The Tucson Mountain Section Administration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unsuitability of the House Finch As a Host of the Brown-Headed Cowbird’

The Condor 98:253-258 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1996 UNSUITABILITY OF THE HOUSE FINCH AS A HOST OF THE BROWN-HEADED COWBIRD’ DANIEL R. KOZLOVIC Department of Zoology, Universityof Toronto, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3G5, Canada RICHARD W. KNAPTON Long Point Waterfowl and WetlandsResearch Fund, P.O. Box 160, Port Rowan, Ontario NOE IMO, Canada JON C. BARLOW Department of Ornithology,Royal Ontario Museum, 100 Queens’ Park, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2C6, Canada and Department of Zoology, Universityof Toronto, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3G5, Canada Abstract. Brown-headedCowbirds (Molothrus ater) parasitized99 (24.4%)of 406 House Finch (Carpodacusmexicanus) nests observed at Barrie,Guelph, Orillia, and St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada,during the periods1983-1985 and 1990-1993.Hatching success of cow- bird eggswas 84.8%, but no cowbirdwas reared.Cowbird growth was severelyretarded; nestlingsrequired about twice as much time to accomplishthe sameamount of growth observedin nestsof otherhosts. Estimated final bodymass of nestlingcowbirds was about 22% lower than normal. Cowbirdnestlings survived on averageonly 3.2 days.Only one cowbirdfledged but died within one day. Lack of cowbirdsurvival in nestsof the House Finch appearsto be the resultof an inappropriatediet. We concludethat nestlingdiet may be importantin determiningcowbird choice of host. Key words: Brown-headed Cowbird; Molothrusater; House Finch; Carpodacusmexi- canus;brood parasitism; cowbirdsurvivorship; nestling diet. INTRODUCTION (Woods 1968). Like other members of the Car- The Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) is duelinae, House Finches are unusual among an obligate brood parasite that lays its eggsin cowbird hosts in that they feed their young pri- the nests of many host species, which provide marily plant material. -

Mt. Tabor Park Breeding Bird Survey Results 2009

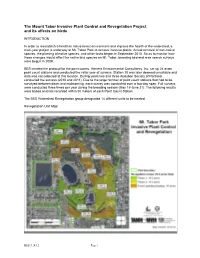

The Mount Tabor Invasive Plant Control and Revegetation Project and its affects on birds INTRODUCTION In order to reestablish a healthier native forest environment and improve the health of the watershed, a multi-year project is underway at Mt. Tabor Park to remove invasive plants. Actual removal of non-native species, the planting of native species, and other tasks began in September 2010. So as to monitor how these changes would affect the native bird species on Mt. Tabor, breeding bird and area search surveys were begun in 2009. BES created the protocol for the point counts. Herrera Environmental Consultants, Inc. set up 24 avian point count stations and conducted the initial year of surveys. Station 10 was later deemed unsuitable and data was not collected at this location. During years two and three Audubon Society of Portland conducted the surveys (2010 and 2011). Due to the large number of point count stations that had to be surveyed between dawn and midmorning, each survey was conducted over a two-day span. Full surveys were conducted three times per year during the breeding season (May 15-June 31). The following results were based on birds recorded within 50 meters of each Point Count Station. The BES Watershed Revegetation group designated 14 different units to be treated. Revegetation Unit Map: BES 3.14.12 Page 1 Point Count Station Location Map: The above map was created by Herrera and shows where the point count stations are located. Point Count Stations are fairly evenly dispersed around Mt. Tabor in a variety of habitats. -

Nest-Site Selection by Western Screech-Owls in the Sonoran Desert, Arizona

Western North American Naturalist Volume 63 Number 4 Article 16 12-3-2003 Nest-site selection by Western Screech-Owls in the Sonoran Desert, Arizona Paul C. Hardy University of Arizona, Tucson Michael L. Morrison University of California, Bishop Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation Hardy, Paul C. and Morrison, Michael L. (2003) "Nest-site selection by Western Screech-Owls in the Sonoran Desert, Arizona," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 63 : No. 4 , Article 16. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol63/iss4/16 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 63(4), ©2003, pp. 533-537 NEST~SITE SELECTION BY WESTERN SCREECH~OWLS IN THE SONORAN DESERT, ARIZONA Paul C. Hardyl,2 and Michael L. Morrison3 Key words: Gila Woodpecker, Gilded Flicker, nest-site selection, Otus kennicottii, saguaro cacti, Sonoran Desert, West ern Screech~Owl. The Western ScreecbOwl (Otus kennicottii) valley includes the creosote (Larrea triden is a small, nocturnal, secondary caVity-nesting tata)~white bursage (Ambrosia dumosa) series, bird that is a year-round resident throughout and in runnels and washes, the mixed-scrub much of western North America and Mexico series (Turner and Brown 1994). Temperatures (Marshall 1957, Phillips et al. 1964, AOU 1983, for the Arizona Upland and Lower Colorado Johnsgard 1988, Cannings and Angell 2001). -

ON 1196 NEW.Fm

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 25: 237–243, 2014 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society NON-RANDOM ORIENTATION IN WOODPECKER CAVITY ENTRANCES IN A TROPICAL RAIN FOREST Daniel Rico1 & Luis Sandoval2,3 1The University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska. 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Windsor, 401 Sunset Avenue, Windsor, ON, Canada, N9B3P4. 3Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San Pedro, San José, Costa Rica, CP 2090. E-mail: [email protected] Orientación no al azar de las entradas de las cavidades de carpinteros en un bosque tropical. Key words: Pale-billed Woodpecker, Campephilus guatemalensis, Chestnut-colored Woodpecker, Celeus castaneus, Lineated Woodpecker, Dryocopus lineatus, Black-cheeked Woodpecker, Melanerpes pucherani, Costa Rica, Picidae. INTRODUCTION tics such as vegetation coverage of the nesting substrate, surrounding vegetation, and forest Nest site selection play’s one of the main roles age (Aitken et al. 2002, Adkins Giese & Cuth- in the breeding success of birds, because this bert 2003, Sandoval & Barrantes 2006). Nest selection influences the survival of eggs, orientation also plays an important role in the chicks, and adults by inducing variables such breeding success of woodpeckers, because the as the microclimatic conditions of the nest orientation positively influences the microcli- and probability of being detected by preda- mate conditions inside the nest cavity (Hooge tors (Viñuela & Sunyer 1992). Although et al. 1999, Wiebe 2001), by reducing the woodpecker nest site selections are well estab- exposure to direct wind currents, rainfalls, lished, the majority of this information is and/or extreme temperatures (Ardia et al. based on temperate forest species and com- 2006). Cavity entrance orientation showed munities (Newton 1998, Cornelius et al. -

Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2013/744 ON THE COVER Hooded Oriole (Icterus cucullatus). Photo by Moez Ali. Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2013/744 Authors Moez Ali Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory 230 Cherry Street, Suite 150 Fort Collins, Colorado 80521 Kristen Beaupré National Park Service Sonoran Desert Network 7660 E. Broadway Blvd, Suite 303 Tucson, Arizona 85710 Patricia Valentine-Darby University of West Florida Department of Biology 11000 University Parkway Pensacola, Florida 32514 Chris White Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory 230 Cherry Street, Suite 150 Fort Collins, Colorado 80521 Project Contact Robert E. Bennetts National Park Service Southern Plains Network Capulin Volcano National Monument PO Box 40 Des Moines, New Mexico 88418 May 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colora- do, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource manage- ment, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. -

Global Trends in Woodpecker Cavity Entrance Orientation: Latitudinal and Continental Effects Suggest Regional Climate Influence Author(S): Lukas Landler, Michelle A

Global Trends in Woodpecker Cavity Entrance Orientation: Latitudinal and Continental Effects Suggest Regional Climate Influence Author(s): Lukas Landler, Michelle A. Jusino, James Skelton & Jeffrey R. Walters Source: Acta Ornithologica, 49(2):257-266. Published By: Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3161/173484714X687145 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3161/173484714X687145 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. ACTA ORNITHOLOGICA Vol. 49 (2014) No. 2 Global trends in woodpecker cavity entrance orientation: latitudinal and continental effects suggest regional climate influence Lukas LANDLER1*, Michelle A. JUSINO1,2, James SKELTON1 & Jeffrey R. WALTERS1 1Department of Biological Sciences, Virginia Tech, 1405 Perry Street, Blacksburg, Virginia, 24061, USA 2Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1550 Linden Drive, Madison, Wisconsin, 53706, USA *Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Landler L., Jusino M. -

History of the Common Rosefinch in Britain and Ireland, 1869-1996

HISTORY OF THE COMMON ROSEFINCH IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND, 1869-1996 D. I. M. WALLACE Common Rosefinch Carpodacus erythrinus (D. I. M. Wallace) ABSTRACT Forty-five years ago, the Scarlet Grosbeak Carpodacus erythrinus was one of those birds that (supposedly) you had to go to Fair Isle to see. It was there, on 13th September 1951, that I visually devoured my first dumpy, oddly amorphous but beady-eyed example, as it clumped about in the same crop as an immature Black-headed Bunting Emberiza melanocephala. Both were presented to me by the late Professor Maury Meiklejohn, with the nerve-wracking enjoinder ‘I can see the rosefinch’s bill and wingbars, Ian, but you will have to help with the bunting. I need to know its rump and vent colours. I’m colour blind.’ That night, the late Ken Williamson commented ‘Grosbeaks are classic drift migrants’ and I remember, too, some discussion between him and the other senior observers concerning the (then still unusual) cross-Baltic movements to Sweden in spring. Not for a moment, however, did they consider that the species would one day breed in Britain. In 1992, when the Common Rosefinch, as it is now called, bred successfully at Flamborough Head, East Yorkshire and on the Suffolk coast, its addition to the regular breeding birds of Britain seemed imminent. No such event has ensued. Since the late 1970s, the number of British and Irish records has grown so noticeably in spring that this trend, and particularly the 1992 influx, are likely to be associated with the much-increased breeding population of southern Fenno-Scandia. -

A Study of the House Finch

40 B•.ROTOLO,A Study of the House Finch. [Jan.Auk A STUDY OF THE HOUSE FINCH. BY W. H. BERGTOLD, M.D. Tus characteristic native bird of the cities and towns of Colorado is the HouseFinch (Carpodacus mexicanusfrontalis); notwithstand- ing its sweetand characteristicsong, it is commonlymistaken by the averagecitizen and visitorfor the EnglishSparrow. Previous to the advent of the English Sparrow in Denver (about 1894, accordingto the writer's notes)the only bird at all commonabout the buildingsof Denver was this finch. Before the presentextensive settlement of Colorado,the HouseFinch was, so far as one can gather from the reports of the various early exploringexpeditions, to be found mainly along the tree covered 'bottoms' of the larger streams,along the foot hills, to a small extent up the streamsinto the foot hills, and possiblyalong the streamsas they neared the east line of the state. For the past six years,the writer has systematicallyand par- ticularly studied this species,bearing in mind severalproblems concerningit; the data securedin this work is now publishedfor the first time. It seemsdesirable to sayhere that the writer aloneis responsible for eachand every note, observation,and conclusiongiven in the followingparagraphs, the samehaving been drawn entirely from his personalstudies: everythingherein followingis published without prejudiceto past observationsand conclusions. METHOD OF STUDY. Under this captionare includedthe usualgeneral observation of the bird wheneverseen in andabout the city, andspecial arrange- mentsat the officeand homeof the writer, designedto facilitate minuteobservations, and to })ringabout a moreintimate acquain- tance with the bird. The officeis on thesixth floor of a buildingsituated in the heart of the businessdistrict of Denver, and providedwith suitable foodand drinkingtrays on the windowsill. -

Pocket Guide to Common Nesting Birds Nestwatch.Org Northern

House Finch (Carpodacus mexicanus) House Finches nest in a variety of deciduous and coniferous trees as well as on cacti, rock ledges, and building ledges. WHEN TO LOOK WHERE TO FIND IT Habitats Desert Open Shrub Town Woodland Substrates Cliff or Live Tree In/On Rock Branch Building Source: Birds of North America Online Source: Birds of North America Online WHAT YOU’LL FIND NESTING STATISTICS Nest Type Chick Clutch Size Nest Height Incubation Period Brooding Period 15 ft 13–14 12–19 days days 23 1010 ftft CupCup AltricialAltricial 65 Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) The male and female mockingbird construct their nest together; the male usually begins the nest by building the outer foundation while the female finishes up the inner lining. WHEN TO LOOK WHERE TO FIND IT Habitats Shrub Town Substrates Live Tree Bush or Vine or Branch Shrub Tangle Source: Birds of North America Online Source: Birds of North America Online WHAT YOU’LL FIND NESTING STATISTICS Nest Type Chick Clutch Size Nest Height Incubation Period Brooding Period 10 ft 12–13 12–13 days days 2 3ft Cup Altricial 6 American Robin (Turdus migratorius) Females build their nests from the inside out, pressing dead grass and twigs into a layer of mud, forming a cup shape using the wrist of one wing. WHEN TO LOOK WHERE TO FIND IT Habitats Forest Open Shrub Town Woodland Substrates Ground Post, Pole, Live Tree or Platform Branch Source: Birds of North America Online Source: Birds of North America Online WHAT YOU’LL FIND NESTING STATISTICS Nest Type Chick Clutch Size Nest Height Incubation Period Brooding Period 25 ft 12–14 13 days days 3 10 ft Cup Altricial 5 159 Sapsucker Woods Road Ithaca, NY 14850 www.birds.cornell.edu Pocket Guide to Common Nesting Birds NestWatch.org What is NestWatch? Nest Monitoring Protocol NestWatch is a citizen-science project that monitors status • Find bird nests using the information in this guide and at and trends in the reproductive biology of birds across the NestWatch.org. -

Appendix F: Ecology F-2 Terrestrial Resources Tables Appendix F, Attachment 2

Appendix F: Ecology F-2 Terrestrial Resources Tables Appendix F, Attachment 2 Table F-2-1 2000-2005 Breeding Bird Atlas Results for Census Blocks Common name Scientific name Canada Goose Branta canadensis Mute Swan Cygnus olor Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Ring-necked Pheasant Phasianus colchicus Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo Double-crested Cormorant Phalacrocorax auritus Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias Green Heron Butorides virescens Black-crowned Night-Heron Nycticorax nycticorax Osprey* Pandion haliaetus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura Red-tailed Hawk Buteo jamaicensis Peregrine Falcon* Falco peregrinus Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius American Woodcock Scolopax minor Rock Pigeon Columba livia Mourning Dove Zenaida macroura Eastern Screech-Owl Megascops asio Chimney Swift Chaetura pelagica Belted Kingfisher Megaceryle alcyon Red-bellied Woodpecker Melanerpes carolinus Downy Woodpecker Picoides pubescens Hairy Woodpecker Picoides villosus Northern Flicker Colaptes auratus Pileated Woodpecker Dryocopus pileatus Eastern Wood-Pewee Contopus virens Willow Flycatcher Empidonax traillii Eastern Phoebe Sayornis phoebe Great Crested Flycatcher Myiarchus crinitus Eastern Kingbird Tyrannus tyrannus White-eyed Vireo Vireo griseus Yellow-throated Vireo Vireo flavifrons Warbling Vireo Vireo gilvus Red-eyed Vireo Vireo olivaceus Blue Jay Cyanocitta cristata American Crow Corvus brachyrhynchos Fish Crow Corvus ossifragus Tree Swallow Tachycineta bicolor Northern Rough-winged Swallow Stelgidopteryx serripennis Bank Swallow -

Life History Account for Gila Woodpecker

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group GILA WOODPECKER Melanerpes uropygialis Family: PICIDAE Order: PICIFORMES Class: AVES B297 Written by: M. Green Reviewed by: L. Mewaldt Edited by: R. Duke,D. Winkler DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY An uncommon to fairly common resident in southern California along the Colorado River, and locally near Brawley, Imperial Co. Occurs mostly in desert riparian and desert wash habitats, but also found in orchard-vineyard and urban habitats, particularly in shade trees and date palm groves. Formerly found in farm and ranchyards throughout the Imperial Valley, but most regularly now near Brawley. Numbers have declined greatly in southern California in recent decades (Remsen 1978, Garrett and Dunn 1981). SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Eats insects, mistletoe berries, cactus fruits, corn (Gilman 1915, Ehrlich et al. 1988), and occasionally contents of galls on cottonwood leaves, bird eggs, acorns, cactus pulp (Speich and Radke 1975). Gleans from trunks and branches of trees and shrubs. Cover: Cottonwoods and other desert riparian trees, shade trees, and date palms supply cover in California. Saguaros are important habitat elements outside of California, but are scarce within the state and are not so important. Reproduction: Nests in cavity in riparian tree or saguaro. Water: No data found. Characteristically forages and nests in riparian areas in California. Pattern: Groves of riparian trees, planted shade trees, and date palm orchards provide cover. SPECIES LIFE HISTORY Activity Patterns: Yearlong, diurnal activity. Seasonal Movements/Migration: Resident within California. May wander in nonbreeding seasons. There are 2 old records in southern, coastal California. -

House Finch (Carpodacus Mexicanus)1

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. WEC 253 Florida's Introduced Birds: House Finch (Carpodacus mexicanus)1 Steve A. Johnson and Jill Sox2 A wide variety of non-native birds have been introduced in Florida—perhaps as many as 200 species! Of these, at least 14 introduced species are considered established, according to various authorities, and some are now considered invasive and could have serious impacts in Florida. This fact sheet introduces the House Finch, and is one of a series of fact sheets about Florida's established non-native birds and their impacts on our native ecosystems, economy, and the quality of life of Floridians. For more information on Florida's introduced birds, how they got here, and the problems they cause, read "Florida's Introduced Birds: An Overview" (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/UW297) and the Figure 1. Male House Finch (Carpodacus mexicanus) other fact sheets in this series, Credits: Ken Thomas http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ long with a wingspan of 8–10 inches (20–25 cm) topic_series_floridas_introduced_birds. and weigh approximately 1 ounce (25 g). Both males and females have brown back and wing feathers with Species Description dark streaks and white tips, and their belly or The House Finch (Carpodacus mexicanus) is a underside is white and heavily streaked with brown. member of the finch family (Fringillidae), which are House Finches have black eyes, dark brown legs, and small, seed-eating songbirds. These sparrow-like a short, brown beak with an arched top edge. The birds are common visitors to backyard bird feeders.