Oral History Interview with Angus Monroe and Lilly Monroe, Circa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Information TIPI Medicine Wheel TIPI Making Instructions Kit

TIPI Making Instructions Kit consist of: Cultural information 4 pony beads It is important to note that just like all traditional teachings, 1 long tie certain beliefs and values differ from region to region. 2 small ties 1 concho, 1 elastic 4 tipi posts TIPI 7 small sticks 1 round wood The floor of the tipi represents the earth on which we 1 bed, 1 note bag live, the walls represent the sky and the poles represent (with paper) the trails that extend from the earth to the spirit world (Dakota teachings). 1. Place tipi posts in holes (if needed use elastic to gather Tipis hold special significance among many different nations posts at top). and Aboriginal cultures across North America. They not only have cultural significance, but also serve practical purposes 2. Stick the double sided tape to the outside of the base (particularly when nations practiced traditional ways of (alternatively use glue or glue gun). living like hunting and gathering). Tipis provide shelter, warmth, and family and community connectedness. They 3. Stick the leather to the board, starting with the side are still used today for ceremonies and other purposes. without the door flap. Continue all the way around There is special meaning behind their creation and set up. (if needed cut the excess material). For spiritual purposes, the tipi’s entrance faces the East 4. Press all the way around a few times, to make sure the and the back faces the West. This is to symbolize the rising leather is well stuck onto the board. and setting of the sun and the cardinal directions. -

New Mexico New Mexico

NEW MEXICO NEWand MEXICO the PIMERIA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves NEW MEXICO AND THE PIMERÍA ALTA NEWand MEXICO thePI MERÍA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2017 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1-60732-573-4 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-60732-574-1 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Douglass, John G., 1968– editor. | Graves, William M., editor. Title: New Mexico and the Pimería Alta : the colonial period in the American Southwest / edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves. Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016044391| ISBN 9781607325734 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607325741 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spaniards—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. | Spaniards—Southwest, New—History. | Indians of North America—First contact with Europeans—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. -

Concrete Interstate Tipis of South Dakota (Constructed 1968-79) Meet the Criteria Consideration G Because of Their Exceptional Importance

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior Concrete Interstate TipisPut of South Here Dakota National Park Service Multiple Property Listing Name of Property National Register of Historic Places Multiple, South Dakota Continuation Sheet County and State Section number E Page 1 E. Statement of Historic Contexts NOTE: The terms “tipi,” “tepee,” and “teepee” are used interchangeably in both historical and popular documents. For consistency, the term “tipi” will be used in this document unless an alternate spelling is quoted directly. NOTE: The interstate tipis are not true tipis. They are concrete structures that imitate lodgepoles, or the lodgepoles framing the tipi structure. The lodgepoles interlock in a similar spiral fashion, as would a real tipi. An exact imitation of tipis would also have included smoke flap poles and covering. However, they have historically been referred to as tipis. This document will continue that tradition. List of Safety Rest Areas with Concrete Tipis in South Dakota Rest Area Location Year completed Comments (according to 1988 study) Spearfish: I-90 1977 Eastbound only Wasta: I-90 1968 Eastbound and Westbound Chamberlain: I-90 1976 Eastbound and West Salem: I-90 1968 East and Westbound Valley Springs (MN 1973 Eastbound only Border): I-90 Junction City 1979 Northbound and Southbound (Vermillion): I-29 Glacial Lakes (New 1978 Southbound only Effington): I-29 Introduction Between 1968 and 1979, nine concrete tipis were constructed at safety rest areas in South Dakota. Seven were constructed on Interstate 90 running east to west and two on Interstate 29 running north to south. -

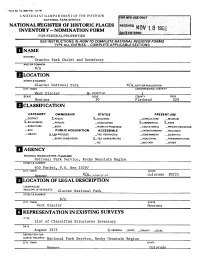

Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory AND/OR COMMON N/A LOCATION

Form No. i0-306 (Rev 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR lli|$|l;!tli:®pls NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES iliiiii: INVENTORY- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory AND/OR COMMON N/A LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Glacier National Park NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT West Glacier X- VICINITY OF 1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Montana 30 Flathead 029 QCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT X.PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X.COMMERCIAL X_RARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT N/AN PR OCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY _OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (Happlicable) ______National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Region STREET & NUMBER ____655 Parfet, P.O. Box 25287 CITY. TOWN STATE N/A _____Denver VICINITY OF Colorado 80225 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC Qlacier National STREET & NUMBER N/A CITY. TOWN STATE West Glacier Montana REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE List of Classified Structures Inventory DATE August 1975 X-FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Region CITY. TOWN STATE Colorado^ DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE X.GOOD —RUINS X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory are situated near the Swiftcurrent Pass in Glacier National Park at an elevation of 7,000 feet. -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Monument Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Classification of monument type records by function. -

NATIONAL REGISTER of HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM B

NFS Fbnn 10-900 'Oitntf* 024-0019 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service I * II b 1995 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM iNTERAGENCY RBOr- „ NATIONAL i3AR: 1. Name of Property fe NAllUNAL HhblbiLH d»vu,su historic name: Glacier National Park Tourist Trails: Inside Trail; South Circle; North Circle other name/site number Glacier National Park Circle Trails 2. Location street & number N/A not for publication: n/a vicinity: Glacier National Park (GLAC) city/town: N/A state: Montana code: MT county: Flathead; Glacier code: 29; 35 zip code: 59938 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1988, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant _ nationally X statewide _ locally. ( See continuation sheet for additional comments.) ) 9. STgnatuTBof 'certifying official/Title National Park Service State or Federal agency or bureau In my opinion, thejiuipKty. does not meet the National Register criteria. gj-^ 1B> 2 9 1995. Signature of commenting or other o Date Montana State Preservation Office State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service -

Protecting the Crown: a Century of Resource Management in Glacier National Park

Protecting the Crown A Century of Resource Management in Glacier National Park Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (RM-CESU) RM-CESU Cooperative Agreement H2380040001 (WASO) RM-CESU Task Agreement J1434080053 Theodore Catton, Principal Investigator University of Montana Department of History Missoula, Montana 59812 Diane Krahe, Researcher University of Montana Department of History Missoula, Montana 59812 Deirdre K. Shaw NPS Key Official and Curator Glacier National Park West Glacier, Montana 59936 June 2011 Table of Contents List of Maps and Photographs v Introduction: Protecting the Crown 1 Chapter 1: A Homeland and a Frontier 5 Chapter 2: A Reservoir of Nature 23 Chapter 3: A Complete Sanctuary 57 Chapter 4: A Vignette of Primitive America 103 Chapter 5: A Sustainable Ecosystem 179 Conclusion: Preserving Different Natures 245 Bibliography 249 Index 261 List of Maps and Photographs MAPS Glacier National Park 22 Threats to Glacier National Park 168 PHOTOGRAPHS Cover - hikers going to Grinnell Glacier, 1930s, HPC 001581 Introduction – Three buses on Going-to-the-Sun Road, 1937, GNPA 11829 1 1.1 Two Cultural Legacies – McDonald family, GNPA 64 5 1.2 Indian Use and Occupancy – unidentified couple by lake, GNPA 24 7 1.3 Scientific Exploration – George B. Grinnell, Web 12 1.4 New Forms of Resource Use – group with stringer of fish, GNPA 551 14 2.1 A Foundation in Law – ranger at check station, GNPA 2874 23 2.2 An Emphasis on Law Enforcement – two park employees on hotel porch, 1915 HPC 001037 25 2.3 Stocking the Park – men with dead mountain lions, GNPA 9199 31 2.4 Balancing Preservation and Use – road-building contractors, 1924, GNPA 304 40 2.5 Forest Protection – Half Moon Fire, 1929, GNPA 11818 45 2.6 Properties on Lake McDonald – cabin in Apgar, Web 54 3.1 A Background of Construction – gas shovel, GTSR, 1937, GNPA 11647 57 3.2 Wildlife Studies in the 1930s – George M. -

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL COPYRIGHTED I

Avalanche Campground (MT), 66 Big Horn Equestrian Center (WY), Index Avenue of the Sculptures (Billings, 368 MT), 236 Bighorn Mountain Loop (WY), 345 Bighorn Mountains Trail System INDEX A (WY), 368–369 AARP, 421 B Bighorn National Forest (WY), 367 Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Backcountry camping, Glacier Big Red (Clearmont, WY), 370 (MT), 225–227 National Park (MT), 68 Big Red Gallery (Clearmont, WY), Academic trips, 44–45 Backcountry permits 370 Accommodations, 413–414 Glacier National Park (MT), Big Salmon Lake (MT), 113 best, 8–10 54–56 Big Sheep Creek Canyon (MT), 160 for families with children, 416 Grand Teton (WY), 325 Big Sky (MT), 8, 215–220 Active vacations, 43–52 Yellowstone National Park Big Sky Brewing Company AdventureBus, 45, 269 (MT—WY), 264 (Missoula, MT), 93 Adventure Sports (WY), 309, 334 Backcountry Reservations, 56 Big Sky Candy (Hamilton, MT), 96 Adventure trips, 45–46 Backcountry skiing, 48 Big Sky Golf Course (MT), 217 AdventureWomen, 201–202 Backroads, 45, 46 Big Sky Resort (MT), 216–217 Aerial Fire Depot and Baggs (WY), 390 Big Sky Waterpark (MT), 131 Smokejumper Center (Missoula, Ballooning, Teton Valley (WY), Big Spring (MT), 188 MT), 86–87 306 Big Spring Creek (MT), 187 Air tours Bannack (MT), 167, 171–172 Big Timber Canyon Trail (MT), 222 Glacier National Park (MT), 59 Bannack Days (MT), 172 Biking and mountain biking, 48 the Tetons (WY), 306 Barry’s Landing (WY), 243 Montana Air travel, 409, 410 Bay Books & Prints (Bigfork, MT), Big Sky, 216 Albright Visitor Center 105 Bozeman, 202 (Yellowstone), 263, 275 -

A Historical Note

A Historical Note We have included the information on this page to show you the original procedure that the Sioux used to determine the proper tripod pole measurements. If you have a tipi and do not know what size it is (or if you lose this set up booklet) you would use the method explained on this page to find your exact tripod pole lengths. It is simple and it works every time. We include this page only as an interesting historical reference. You will not need to follow the instructions on this page. The complete instructions that you will follow to set up your Nomadics tipi begin on page 4. All the measurements you will need are already figured out for you starting on page 5. -4”- In order to establish the proper position and length for the door pole, start at A and walk around the edge of the tipi cover to point B. Walk toe-to-heel one foot in front of the other and count your steps from A to B. Let us say for instance that you count 30 steps from A to B. Simply divide 30 by 1/3. This gives you 10. That means that you start again at A and walk toe-to- heel around the edge of the tipi cover 10 steps, going towards B again. Stop at 10 steps and place the end of the door pole (D) at that point on the edge of the tipi cover. Your three tripod poles should now look like the drawing above. The north and south poles going side by side down the middle of the tipi cover, the door pole placed 1/3 of the way from A to B, and the door pole crossing the north and south poles at Z. -

CENTENNIAL Celebratingsaving GLACIER’S the Hundredthreds, Again

Voice of the Glacier Park Foundation ☐ Winter 2013 ☐ Volume XXVIII, No. 1 CENTENNIAL CELEBRATINGSaving GLACIER’S the HUNDREDTHReds, again... (Photo courtesy of Bret Bouda) The public rallies to prevent retirement of Glacier’s historic bus fleet – probably the oldest in the world Also In this issue: • The Bear Attacks of 1967 • Hiking Gunsight Pass • Tales of the Many Glacier Boat Dock • The Buying and Selling of Glacier Park • The Pending Long-Term Concession Contract • The GPL Reunion • In Memorium • Youth and Maturity in Glacier The Inside Trail ◆ Winter 2005 ◆ 1 Editorial: The Importance of Public Involvement The National Park Service generally groups and public meetings, and resources in the park. In the pres- does well-considered and admirable eventually issued a moderate plan ent case, however, it made a major work in managing Glacier National that enjoyed almost universal sup- decision without public input – and Park. On rare occasions, however, port. almost everyone now recognizes that the decision was wrong. We com- it makes a major misjudgment, and A similar episode just has trans- mend Acting Superintendent Kym the public has to call for a change of pired. (See “Saving the Reds,” p. Hall and her colleagues for promptly course. 3) Prompt public objection and a and graciously changing course. A notable instance occurred in 1996. change of course by the Park Service At that time, the Park Service re- has resolved the situation. But it The lesson of 1996, repeated here, leased a draft General Management shows the importance of active con- is for the Park Service to solicit Plan for Glacier. -

Nordic Tipis – a Home for Big and Small Adventures ROOTS

ADVENTURE Nordic tipis – a home for big and small adventures ROOTS THE PEOPLE OF THE SUN AND WIND The Sami are the only indigenous people in Europe. They used to live as nomadic trackers, hunters and reindeer keepers. Their country Sápmi extends over northern Scandinavia and parts of Russia. The tough climate, the long winter and nature’s tribulations were part of these people’s everyday life. The lifecycle of the reindeer was also theirs and they accompanied their animals to their summer and winter grazing grounds. Traditionally, the Sami lived in a “kåta” in the winter. The focal point of the tent was the fire which gave them heat and light and a feel of homeliness. Our company was started in Moskosel, a little village in Swedish Lapland, where the Sami heritage is ever present. Our hope is that, when you choose a Tentipi Nordic tipi, you will feel the same closeness to the elements as the indigenous people do. Separating the reindeer – an activity steeped in cultural heritage that is still a central part of reindeer husbandry © Peter Rosén CONTENT 04 Adventure tent range 24 Stove and fire equipment 26 Tent accessories 31 Sustainability 32 Handicraft and material 34 Crucial features 36 Event tents 38 Tentipi Camp 39 Further reading Wanted: a home in nature The idea came to me when I was sitting by a stream, far out in the wilds of Lapland. Tired and sweaty after a long day of exciting canoeing, what I really wanted to do was socialise with my friends while eating dinner and chatting around a fire. -

The Insider's Guide

THE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO: GLACIER NATIONAL PARK, MONTANA There’s a reason Glacier National Park is on practically every Top 10 list involving national parks ever created: this place is amazing. But it’s even more amazing when you experience it as the locals do. Ready to plan your trip with a guide from the inside? Let us help. We are Glacier Guides and Montana Raft, and since 1983, we’ve been your Glacier National Park experts. Glacier Guides and Montana Raft | Glacier Guides Lodge | Glacier Guides Guest House www.glacierguides.com | 406-387-5555 | [email protected] TOP TEN ADVENTURES IN AND AROUND GLACIER NATIONAL PARK #1 HIKING OR BACKPACKING We could never choose just one hike. But with 734 miles of hiking trails, you’re sure to find the trail that suits your group’s abilities and desires. Glacier Guides was chosen by the National Park Service as the exclusive backpacking guide service in Glacier National Park. Join us for a half, whole, or multiple day hiking experience. Scheduled trips leave daily. #2 WHITEWATER RAFTING OR FLOATING The most refreshing way to see Glacier National Park? From the rivers that make up its borders, the North and Middle Forks of the Flathead, a Wild and Scenic River. From lazy floats to intense whitewater rapids, there’s something for kids, grandparents, and adrenaline junkies, too. Call Glacier Guides and Montana Raft to set up your perfect paddling adventure! We rent boats, inflatable kayaks, stand up paddleboards, zayaks, and river gear, too. #3 INTERPRETIVE BOAT TOUR Kids and adults alike will be blown away by the views of Glacier National Park from the middle of one of its beautiful lakes.