I October 2014 TABLE of CONTENTS COMMISSION DECISIONS 10-07

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Houston Baseball Notes 16 CONFERENCE TITLES • 22 NCAA REGIONALS • 4 NCAA SUPER REGIONALS • 2 COLLEGE WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE & RESULTS GAMES 1-3 • HOUSTON Vs

HOUSTOn baseball notes 16 CONFERENCE TITLES • 22 NCAA REGIONALS • 4 NCAA SUPER REGIONALS • 2 COLLEGE WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE & RESULTS GAMES 1-3 • HOUSTON vs. TEXAS SOUTHERN • FEB. 20-21, 2021 FEBRUARY (0-0) 20 TEXAS SOUTHERN (DH) 11 a.m. 20 TEXAS SOUTHERN 45 minutes after 21 TEXAS SOUTHERN 2 p.m. 23 A&M-CORPUS CHRISTI 3 p.m. 26 # at A&M-Corpus Christi 6 p.m. 27 # at A&M-Corpus Christi 6 p.m. 28 # at A&M-Corpus Christi 1 p.m. MARCH (0-0) 3 at Lamar 6 p.m. HOUSTON COUGARS TEXAS SOUTHERN TIGERS 5 TEXAS 6:30 p.m. RECORD _______________________________0-0 6 TEXAS 2 p.m. RECORD _______________________________0-0 7 TEXAS Noon RANKING (Collegiate Baseball) _________________ 48 RANKING ______________________________ NR 10 at Incarnate Word 6:30 p.m. HEAD COACH ____________ Todd Whitting (Houston, ‘95) HEAD COACH ____ Michael Robertson (Huston-Tillotson, ‘87) 12 at Texas State 6 p.m. CAREER RECORD ____________ 325-229-1 (11th season) CAREER RECORD _____________ 442-494 (19th season) 13 at Texas State 2:30 p.m. RECORD at HOUSTON _____________________ Same RECORD at TEXAS SOUTHERN _____271-324 (13th season) 14 at Texas State 1 p.m. 16 TEXAS A&M 6:30 p.m. PROBABLE STARTERS (2020 STATISTICS) 19 at Oklahoma 6:30 p.m. 20 at Oklahoma 2 p.m. SATURDAY GAME 1 — LHP Robert Gasser (0-0, 11.05 ERA) vs. RHP Kam Fields (0-0, 5.40 ERA)^ 21 at Oklahoma 12:30 p.m. SATURDAY GAME 2 — RHP Ben Sears (1-0, 3.18 ERA)^ vs. -

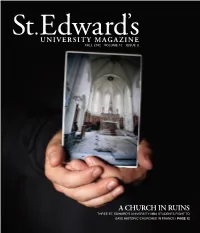

St. Edward's University Magazine Fall 2012 Issue

’’ StSt..EdwardEdwardUNIVERSITYUNIVERSITY MAGAZINEMAGAZINEss SUMMERFALL 20201121 VOLUME 112 ISSUEISSUE 23 A CHurcH IN RUINS THree ST. EDWarD’S UNIVERSITY MBA STUDENts FIGHT TO save HISTORIC CHurCHes IN FraNCE | PAGE 12 79951 St Eds.indd 1 9/13/12 12:02 PM 12 FOR WHOM 18 MESSAGE IN 20 SEE HOW THEY RUN THE BELLS TOLL A BOTTLE Fueled by individual hopes and dreams Some 1,700 historic French churches Four MBA students are helping a fourth- plus a sense of service, four alumni are in danger of being torn down. Three generation French winemaker bring her share why they set out on the rocky MBA students have joined the fight to family’s label to Texas. road of campaigning for political office. save them. L etter FROM THE EDitor The Catholic church I attend has been under construction for most of the The questions this debate stirs are many, and the passion it ignites summer. There’s going to be new tile, new pews, an elevator, a few new is fierce. And in the middle of it all are three St. Edward’s University MBA stained-glass windows and a bunch of other stuff that all costs a lot of students who spent a good part of the summer working on a business plan to money. This church is 30 years old, and it’s the third or fourth church the save these churches, among others. As they developed their plan, they had parish has had in its 200-year history. to think about all the people who would be impacted and take into account Contrast my present church with the Cathedral of the Assumption in culture, history, politics, emotions and the proverbial “right thing to do.” the tiny German village of Wolframs-Eschenbach. -

21St SCS Competes in 2008 Guardian Challenge

COMMANDER’S CORNER: WINNERS ANNOUNCED AT AFSPC BANQUET - PAGE 3 Peterson Air Force Base, Colorado Thursday, May 1, 2008 Vol. 52 No. 18 21st SCS competes in 2008 Guardian Challenge By Senior Airman Stephen Collier base could lose a signifi cant portion of its ability 21st Space Wing Public Affairs to communicate. Th e 21st Space Communications Squadron’s “Th e tech control facility is the heart of the two-man team tried to prove they’re the (space communications) squadron with the “best of the best” April 22 during the 2008 limbs coming from our sister fl ights,” he said. Guardian Challenge communications squad- His counterpart, Airman Needham, wasn’t ron competition. as thrilled in the beginning. Competing in the Air Force Space Command- “It was stressful (for me). I was nervous wide event, Senior Airmen Jack Needham and as heck,” Airman Needham said. “And once Jeremiah Toney, both technical controllers in Colonel (Jay) Raymond visited, my stomach the 21st SCS, were competing against rival com- dropped. But once the competition started, the munications squadrons to show who was better nervousness went away. Th at’s when we went at supporting a space-based mission. into the ‘get-it-done’ mode.” “Th e competition was good; it’s what we Col. Jay Raymond, 21st Space Wing com- expected,” Airman Toney said. “Th ere was mander, and Chief Master Sgt. Timothy Omdal, a moderate amount of fun. Overall, it was the wing’s command chief, visited the Guardian enjoyable.” Challenge competitors to help bolster their mo- Th e competition challenged the Airmen in sev- rale beforehand. -

The Faces of the Humanities

SPRING 2004 VOLUME 5 ISSUE 3 the faces of the humanities TEXAS ACADEMY OF SCIENCE WINNERS BLACK HERITAGE MONTH FACULTY RESOURCE CENTER BRINGING AMADEUS TO THE STAGE JASON JONES c a m p u s SNAPSHOT IN THIS ISSUE St. THE FACES OF THE HUMANITIES Edward’sUNIVERSITY MAGAZINE ISSUE EDITOR CAMPUS BEAT Stacia Hernstrom 2 President’s Agenda, Dell Exec on Campus, ART DIRECTOR Texas Academy of Science Winners, Ben Chomiak Faculty Authors EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Carrie Johnson FEATURES ALUMNI NOTES EDITOR 8 Future Forward Michelle Martinez, ’01 page 12 Keeping St. Edward’s “in the black” PHOTO EDITOR & DESIGNER 9 Philanthropy Lori Najvar How two foundations are helping adult CLASSES ON THE EDGE DESIGNER students attend SEU E. Brook Haley 10 Hilltop Voices INTERNS Mariscela Mendez, ’05 11 Inner Workings Alicia Tuben, ’04 The Faculty Resource Center: Training professors to use technology in the classroom ST. EDWARD’S UNIVERSITY PRESIDENT SPECIAL SECTION George E. Martin, PhD 12 The Faces of the Humanities VICE PRESIDENT OF UNIVERSITY ADVANCEMENT 14 The Artists Michael F. Larkin 16 The Communicators page 34 VICE PRESIDENT OF MARKETING Paige Booth 18 The Designers LOOK FOR THE MOUSE DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS 20 The Linguists Stephanie Elsea When you see this symbol, visit 22 The Musicians “The Faces of the Humanities” St. Edward’s University Magazine online gallery — and access 24 The Philosophers photos, paintings, essays, short is published three times a year by the stories, poems, performances St. Edward’s University Marketing Office for 26 The Photographers and songs from the humanities superstars featured in this issue. -

Managers Tun, to Indie Promotion

ICD 08120 LO9O6 t13 1-1Dti30 ONO-1 z W13 01Lf tt d ti A 3 l 0 1 !' 0 A1N3389 A1NDW 4'a adW ß2?Z09t099010 slv * ** YY i r 1986/$3.50 (U.S.) VOLUME 98 NO. 21 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT May 24, CDs Are A Growth Business LEVY ON AUDIO HARDWARE ONLY? For In -Store Thieves, T00 Senate Bill May Drop Tape Royalty Plan tion's higher cost, but also to tight provision to place a royalty fee on en -month -old bill, S. 1739, intro- BY GEOFF MAYFIELD supply. "When you've got a demand BY BILL HOLLAND blank tape when it takes the bill to duced by subcommittee chairman NEW YORK The compact disk is product that people can fence for WASHINGTON In a dramatic con- markup Wednesday (21). This could Charles McC. Mathias (R -Md.), may becoming the darling of profession- more than a record or tape -they cession to consumer electronics in- chop the anticipated $200 million an- find the necessary votes to send it al and amateur thieves. can get as much as $6 or $8 apiece dustry opponents of the audio-only nual royalty pool by more than half. to the full Judiciary Committee, At least two major chains and for CDs -the value of the product home taping bill, the Senate Copy- Sources say that with the hotly with only the hardware royalty fea- several regional webs report that (Continued on page 89) right Subcommittee may drop the contested provision deleted, the sev- ture intact. -

Rečnik Novijih Anglicizama

VERA VASIĆ • TVRTKO PRĆIĆ • GORDANA NEJGEBAUER DU YU SPEAK ANGLOSRPSKI? REČNIK NOVIJIH ANGLICIZAMA Treće, elektronsko, izdanje 950 ODREDNICA SA ● pravopisom, izgovorom ● definicijom i gramatikom ● srpskim ekvivalentom izvornim engleskim ● ● indeksom integrisanosti oblikom Du yu speak anglosrpski? Rečnik novijih anglicizama, treće, elektronsko, izdanje Vera Vasić Tvrtko Prćić Gordana Nejgebauer DU YU SPEAK ANGLOSRPSKI? REČNIK NOVIJIH ANGLICIZAMA Treće, elektronsko, izdanje objavljeno i dostupno u Digitalnoj biblioteci Filozofskog fakulteta Du yu speak anglosrpski? Rečnik novijih anglicizama, treće, elektronsko, izdanje Du yu speak anglosrpski? Rečnik novijih anglicizama, treće, elektronsko, izdanje, objavljeno i dostupno u Digitalnoj biblioteci Filozofskog fakulteta, predstavlja digitalnu verziju štampane knjige Du yu speak anglosrpski? Rečnik novijih anglicizama (Zmaj, Novi Sad, 2001). Saglasnost za objavljivanje rečnika dalo je Nastavno-naučno veće Filozofskog fakulteta, na sednici održanoj 2. februara 2018. godine. NAPOMENA O AUTORSKOM PRAVU: Nijedan deo ove publikacije ne može se preštampati, reprodukovati ili upotrebiti u bilo kom obliku bez pisanog odobrenja autorâ, kao nosilaca autorskog prava. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced or utilized in any form without permission in writing from the authors, as the holders of the copyright. objavljeno i dostupno u Digitalnoj biblioteci Filozofskog fakulteta Du yu speak anglosrpski? Rečnik novijih anglicizama, treće, elektronsko, izdanje RUBRIKA SKRAÃENICE I SIMBOLI U VODIÅU A, B, … posebne odrednice s istim pisanim oblikom det determinativ det (1, 2, …) determinativ vezan za znaåenje pod datim brojem Dsg. dativ singulara (jednine) (Á) oblik ili znaåenje ne postoji u engleskom eng. engleski impf imperfektivni (nesvršeni) glagol indekl indeklinabilna (nepromenljiva) imenica intr intranzitivni (neprelazni) glagol i sl. i sliåne reåi u datom opsegu znaåenja m muški rod neform. -

Annual Operating Budget 2011-2012 History of Round Rock

Annual Operating Budget 2011-2012 History of Round Rock ...Our Story Settlers began arriving in the area in the late 1830s and built Kenney Fort on the south side of Brushy Creek. In 1850, the original town, called Brushy, was established on the north side of the creek near the “round rock.” This historic table-shaped rock still marks a Brushy Creek crossing of the famed Chisholm Trail. In 1854, Brushy was renamed Round Rock. The town served as a stop on the Chisholm Trail through- out the 1860s and the early 1870s. In 1876, the residents moved the town about one mile due east to take advantage of the newly constructed International and Great Northern Railroad line (later know as the Missouri Pacific) which bypassed the old town. Round Rock was officially incorporated in 1913. Today, the Old Town section still contains many historic structures and is the centerpiece of an evolving, his- torical, recreational and commercial area. www.roundrocktexas.gov City of Round Rock Annual Budget For the Fiscal Year OCTOBER 1, 2011 • SEPTEMBER 30, 2012 CITY LEADERSHIP: ALAN McGRAW Mayor CARLOS T. SALINAS Mayor Pro-Tem- Place 4 CRAIG MORGAN Council Member - Place 1 GEORGE WHITE Council Member - Place 2 JOE CLIFFORD Council Member - Place 3 JOHN MOMAN Council Member - Place 5 KRIS WHITFIELD Council Member - Place 6 STEVE NORWOOD City Manager LAURIE HADLEY Assistant City Manager BRYAN WILLIAMS Assistant City Manager Published in accordance with the City of Round Rock Home Rule Charter www.roundrocktexas.gov i Budget Presentation Award The Government Finance Officers Association of the United States and Canada (GFOA) presented a Distinguished Budget Presentation Award to City of Round Rock, Texas for its annual budget for the fiscal year beginning October 1, 2010. -

Dražen Vrdoljak – Čovjek Koji Je Utemeljio I Formatirao Rock Kritiku

Dražen Vrdoljak – Čovjek koji je utemeljio i formatirao rock kritiku Dražen Vrdoljak rođen je 1. travnja 1951. u Splitu gdje završava gimnaziju, a 1969. dolazi u Zagreb na studij ekonomije. Od 1970. djeluje kao glazbeni novinar i kritičar, najprije u omladinskom, ubrzo u dnevnom tisku (Slobodna Dalmacija, Vjesnik, Večernji list) te tjednim listovima (Nedjeljna Dalmacija, Telegram, Oko, VUS, Studio). U njima prati pop, rock, jazz i zabavnu glazbu kritičkim diskursom koji često protuslovi tadašnjem samoproklamiranom sustavu vrijednosti na domaćoj glazbenoj sceni. Vrdoljakov medijski rad istodobno se širi na radio i televiziju (RTV Zagreb, 1971) gdje se u tisućama emisija, kao i u tisku, zalaže za jednake kriterije u procjenjivanju domaće i svjetske glazbene produkcije. Iako mu često prigovaraju da favorizira inozemnu glazbu, o njoj nikad ne prestaje informirati, među ostalim i prijevodima Ilustrirane rock enciklopedije (1978) i Ilustrirane jazz enciklopedije (1980). Blisko povezan s fenomenima koji su 70-ih mijenjali sliku popularne glazbe bivše države i projektima izvan dnevnog novinarstva (produkcija prvog albuma Buldožera 1975 te 1981. s Darkom Glavanom knjiga o Bijelom dugmetu pod naslovom Ništa mudro), Dražen Vrdoljak sudjeluje u organizaciji glazbenih manifestacija (Muzički biennale, festival Jazz Fair, YURM, programi Univerzijade ‘87, Eurosong ‘90, Croatian Music Aid), klupskih programa u vrijeme uzleta novoga vala (GSC Kulušić i Lapidarij) i mnogih koncerata (uključujući Rolling Stonese 1998. u Zagrebu). Bio je suradnik Leksikografskog -

2008-Texas Traffic Safety Annual Report

TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Texas Traffic Safety 2008 Annual Report Texas Traffic Safety Annual Report – FY 2007 This Page Intentionally Left Blank 222 000 000 TEXAS TRAFFIC SAFETY 888 ANNUAL REPORT TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 125 E. 11TH STREET AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 http://www.txdot.gov Texas Traffic Safety Annual Report – FY 2008 Governor Rick Perry Amadeo Saenz P.E. Governor’s Highway Safety Representative Executive Director Texas Department of Transportation Carlos A. Lopez, P.E. Director, Traffic Operations Division Texas Department of Transportation Terry A. Pence Traffic Safety Director Texas Department of Transportation 125 E. 11th Street Austin, Texas 512-416-3175 Page ii Texas Traffic Safety Annual Report – FY 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................................................5 TRAFFIC SAFETY PROGRAM ..............................................................................................................................................7 CRASH SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................................................7 CHALLENGES ....................................................................................................................................................................8 MISSION ............................................................................................................................................................................9 -

8-16-16 Transcript Bulletin

FRONT PAGE A1 Citizens of Rush Valley celebrate their town together See A10 TOOELETRANSCRIPT SERVING TOOELE COUNTY BULLETIN SINCE 1894 TUESDAY August 16, 2016 www.TooeleOnline.com Vol. 123 No. 22 $1.00 Grass fire causes evacuation, torches 10 acres STEVE HOWE quickly spread the fire through STAFF WRITER the dry, yellow grass beyond More than 10 acres of a England Acres Park. field were damaged by a grass Whitehouse said the fire fire that was sparked Monday switched direction four times morning by a pair of young as the wind changed, leaving boys, according to the Tooele a twisting swath of blackened City Fire Department. ground as the fire threatened The fire began near the homes on the east and west of intersection of 1000 North and the field, which is Tooele City 400 East and was reported property. The fire also reached at 10:13 a.m., Tooele City the top of a Tooele City water Fire Chief Bucky Whitehouse said. Strong, swirling winds SEE FIRE PAGE A9 ➤ DAVID BERN/TTB PHOTO A large grass fire erupted Monday morning next to England Acres Park in Tooele City, forcing evacuations of nearby homes and burning an estimated 10 acres before fire crews doused the blaze. The fire was reportedly started by two young boys playing with a lighter. A Tooele City firefighter (above) mops up while city park workers (left) watch fire crews to make sure the flames are extinguished. July 19 fire debris buried at landfill TIM GILLIE STAFF WRITER Two hundred and forty tons of debris from the July 19 fire that devastated a west side Tooele City neighborhood has been buried at the Tooele County Landfill in Bauer. -

August 8-14, 2013 ------Cover Story • Janice Furtner

AUGUST 8-14, 2013 --------------------------- Cover Story • Janice Furtner -------------------------- Saturday, August 17 • 8:00pm ADJOA SKINNER $8 Adv., $10 D.O.S., $15 Gold An Artist Soldiers On By Heather Miller began cutting paper, a limited budget forced her to be inventive. Furtner Janice Furtner has a voice that is covered ordinary typing paper with best absorbed with one’s eyes closed. black, liquid ink and let the soaked pa- Its smooth, melodic tone can transport pers dry, sometimes crispy and curled a listener’s mind outside of this terres- at the edges. She used the dark pieces trial world to a place where art perme- of paper to cut small designs. Most of ates and massages the soul. Her voice her early pieces were smaller than four lifts the window and invites visitors to inches. slip inside to a place where art, music Paper cutting was an obsession and the written word reign supreme. In that she connected to deeply. Cutting Furtner’s world the arts are held high, and exploring, she used the simple and thoughts of money, traffic, trips tools of scissors and paper to investi- to the store and daily hassles are left gate music, emotions and her connec- Saturday, August 24 • 8:00pm to slip into secondary position, right tion to nature. where they belong. Her vocal training took her to As a trained musician with a de- places like Vienna, where Furtner was NICK MOSS gree in vocal performance, Furtner immersed in music, singing and art. $20 Adv., $25 D.O.S., $35 Gold sings soprano with the Heartland Inspiration poured down on her from Chamber Choir, a group she has been paintings and art pieces created by Wednesday, Sept. -

ASHRAE Newsletter

1 August 2017 AUSTIN, TEXAS CHAPTER est. 1956 ashrae.org ausnashrae.weebly.com FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESK Inside this issue: Welcome back to Austin ASHRAE! It is my pleasure to serve as your local chapter president this year! Before we get started, I wish Programs 2 to thank David Driggers for his leadership and guidance in the past year. As was his stated goal last September, he has left our chapter in PrePay Option 5 a BETTER position than when he took office, and I plan to continue that trend with your help and involvement. Baseball Event 6 Steve Hansen For those that don't know me, I have been in the industry for 20 Treasurer’s Report 7 Chapter President years: first in Houston at a consulting engineering firm, then Dallas as a design-build mechanical subcontractor, and the last 7+ years in Austin at a large general contractor. My goals for the upcoming year BOG Meeting Minutes 8 in ASHRAE are to 1)increase member attendance at chapter meetings by at least 15% through consistent communication and excellent, principal-level programs that dig deep into Officer Roster 12 relevant topics and 2)increase research promotion by aligning the RP events with the member's interests. Unpaid Society Dues 13 I would like to personally thank the excellent team of volunteers who are working hard for History 15 the members this year. I feel like I'm managing an all-star team. We still have one spot to fill: Student Activities chair. Gayle Davis has done an excellent job the last few years, and has stepped up to be our Chapter Vice President this year.