largest prey items taken. Fish and crustaceans formed relatively minor parts of the diet. These findings are broadly in accord with those of three previous quantitative studies at the same and other localities. Key words: Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera, cephalopods, Marion Island, diet INTRODUCTION visited at irregular intervals in the evenings and later at night, and any chicks that had gained at least 10 g because of a parental feed Seabirds are important “top predators” in the Southern Ocean, and over this time period were subjected to multiple stomach-flushing. -

Relative Passage Rates of Lipid and Aqueous Digesta in the Formation of Stomach Oils

RELATIVE PASSAGE RATES OF LIPID AND AQUEOUS DIGESTA IN THE FORMATION OF STOMACH OILS DANIEL D. ROBY,• KAREN L. BRINK,2 AND ALLEN R. PLACE3 •CooperativeWildlife Research Laboratory and Department of Zoology, SouthernIllinois University, Carbondale, Illinois 62901 USA, 2P.O. Box 571, Carbondale,Illinois 62903 USA, and 3Centerof MarineBiotechnology, University of Maryland,Baltimore, Maryland 21202 USA ABSTRACT.--Weused tritium-labeled glycerol triether as a nonabsorbablelipid-phase mark- er and carbon-14labeled polyethylene glycol as a nonabsorbableaqueous-phase marker to examine gastrointestinaltransit of a homogenized fish meal fed to 4-week-old chicks of AntarcticGiant-Petrels (Macronectes giganteus) and GentooPenguins (Pygoscelis papua). Both aqueous-phaseand lipid-phase markers passedthrough the gastrointestinaltract without being metabolized.Label recoveries from the two specieswere statisticallyindistinguishable. Mean retention time was significantlylonger for lipid-phasecomponents than for aqueous- phasecomponents in both species.In the petrel, mean retention time for lipid-phaseand for aqueous-phasewas significantlylonger than in the penguin. Interspecificdifferences in retention were largely the result of differing ratesof gastricemptying. Both markersemptied rapidly from the proventriculusand gizzard of the penguins,while in giant-petrelsthe lipid- phase was retained for extended periods in the stomach.Differential transit of lipid and aqueousphases coupled with the lower rate of gastricemptying in giant-petrelchicks provides a physiologicalbasis for accumulationof dietary lipids in the proventriculus. The large, distensibleproventriculus and the ventral positionof the pyloric valve relative to the gizzard and proventriculusare morphologicaltraits which enhance the formation and retention of stomachoils. Received31 May 1988,accepted 19 December1988. OFall avian internal organs,the range of mor- (Matthews 1949, Duke et al. 1989). In other birds phologicalvariation in the stomachis the great- the much smaller proventriculus is cranial to est. -

Plumage and Sexual Maturation in the Great Frigatebird Fregata Minor in the Galapagos Islands

Valle et al.: The Great Frigatebird in the Galapagos Islands 51 PLUMAGE AND SEXUAL MATURATION IN THE GREAT FRIGATEBIRD FREGATA MINOR IN THE GALAPAGOS ISLANDS CARLOS A. VALLE1, TJITTE DE VRIES2 & CECILIA HERNÁNDEZ2 1Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Colegio de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, Campus Cumbayá, Jardines del Este y Avenida Interoceánica (Círculo de Cumbayá), PO Box 17–12–841, Quito, Ecuador ([email protected]) 2Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, PO Box 17–01–2184, Quito, Ecuador Received 6 September 2005, accepted 12 August 2006 SUMMARY VALLE, C.A., DE VRIES, T. & HERNÁNDEZ, C. 2006. Plumage and sexual maturation in the Great Frigatebird Fregata minor in the Galapagos Islands. Marine Ornithology 34: 51–59. The adaptive significance of distinctive immature plumages and protracted sexual and plumage maturation in birds remains controversial. This study aimed to establish the pattern of plumage maturation and the age at first breeding in the Great Frigatebird Fregata minor in the Galapagos Islands. We found that Great Frigatebirds attain full adult plumage at eight to nine years for females and 10 to 11 years for males and that they rarely attempted to breed before acquiring full adult plumage. The younger males succeeded only at attracting a mate, and males and females both bred at the age of nine years when their plumage was nearly completely adult. Although sexual maturity was reached as early as nine years, strong competition for nest-sites may further delay first reproduction. We discuss our findings in light of the several hypotheses for explaining delayed plumage maturation in birds, concluding that slow sexual and plumage maturation in the Great Frigatebird, and perhaps among all frigatebirds, may result from moult energetic constraints during the subadult stage. -

Feeding Ecology of Short-Tailed Shearwaters: Breeding in Tasmania and Foraging in the Antarctic?

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published June 18 Mar Ecol Prog Ser l Feeding ecology of short-tailed shearwaters: breeding in Tasmania and foraging in the Antarctic? Henri Weimerskirch*, Yves Cherel CEBC - CNRS, F-79360 Beauvoir, France ABSTRACT- The food, feedlng and physiological ecology of foraging were studied in the short-tailed shearwater Puffinus tenujrostris of Tasmania, to establish whether this species can rely on Antarctic food to fledge its chick. Parents were found to use a 2-fold foraging strategy, on average performing 2 successive short trips at sea of 1 to 2 d duration followed by 1 long trip of 9 to 17 d. These long foraging tnps are the longest yet recorded for any seabird. During short trips the parents tend to lose mass, feed- ing the chick with Australian krill and fish larvae caught in coastal and neritic waters around Tasma- nia. The prey are caught at maximum diving depths of 13 m on average (maximum 30 m).During long trips, adults gain mass and feed their chlcks with a very rich mixture of stomach oil and digested food composed of a high diversity of prey including myctophid fish, sub-Antarctic krill and squids. Prey are probably caught mainly in the Polar Frontal Zone, at least 1000 km south of Tasmania, at maximum depths of 58 m on average (maximum 71 m). Long foraging trips in distant southern waters gave at least twice the yield of trips in close waters but during the former, yield decreased with the time spent for- aging, as indicated by the inverse relationship between time spent forag~ngand adult body condition. -

Large Pelagic Seabirds: Picture of Bird

Large Pelagic seabirds: Picture Albatrosses, Mollymawks & Giant Petrels of bird For idenDficaon and species info refer to: www.nzbirdsonline.org.nz Introduc4on Ecology and life history New Zealand has the highest diversity of Normal adult weight range: Adult Buller’s mollymawks can weigh as albatrosses and mollymawks with 12 liNle as 2.5kg while the Southern Royal Albatross can weigh up to species that breed on NZ's sub-antarcDc 10kg. Due to the variability of normal weight ranges between species islands and 7 endemic species. It is unlikely and within species it is recommended to calculate doses based on that large numbers of these birds would be individual body weights. effected during a single oil spill event Moult: Gradual, mostly during their non-breeding year but conDnues unless it occurs near a breeding colony. into breeding. Biennial wing moult - outer primaries one year, inner Although albatrosses are in the group primaries the next year. commonly called "tubenoses", they differ Breeding: All albatross species and the grey-headed mollymawk from other tubenose families in that their produce a single young every two years. Incubang and rearing a chick tube-shaped nostrils are separated and takes 1 year and then take one year to recover. located on either side of the bill. All birds The other mollymawk species and the two giant petrel species breed in the order Procellariformes (including once a year, usually from August to May. petrels and shearwaters) have three front- Lifespan: Long-lived facing toes with webbing. Diet: Water surface scavengers Personal protecve equipment (PPE): Appropriate PPE must be worn when capturing and handling oiled wildlife to prevent exposure to oil (disposable nitrile gloves, safety glasses/goggles, protecDon for clothing e.g. -

The Incidence, Functions and Ecological Significance of Petrel Stomach Oils

84 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NEW ZEALAND ECOLOGICAL SOCIETY, VOL. 24, 1977 THE INCIDENCE, FUNCTIONS AND ECOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF PETREL STOMACH OILS JOHN WARHAM Department of Zoology, University of Canterbury, Chrb;tchurch SUMMARY: Recent research into the origins and compositions of the stomach oils unique to sea~birds of the order Procellariifonnes is reviewed. The sources of these oils, most of which contain mainly wax esters and/or trigIycerides, is discussed in relation to the presence of such compounds in the marine environment. A number of functions are proposed as the ecological roles of the oils, including their use as slowIy~mobilisable energy and water reserves for adults and chicks and as defensive weaponry for surface-nesting species. Suggestions are made for further research, particularly into physiological and nutritional aspects. INTRODUCTION their table, a balm for their wounds, and a medicine Birds of the Order Procellariiforrnes (albatrosses, for their distempers." In New Zealand, Travers and fuJmars, shearwaters and other petrels) are peculiar Travers (1873) described how the Chatham Island in being able to store oil in their large, glandular and Morioris held young petrels over their mouths and very distensible fore-guts or proventriculi.. All petrel allowed the oil to drain directly into them. In some spedes so far examined, with the significant excep- years the St Kildans exported part of thei.r oil har~ tion of the diving petrels, Fam. Pelecanoididae, have vest, as the Australian mutton-birders stilI do with been found to contain oil at various times. The oi.1 oil from the chicks of P. tenuirostris. This has been occurs in both adults and chicks, in breeders and used as a basis for sun~tan lotions, but most nowa- non~breeders, and in birds taken at sea and on land. -

Intra- and Inter-Annual Breeding Season Diet of Leach's Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma Leucorhoa) at a Colony in Southern Oregon

INTRA- AND INTER-ANNUAL BREEDING SEASON DIET OF LEACH'S STORM-PETREL (OCEANODROMA LEUCORHOA) AT A COLONY IN SOUTHERN OREGON by MICHELLE ANDRIESE SCHUITEMAN A THESIS Presented to the Department ofBiology and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofScience December 2006 11 "Intra- and Inter-annual Breeding Season Diet ofLeach's Storm-petrel (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) at a Colony in Southern Oregon" a thesis prepared by Michelle Andriese Schuiteman in partial fulfillment ofthe requirments for the Master ofScience degree in the Department ofBiology. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Date Committee in Charge: Dr Alan Shanks, Chair Dr. Jan Hodder Dr. William Sydeman Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School 111 © 2006 Michelle Schuiteman lV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Michelle Andriese Schuiteman for the degree of Master ofScience in the Department ofBiology to be taken December 2006 Title: INTRA- AND INTER-ANNUAL BREEDING SEASON DIET OF LEACH'S STORM-PETREL (OCEANODROMA LEUCORHOA) AT A COLONY IN SOUTHERN OREGON The oceanic habitat varies on multiple spatial and temporal scales. Aspects ofthe ecology oforganisms that utilize this habitat can, in certain cases, be used as indicators of ocean conditions. In this study, diet ofthe Leach's storm-petrel (Oceanodroma leucorhoa) is examined to determine ifevidence ofchanging ocean conditions can be found in the diet. Regurgitations were collected from the birds in order to describe diet. Euphausiids and fish composed 80 - 90% ofthe diet in both years, with composition of each diametrically different between years. Other items found in samples included . hyperiid and gammariid amphipods, cephalopods, plastic pieces and a new species of Cirolanid isopod. -

Bird Species Checklist

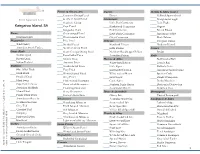

Petrels & Shearwaters Darters Hawks & Allies (cont.) Common Diving-Petrel Darter Collared Sparrowhawk Bird Species List Southern Giant Petrel Cormorants Wedge-tailed Eagle Southern Fulmar Little Pied Cormorant Little Eagle Kangaroo Island, SA Cape Petrel Black-faced Cormorant Osprey Kerguelen Petrel Pied Cormorant Brown Falcon Emus Great-winged Petrel Little Black Cormorant Australian Hobby Mainland Emu White-headed Petrel Great Cormorant Black Falcon Megapodes Blue Petrel Pelicans Peregrine Falcon Wild Turkey Mottled Petrel Fiordland Pelican Nankeen Kestrel Australian Brush Turkey Northern Giant Petrel Little Pelican Cranes Game Birds South Georgia Diving Petrel Northern Rockhopper Pelican Brolga Stubble Quail Broad-billed Prion Australian Pelican Rails Brown Quail Salvin's Prion Herons & Allies Buff-banded Rail Indian Peafowl Antarctic Prion White-faced Heron Lewin's Rail Wildfowl Slender-billed Prion Little Egret Baillon's Crake Blue-billed Duck Fairy Prion Eastern Reef Heron Australian Spotted Crake Musk Duck White-chinned Petrel White-necked Heron Spotless Crake Freckled Duck Grey Petrel Great Egret Purple Swamp-hen Black Swan Flesh-footed Shearwater Cattle Egret Dusky Moorhen Cape Barren Goose Short-tailed Shearwater Nankeen Night Heron Black-tailed Native-hen Australian Shelduck Fluttering Shearwater Australasian Bittern Common Coot Maned Duck Sooty Shearwater Ibises & Spoonbills Buttonquail Pacific Black Duck Hutton's Shearwater Glossy Ibis Painted Buttonquail Australasian Shoveler Albatrosses Australian White Ibis Sandpipers -

Wing and Primary Growth of the Wandering Albatross’

The Condor 101:360-368 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1999 WING AND PRIMARY GROWTH OF THE WANDERING ALBATROSS’ S. D. BERROW, N. HUN, R. HUMPIDGE, A. W. A. MURRAY AND I? A. PRINCE British Antarctic Survey,Natural EnvironmentalResearch Council, High Cross,Madingley Road, Cambridge, CB3 OET, UK, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. We investigatedthe relationshipbetween body mass and the rate and pattern of feather growth of the four outermost primaries of Wandering Albatross (Diomeden enu- lam) chicks. Maximum growth rates were similar (4.5 mm day-‘) for all feathers and be- tween sexes, although primaries of males were significantly longer than those of females. There was a distinctive pattern to primary growth with pl0 grown last, reaching its asymp- tote just prior to fledging. Primaries growing did so at different maximum rates; thus p7 reached its asymptote at an earlier age than p8 or p9, but maximum growth rates were the same for all primaries. Maximum growth rates of p7 and p8 were significantly correlated with chick mass at the start of the period of primary growth, and chick mass also was correlated with age at fledging. The heavier the chick, the earlier it grew its primaries and the younger it fledged. Fledging periods for Wandering Albatross chicks may be constrained by the time required to grow a full set of primaries. We suggest that the observed pattern of feather growth is a mechanism to minimize potential wear of the outer primaries prior to fledging. Key words: Diomedea exulans, growth rates, primaries, Wandering Albatross, wing growth. -

SYN Seabird Curricul

Seabirds 2017 Pribilof School District Auk Ecological Oregon State Seabird Youth Network Pribilof School District Ram Papish Consulting University National Park Service Thalassa US Fish and Wildlife Service Oikonos NORTAC PB i www.seabirdyouth.org Elementary/Middle School Curriculum Table of Contents INTRODUCTION . 1 CURRICULUM OVERVIEW . 3 LESSON ONE Seabird Basics . 6 Activity 1.1 Seabird Characteristics . 12 Activity 1.2 Seabird Groups . 20 Activity 1.3 Seabirds of the Pribilofs . 24 Activity 1.4 Seabird Fact Sheet . 26 LESSON TWO Seabird Feeding . 31 Worksheet 2.1 Seabird Feeding . 40 Worksheet 2.2 Catching Food . 42 Worksheet 2.3 Chick Feeding . 44 Worksheet 2.4 Puffin Chick Feeding . 46 LESSON THREE Seabird Breeding . 50 Worksheet 3.1 Seabird Nesting Habitats . .5 . 9 LESSON FOUR Seabird Conservation . 63 Worksheet 4.1 Rat Maze . 72 Worksheet 4.2 Northern Fulmar Threats . 74 Worksheet 4.3 Northern Fulmars and Bycatch . 76 Worksheet 4.4 Northern Fulmars Habitat and Fishing . 78 LESSON FIVE Seabird Cultural Importance . 80 Activity 5.1 Seabird Cultural Importance . 87 LESSON SIX Seabird Research Tools and Methods . 88 Activity 6.1 Seabird Measuring . 102 Activity 6.2 Seabird Monitoring . 108 LESSON SEVEN Seabirds as Marine Indicators . 113 APPENDIX I Glossary . 119 APPENDIX II Educational Standards . 121 APPENDIX III Resources . 123 APPENDIX IV Science Fair Project Ideas . 130 ii www.seabirdyouth.org 1 INTRODUCTION 2017 Seabirds SEABIRDS A seabird is a bird that spends most of its life at sea. Despite a diversity of species, seabirds share similar characteristics. They are all adapted for a life at sea and they all must come to land to lay their eggs and raise their chicks.