Half a Century of Ornithology in Texas: the Legacy of Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unsuitability of the House Finch As a Host of the Brown-Headed Cowbird’

The Condor 98:253-258 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1996 UNSUITABILITY OF THE HOUSE FINCH AS A HOST OF THE BROWN-HEADED COWBIRD’ DANIEL R. KOZLOVIC Department of Zoology, Universityof Toronto, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3G5, Canada RICHARD W. KNAPTON Long Point Waterfowl and WetlandsResearch Fund, P.O. Box 160, Port Rowan, Ontario NOE IMO, Canada JON C. BARLOW Department of Ornithology,Royal Ontario Museum, 100 Queens’ Park, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2C6, Canada and Department of Zoology, Universityof Toronto, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3G5, Canada Abstract. Brown-headedCowbirds (Molothrus ater) parasitized99 (24.4%)of 406 House Finch (Carpodacusmexicanus) nests observed at Barrie,Guelph, Orillia, and St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada,during the periods1983-1985 and 1990-1993.Hatching success of cow- bird eggswas 84.8%, but no cowbirdwas reared.Cowbird growth was severelyretarded; nestlingsrequired about twice as much time to accomplishthe sameamount of growth observedin nestsof otherhosts. Estimated final bodymass of nestlingcowbirds was about 22% lower than normal. Cowbirdnestlings survived on averageonly 3.2 days.Only one cowbirdfledged but died within one day. Lack of cowbirdsurvival in nestsof the House Finch appearsto be the resultof an inappropriatediet. We concludethat nestlingdiet may be importantin determiningcowbird choice of host. Key words: Brown-headed Cowbird; Molothrusater; House Finch; Carpodacusmexi- canus;brood parasitism; cowbirdsurvivorship; nestling diet. INTRODUCTION (Woods 1968). Like other members of the Car- The Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) is duelinae, House Finches are unusual among an obligate brood parasite that lays its eggsin cowbird hosts in that they feed their young pri- the nests of many host species, which provide marily plant material. -

Mt. Tabor Park Breeding Bird Survey Results 2009

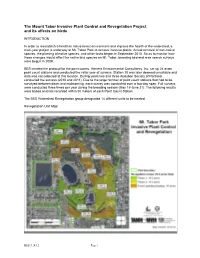

The Mount Tabor Invasive Plant Control and Revegetation Project and its affects on birds INTRODUCTION In order to reestablish a healthier native forest environment and improve the health of the watershed, a multi-year project is underway at Mt. Tabor Park to remove invasive plants. Actual removal of non-native species, the planting of native species, and other tasks began in September 2010. So as to monitor how these changes would affect the native bird species on Mt. Tabor, breeding bird and area search surveys were begun in 2009. BES created the protocol for the point counts. Herrera Environmental Consultants, Inc. set up 24 avian point count stations and conducted the initial year of surveys. Station 10 was later deemed unsuitable and data was not collected at this location. During years two and three Audubon Society of Portland conducted the surveys (2010 and 2011). Due to the large number of point count stations that had to be surveyed between dawn and midmorning, each survey was conducted over a two-day span. Full surveys were conducted three times per year during the breeding season (May 15-June 31). The following results were based on birds recorded within 50 meters of each Point Count Station. The BES Watershed Revegetation group designated 14 different units to be treated. Revegetation Unit Map: BES 3.14.12 Page 1 Point Count Station Location Map: The above map was created by Herrera and shows where the point count stations are located. Point Count Stations are fairly evenly dispersed around Mt. Tabor in a variety of habitats. -

Invasive Trees of Georgia Pub10-14

Pub. No. 39 October 2016 Invasive Trees of Georgia by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia Georgia has many species of trees. Some are native trees and some have been introduced from outside the state, nation, or continent. Most of Georgia’s trees are well- behaved and easily develop into sustainable shade and street trees. A few tree species have an extrodinary ability to upsurp resources and take over sites from other plants. These trees are called invasive because they effectively invade sites, many times eliminat- ing other species of plants. There are a few tree species native to Georgia which are considered invasive in other parts of the country. These native invasives, may be well-behaved in Georgia, but reproduce and take over sites elsewhere, and so have gained an invasive status from at least one other invasive species list. Table 1. There are hundreds of trees which have been introduced to Georgia landscapes. Some of these exotic / naturalized trees are considered invasive. The selected list of Georgia invasive trees listed here are notorious for growing rampantly and being difficult to eradicate. Table 2. Table 1: Native trees considered invasive in other parts of the country. scientific name common name scientific name common name Acacia farnesiana sweet acacia Myrica cerifera Southern bayberry Acer negundo boxelder Pinus taeda loblolly pine Acer rubrum red maple Populus deltoides Eastern cottonwood Fraxinus americana white ash Prunus serotina black cherry Fraxinus pennsylvanica green ash Robinia pseudoacacia black locust Gleditsia triacanthos honeylocust Toxicodendron vernix poison sumac Juniperus virginiana eastern redcedar The University of Georgia is committed to principles of equal opportunity and affirmative action. -

EKOKIDS: SCHOOLYARD NATURE GUIDES Birds

EKOKIDS:SCHOOLYARD NATURE GUIDES Trees Mammals Invertebrates Reptiles & Birds Amphibians EKOKIDS: SCHOOLYARD NATURE GUIDES Birds Birds are common visitors to schools, neighborhoods, parks, and other public places. Their diversity, bright colors, cheerful songs, and daytime habits make them great for engaging children and adults in nature study. Birds are unique among animals. All birds have feathers, wings, and beaks. They are found around the world, from ice-covered Antarctica to steamy jungles, from dry deserts to windy mountaintops, and from freshwater rivers to salty oceans. This booklet shares some information on just a few of the nearly 10,000 bird species that can be found worldwide. How many of these birds can you find in your part of the planet? Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) DESCRIPTION • Other names: redbird, common cardinal • Medium-sized songbird in the cardinal family • Males: bright red feathers, black face masks • Females: light brown feathers, gray face masks • Males and females: reddish-orange bills • Length: 8¾ inches; wingspan: 12 inches HABITAT The northern cardinal can be found throughout the Birds eastern U.S. This native species favors open areas with brushy habitat, including neighborhoods and NORTHERN CARDINAL suburban areas. FUN FACT EKOKIDS: SCHOOLYARD NATURE GUIDES Northern cardinals mate for life. When courting, the Mississippi State University Extension Service male feeds the female beak-to-beak. H ouse Finch (Haemorhous mexicanus) DESCRIPTION • Other name: rosefinch • Length: 6 inches; wingspan: 9½ inches • Males: bright, orange-red face and breast; streaky, gray-brown wings and tail • Females: overall gray-brown; no bright red color HABITAT The house finch is not native to the southeastern U.S. -

State of the Park Report, Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, Georgia

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior State of the Park Report Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park Georgia November 2013 National Park Service. 2013. State of the Park Report for Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park. State of the Park Series No. 8. National Park Service, Washington, D.C. On the cover: Civil War cannon and field of flags at Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park. Disclaimer. This State of the Park report summarizes the current condition of park resources, visitor experience, and park infrastructure as assessed by a combination of available factual information and the expert opinion and professional judgment of park staff and subject matter experts. The internet version of this report provides the associated workshop summary report and additional details and sources of information about the findings summarized in the report, including references, accounts on the origin and quality of the data, and the methods and analytic approaches used in data collection and assessments of condition. This report provides evaluations of status and trends based on interpretation by NPS scientists and managers of both quantitative and non- quantitative assessments and observations. Future condition ratings may differ from findings in this report as new data and knowledge become available. The park superintendent approved the publication of this report. Executive Summary The mission of the National Park Service is to preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of national parks for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations. NPS Management Policies (2006) state that “The Service will also strive to ensure that park resources and values are passed on to future generations in a condition that is as good as, or better than, the conditions that exist today.” As part of the stewardship of national parks for the American people, the NPS has begun to develop State of the Park reports to assess the overall status and trends of each park’s resources. -

Alarm Calls of Tufted Titmice Convey Information About Predator Size and Threat Downloaded from Jason R

Behavioral Ecology doi:10.1093/beheco/arq086 Advance Access publication 27 June 2010 Alarm calls of tufted titmice convey information about predator size and threat Downloaded from Jason R. Courter and Gary Ritchison Department of Biological Sciences, Eastern Kentucky University, Moore 235, 521 Lancaster Ave., Richmond, KY 40475, USA Many birds utter alarm calls when they encounter predators, and previous work has revealed that variation in the characteristics http://beheco.oxfordjournals.org of the alarm, or ‘‘chick-a-dee,’’ calls of black-capped (Poecile atricapilla) and Carolina (P. carolinensis) chickadees conveys infor- mation about predator size and threat. Little is known, however, about possible information conveyed by the similar ‘‘chick-a-dee’’ alarm call of tufted titmice (Baeolophus bicolor). During the winters of 2008 and 2009, free-ranging flocks (N ¼ 8) of tufted titmice were presented with models of several species of raptors that varied in size, and titmice responses were monitored. Smaller, higher threat predators (e.g., eastern screech-owl, Megascops asio) elicited longer mobbing bouts and alarm calls with more notes (D-notes) than larger lower threat predators (e.g., red-tailed hawk, Buteo jamaicensis). During playback experiments, titmice took longer to return to feeding after playbacks of alarm calls given in response to a small owl than to playbacks given in response to a large hawk or a robin (control). Like chickadees, titmice appear to utter alarm calls that convey information about predator size and threat. Titmice, however, appear to cue in on the total number of D-notes given per unit time instead of the number of D-notes per alarm call. -

Waxmyrtle-- a Shrub for a Natural Riparian Buffer

Waxmyrtle-- A Shrub for a Natural Riparian Buffer By Susan Camp When you live on a tidal creek or river, as do many of us on the Middle Peninsula, you bear a special responsibility to maintain a healthy interface between land and water. The plants that grow along a shoreline help to protect the adjacent waterway from erosion and pollutants, and they provide valuable habitat for the wildlife that live and feed along the banks. Jim and I are fortunate to live on property that was left in a natural state by the previous owners, and we have maintained the banks for 25 years with a minimum amount of labor and no expense. The native trees, shrubs, and grasses along the water’s edge maintain themselves with minor pruning of dead wood, trimming of greenbriers, and eradication of poison ivy. One of my favorite native shrubs is waxmyrtle (Myrica cerifera or Morella cerifera), also called southern waxmyrtle or southern bayberry. Waxmyrtle is a small tree or large, multi-trunked, fast- growing shrub, depending on how it is pruned. Waxmyrtle produces numerous suckers that lend the shrub an irregular, leggy appearance, but it can be maintained with a single trunk. Waxmyrtle is found from New Jersey south to Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, and west to Texas and Oklahoma, surviving in a wide range of environments from wet swamps to elevated forestland, although it is most often found in marshes and along tidal creeks and stream banks. The shrub grows well in USDA Hardiness Zones 6b to 11. It is evergreen where winters are mild, but is classified as semi-evergreen in colder environments, which means it will lose its leaves when the temperature drops below 0 F. -

Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2013/744 ON THE COVER Hooded Oriole (Icterus cucullatus). Photo by Moez Ali. Landbird Monitoring in the Sonoran Desert Network 2012 Annual Report Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SODN/NRTR—2013/744 Authors Moez Ali Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory 230 Cherry Street, Suite 150 Fort Collins, Colorado 80521 Kristen Beaupré National Park Service Sonoran Desert Network 7660 E. Broadway Blvd, Suite 303 Tucson, Arizona 85710 Patricia Valentine-Darby University of West Florida Department of Biology 11000 University Parkway Pensacola, Florida 32514 Chris White Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory 230 Cherry Street, Suite 150 Fort Collins, Colorado 80521 Project Contact Robert E. Bennetts National Park Service Southern Plains Network Capulin Volcano National Monument PO Box 40 Des Moines, New Mexico 88418 May 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colora- do, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource manage- ment, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. -

Texas Big Tree Registry a List of the Largest Trees in Texas Sponsored by Texas a & M Forest Service

Texas Big Tree Registry A list of the largest trees in Texas Sponsored by Texas A & M Forest Service Native and Naturalized Species of Texas: 320 ( D indicates species naturalized to Texas) Common Name (also known as) Latin Name Remarks Cir. Threshold acacia, Berlandier (guajillo) Senegalia berlandieri Considered a shrub by B. Simpson 18'' or 1.5 ' acacia, blackbrush Vachellia rigidula Considered a shrub by Simpson 12'' or 1.0 ' acacia, Gregg (catclaw acacia, Gregg catclaw) Senegalia greggii var. greggii Was named A. greggii 55'' or 4.6 ' acacia, Roemer (roundflower catclaw) Senegalia roemeriana 18'' or 1.5 ' acacia, sweet (huisache) Vachellia farnesiana 100'' or 8.3 ' acacia, twisted (huisachillo) Vachellia bravoensis Was named 'A. tortuosa' 9'' or 0.8 ' acacia, Wright (Wright catclaw) Senegalia greggii var. wrightii Was named 'A. wrightii' 70'' or 5.8 ' D ailanthus (tree-of-heaven) Ailanthus altissima 120'' or 10.0 ' alder, hazel Alnus serrulata 18'' or 1.5 ' allthorn (crown-of-thorns) Koeberlinia spinosa Considered a shrub by Simpson 18'' or 1.5 ' anacahuita (anacahuite, Mexican olive) Cordia boissieri 60'' or 5.0 ' anacua (anaqua, knockaway) Ehretia anacua 120'' or 10.0 ' ash, Carolina Fraxinus caroliniana 90'' or 7.5 ' ash, Chihuahuan Fraxinus papillosa 12'' or 1.0 ' ash, fragrant Fraxinus cuspidata 18'' or 1.5 ' ash, green Fraxinus pennsylvanica 120'' or 10.0 ' ash, Gregg (littleleaf ash) Fraxinus greggii 12'' or 1.0 ' ash, Mexican (Berlandier ash) Fraxinus berlandieriana Was named 'F. berlandierana' 120'' or 10.0 ' ash, Texas Fraxinus texensis 60'' or 5.0 ' ash, velvet (Arizona ash) Fraxinus velutina 120'' or 10.0 ' ash, white Fraxinus americana 100'' or 8.3 ' aspen, quaking Populus tremuloides 25'' or 2.1 ' baccharis, eastern (groundseltree) Baccharis halimifolia Considered a shrub by Simpson 12'' or 1.0 ' baldcypress (bald cypress) Taxodium distichum Was named 'T. -

Georgia Native Trees Considered Invasive in Other Parts of the Country. Scientific Name Common Name Scientific Name Common Name

Invasive Trees of Georgia Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care, Warnell School, UGA Georgia has many species of trees. Some are native trees and some have been introduced from outside the state, nation, or continent. Most of Georgia’s trees are well-behaved and easily develop into sustainable shade and street trees. A few tree species have an extrodinary ability to upsurp resources and take over sites from other plants. These trees are called invasive because they effectively invade sites, many times eliminating other species of plants. There are a few tree species native to Georgia which are considered invasive in other parts of the country. These native invasives, may be well-behaved in Georgia, but reproduce and take over sites elsewhere, and so have gained an invasive status from at least one other invasive species list. Table 1. There are hundreds of trees which have been introduced to Georgia landscapes. Some of these exotic / naturalized trees are considered invasive. The selected list of Georgia invasive trees listed here are notorious for growing rampantly and being diffi- cult to eradicate. Table 2. They should not be planted. Table 1: Georgia native trees considered invasive in other parts of the country. scientific name common name scientific name common name Acacia farnesiana sweet acacia Myrica cerifera Southern bayberry Acer negundo boxelder Pinus taeda loblolly pine Acer rubrum red maple Populus deltoides Eastern Fraxinus americana white ash cottonwood Fraxinus pennsylvanica green ash Prunus serotina black cherry Gleditsia triacanthos honeylocust Robinia pseudoacacia black locust Juniperus virginiana eastern Toxicodendron vernix poison sumac redcedar Table 2: Introduced (exotic) tree / shrub species found in Georgia listed at a regional / national level as being ecologically invasive. -

History of the Common Rosefinch in Britain and Ireland, 1869-1996

HISTORY OF THE COMMON ROSEFINCH IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND, 1869-1996 D. I. M. WALLACE Common Rosefinch Carpodacus erythrinus (D. I. M. Wallace) ABSTRACT Forty-five years ago, the Scarlet Grosbeak Carpodacus erythrinus was one of those birds that (supposedly) you had to go to Fair Isle to see. It was there, on 13th September 1951, that I visually devoured my first dumpy, oddly amorphous but beady-eyed example, as it clumped about in the same crop as an immature Black-headed Bunting Emberiza melanocephala. Both were presented to me by the late Professor Maury Meiklejohn, with the nerve-wracking enjoinder ‘I can see the rosefinch’s bill and wingbars, Ian, but you will have to help with the bunting. I need to know its rump and vent colours. I’m colour blind.’ That night, the late Ken Williamson commented ‘Grosbeaks are classic drift migrants’ and I remember, too, some discussion between him and the other senior observers concerning the (then still unusual) cross-Baltic movements to Sweden in spring. Not for a moment, however, did they consider that the species would one day breed in Britain. In 1992, when the Common Rosefinch, as it is now called, bred successfully at Flamborough Head, East Yorkshire and on the Suffolk coast, its addition to the regular breeding birds of Britain seemed imminent. No such event has ensued. Since the late 1970s, the number of British and Irish records has grown so noticeably in spring that this trend, and particularly the 1992 influx, are likely to be associated with the much-increased breeding population of southern Fenno-Scandia. -

A Study of the House Finch

40 B•.ROTOLO,A Study of the House Finch. [Jan.Auk A STUDY OF THE HOUSE FINCH. BY W. H. BERGTOLD, M.D. Tus characteristic native bird of the cities and towns of Colorado is the HouseFinch (Carpodacus mexicanusfrontalis); notwithstand- ing its sweetand characteristicsong, it is commonlymistaken by the averagecitizen and visitorfor the EnglishSparrow. Previous to the advent of the English Sparrow in Denver (about 1894, accordingto the writer's notes)the only bird at all commonabout the buildingsof Denver was this finch. Before the presentextensive settlement of Colorado,the HouseFinch was, so far as one can gather from the reports of the various early exploringexpeditions, to be found mainly along the tree covered 'bottoms' of the larger streams,along the foot hills, to a small extent up the streamsinto the foot hills, and possiblyalong the streamsas they neared the east line of the state. For the past six years,the writer has systematicallyand par- ticularly studied this species,bearing in mind severalproblems concerningit; the data securedin this work is now publishedfor the first time. It seemsdesirable to sayhere that the writer aloneis responsible for eachand every note, observation,and conclusiongiven in the followingparagraphs, the samehaving been drawn entirely from his personalstudies: everythingherein followingis published without prejudiceto past observationsand conclusions. METHOD OF STUDY. Under this captionare includedthe usualgeneral observation of the bird wheneverseen in andabout the city, andspecial arrange- mentsat the officeand homeof the writer, designedto facilitate minuteobservations, and to })ringabout a moreintimate acquain- tance with the bird. The officeis on thesixth floor of a buildingsituated in the heart of the businessdistrict of Denver, and providedwith suitable foodand drinkingtrays on the windowsill.