Caledonian Muse Essay Edited For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radiohead's Pre-Release Strategy for in Rainbows

Making Money by Giving It for Free: Radiohead’s Pre-Release Strategy for In Rainbows Faculty Research Working Paper Series Marc Bourreau Telecom ParisTech and CREST Pinar Dogan Harvard Kennedy School Sounman Hong Yonsei University July 2014 RWP14-032 Visit the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series at: http://web.hks.harvard.edu/publications The views expressed in the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. Faculty Research Working Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. www.hks.harvard.edu Makingmoneybygivingitforfree: Radiohead’s pre-release strategy for In Rainbows∗ Marc Bourreau†,Pınar Dogan˘ ‡, and Sounman Hong§ June 2014 Abstract In 2007 a prominent British alternative-rock band, Radiohead, pre-released its album In Rainbows online, and asked their fans to "pick-their-own-price" (PYOP) for the digital down- load. The offer was available for three months, after which the band released and commercialized the album, both digitally and in CD. In this paper, we use weekly music sales data in the US between 2004-2012 to examine the effect of Radiohead’s unorthodox strategy on the band’s al- bum sales. We find that Radiohead’s PYOP offer had no effect on the subsequent CD sales. Interestingly, it yielded higher digital album sales compared to a traditional release. -

Q1 2016 PFS Newsletter.Pdf

PFS — "Checking In Newsletter" —April 2016 View this email in your browser arrive. relax. go out. Location Spotlight Events Music premier location spotlight Jersey City, NJ The Pier Property Profile 1 Harborside Place Jersey City, NJ 07302 THE BUILDING This modern low-rise waterfront building is centrally located by restaurants, shopping, public transportation, and the financial center of Jersey City. The Pier provides an array of amenities such as a 24-hour fitness center, concierge and dry cleaning service, club-room and an amazing rooftop deck with panoramic views of New York City. THE NEIGHBORHOOD Jersey City is the second-largest city in New Jersey. The growing popularity of New York City in the 1990s had a significant impact on Jersey City. The waterfront area has become become the site of gleaming new office towers and luxury condominiums. Jersey City now houses the back office functions of many New York City-based companies, earning it the moniker "Wall Street West." Jersey City is served by the PATH train. It offers a convenient and fast commute to Manhattan- taking approximately 15 minutes from most Jersey City locations. Go Back To Top events Tribeca Film Festival Spring, as one of my favorite times of the year; with the blooming of the flowers and the sounds of the sneezing allergenic NY commuter, is the Tribeca Film Festival. Two weeks of events highlighting one of the most popular pastimes, movie going, brings a normal Joe like me, to the world of artistic people. Easily one of the most convenient areas of NYC to explore, take advantage of an event like this and catch a movie or two. -

C Rossing the P on D

8 [ URBANITE Thursday J December i l * 2003 Crossing the Pond American bands make it overseas but don’t leave a dent in their home country LEILA REGAN___________ “U.K. taste is a lot more Both Associate Urbanite Editor diverse,” says long-time Hiss Bluett and l regan @gsusignal. com promoter and friend and Atlanta Harren appre- Handpicked by quintuple hipster DJ, Dennis Millay, ciated the platinum selling Brit-pop heroes “They care a lot more about “bonus” of Oasis. Exalted by England’s their music. Music is so dispos- having one of most popular music magazine, able here.” the most the National Music Express Swaminathan echoes these influential (NME). Produced by renowned sentiments. men in Brit-pop producer Owen “The U.K. celebrates all England rav- Morris. Seen by thousands at sorts of music,” he said. A ing about the popular English music festivals British citizen’s collection band they in cities such as Leeds and could include the Strokes, represented. Redding. Signed to major Radiohead and Britney Spears. Skipping all British label Polydor’s new sub Here, a Strokes fan would not the grief of sidiary, Loog, which is operated listen to Britney Spears. Brits dealing with by Andrew Loog Oldham (the are a lot more accepting.” middlemen Rolling Stones' original manag “The U.K. is notoriously certainly er and producer). more open to different sounds helped the In spite of all the attention and styles of music,” said 99X Hiss to in the UK, the Hiss still remains music director and ex-manager achieve suc- Special I Signal as they always have been: a of the Hiss, Jay Harren. -

Muse-2020-SINGLES1-1.Pdf

TWENTY TWENTY Self Portrait Heidi Hughes contents Poetry clarity Jillian Oliver ................................................................... 2 I Know You Rayleigh Caldwell .................................................. 2 strawberry Bailey Stuart ........................................................... 3 The Girl Behind the Mirror Erin Gonzalez .............................. 4 exile from neverland Jillian Oliver ........................................... 7 I Once… Erin Gonzalez .............................................................. 7 if ever there should come a time Jillian Oliver ........................ 8 Hello Friend Julia Shelton The Trend Fernanda Carbajal Rodriguez .................................. 9 Love Sonnet Number 666 ½ Jake C. Woodlee .........................11 the end of romance Jillian Oliver ............................................11 What Kindergarten Taught Me Morgan Bryson ..................... 43 Facing Fear Melissa Brown ....................................................... 44 Sharing the Love with Calhoun’s Community ........................... 44 ESSAY Dr. Leigh Ann Rhea J.K. Rowling: The Modern Hero Melissa Brown ................... 12 In the Spotlight: Tatayana Rice Jillian Oliver ......................... 45 Corn Flakes Lance Voorhees .................................................... 15 Student Success Symposium Jillian Oliver .............................. 46 Heroism in The Outcasts of Poker Flat Molly Snoddy .......... 15 In the Spotlight: Chad Kelsoe Amelia Chey Slaton ............... -

The Strokes Share New Episode of Pirate Radio Series Featuring Colin Jost and Gordon Raphael

THE STROKES SHARE NEW EPISODE OF PIRATE RADIO SERIES FEATURING COLIN JOST AND GORDON RAPHAEL “BAD DECISIONS” CLIMBING TOP 10 AT ALT RADIO FIRST ALBUM IN SEVEN YEARS THE NEW ABNORMAL OUT NOW VIA CULT/RCA RECORDS TO CRITICAL ACCLAIM July 23, 2020—Today, The Strokes share a new installment of their ongoing pirate radio series, “Five Guys Talking About Things They Know Nothing About”—watch it HERE. The new episode is the third installment of the show, and the first in a series in which the band will speak with the producers of their albums. The episode airing today features The Strokes in conversation with Gordon Raphael—who produced their debut EP The Modern Age, their first two LPs Is This It and Room On Fire and contributed to their third LP First Impressions Of Earth—as well as their longtime friend, SNL’s Colin Jost. The band’s new album The New Abnormal, their first in seven years, was released in April to widespread critical acclaim. The album’s lead single, “Bad Decisions,” is currently Top 10 at Alternative radio and still climbing, marking the band’s first Alternative Top 10 since 2006 and setting the record for the most time between Alternative Top 10 entries. Additionally, “Bad Decisions,” went #1 on AAA in April. Upon release, The New Abnormal debuted at #1 on Billboard’s Top Album Sales Chart and reached #8 on the Billboard 200, #1 Current Rock Album, #1 Top Current Album, #1 Current Alternative Album and #1 Vinyl Album. Of The New Abnormal, The Times of London praises “The Strokes give us their second masterpiece,” while The -

Uk Versus Usa at the Shockwaves Nme Awards 2007

STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 8PM MONDAY 29 TH JANUARY Insert logo UK VERSUS USA AT THE SHOCKWAVES NME AWARDS 2007 Expect blood, sweat and tears as we prepare for what will undoubtedly be one big dirty rock’n’roll battle of the bands – and of the nations – at the Shockwaves NME Awards 2007 . The best of British – Arctic Monkeys , Muse and Kasabian – will take on stateside success stories My Chemical Romance and The Killers on March 1 at Hammersmith Palais. Let battle commence! This year, there’s no one clear leader but FIVE bands that dominate the nominations list. With four nominations each, Arctic Monkeys, Muse, Kasabian, The Killers and My Chemical Romance have been chosen by the fans to fight it out on the night. For the past two years, it’s been British bands sweeping the board, but this year The Killers and My Chemical Romance may very well make the 2007 ceremony a stateside success story. Arctic Monkeys made NME Awards history last year by scooping the Award for both Best New Band and Best British Band in the same year, in addition to winning Best Track and scoring a nomination for Best Live Band . Sheffield’s favourites have matched their achievement, with four nominations this year for Best British Band, Best Live Band, Best Album and Best Music DVD. Arctic Monkeys said: “Very nice, we didn’t think we would get any this year! It seems weird for us to be alongside them [the competition] because we still feel like a little band. When it’s your own thing you don’t really see yourself alongside The Killers and Kasabian.” The Monkeys have more than one tough fight on their hands if they want to claim the Best British Band title for the second year running, though. -

Musique the Strokes 05 Radiohead 06 the Kills 10

MUSIQUE THE STROKES 05 RADIOHEAD 06 THE KILLS 10 THE VACCINES 12 RAPHAEL SAADIQ 13 UP METRONOMY 14 LE PRINCE MIIAOU 15 DVD MONSTERS 22 MEAN STREETS 24 A BOUT START NUMÉRO 161 PORTANT 25 UN BALCON SUR LA MER 26 BAMBI 28 AVRIL 2011 L’ACTUALITÉ MUSIQUE ET VIDÉO DE VOTRE SPÉCIALISTE CULTURE RED 30 INTERVIEW DE JOHN MALKOVICH 30 SUM41 UNE PUBLICATION SOMMAIRE 12 10 13 14 18 News /05 The Strokes 05/Radiohead 06/ Alela Diane 06/Jehro 07/Noah and the Whale 07/ Interviews /08 SUM 41 08/The Kills 10/The Vaccines 12/ Raphael Saadiq 13/Metronomy 14/Le Prince Miiaou 15/ Chroniques musique /16 Pop/Rock 16/Français 18/Autres musiques 20/Electro 21/Rap-Soul 21/ Chroniques DVD /22 DVD du mois : Monsters 22/Mean Streets 24/Taking Off 24/ La Meute 25/A Bout Portant 25/Un Balcon sur la mer 26/ South Park 26/Bambi 28/Raiponce 28/Megamind 28/ RED 30/Interview de John Malkovich 31/ UP START est édité par la société PRÉLUDE ET FUGUE, SAS de presse au capital de 30 000 euros, 29, rue de Châteaudun 75308 PARIS Cedex 09 Tél. : 01 75 55 43 44 Fax : 01 75 55 41 11 DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION Rick DE NOLF/ PRINCIPAL ACTIONNAIRE GROUPE EXPRESS-ROULARTA RÉDACTION RÉDACTRICE EN CHEF Florence RAJON/[email protected]/ RÉDACTION Paul Alexandre, David Bouseul, François Cano, Hervé Crespi, Laurent Denner, Hervé Guilleminot, Maxime Goguet, Bertrand Rocher/ CONCEPTION GRAPHIQUE Didier FITAN MANAGEMENT ÉDITEUR DÉLÉGUÉ Tristan THOMAS/ DIRECTRICE RÉGIE Valérie SALOMON/ PUBLICITÉ Tristan THOMAS [email protected]/ FABRICATION Pascal DELEPINE avec Laurence BIDEAU/ PRÉPRESSE GROUPE EXPRESS-ROULARTA/ IMPRIMÉ EN BELGIQUE Roularta Printing/Couverture D.R. -

If Censorship in the 'Axis of Evil'

IF CENSORSHIP IN THE ‘AXIS OF EVIL’ IS EVIL IS CENSORSHIP IN THE ‘AXIS OF GOOD’ THEN GOOD? -Questions and answers on music censorship in the US...and the rest of the world FEATURING REEBEE GAROFALO & MARK LEVINE WHY IS MUSIC CENSORED? Censorship of music has existed ever since ancient Greece. Plato distinguished between “good” and “bad music” – suggesting that the “bad” had to be controlled or banned as it had the potential to divert people from the “good life”. Today music censorship is more complex. Active censors of music are states, religions, educational systems, families, retailers and lobbying groups. Censorship can be extreme, musicians being silenced, like the killings of musicians in Algeria, and the total ban on music in Afghanistan under the Taliban. Or it can be apparently banal, like the banning of certain songs during times of war and terrorism. Threats can lead to self-censorship and thus deprive musicians of their right to free expression. Music is a free expression of the ideas, traditions and emotions of individuals and of peoples. These expressions may confl ict with the politics of those in power. It may be as simple as South African musician Johnny Clegg said: “censorship is based on fear.” WHAT IS FREEMUSE? FREEMUSE - THE WORLD FORUM ON MUSIC AND CENSORSHIP is an independent international membership organization advocating freedom of expression for musicians and composers world- wide. As our guide are the principles outlined in the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights as they apply specifi cally to musicians and composers. The FREEMUSE secretariat was established in August 2000. -

Time Limit at the Minimum Velocity Corresponding to Characterisation

Time limit at the minimum velocity corresponding to V & O 2 max : characterisation and determinant factors A study conducted in swimmers with different competitive levels and gender Tese apresentada às provas de Doutoramento no ramo das Ciências do Desporto, nos termos do Decreto-Lei n.º 216/92, de 13 de Outubro, orientada pelo Professor Doutor João Paulo Vilas-Boas Presentation of Doctoral Thesis in Sport Sciences according to the Decree-Law nº 216/92, of 13 of October, under the supervision of Professor Doutor João Paulo Vilas-Boas Ricardo Jorge Pinto Fernandes Porto, 2006 Fernandes, Ricardo J. P. (2006). Time limit at the minimum velocity corresponding to V& O2max characterisation and determinant factors. A study conducted in swimmers with different competitive levels and gender. Doctoral Thesis in Sport Sciences according to the Decree-Law nº 216/92, of 13 of October. University of Porto, Faculty of Sport. KEY WORDS: SWIMMING, TIME LIMIT, ENERGY COST, OXYGEN CONSUMPTION, LACTATE CONCENTRATIONS, STROKING PARAMETERS PALAVRAS CHAVE: NATAÇÃO, TEMPO LIMITE, CUSTO ENERGÉTICO, CONSUMO DE OXIGÉNIO, LACTATEMIA, PARÂMETROS BIOMECÂNICOS GERAIS Acknowledgments At this point, I would like to take the opportunity to express my gratitude to all that have supported me on the process of elaboration of this Doctoral Thesis. First, I would like to deeply acknowledge the University of Porto, in particular to the Faculty of Sport, for enabling me to get a PhD and to give me all the facilities and means to proceed with all the implicit tasks of a work of this nature. In particular, I have to thank Prof. Dr. -

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay

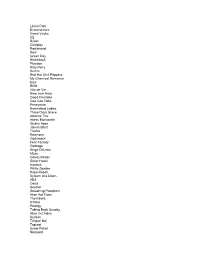

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay Radiohead Korn Green Day Nickelback Placebo Katy Perry Kumm Red Hot Chili Peppers My Chemical Romance Eels REM Vita de Vie Nine Inch Nails Good Charlotte Goo Goo Dolls Pennywise Barenaked Ladies Three Days Grace Alkaline Trio Alanis Morissette Guano Apes James Blunt Travka Reamonn Godsmack Fear Factory Garbage Kings Of Leon Muse Gandul Matei Sister Hazel Incubus White Zombie Papa Roach System of a Down AB4 Oasis Seether Smashing Pumpkins Alien Ant Farm The Killers Ill Nino Prodigy Taking Back Sunday Alice in Chains Kutless Timpuri Noi Taproot Snow Patrol Nonpoint Dashboard Confessional The Cure The Cranberries Stereophonics Blink 182 Phish Blur Rage Against the Machine Gorillaz Pulp Bowling For Soup Citizen Cope Manic Street Preachers Luna Amara Nirvana The Verve Breaking Benjamin Chevelle Modest Mouse Jeff Buckley Beck Arctic Monkeys Bloodhound Gang Sevendust Coma Lostprophets Keane Blue October 30 Seconds to Mars Suede Collective Soul Kill Hannah Foo Fighters The Cult Feeder Veruca Salt Skunk Anansie 3 Doors Down Deftones Sugar Ray Counting Crows Mushroomhead Electric Six Filter Lynyrd Skynyrd Biffy Clyro Death Cab For Cutie Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds The White Stripes James Morrison Texas Crazy Town Mudvayne Placebo Crash Test Dummies Poets Of The Fall Jason Mraz Linkin Park Sum 41 Grimus Guster A Perfect Circle Tool The Strokes Flyleaf Chris Cornell Smile Empty Soul Audioslave Nirvana Gogol Bordello Bloc Party Thousand Foot Krutch Brand New Razorlight Puddle Of Mudd Sonic Youth -

BRYAN HANSEN Song List.Xlsx

BRYAN HANSEN WILLIAM BLAKEY SONG LIST JAN 2018 SONG NAME: ARTIST: LETS STAY TOGETHER AL GREEN DON'T WANNA FIGHT ALABAMA SHAKES I WANT IT THAT WAY BACKSTREET BOYS TWIST AND SHOUT BEATLES COME TOGETHER BEATLES IN MY LIFE BEATLES HEY JUDE BEATLES ACROSS THE UNIVERSE BEATLES SAW HER STANDING THERE BEATLES SOMETHING BEATLES HOLD YOUR HAND BEATLES HIDE YOUR LOVE AWAY BEATLES BLACK BIRD BEATLES ALWAYS A WOMEN BILLY JOEL PIANO MAN BILLY JOEL JUST THE WAY YOU ARE BILLY JOEL FOR THE LONGEST TIME BILLY JOEL YOU MAY BE RIGHT BILLY JOEL BLOWIN IN THE WIND BOB DYLAN DON’T THINK TWICE BOB DYLAN IT AINT ME BABY BOB DYLAN FIRST DAY OF MY LIFE BRIGHT EYES TRUE LOVE WAYS BUDDY HOLLY NOT FADE AWAY BUDDY HOLLY OH BOY BUDDY HOLLY COME DOWN BUSH GLYCERIN BUSH IF YOU WANT TO SING OUT CAT STEVENS FATHER AND SON CAT STEVENS WILD WORLD CAT STEVENS WE DON’T TALK ANYMORE CHARLIE PUTH ONE CALL AWAY CHARLIE PUTH TENESSEE WHISKY CHRIS STAPLETON SKY FULL OF STARS COLDPLAY HYMN FOR THE WEEKEND COLDPLAY SCIENTIST COLDPLAY MR JONES COUNTING CROWS ROUND HERE COUNTING CROWS TWO STEP DAVE MATTHEWS BAND SO MUCH TO SAY DAVE MATTHEWS BAND TOO MUCH DAVE MATTHEWS BAND CRASH INTO ME DAVE MATTHEWS BAND THE STONE DAVE MATTHEWS BAND GREY STREET DAVE MATTHEWS BAND TRIPPING BILLIES DAVE MATTHEWS BAND CRUSH DAVE MATTHEWS BAND FOR YOU DAVID RYAN HARRIS BRYAN HANSEN WILLIAM BLAKEY SONG LIST JAN 2018 HOLD ON WE'RE GOING HOME DRAKE PASSION FRUIT DRAKE HOTLINE BLING DRAKE SAVE TONIGHT EAGLE EYE CHERRY THINKING OUT LOUD ED SHEERAN PERFECT ED SHEERAN PHOTOGRAPH ED SHEERAN ROCKET MAN ELTON JOHN -

Playnetwork Business Mixes

PlayNetwork Business Mixes 50s to Early 60s Marketing Strategy: Period themes, burgers and brews and pizza, bars, happy hour Era: Classic Compatible Music Styles: Fun-Time Oldies, Classic Description: All tempos and styles that had hits Rock, 70s Mix during the heyday of the 50s and into the early 60s, including some country as well Representative Artists: Elvis, Fats Domino, Steve 70s Mix Lawrence, Brenda Lee, Dinah Washington, Frankie Era: 70s Valli and the Four Seasons, Chubby Checker, The Impressions Description: An 8-track flashback of great music Appeal: People who can remember and appreciate from the 70s designed to inspire memories for the major musical moments from this era everyone. Featuring hits and historically significant album cuts from the “Far Out!,” Bob Newhart, Sanford Feel: All tempos and Son era Marketing Strategy: Hamburger/soda fountain– Representative Artists: The Eagles, Elton John, themed cafes, period-themed establishments, bars, Stevie Wonder, Jackson Brown, Gerry Rafferty, pizza establishments and clothing stores Chicago, Doobie Brothers, Brothers Johnson, Alan Parsons Project, Jim Croce, Joni Mitchell, Sugarloaf, Compatible Music Styles: Jukebox classics, Donut Steely Dan, Earth Wind & Fire, Paul Simon, Crosby, House Jukebox, Fun-Time Oldies, Innocent 40s, 50s, Stills, and Nash, Creedence Clearwater Revival, 60s Average White Band, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Electric Light Orchestra, Fleetwood Mac, Guess Who, 60s to Early 70s Billy Joel, Jefferson Starship, Steve Miller Band, Carly Simon, KC & the Sunshine Band, Van Morrison Era: Classic Feel: A warm blanket of familiar music that helped Description: Good-time pop and rock legends from define the analog sound of the 70s—including the the mid-60s through the early-to-mid-70s that marked one-hit wonders and the best known singer- the end of an era.