MISOVERESTIMATING TERRORISM John Mueller Ohio State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time

The Business of Getting “The Get”: Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung The Joan Shorenstein Center I PRESS POLITICS Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 IIPUBLIC POLICY Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government The Business of Getting “The Get” Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 INTRODUCTION In “The Business of Getting ‘The Get’,” TV to recover a sense of lost balance and integrity news veteran Connie Chung has given us a dra- that appears to trouble as many news profes- matic—and powerfully informative—insider’s sionals as it does, and, to judge by polls, the account of a driving, indeed sometimes defining, American news audience. force in modern television news: the celebrity One may agree or disagree with all or part interview. of her conclusion; what is not disputable is that The celebrity may be well established or Chung has provided us in this paper with a an overnight sensation; the distinction barely nuanced and provocatively insightful view into matters in the relentless hunger of a Nielsen- the world of journalism at the end of the 20th driven industry that many charge has too often century, and one of the main pressures which in recent years crossed over the line between drive it as a commercial medium, whether print “news” and “entertainment.” or broadcast. One may lament the world it Chung focuses her study on how, in early reveals; one may appreciate the frankness with 1997, retired Army Sergeant Major Brenda which it is portrayed; one may embrace or reject Hoster came to accuse the Army’s top enlisted the conclusions and recommendations Chung man, Sergeant Major Gene McKinney—and the has given us. -

Religious Education

RELIGIOUS EDUCATION OF MANY THINGS ore than halfway through story that simply sells is clearly evident in 106 West 56th Street New York, NY 10019-3803 the general election, Donald much of what they do. Ph: (212) 581-4640; Fax: (212) 399-3596 Trump’s presidential campaign Scott Pelley, the veteran anchor of the Subscriptions: (800) 627-9533 M www.americamedia.org is imploding. The Republican flagship “CBS Evening News,” may not be the facebook.com/americamag resembles Jonah’s boat to Tarshish: most exciting personality on television, twitter.com/americamag but he is undoubtedly the best journalist, the tempest-tossed and panic-stricken PRESIDENT AND EDITOR IN CHIEF passengers are looking for someone to a worthy heir to the legacy of Paley, Matt Malone, S.J. blame, someone they can sacrifice to Murrow and Cronkite, something EXECUTIVE EDITORS their angry god. that Mr. Pelley takes seriously. He has Robert C. Collins, S.J., Maurice Timothy Reidy MANAGING EDITOR Kerry Weber Mr. Trump’s favorite scapegoat avoided blurring the line between news LITERARY EDITOR Raymond A. Schroth, S.J. these days is the national media. "If the and entertainment, saying that “there’s SENIOR EDITOR AND CHIEF CORRESPONDENT disgusting and corrupt media covered too much of a risk for the audience to Kevin Clarke me honestly and didn't put false meaning think ‘Wait a minute—is it scripted? Is EDITOR AT LARGE James Martin, S.J. CREATIVE DIRECTOR Shawn Tripoli into the words I say, I would be beating it not? Are you telling me the truth? Is it EXECUTIVE EDITOR, AMERICA FIlmS Hillary by 20 percent," he recently acting?’ That’s a big red line for me, and I Jeremy Zipple, S.J. -

Newspro Cuts a Wide Swath

December 2014 Entries Go to Great Lengths Longform Awards Submissions Reach New Heights Page 10 Footing the Innovation Bill Grant Programs Out to Blaze New Trails Page 12 A Children’s Cause Is Lost The Journalism Center on Children & Families Closes Its Doors Page 14 Our Top 10 J-Schools to Watch Mizzou Takes the No. 1 Spot Once Again 12 in TV News Page 16 Page 4 Plain Speaking on Integrity Author and Educator Charles Lewis Calls for Gravitas in Local Reporting Page 23 14np0054.pdf RunDate:12/15/14 Full Page Color: 4/C FROM THE EDITOR Loss or Gain, It’s Change e subject matter of this issue of NewsPro cuts a wide swath. We feature stories about disruptive change, about loss and gain, and about tradition and innovation. In essence, the terms that best describe the chaotic world of journalism. CONTENTS Our annual “12 to Watch in TV News” feature o ers a look at the professionals who are 12 TO WATCH IN TV NEWS ................. 4 in positions to make their imprint on — and in some cases change — the TV news business. This Year’s Wrap-up of the Pivotal Players You’ll nd among this year’s choices both the expected and a few fresh surprises. in the News Business On the journalism awards front, our piece discovers that the recession-related drop-o in submissions appears to be over for good, with programs reporting a notable gain in entries, AWARDS PROGRAMS ADAPT ........... 10 particularly of the longform variety — a development that has caused a dire need for change in Longform and Multimedia Entries Change the the way those organizations judge accomplishment. -

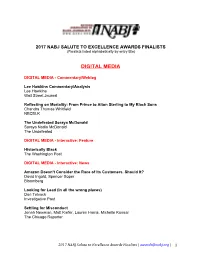

Digital Media

2017 NABJ SALUTE TO EXCELLENCE AWARDS FINALISTS (Finalists listed alphabetically by entry title) DIGITAL MEDIA DIGITAL MEDIA - Commentary/Weblog Lee Hawkins Commentary/Analysis Lee Hawkins Wall Street Journal Reflecting on Mortality: From Prince to Alton Sterling to My Black Sons Chandra Thomas Whitfield NBCBLK The Undefeated Soraya McDonald Soraya Nadia McDonald The Undefeated DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: Feature Historically Black The Washington Post DIGITAL MEDIA - Interactive: News Amazon Doesn’t Consider the Race of Its Customers. Should It? David Ingold, Spencer Soper Bloomberg Looking for Lead (in all the wrong places) Dan Telvock Investigative Post Settling for Misconduct Jonah Newman, Matt Kiefer, Lauren Harris, Michelle Kanaar The Chicago Reporter 2017 NABJ Salute to Excellence Awards Finalists | [email protected] | 1 DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: Feature The City: Prison's Grip on the Black Family Trymaine Lee NBC News Digital Under Our Skin Staff of The Seattle Times The Seattle Times Unsung Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement Eric Barrow New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Online Project: News Chicago's disappearing front porch Rosa Flores, Mallory Simon, Madeleine Stix CNN Machine Bias Julia Angwin, Jeff Larson, Surya Mattu, Lauren Kirchner, Terry Parris Jr. ProPublica Nuisance Abatement Sarah Ryley, Barry Paddock, Pia Dangelmayer, Christine Lee ProPublica and The New York Daily News DIGITAL MEDIA > Single Story: Feature Congo's Secret Web of Power Michael Kavanagh, Thomas Wilson, Franz Wild Bloomberg Migration and Separation: -

This Interview Is Part of the Southern Oral History Program Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

1 This interview is part of the Southern Oral History Program collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Other interviews from this collection are available online through www.sohp.org and in the Southern Historical Collection at Wilson Library. R.43. Special Research Projects: NewStories Interview R-0774 Richard Griffiths 17 March 2015 Abstract – p. 2 Transcript – p. 3 Interview number R-0774 from the Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007) at The Southern Historical Collection, The Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill. 2 GRIFFITHS, RICHARD T. - ABSTRACT For Richard T. Griffiths, vice president and senior editorial director of CNN, success is built on high standards, long hours and forward thinking. Being in the right place at the right time helps, too. Griffiths and his family emigrated from England in 1974 for his father’s job developing telecommunications technology. This provided Griffiths with the opportunity to attend and graduate from an American high school, an experience that set him on an “extraordinary path,” he said. He went on to college at UNC-Greensboro as a sociology major. While he was a student, he worked various journalism jobs to pay his expenses through college. Yet success as a journalist left less and less time for classes, and ultimately Griffiths chose work over completing his degree. The choice hasn’t held him back. Griffiths’s path to CNN was circuitous. He worked in Greensboro as a news director at WGBG Radio; as a motel desk clerk at Howard Johnson’s; and in numerous positions at WFMY television, the CBS affiliate. -

SPRING 2013 Volume 7, Issue 1 SVG UPDATE 9 Sportspost:NY 36 12 League Technology Summit 26 Transport 36 Sports Venue Technology Summit

ADVANCING THE CREATION, PRODUCTION, & DISTRIBUTION OF SPORTS CONTENT Spring 2013 • Volume 7, iSSUE 1 AN PUBLICATION SVG SPECIAL REPORT: THE BIG SHOW FROM THE BIG EASY Inside the Super Bowl XLVII Compound in New Orleans • SVG Update: In-Depth Recaps of Recent SVG Events • Sports Broadcasting Hall of Fame: The Class of 2012 • White Papers: The Promise of 4K, Streaming the Pac-12 Networks, and Workflow Automation in Sports plus Comprehensive 2013 NAB Preview & SVG Sponsor Update UPFRONT IN THIS ISSUE 4 FROM THE CHAIRMAN Even With 4K, the Future of Sports Video Is Better HD 6 THE TIp-off Standing Up For Your Rights SPRING 2013 VOLUME 7, ISSUE 1 SVG UPDATE 9 SportsPost:NY 36 12 League Technology Summit 26 TranSPORT 36 Sports Venue Technology Summit 42 SVG SPECIAL REPORT: THE BIG GAME FROM THE BIG EASY SPORTS BROADCASTING HALL OF FAME Class of 2012 Coverage begins on page 54 56 George Bodenheimer 64 Cory Leible 58 Ray Dolby 66 Paul Tagliabue 60 Frank Gifford 68 Jack Weir 62 Ed Goren 70 Jack Whitaker 72 WHITE PAPERS 80 72 Canon: The Promise of 4K 76 iStreamPlanet: Live Linear Streaming 80 Wohler: File-based Workflow Automation 3 2 1 8 4 PRODUCT NEWS 15 32 84 Remote Sports Production Gearbase 18 More trucks, more gear, more consolidation 111 87 NAB Preview 84 A comprehensive look at what SVG Sponsors will showcase in Las Vegas 122 Sponsor Update New technology, news, and innovations 87 138 SVG SPONSOR INDEX 144 THE FINAL BUZZER A Measured Response to 4K Hype? The SportsTech Journal is produced and published by the Sports Video Group. -

12 to Watch in Tv News

January 2018 CrainsNewsPro.com Streaming for Local TV News Newsrooms May Soon Have More Online Options Page 16 The Top of the Learning Curve Our New Survey Identifies 10 Stand-out Educators Page 17 12 to Watch Why Journalism IN TV NEWS Is Generalism Page 4 Great Journalists Are Educated Generalists First Page 21 Fostering Change With Fellowships Programs Expand Career Opportunities Page 22 Countering the Attack on Media Journalists Are Fighting Back By Getting Better Page 27 P001_NP_20180101.pdf RunDate: 01/08/18 Full Page Color: 4/C P002_NP_20180101.pdf RunDate: 01/08/18 Full Page Color: 4/C )5207+((',725 CrainsNewsPro.com Excellence in Tubulent Times As 2018 begins, we’re coming o a troubling year for journalism. From “fake news” to physical attacks on journalists, the downfall of several respected newsmen amid allegations of sexual misconduct and the ongoing cutbacks and layo s hitting newrooms, &217(176 our profession has been confronting a serious onslaught on many sides — even from 12 TO WATCH IN TV NEWS ................. 4 within, as news professionals become more cynical and stressed. A Look at the Notable Players in the News And yet, as demonstrated in this issue of NewsPro, many people maintain their faith Business for 2018 in the power of journalism to a ect change and make a di erence in the lives of people around the world. THE FUTURE OF NEWS .................... 14 Our annual “12 to Watch in TV News” showcases key people who are working to BEA’s Michael Bruce on How to Prepare the make a di erence, from NBC News’ Peter Alexander, who stood up to public ridicule Next Generation of Journalists from President Donald Trump, to “CBS is Morning’s” Gayle King and Norah LOCAL STREAMING ......................... -

Truth on Trial: Implications for Communicators (On-Demand Video)

Truth on Trial: Implications for Communicators (On-Demand Video) #TruthOnTrial Event Overview Major Garrett, Chief White House Correspondent, CBS News; Richard S. Levick, Chairman & CEO, LEVICK; Joe Lockhart, Former Press Secretary to President Clinton; Michael Zeldin, CNN Legal Analyst; Anthony Scaramucci, Former White House Communications Director for President Trump; Sheryl Battles, VP, Communications and Diversity Strategy at Pitney Bowes and others … A week before the mid-term elections, hear them talk about how today’s communicators need to navigate a world where fake news, Russian intelligence operatives and biased-information can affect the truth and the trust of the institutions in the United States. Our speakers will discuss topics including: What steps can business take to help restore trust in our institutions and our democracy? How do companies and communicators work in an environment where there are no sidelines and every utterance is subject to criticism through a political lens? How do we anticipate and minimize issues that will divide customers and shareholders? How do we handle them once they have become politicized? What will the likely impact of the midterms be for communicators in this red hot environment? What do we need to do differently? What are the unique challenges and best practices for publicly traded companies? Speakers Just added… Anthony Scaramucci, Former White House Communications Director for President Trump Anthony Scaramucci is the Founder and Co-Managing Partner of SkyBridge Capital. He is the author of three books: The Little Book of Hedge Funds, Goodbye Gordon Gekko, and Hopping Over the Rabbit Hole, a 2016 Wall Street Journal best- seller. -

Norwalk Community College Foundation Will Host 60 Minutes Reporter Scott Pelley to Present Truth Worth Telling

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Trevor Stonefield [email protected] 203.857.7260 NORWALK COMMUNITY COLLEGE FOUNDATION WILL HOST 60 MINUTES REPORTER SCOTT PELLEY TO PRESENT TRUTH WORTH TELLING On Thursday, October 17, from 7:30am to 9:30am at the Norwalk Community College David L. Levinson Theater, Scott Pelley will present his engaging new memoir Truth Worth Telling: A Reporter’s Search for Meaning in the Stories of Our Time. Tickets are available now which include breakfast and a signed copy of Pelley’s book. To purchase: scottpelleyatncc.eventbrite.com. NORWALK, CT, September 16 2019— In an engaging presentation of his new memoir, Truth Worth Telling, Scott Pelley will revisit some of the stories and people that have stirred him, changed him, and stayed with him over his nearly five decades as a journalist. From interviewing everyone from presidents and politicians, to celebrities and newsmakers, Pelley has gained insights and anecdotes that are sure to be both entertaining and thought-provoking in this unique book event at Norwalk Community College. Scott Pelley has been a reporter and photographer for more than 45 years. He is best known for his work on 60 Minutes and as an anchor and managing editor of the CBS Evening News. Pelley’s work has been recognized with three duPont-Columbia Awards, three Peabody Awards, the Walter Cronkite Award for Excellence in Journalism, and 37 Emmy Awards. Pelley is the most awarded correspondent in the history of 60 Minutes. All proceeds from the event will benefit the Norwalk Community College Foundation. About the Norwalk Community College Foundation The Norwalk Community College Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that supports expanding access to affordable, quality higher education, the development of a productive workforce, and contributing to the knowledge and well-being of our community by raising funds for Norwalk Community College. -

31St Annual News & Documentary Emmy Awards

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES 31st Annual News & Documentary EMMY AWARDS CONGRATULATES THIS YEAR’S NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® NOMINEES AND HONOREES WEEKDAYS 7/6 c CONGRATULATES OUR NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® NOMINEES Outstanding Continuing Coverage of a News Story in a Regularly Scheduled Newscast “Inside Mexico’s Drug Wars” reported by Matthew Price “Pakistan’s War” reported by Orla Guerin WEEKDAYS 7/6 c 31st ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY ® AWARDS LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT / FREDERICK WISEMAN CHAIRMAN’S AWARD / PBS NEWSHOUR EMMY®AWARDS PRESENTED IN 39 CATEGORIES NOMINEES NBC News salutes our colleagues for the outstanding work that earned 22 Emmy Nominations st NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION CUSTOM 5 ARTS & SCIENCES / ANNUAL NEWS & SUPPLEMENT 31 DOCUMENTARY / EMMY AWARDS / NEWSPRO 31st Annual News & Documentary Letter From the Chairman Emmy®Awards Tonight is very special for all of us, but especially so for our honorees. NATAS Presented September 27, 2010 New York City is proud to honor “PBS NewsHour” as the recipient of the 2010 Chairman’s Award for Excellence in Broadcast Journalism. Thirty-five years ago, Robert MacNeil launched a nightly half -hour broadcast devoted to national and CONTENTS international news on WNET in New York. Shortly thereafter, Jim Lehrer S5 Letter from the Chairman joined the show and it quickly became a national PBS offering. Tonight we salute its illustrious history. Accepting the Chairman’s Award are four S6 LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT dedicated and remarkable journalists: Robert MacNeil and Jim Lehrer; HONOREE - FREDERICK WISEMAN longtime executive producer Les Crystal, who oversaw the transition of the show to an hourlong newscast; and the current executive producer, Linda Winslow, a veteran of the S7 Un Certain Regard By Marie-Christine de Navacelle “NewsHour” from its earliest days. -

Special Report: Journalists Face Arrests, Attacks, and Threats by Police Amidst Protests Over the Death of George Floyd N May 2020, Protests in Minneapolis, Minn

A PUBLICATION OF THE SILHA CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF MEDIA ETHICS AND LAW | WINTER/SPRING 2020 A Message from the Director This issue of the Silha Bulletin, produced by our graduate student research assistants, includes a special roundup examining how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected newsgathering and reporting. But as if our world has not been rocked enough by COVID-19, the civil unrest in the Twin Cities following the death of George Floyd on May 25 prompted us to pivot just as we were wrapping up this issue of the Bulletin. Please visit our website to see our running list of clashes between the press and law enforcement. Our website is available at: https://hsjmc.umn.edu/news/2020-06-02-list-incidents-involving-police-and-journalists-during-civil-unrest-minneapolis-mn. We haven’t neglected our usual analysis of significant media law and media ethics developments from around the country. We’ve continued to provide timely research assistance and commentary on issues affecting freedom of the press and the public’s right to know. Elaine Hargrove, Silha Program Assistant, has almost completed a massive migration of Silha Center content — including past issues of the Bulletin, research materials, and photographs and recordings of many Silha events — to our new web site: https://hsjmc. umn.edu/research-centers/centers/silha-center-study-media-ethics-and-law. Silha Center programming and outreach also continue. On June 3, we participated in the first of a series of Town Hall webinars hosted by the Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication examining legal and ethical issues surrounding reporting on the civil unrest in the Twin Cities. -

NOMINEES for the 40Th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY

NOMINEES FOR THE 40th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED NBC’s Andrea Mitchell to be honored with Lifetime Achievement Award September 24th Award Presentation at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in NYC New York, N.Y. – July 25, 2019 (revised 8.19.19) – Nominations for the 40th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy Awards will be presented on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019, at a ceremony at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. “The clear, transparent, and factual reporting provided by these journalists and documentarians is paramount to keeping our nation and its citizens informed,” said Adam Sharp, President & CEO, NATAS. “Even while under attack, truth and the hard-fought pursuit of it must remain cherished, honored, and defended. These talented nominees represent true excellence in this mission and in our industry." In addition to celebrating this year’s nominees in forty-nine categories, the National Academy is proud to honor Andrea Mitchell, NBC News’ chief foreign affairs correspondent and host of MSNBC's “Andrea Mitchell Reports," with the Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award for her groundbreaking 50-year career covering domestic and international affairs. The 40th Annual News & Documentary Emmy® Awards honors programming distributed during the calendar