A Study of the House Finch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unsuitability of the House Finch As a Host of the Brown-Headed Cowbird’

The Condor 98:253-258 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1996 UNSUITABILITY OF THE HOUSE FINCH AS A HOST OF THE BROWN-HEADED COWBIRD’ DANIEL R. KOZLOVIC Department of Zoology, Universityof Toronto, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3G5, Canada RICHARD W. KNAPTON Long Point Waterfowl and WetlandsResearch Fund, P.O. Box 160, Port Rowan, Ontario NOE IMO, Canada JON C. BARLOW Department of Ornithology,Royal Ontario Museum, 100 Queens’ Park, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2C6, Canada and Department of Zoology, Universityof Toronto, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3G5, Canada Abstract. Brown-headedCowbirds (Molothrus ater) parasitized99 (24.4%)of 406 House Finch (Carpodacusmexicanus) nests observed at Barrie,Guelph, Orillia, and St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada,during the periods1983-1985 and 1990-1993.Hatching success of cow- bird eggswas 84.8%, but no cowbirdwas reared.Cowbird growth was severelyretarded; nestlingsrequired about twice as much time to accomplishthe sameamount of growth observedin nestsof otherhosts. Estimated final bodymass of nestlingcowbirds was about 22% lower than normal. Cowbirdnestlings survived on averageonly 3.2 days.Only one cowbirdfledged but died within one day. Lack of cowbirdsurvival in nestsof the House Finch appearsto be the resultof an inappropriatediet. We concludethat nestlingdiet may be importantin determiningcowbird choice of host. Key words: Brown-headed Cowbird; Molothrusater; House Finch; Carpodacusmexi- canus;brood parasitism; cowbirdsurvivorship; nestling diet. INTRODUCTION (Woods 1968). Like other members of the Car- The Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) is duelinae, House Finches are unusual among an obligate brood parasite that lays its eggsin cowbird hosts in that they feed their young pri- the nests of many host species, which provide marily plant material. -

Mt. Tabor Park Breeding Bird Survey Results 2009

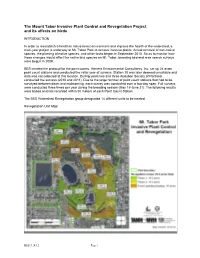

The Mount Tabor Invasive Plant Control and Revegetation Project and its affects on birds INTRODUCTION In order to reestablish a healthier native forest environment and improve the health of the watershed, a multi-year project is underway at Mt. Tabor Park to remove invasive plants. Actual removal of non-native species, the planting of native species, and other tasks began in September 2010. So as to monitor how these changes would affect the native bird species on Mt. Tabor, breeding bird and area search surveys were begun in 2009. BES created the protocol for the point counts. Herrera Environmental Consultants, Inc. set up 24 avian point count stations and conducted the initial year of surveys. Station 10 was later deemed unsuitable and data was not collected at this location. During years two and three Audubon Society of Portland conducted the surveys (2010 and 2011). Due to the large number of point count stations that had to be surveyed between dawn and midmorning, each survey was conducted over a two-day span. Full surveys were conducted three times per year during the breeding season (May 15-June 31). The following results were based on birds recorded within 50 meters of each Point Count Station. The BES Watershed Revegetation group designated 14 different units to be treated. Revegetation Unit Map: BES 3.14.12 Page 1 Point Count Station Location Map: The above map was created by Herrera and shows where the point count stations are located. Point Count Stations are fairly evenly dispersed around Mt. Tabor in a variety of habitats. -

Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2013/744 ON THE COVER Hooded Oriole (Icterus cucullatus). Photo by Moez Ali. Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2013/744 Authors Moez Ali Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory 230 Cherry Street, Suite 150 Fort Collins, Colorado 80521 Kristen Beaupré National Park Service Sonoran Desert Network 7660 E. Broadway Blvd, Suite 303 Tucson, Arizona 85710 Patricia Valentine-Darby University of West Florida Department of Biology 11000 University Parkway Pensacola, Florida 32514 Chris White Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory 230 Cherry Street, Suite 150 Fort Collins, Colorado 80521 Project Contact Robert E. Bennetts National Park Service Southern Plains Network Capulin Volcano National Monument PO Box 40 Des Moines, New Mexico 88418 May 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colora- do, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource manage- ment, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. -

History of the Common Rosefinch in Britain and Ireland, 1869-1996

HISTORY OF THE COMMON ROSEFINCH IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND, 1869-1996 D. I. M. WALLACE Common Rosefinch Carpodacus erythrinus (D. I. M. Wallace) ABSTRACT Forty-five years ago, the Scarlet Grosbeak Carpodacus erythrinus was one of those birds that (supposedly) you had to go to Fair Isle to see. It was there, on 13th September 1951, that I visually devoured my first dumpy, oddly amorphous but beady-eyed example, as it clumped about in the same crop as an immature Black-headed Bunting Emberiza melanocephala. Both were presented to me by the late Professor Maury Meiklejohn, with the nerve-wracking enjoinder ‘I can see the rosefinch’s bill and wingbars, Ian, but you will have to help with the bunting. I need to know its rump and vent colours. I’m colour blind.’ That night, the late Ken Williamson commented ‘Grosbeaks are classic drift migrants’ and I remember, too, some discussion between him and the other senior observers concerning the (then still unusual) cross-Baltic movements to Sweden in spring. Not for a moment, however, did they consider that the species would one day breed in Britain. In 1992, when the Common Rosefinch, as it is now called, bred successfully at Flamborough Head, East Yorkshire and on the Suffolk coast, its addition to the regular breeding birds of Britain seemed imminent. No such event has ensued. Since the late 1970s, the number of British and Irish records has grown so noticeably in spring that this trend, and particularly the 1992 influx, are likely to be associated with the much-increased breeding population of southern Fenno-Scandia. -

Pocket Guide to Common Nesting Birds Nestwatch.Org Northern

House Finch (Carpodacus mexicanus) House Finches nest in a variety of deciduous and coniferous trees as well as on cacti, rock ledges, and building ledges. WHEN TO LOOK WHERE TO FIND IT Habitats Desert Open Shrub Town Woodland Substrates Cliff or Live Tree In/On Rock Branch Building Source: Birds of North America Online Source: Birds of North America Online WHAT YOU’LL FIND NESTING STATISTICS Nest Type Chick Clutch Size Nest Height Incubation Period Brooding Period 15 ft 13–14 12–19 days days 23 1010 ftft CupCup AltricialAltricial 65 Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) The male and female mockingbird construct their nest together; the male usually begins the nest by building the outer foundation while the female finishes up the inner lining. WHEN TO LOOK WHERE TO FIND IT Habitats Shrub Town Substrates Live Tree Bush or Vine or Branch Shrub Tangle Source: Birds of North America Online Source: Birds of North America Online WHAT YOU’LL FIND NESTING STATISTICS Nest Type Chick Clutch Size Nest Height Incubation Period Brooding Period 10 ft 12–13 12–13 days days 2 3ft Cup Altricial 6 American Robin (Turdus migratorius) Females build their nests from the inside out, pressing dead grass and twigs into a layer of mud, forming a cup shape using the wrist of one wing. WHEN TO LOOK WHERE TO FIND IT Habitats Forest Open Shrub Town Woodland Substrates Ground Post, Pole, Live Tree or Platform Branch Source: Birds of North America Online Source: Birds of North America Online WHAT YOU’LL FIND NESTING STATISTICS Nest Type Chick Clutch Size Nest Height Incubation Period Brooding Period 25 ft 12–14 13 days days 3 10 ft Cup Altricial 5 159 Sapsucker Woods Road Ithaca, NY 14850 www.birds.cornell.edu Pocket Guide to Common Nesting Birds NestWatch.org What is NestWatch? Nest Monitoring Protocol NestWatch is a citizen-science project that monitors status • Find bird nests using the information in this guide and at and trends in the reproductive biology of birds across the NestWatch.org. -

Appendix F: Ecology F-2 Terrestrial Resources Tables Appendix F, Attachment 2

Appendix F: Ecology F-2 Terrestrial Resources Tables Appendix F, Attachment 2 Table F-2-1 2000-2005 Breeding Bird Atlas Results for Census Blocks Common name Scientific name Canada Goose Branta canadensis Mute Swan Cygnus olor Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Ring-necked Pheasant Phasianus colchicus Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo Double-crested Cormorant Phalacrocorax auritus Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias Green Heron Butorides virescens Black-crowned Night-Heron Nycticorax nycticorax Osprey* Pandion haliaetus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura Red-tailed Hawk Buteo jamaicensis Peregrine Falcon* Falco peregrinus Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius American Woodcock Scolopax minor Rock Pigeon Columba livia Mourning Dove Zenaida macroura Eastern Screech-Owl Megascops asio Chimney Swift Chaetura pelagica Belted Kingfisher Megaceryle alcyon Red-bellied Woodpecker Melanerpes carolinus Downy Woodpecker Picoides pubescens Hairy Woodpecker Picoides villosus Northern Flicker Colaptes auratus Pileated Woodpecker Dryocopus pileatus Eastern Wood-Pewee Contopus virens Willow Flycatcher Empidonax traillii Eastern Phoebe Sayornis phoebe Great Crested Flycatcher Myiarchus crinitus Eastern Kingbird Tyrannus tyrannus White-eyed Vireo Vireo griseus Yellow-throated Vireo Vireo flavifrons Warbling Vireo Vireo gilvus Red-eyed Vireo Vireo olivaceus Blue Jay Cyanocitta cristata American Crow Corvus brachyrhynchos Fish Crow Corvus ossifragus Tree Swallow Tachycineta bicolor Northern Rough-winged Swallow Stelgidopteryx serripennis Bank Swallow -

House Finch (Carpodacus Mexicanus)1

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. WEC 253 Florida's Introduced Birds: House Finch (Carpodacus mexicanus)1 Steve A. Johnson and Jill Sox2 A wide variety of non-native birds have been introduced in Florida—perhaps as many as 200 species! Of these, at least 14 introduced species are considered established, according to various authorities, and some are now considered invasive and could have serious impacts in Florida. This fact sheet introduces the House Finch, and is one of a series of fact sheets about Florida's established non-native birds and their impacts on our native ecosystems, economy, and the quality of life of Floridians. For more information on Florida's introduced birds, how they got here, and the problems they cause, read "Florida's Introduced Birds: An Overview" (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/UW297) and the Figure 1. Male House Finch (Carpodacus mexicanus) other fact sheets in this series, Credits: Ken Thomas http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ long with a wingspan of 8–10 inches (20–25 cm) topic_series_floridas_introduced_birds. and weigh approximately 1 ounce (25 g). Both males and females have brown back and wing feathers with Species Description dark streaks and white tips, and their belly or The House Finch (Carpodacus mexicanus) is a underside is white and heavily streaked with brown. member of the finch family (Fringillidae), which are House Finches have black eyes, dark brown legs, and small, seed-eating songbirds. These sparrow-like a short, brown beak with an arched top edge. The birds are common visitors to backyard bird feeders. -

Bird List of San Bernardino Ranch in Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico

Bird List of San Bernardino Ranch in Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico Melinda Cárdenas-García and Mónica C. Olguín-Villa Universidad de Sonora, Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico Abstract—Interest and investigation of birds has been increasing over the last decades due to the loss of their habitats, and declination and fragmentation of their populations. San Bernardino Ranch is located in the desert grassland region of northeastern Sonora, México. Over the last decade, restoration efforts have tried to address the effects of long deteriorating economic activities, like agriculture and livestock, that used to take place there. The generation of annual lists of the wildlife (flora and fauna) will be important information as we monitor the progress of restoration of this area. As part of our professional training, during the summer and winter (2011-2012) a taxonomic list of bird species of the ranch was made. During this season, a total of 85 species and 65 genera, distributed over 30 families were found. We found that five species are on a risk category in NOM-059-ECOL-2010 and 76 species are included in the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It will be important to continue this type of study in places that are at- tempting restoration and conservation techniques. We have observed a huge change, because of restoration activities, in the lands in the San Bernardino Ranch. Introduction migratory (Villaseñor-Gómez et al., 2010). Twenty-eight of those species are considered at risk on a global scale, and are included in Birds represent one of the most remarkable elements of our en- the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature vironment, because they’re easy to observe and it’s possible to find (IUCN). -

Half a Century of Ornithology in Texas: the Legacy of Dr

Half a Century of Ornithology in Texas: the Legacy of Dr. Keith Arnold Edited by Daniel M. Brooks Miscellaneous Publications of The Houston Museum of Natural Science, Number 7 Ecology, behavior and reproduction of an introduced population of Scaly-breasted Munias (Lonchura punctulata ) in Houston, Texas Alyssa R. Conn 1, Lynn Chamberlain 2 and Daniel M. Brooks 1 1 Houston Museum of Natural Science, Department of Vertebrate Zoology, 5555 Hermann Park Drive, Houston, Texas 77030-1799; e-mail: [email protected] 2 AECOM, 19219 Katy Freeway, Suite 100, Houston, TX 77094 Abstract - Results of a citizen-science project are reported to better understand potential impacts of an introduced population of Scaly-breasted Munias ( Lonchura punctulata ) in Houston, Texas. Houston records of munias accounted for 96% of all sightings in Texas. Nearly two-thirds of munias are found in urban habitats, with the remainder in more natural areas, especially parkland. A globose-shaped nest is built with young raised between early April - late September, and several nesting events are described. Munias are non-migratory, with flock size averaging 6.1 (range = 1-30), and three larger ‘mega-flocks’ are described. Munias are completely unaggressive towards other species and are observed foraging at feeders with 22 other species, of which 32% are other introduced species. The species most frequently associated with munias are House Finches ( Haemorhous mexicanus ) and American Goldfinches ( Spinus tristis ) which combined represented over one-half of all associations. Frequent behaviors included foraging (38%), vocalizing (24%), and perching (16%). The most common of the 25 species of plants used for perching are oak trees ( Quercus sp. -

House Finch Feeder of the Fledglings

1125 W 3300 S, South Salt Lake, UT 84119 | www.jordanrivernaturecenter.org House Finch feeder of the fledglings. Females can lay anywhere Haemorhous mexicanus from 2-6 eggs per clutch, laying only one egg per day. The incubation period is 12-14 days. FEEDING AND HABITS House finches eat exclusively plant material like seeds, buds, and fruits from a variety of plants, including poison oak! At backyard bird feeders they will eat black oil sunflower seeds and thistle (nyjer) seed. ADAPTATIONS ● Their thick strong beak allows for finches to crack open tough seed shells. ● House finches can be relatively aggressive toward other birds and are known to drive other DESCRIPTION birds away from feeders. House finches are small-bodied birds with short ● They are able to make nests nearly anywhere so wings and a relatively long tail. They have large beaks house finches can live in almost any for their body size and flat heads. Males are red environment. around the face and upper breast with a streaked ECOLOGY AND STATUS brown back and tail and belly. The females have a brown back and indistinct head and a streaked House finches are originally native to Mexico and the brown and white belly. southwestern U.S. However, they were brought to the eastern U.S. for the pet trade and ended up RANGE being released. They were able to adapt easily to House finches are native to the western United their new environment and spread rapidly across the States and were introduced in the eastern U.S. in the U.S. -

The Nesting Biology of the House Finch in Honolulu, Hawaii

WESTERN BIRDS Volume 6, Number 2, 1975 THE NESTING BIOLOGY OF THE HOUSE FINCH IN HONOLULU, HAWAII LAWRENCE T. HIRAI, Department of Zoology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 The House Finch, ½arpodacusmexicanus frontalis (Say), is a small seed-eatingpassefine found throughout western North America. It was introduced to Hawaii, probably from San Franciscoas an escapedcage- bird, prior to 1870 (Grinnell 1911). Today it is found on all the main Hawaiian islands. This was a field study of the nesting biology of the House Finch from January 1972 through July 1974, coveringthree nestingseasons. Some of the findingsare discussedin relation to what is known about HouseFinch populationsin North America. METHODS AND STUDY SITE Most of the study consistedof field observations,with almost daily checksof nests. Measurementswere madeusing a caliper,ruler, or tape measure.Weights were obtainedusing Pesola scales. To facilitate future identification, eggswere marked with a black "Shatpie" pen; nestlings were marked in 1972 with red nail polish, but in 1973 and 1974 with a red Shatpie pen, which provedmore satisfactory. Nestlingsnear fledg- ing and adults were bandedwith U.S. Fish and Wildlife Servicemetal bandsand one or two plasticbands in different color combinations.Un- less otherwise indicated calculations are in the form mean + one stan- dard deviation. The 0.05 value is consideredthe level of rejection. The study site was confined to the University of Hawaii 0.4 km' main campus,located in Manoa Valley, a residentialarea in Honolulu. WesternBirds 6:33-44, 1975 33 HOUSE FINCH The House Finch is one of about 15 bird speciesfound on or near the campus. -

Bird Checklist for Saguaro National Park: Rincon Mountain District

he Rincon Mountain District (RMD) of Saguaro √ Common name A H S √ Common name A H S √ Common name A H S TNational Park is ecologically diverse—a quality that is DUCKS AND GEESE whiskered screech-owl U WC,F S olive-sided fycatcher R Ri,D,WC,F M refected in this bird list of over 200 species. The Rincon mallard O Ri,D Y great horned owl U Ri,D,WC,F Y greater pewee C WC,F S Mountains are part of the Madrean Archipelago of “Sky TURKEYS AND QUAIL northern pygmy-owl R WC,F Y western wood-pewee C Ri,D,WC S Islands,” where the Rocky Mountains of the U.S. meet scaled quail R D,WC Y cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl O Ri,D Y willow fycatcher O Ri M Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental. The ranges of many subtropical plant and animal species (e.g., sulphur-bel- Gambel’s quail A Ri,D,WC Y elf owl C Ri,D,WC S Hammond’s fycatcher U Ri,D,WC,F M lied fycatcher, elegant trogon) reach their northernmost Montezuma quail U WC Y burrowing owl O D M gray fycatcher U Ri,D,WC W extent here. The RMD also lies at the interface of the wild turkey U Ri,WC,F Y Mexican spotted owl R WC,F Y dusky fycatcher R Ri,D,WC,F M Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts and includes biological BITTERNS, HERONS AND EGRETS long-eared owl R Ri,D,WC,F M Pacifc-slope fycatcher U Ri,D,WC M elements from both.