History of the Common Rosefinch in Britain and Ireland, 1869-1996

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unsuitability of the House Finch As a Host of the Brown-Headed Cowbird’

The Condor 98:253-258 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1996 UNSUITABILITY OF THE HOUSE FINCH AS A HOST OF THE BROWN-HEADED COWBIRD’ DANIEL R. KOZLOVIC Department of Zoology, Universityof Toronto, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3G5, Canada RICHARD W. KNAPTON Long Point Waterfowl and WetlandsResearch Fund, P.O. Box 160, Port Rowan, Ontario NOE IMO, Canada JON C. BARLOW Department of Ornithology,Royal Ontario Museum, 100 Queens’ Park, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2C6, Canada and Department of Zoology, Universityof Toronto, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3G5, Canada Abstract. Brown-headedCowbirds (Molothrus ater) parasitized99 (24.4%)of 406 House Finch (Carpodacusmexicanus) nests observed at Barrie,Guelph, Orillia, and St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada,during the periods1983-1985 and 1990-1993.Hatching success of cow- bird eggswas 84.8%, but no cowbirdwas reared.Cowbird growth was severelyretarded; nestlingsrequired about twice as much time to accomplishthe sameamount of growth observedin nestsof otherhosts. Estimated final bodymass of nestlingcowbirds was about 22% lower than normal. Cowbirdnestlings survived on averageonly 3.2 days.Only one cowbirdfledged but died within one day. Lack of cowbirdsurvival in nestsof the House Finch appearsto be the resultof an inappropriatediet. We concludethat nestlingdiet may be importantin determiningcowbird choice of host. Key words: Brown-headed Cowbird; Molothrusater; House Finch; Carpodacusmexi- canus;brood parasitism; cowbirdsurvivorship; nestling diet. INTRODUCTION (Woods 1968). Like other members of the Car- The Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) is duelinae, House Finches are unusual among an obligate brood parasite that lays its eggsin cowbird hosts in that they feed their young pri- the nests of many host species, which provide marily plant material. -

§4-71-6.5 LIST of CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November

§4-71-6.5 LIST OF CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November 28, 2006 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Plesiopora FAMILY Tubificidae Tubifex (all species in genus) worm, tubifex PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Crustacea ORDER Anostraca FAMILY Artemiidae Artemia (all species in genus) shrimp, brine ORDER Cladocera FAMILY Daphnidae Daphnia (all species in genus) flea, water ORDER Decapoda FAMILY Atelecyclidae Erimacrus isenbeckii crab, horsehair FAMILY Cancridae Cancer antennarius crab, California rock Cancer anthonyi crab, yellowstone Cancer borealis crab, Jonah Cancer magister crab, dungeness Cancer productus crab, rock (red) FAMILY Geryonidae Geryon affinis crab, golden FAMILY Lithodidae Paralithodes camtschatica crab, Alaskan king FAMILY Majidae Chionocetes bairdi crab, snow Chionocetes opilio crab, snow 1 CONDITIONAL ANIMAL LIST §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Chionocetes tanneri crab, snow FAMILY Nephropidae Homarus (all species in genus) lobster, true FAMILY Palaemonidae Macrobrachium lar shrimp, freshwater Macrobrachium rosenbergi prawn, giant long-legged FAMILY Palinuridae Jasus (all species in genus) crayfish, saltwater; lobster Panulirus argus lobster, Atlantic spiny Panulirus longipes femoristriga crayfish, saltwater Panulirus pencillatus lobster, spiny FAMILY Portunidae Callinectes sapidus crab, blue Scylla serrata crab, Samoan; serrate, swimming FAMILY Raninidae Ranina ranina crab, spanner; red frog, Hawaiian CLASS Insecta ORDER Coleoptera FAMILY Tenebrionidae Tenebrio molitor mealworm, -

Mt. Tabor Park Breeding Bird Survey Results 2009

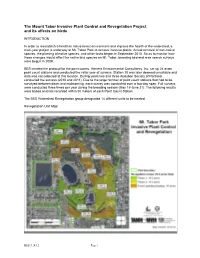

The Mount Tabor Invasive Plant Control and Revegetation Project and its affects on birds INTRODUCTION In order to reestablish a healthier native forest environment and improve the health of the watershed, a multi-year project is underway at Mt. Tabor Park to remove invasive plants. Actual removal of non-native species, the planting of native species, and other tasks began in September 2010. So as to monitor how these changes would affect the native bird species on Mt. Tabor, breeding bird and area search surveys were begun in 2009. BES created the protocol for the point counts. Herrera Environmental Consultants, Inc. set up 24 avian point count stations and conducted the initial year of surveys. Station 10 was later deemed unsuitable and data was not collected at this location. During years two and three Audubon Society of Portland conducted the surveys (2010 and 2011). Due to the large number of point count stations that had to be surveyed between dawn and midmorning, each survey was conducted over a two-day span. Full surveys were conducted three times per year during the breeding season (May 15-June 31). The following results were based on birds recorded within 50 meters of each Point Count Station. The BES Watershed Revegetation group designated 14 different units to be treated. Revegetation Unit Map: BES 3.14.12 Page 1 Point Count Station Location Map: The above map was created by Herrera and shows where the point count stations are located. Point Count Stations are fairly evenly dispersed around Mt. Tabor in a variety of habitats. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Phylogeography of Finches and Sparrows

In: Animal Genetics ISBN: 978-1-60741-844-3 Editor: Leopold J. Rechi © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF FINCHES AND SPARROWS Antonio Arnaiz-Villena*, Pablo Gomez-Prieto and Valentin Ruiz-del-Valle Department of Immunology, University Complutense, The Madrid Regional Blood Center, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Fringillidae finches form a subfamily of songbirds (Passeriformes), which are presently distributed around the world. This subfamily includes canaries, goldfinches, greenfinches, rosefinches, and grosbeaks, among others. Molecular phylogenies obtained with mitochondrial DNA sequences show that these groups of finches are put together, but with some polytomies that have apparently evolved or radiated in parallel. The time of appearance on Earth of all studied groups is suggested to start after Middle Miocene Epoch, around 10 million years ago. Greenfinches (genus Carduelis) may have originated at Eurasian desert margins coming from Rhodopechys obsoleta (dessert finch) or an extinct pale plumage ancestor; it later acquired green plumage suitable for the greenfinch ecological niche, i.e.: woods. Multicolored Eurasian goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) has a genetic extant ancestor, the green-feathered Carduelis citrinella (citril finch); this was thought to be a canary on phonotypical bases, but it is now included within goldfinches by our molecular genetics phylograms. Speciation events between citril finch and Eurasian goldfinch are related with the Mediterranean Messinian salinity crisis (5 million years ago). Linurgus olivaceus (oriole finch) is presently thriving in Equatorial Africa and was included in a separate genus (Linurgus) by itself on phenotypical bases. Our phylograms demonstrate that it is and old canary. Proposed genus Acanthis does not exist. Twite and linnet form a separate radiation from redpolls. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Goldfinches and Finch Food!

A Purple Finch (left) en- Frequently Asked Questions joys Sunflower Hearts and About Finch FOOD: an American goldfinch (right, in winter plumage) B i r d s - I - V i e w munches on a 50/50 blend Q. What do Finches eat? of Sunflower heart chips A. Finches utilize many small grass seeds and and Nyjer Seed . flower seed in nature and are built to shell tiny Frequently Asked Questions seeds easily. At Backyard Bird feeders they will Q. Do Goldfinches migrate in winter? FAQ consume Nyjer Seed (traditionally referred to as A. In much of the US, including the Mid- “thistle” in the bird feeding industry, but now west, Goldfinch are year-round residents. about more correctly referred to as “Nyjer”). They also There are areas of the US that only experi- consume Black Oil sunflower Seed and LOVE ence Goldfinch in the Winter and parts of Goldfinches and Sunflower HEARTS whether whole or in fine northern US and Canada only have them chips. In recent years, more and more backyard during breeding season. Check out the nota- Finch Food! birders are feeding Sunflower hearts (which ble difference between the Goldfinch’s does not have a shell) either alone or combined plumage in the winter and during breeding with the traditional Nyjer seed (which DOES season on the cover of this brochure! Q. What other finches can I see at feeders used by Goldfinch? A. Year-round House Finch as well as non- finch family birds like chickadees, tufted Titmouse, and Downy Woodpecker will en- joy your finch feeder. -

First Records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla Coelebs and European Greenfinch Carduelis Chloris from Lord Howe Island

83 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2004, 2I , 83- 85 First Records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris from Lord Howe Island GLENN FRASER 34 George Street, Horsham, Victoria 3400 Summary Details are given of the first records of two species of finch from Lord Howe Island: the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and the European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris. These records, from the early 1980s, have been quoted in several papers without the details hav ing been published. My Common Chaffinch records are the first for the species in Australian territory. Details of my records and of other published records of other European finch es on Lord Howe Island are listed, and speculation is made on the origin of these finches. Introduction This paper gives details of the first records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and the European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris for Lord Howe Island. The Common Chaffinch records are the first for any Australian territory and although often quoted (e.g. Boles 1988, Hutton 1991, Christidis & Boles 1994), the details have not yet been published. Other finches, the European Goldfinch C. carduelis and Common Redpoll C. fiammea, both rarely reported from Lord Howe Island, were also recorded at about the same time. Lord Howe Island (31 °32'S, 159°06'E) lies c. 800 km north-east of Sydney, N.S.W. It is 600 km from the nearest landfall in New South Wales, and 1200 km from New Zealand. Lord Howe Island is small (only 11 km long x 2.8 km wide) and dominated by two mountains, Mount Lidgbird and Mount Gower, the latter rising to 866 m above sea level. -

The Relationships of the Hawaiian Honeycreepers (Drepaninini) As Indicated by Dna-Dna Hybridization

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE HAWAIIAN HONEYCREEPERS (DREPANININI) AS INDICATED BY DNA-DNA HYBRIDIZATION CH^RrES G. SIBLEY AND Jo• E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--Twenty-twospecies of Hawaiian honeycreepers(Fringillidae: Carduelinae: Drepaninini) are known. Their relationshipsto other groups of passefineswere examined by comparing the single-copyDNA sequencesof the Apapane (Himationesanguinea) with those of 5 speciesof carduelinefinches, 1 speciesof Fringilla, 15 speciesof New World nine- primaried oscines(Cardinalini, Emberizini, Thraupini, Parulini, Icterini), and members of 6 other families of oscines(Turdidae, Monarchidae, Dicaeidae, Sylviidae, Vireonidae, Cor- vidae). The DNA-DNA hybridization data support other evidence indicating that the Hawaiian honeycreepersshared a more recent common ancestorwith the cardue!ine finches than with any of the other groupsstudied and indicate that this divergenceoccurred in the mid-Miocene, 15-20 million yr ago. The colonizationof the Hawaiian Islandsby the ancestralspecies that radiated to produce the Hawaiian honeycreeperscould have occurredat any time between 20 and 5 million yr ago. Becausethe honeycreeperscaptured so many ecologicalniches, however, it seemslikely that their ancestor was the first passefine to become established in the islands and that it arrived there at the time of, or soon after, its separationfrom the carduelinelineage. If so, this colonist arrived before the present islands from Hawaii to French Frigate Shoal were formed by the volcanic"hot-spot" now under the island of Hawaii. Therefore,the ancestral drepaninine may have colonizedone or more of the older Hawaiian Islandsand/or Emperor Seamounts,which also were formed over the "hot-spot" and which reachedtheir present positions as the result of tectonic crustal movement. -

Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2013/744 ON THE COVER Hooded Oriole (Icterus cucullatus). Photo by Moez Ali. Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2013/744 Authors Moez Ali Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory 230 Cherry Street, Suite 150 Fort Collins, Colorado 80521 Kristen Beaupré National Park Service Sonoran Desert Network 7660 E. Broadway Blvd, Suite 303 Tucson, Arizona 85710 Patricia Valentine-Darby University of West Florida Department of Biology 11000 University Parkway Pensacola, Florida 32514 Chris White Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory 230 Cherry Street, Suite 150 Fort Collins, Colorado 80521 Project Contact Robert E. Bennetts National Park Service Southern Plains Network Capulin Volcano National Monument PO Box 40 Des Moines, New Mexico 88418 May 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colora- do, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource manage- ment, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. -

Pinecrest Golf Course

Pinecrest Golf Course Birds on the Course In North America the Red-tailed Hawk is one of three species colloquially known as the “chicken hawk” or "hen hawk" even though chickens are not a major part of their diet. They were given this name in earlier times, when free-ranging chickens were preyed upon by first-year juveniles. They are also called buzzard hawks or red hawks. Red-tailed Hawks are easily recognized by their brick-red colored tails, from which its common name was derived. In the wild, they are expected to live for 10 -21 years. They reach reproductive maturity when they are about 3 years old. The Red-tailed Hawks is a bird of prey found in North and Central America, and in the West Indies. Throughout their range, they typically live in forests near open country or - depending on their range - in swamps, taigas and deserts. This species is legally protected in Canada, Mexico and the United States by the international Migratory Bird Treaty Act. In the United States, they are also protected by state, provincial and federal bird protection laws, making it illegal to keep hawks (without a permit) in captivity, or to Red-Tailed Hawk hunt them; disturb nests or eggs; even collecting their feathers is against the law. Red-Shouldered Hawk The Red-shouldered Sharp- Hawk is a medium-sized Hawk. A common Shinned forest-dwelling hawk of the East and California, Hawk the Red-shouldered Hawk favors woodlands near water. It is perhaps The sharp-shinned hawk is small with blue-gray upper parts and rufous bars on white the most vocal under parts. -

Examining Trends in Bird Populations Over 10 Years of Data from a Local Banding Station in the BC Lower Mainland

RES 500C - Vancouver Avian Research Centre (VARC) Examining trends in bird populations over 10 years of data from a local banding station in the BC Lower Mainland Authored by: Amy Liu, Carla Di Filippo, Erin Ryan April 2020 Table of contents ABSTRACT 2 RESEARCH REPORT 2 Introduction 2 Methods 4 Study area and data collection 4 Dataset management 5 Statistical Analysis 6 Results 8 Changes in local avian community through time 8 Changes in capture rates of individual species through time 11 Patterns associated with ecological guilds and their categories. 13 Discussion 16 Changes in local avian community through time 16 Changes in individual species through time 16 Trends associated with ecological guilds and their categories 19 Limitations and future research 20 Conclusion 21 SCIENCE COMMUNICATIONS 22 Education presentation 22 Social media 22 Facebook 22 Instagram 24 Twitter 25 GENERAL COMMUNICATIONS 26 2019 Annual report sample 26 Branded Powerpoint templates 27 Social media 27 Facebook 27 Instagram 28 Twitter 29 Target demographics 29 LIST OF APPENDICES 31 REFERENCES 32 1 ABSTRACT Bird monitoring programs provide the foundational data for programs that study and conserve birds. More than ever, with the uncertainty of climate change and increasing human impacts, research and monitoring to quantify species abundance are essential for our understanding of changing avian communities to guide successful conservation and management actions. This project examined 11 years (2009 - 2019) of bird banding data from a community banding station in Coquitlam, BC, Canada. The research approached three main questions: 1) Has the avian community changed over these years? 2) How have capture frequencies of individual species changed over time? 3) Can ecological factors explain the changes observed in the community and species of interest? Here, we have highlighted patterns in local abundance over time in the avian community, demonstrated case examples of decline and recovery in local species, and presented possible ecological factors that could be influencing these patterns.