Ealy-Projectreport.Pdf (1.259Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

Course Outline and Syllabus the Fab Four and the Stones: How America Surrendered to the Advance Guard of the British Invasion

Course Outline and Syllabus The Fab Four and the Stones: How America surrendered to the advance guard of the British Invasion. This six-week course takes a closer look at the music that inspired these bands, their roots-based influences, and their output of inspired work that was created in the 1960’s. Topics include: The early days, 1960-62: London, Liverpool and Hamburg: Importing rhythm and blues and rockabilly from the States…real rock and roll bands—what a concept! Watch out, world! The heady days of 1963: Don’t look now, but these guys just might be more than great cover bands…and they are becoming very popular…Beatlemania takes off. We can write songs; 1964: the rock and roll band as a creative force. John and Paul, their yin and yang-like personal and musical differences fueling their creative tension, discover that two heads are better than one. The Stones, meanwhile, keep cranking out covers, and plot their conquest of America, one riff at a time. The middle periods, 1965-66: For the boys from Liverpool, waves of brilliant albums that will last forever—every cut a memorable, sing-along winner. While for the Londoners, an artistic breakthrough with their first all--original record. Mick and Keith’s tempestuous relationship pushes away band founder Brian Jones; the Stones are established as a force in the music world. Prisoners of their own success, 1967-68: How their popularity drove them to great heights—and lowered them to awful depths. It’s a long way from three chords and a cloud of dust. -

UCLA's National Team Champions

UCLA’s National Team Champions After being voted the pre-season tie with Michigan with 1997 No. 1, UCLA watched as Georgia one rotation remaining assumed the role of favorites dur- - UCLA on bars and ing the regular season. But when Michigan on fl oor. it counted the most, the Bruins proved they were worthy of their early ranking by With Michigan falter- winning the NCAA Championship. ing on fl oor, the Bruins needed a 49.25 to sur- Before UCLA even began its competition at the Super pass ASU for the cham- Six Team Finals, the door had opened. As the Bruins pionship. Deborah Mink were taking a fi rst-rotation bye, Georgia was stumbling started with a 9.825. on beam, counting two falls to essentially take the Gym Kiralee Hayashi fol- Dogs out of the running. The pressure then shifted to lowed with a 9.85. Lena the Bruins, who would follow on the dreaded beam. Degteva nailed a 9.875, and Umeh followed with But the Bruins were undaunted by the pressure. a 9.925. Freshman Heidi Leadoff competitor Susie Erickson hit a career-high Moneymaker needed 9.85 to start the ball rolling. A fall in the third position just a 9.775 to clinch put a scare into the Bruins, but they rallied to hit their the championship and routines - Leah Homma for a 9.8, Luisa Portocarrero scored that and more for a 9.825, and Stella Umeh with a spectacular 9.925 with a 9.925. Homma’s The 1997 Bruins (clockwise, l-r) - Susie Erickson, Carmen Tausend, Lena Degteva, Heidi - to take themselves safely past the most nerve-racking 9.95 to close the com- event in the competition with a score of 49.2. -

Behindthe Story

The Story Behind the Story Dr. Jonathan LaPook reflects on his 60 Minutes Alzheimer’s Feature SUMMER 2018 MISSION: “TO PROVIDE OPTIMAL CARE AND SERVICES TO INDIVIDUALS LIVING WITH DEMENTIA — AND TO THEIR CAREGIVERS AND FAMILIES — THROUGH MEMBER ORGANIZATIONS DEDICATED TO IMPROVING QUALITY OF LIFE” FEATURES PAGE 2 PAGE 8 PAGE 12 Teammates The Story Behind the 60 Seizures in Individuals Minutes Story with Alzheimer’s PAGE 14 PAGE 16 PAGE 18 Respect Selfless Love The Special Bonds Chairman of the Board The content of this magazine is not intended to Bert E. Brodsky be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of Board of Trustees Publisher a physician or other qualified health provider with Gerald (Jerry) Angowitz, Esq. Alzheimer’s Foundation of America any questions you may have regarding a medical Barry Berg, CPA condition. Never disregard professional medical Luisa Echevarria Editor advice or delay in seeking it because of something Steve Israel Chris Schneider you have read in this magazine. The Alzheimer’s Edward D. Miller Foundation of America makes no representations as Design to the accuracy, completeness, suitability or validity Associate Board Members The Monk Design Group of any of the content included in this magazine, Matthew Didora, Esq. which is provided on an “as is” basis. The Alzheimer’s Arthur Laitman, Esq. Foundation of America does not recommend or CONTACT INFORMATION Judi Marcus endorse any specific tests, physicians, products, Alzheimer’s Foundation of America procedures, opinions or other information that may 322 Eighth Ave., 7th floor President & Chief Executive Officer be mentioned in this magazine. -

Opinion | Sylvia Chase and the Boys' Club of TV News

SUNDAY REVIEW Sylvia Chase and the Boys’ Club of TV News When we started at the networks in the early ’70s, most of us tried to hide our gender. Sylvia spoke out. By Lesley Stahl Ms. Stahl is a correspondent for “60 Minutes.” Jan. 12, 2019 Back in the early 1970s, the TV network news organizations wanted to show the world that they were “equal opportunity employers.” And so, CBS, ABC and NBC scoured the country for women and minorities. In 1971, Sylvia Chase was a reporter and radio producer in Los Angeles, and I was a local TV reporter in Boston. CBS hired her for the New York bureau; I was sent to Washington. Sylvia, who died last week at age 80, and I were CBS’s affirmative action babies, along with Connie Chung and Michele Clark. To ensure we had no illusions about our lower status, we were given the title of “reporter.” We would have to earn the position of “correspondent” that our male colleagues enjoyed. We were more like apprentices, often sent out on stories with the seniors, like Roger Mudd and Daniel Schorr. While we did reports for radio, the “grown-ups” — all men — did TV, but we were allowed to watch how they developed sources, paced their days and wrote and edited their stories. Up until then, most women in broadcast journalism were researchers. At first, the four of us in our little group were grateful just to be in the door as reporters. Things began to stir when the women at Newsweek sued over gender discrimination. -

HEALTH CARE JOURNALISM As This Year’S Major Issue

TW MAIN 04-13-09 A 13 TVWEEK 4/9/2009 6:26 PM Page 1 REWARDING EXCELLENCE TELEVISIONWEEK April 13, 2009 13 AHCJ AWARD WINNERS INCLUDE ‘NEWSHOUR,’ RLTV, AL JAZEERA. FULL LIST, PAGE 20 SPECIAL SECTION INSIDE Feeling the Pain NewsproTHE STATE OF TV NEWS The economy’s troubles finally are taking their toll on health care journalists. Page 14 Q&A: On the Horizon AHCJ Executive Director Len Bruzzese sees health care reform HEALTH CARE JOURNALISM as this year’s major issue. Page 14 Helping Underserved A Health Journalism panel will address how to ID and improve UNDER areas that need doctors. Page 24 Comprehending Reform The Obama administration THE promises health care reform, and journalists must explain what that means to the public. Page 26 Q&A: Broad Perspective CBS’ Dr. Jon LaPook draws on his medical Despite Increased Interest in Medical Issues, practice to KNIFE supplement his Media Outlets Are Cutting Health Care Coverage broadcast expertise. Page 26 By Debra Kaufman Special to TelevisionWeek Miracle Babies? The bad economy has been a double whammy for journalists: Not only have the What started as a heart-warming funds in their 401(k)s disappeared, but so have the media outlets they work for. story became one of the biggest At first, health care journalists seemed impervious to the axes falling in media “gets” of the year. Page 27 organizations. “With regard to layoffs, health care journalism lagged behind some Online Draw other areas in journalism because the topic is of great interest to Where do laid- PhRMA’s Web series “Sharing off health care viewers,” said Trudy Lieberman, president of the Association of Miracles” is gaining a global journalists go? Health Care Journalists and director of the health and medicine audience. -

St. Francis College Terrier Magazine | Fall 2019, Volume 83, Number 1

First Master of Fine Arts Degrees Awarded 2019 SFC Literary Prize Arts at SFC The McGuire Scholars: First Class Graduates President Miguel Martinez-Saenz, Ph.D., and McGuire Scholar Antonia Meditz ’19, the 2019 Spring Commencement THE ST. FRANCIS COLLEGE MAGAZINE | FALL 2019, VOLUME 83, NUMBER 1 TERRIER BOARD OF TRUSTEES ALUMNI BOARD OF DIRECTORS Fall 2019 Volume 83, Number 1 CHAIRMAN PRESIDENT Terrier, the magazine of St. Francis College, Denis Salamone ’75 Robert L. Smith ’72 is published by the Office of Marketing and Communications for alumni and friends of TRUSTEES VICE PRESIDENT St. Francis College. Hector Batista ’84, P’17 Patricia Moffatt Lesser ’77 Bro. William Boslet, OSF ’70 Linda Werbel Dashefsky SECRETARY Rev. Msgr. John J. Bracken Vice President for Kevin T. Conlon ’11 Government and Community Relations Kate Cooney Burke Thomas F. Flood Timothy Cecere P’20 DIRECTORS Vice President for Advancement William Cline Joseph M. Acciarito ’12 Bro. Leonard Conway, OSF ’71 James Bozart ’86 Tearanny Street John J. Casey ’70 Executive Director, Edward N. Constantino ’68 Marketing and Communications Kenneth D. Daly ’88 Salvatore Demma ’09 and ’11 Mary Beth Dawson, Ph.D. Joseph Hemway ’84 EDITOR William F. Dawson, Jr. ’86 Dorothy Henigman-Gurreri ’79 Leah Schmerl Jean S. Desravines ’94 Sarah Bratton Hughes ’07 Director of Integrated Communications, Gene Donnelly ’79 Mary Anne Killeen ’78 Marketing and Communications Catherine Greene Josephine B. Leone ’08 CONTRIBUTORS Leslie S. Jacobson, Ph.D. Alfonso Lopez ’06 Rob DeVita ’15 Penelope Kokkinides James H. McDonald ’69 Kathleen A. Mills ’09 Joey Jarzynka Barbara G. Koster ’76 Jesus F. -

A's News Clips, Saturday, July 23, 2011 New York Yankees Put Hurt

A’s News Clips, Saturday, July 23, 2011 New York Yankees put hurt on Trevor Cahill, Oakland A's in 17-7 romp By Joe Stiglich, Oakland Tribune NEW YORK -- Trevor Cahill took his struggles against the New York Yankees to another level Friday night at Yankee Stadium. The A's right-hander was charged with a career-high 10 earned runs in a 17-7 blowout defeat to open a three-game series. The A's have now lost 11 straight to the Yankees. Cahill allowed nine hits and lasted just two-plus innings in the shortest start of his career. After being staked to a 2-0 lead, he allowed five runs in the bottom of the second. Then he allowed Nick Swisher's three-run homer in the third, as the Yankees batted around in a nine-run rally. Michael Wuertz relieved Cahill in the third but fared no better, walking in two runs before allowing Mark Teixeira's grand slam. Cahill's 10 earned runs were the most allowed by an A's starter since Gio Gonzalez surrendered 11 to the Twins on July 20, 2009. Oakland A's update: Rookie second baseman Jemile Weeks savors first trip to Yankee Stadium By Joe Stiglich, Oakland Tribune NEW YORK -- When A's rookie second baseman Jemile Weeks arrived at Yankee Stadium on Friday afternoon, he immediately went out to the field to take it all in. "You're talking a big deal, first time at Yankee Stadium," Weeks said. "It's an exciting time for me, just to look at the stadium and out into the stands to get a feel of what it's like." Weeks certainly played inspired in his first visit to the ballpark. -

Annualreport 1617 FULL.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – INTRODUCTION Dear Bruins, Our department enjoyed an exciting and memorable year both on and off the field of competition in 2016- 17. Ten of our athletic teams finished among the Top 10, nationally. Of even greater significance, 126 of our student-athletes earned their degrees from this university in June and officially embarked upon the next chapter of their lives. Throughout the 2016-17 academic year, student- athletes earned Director’s Honor Roll accolades (3.0 GPA or higher) more than 980 times. In addition, our Graduation Success Rate (GSR) and Academic Progress Report (APR) numbers remained high across the board and among the best in the nation. UCLA’s overall GSR of 86% stands two percentage points higher than the national average of 84%. Our football team compiled the second-highest GSR among Pac-12 schools with 88% (the national average for FBS schools is 74%). In addition, six of our teams – men’s water polo, women’s basketball, women’s golf, softball, women’s tennis and women’s volleyball – had a GSR of 100 percent. Sixteen of our 20 sports programs had a GSR of 80 percent or higher. I’ve said it before and I’ll say As a department, we always pride ourselves on team practice facilities for our football, men’s basketball it again – our student-athletes not only meet these accomplishments, but it’s absolutely worth noting and women’s basketball teams, and I know that the expectations, but they almost always exceed them. It’s several outstanding individual efforts by our hard- coaches and student-athletes of these teams are a testament to their work ethic and to the support they working student-athletes. -

Programma: Muziek Voor Volwassenen / Johan Derksen

Programma: Muziek voor volwassenen / Johan Derksen Uitzending: 18.00-19.00 uur DATUM: maandag 19/06/17 TIJD TITEL ARTIEST ALBUM TITEL COMPONIST LABEL LABELNR 1 02:55 I saw her standing there Beatles Meet the Beatles Lennon/McCartney Capitol Records .07243 875400 2 6 2 01:49 Come on Rolling Stones Singles Collection - The London Years Berry ABKCO 844 481-2 3 02:15 This boy Beatles Meet the Beatles Lennon/McCartney Capitol Records .07243 875400 2 6 4 01:48 Not fade away Rolling Stones Singles Collection - The London Years Petty/Hardin ABKCO 844 481-2 5 02:13 It won't be long Beatles Meet the Beatles Lennon/McCartney Capitol Records .07243 875400 2 6 6 03:26 It's all over now Rolling Stones Singles Collection - The London Years Bobby & Shirley Womack ABKCO 844 481-2 7 02:03 All I've got to do Beatles Meet the Beatles Lennon/McCartney Capitol Records .07243 875400 2 6 8 02:32 Good times bad times Rolling Stones Singles Collection - The London Years Jagger/Richards ABKCO 844 481-2 9 02:06 Thank you girl Beatles Second album Lennon/McCartney Capitol Records .07243 875400 2 6### 10 02:45 Tell me Rolling Stones Singles Collection - The London Years Jagger/Richards ABKCO 844 481-2 11 02:53 Money Beatles Second album Bradford/Gordy Jr. Capitol Records .07243 875400 2 6 12 02:16 I just want to make love to you Rolling Stones Singles Collection - The London Years Dixon ABKCO 844 481-2 13 02:38 Please Mr. -

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

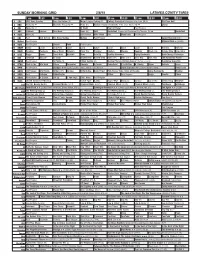

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time

The Business of Getting “The Get”: Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung The Joan Shorenstein Center I PRESS POLITICS Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 IIPUBLIC POLICY Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government The Business of Getting “The Get” Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 INTRODUCTION In “The Business of Getting ‘The Get’,” TV to recover a sense of lost balance and integrity news veteran Connie Chung has given us a dra- that appears to trouble as many news profes- matic—and powerfully informative—insider’s sionals as it does, and, to judge by polls, the account of a driving, indeed sometimes defining, American news audience. force in modern television news: the celebrity One may agree or disagree with all or part interview. of her conclusion; what is not disputable is that The celebrity may be well established or Chung has provided us in this paper with a an overnight sensation; the distinction barely nuanced and provocatively insightful view into matters in the relentless hunger of a Nielsen- the world of journalism at the end of the 20th driven industry that many charge has too often century, and one of the main pressures which in recent years crossed over the line between drive it as a commercial medium, whether print “news” and “entertainment.” or broadcast. One may lament the world it Chung focuses her study on how, in early reveals; one may appreciate the frankness with 1997, retired Army Sergeant Major Brenda which it is portrayed; one may embrace or reject Hoster came to accuse the Army’s top enlisted the conclusions and recommendations Chung man, Sergeant Major Gene McKinney—and the has given us.