Spring 2019, Vol. 8, No. 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“I Go for Independence”: Stephen Austin and Two Wars for Texan Independence

“I go for Independence”: Stephen Austin and Two Wars for Texan Independence A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by James Robert Griffin August 2021 ©Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by James Robert Griffin B.S., Kent State University, 2019 M.A., Kent State University, 2021 Approved by Kim M. Gruenwald , Advisor Kevin Adams , Chair, Department of History Mandy Munro-Stasiuk , Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………………...……iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………v INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………..1 CHAPTERS I. Building a Colony: Austin leads the Texans Through the Difficulty of Settling Texas….9 Early Colony……………………………………………………………………………..11 The Fredonian Rebellion…………………………………………………………………19 The Law of April 6, 1830………………………………………………………………..25 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….32 II. Time of Struggle: Austin Negotiates with the Conventions of 1832 and 1833………….35 Civil War of 1832………………………………………………………………………..37 The Convention of 1833…………………………………………………………………47 Austin’s Arrest…………………………………………………………………………...52 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….59 III. Two Wars: Austin Guides the Texans from Rebellion to Independence………………..61 Imprisonment During a Rebellion……………………………………………………….63 War is our Only Resource……………………………………………………………….70 The Second War…………………………………………………………………………78 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….85 -

Spanish, French, Dutch, Andamerican Patriots of Thb West Indies During

Spanish, French, Dutch, andAmerican Patriots of thb West Indies i# During the AMERICAN Revolution PART7 SPANISH BORDERLAND STUDIES By Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough -~ ,~~~.'.i~:~ " :~, ~i " .... - ~ ,~ ~"~" ..... "~,~~'~~'-~ ,%v t-5.._. / © Copyright ,i. "; 2001 ~(1 ~,'~': .i: • by '!!|fi:l~: r!;.~:! Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanca West, Apt B ~.l.-c • Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 !LI.'.. Email: gwhough(~earthiink.net u~ "~: .. ' ?-' ,, i.. Other books in this series include: • ...~ , Svain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. ,. Sp~fin's Califomi0 Patriqts in its 1779-1783 Wor with Englgnd - During the American Revolution, Part 2, :999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in ire |779-1783 War with Engl~n~i - During the Amcricgn RevolutiQn, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Svaln's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-|783 Wit" wi~ England- During the American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's Texa~ patriot~ in its 1779-1783 War with Enaland - Daring the A~a~ri~n Revolution, Fifth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 2000. Spain's Louisi~a Patriots in its; 1779-1783 War witil England - During.the American Revolution, Sixth StUdy of the Spanish Borderlands, 20(~0. ./ / . Svain's Patriots of Northerrt New Svain - From South of the U. S. Border - in its 1779- 1783 War with Engl~nd_ Eighth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, coming soon. ,:.Z ~JI ,. Published by: SHHAK PRESS ~'~"'. ~ ~i~: :~ .~:,: .. Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research ~.,~.,:" P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 (714) 894-8161 ~, ~)it.,I ,. -

Arnoldo HERNANDEZ

Comercio a distancia y circulación regional. ♣ La feria del Saltillo, 1792-1814 Arnoldo Hernández Torres ♦ Para el siglo XVIII, el sistema económico mundial inicia la reorganización de los reinos en torno a la unidad nacional, a la cual se le conoce como mercantilismo en su última etapa. Una de las acciones que lo caracterizó fue la integración del mercado interno o nacional frente al mercado externo o internacional. Estrechamente ligados a la integración de los mercados internos o nacionales, aparecen los mercados regionales y locales, definidos tanto por la división política del territorio para su administración gubernamental como por las condiciones geográficas: el clima y los recursos naturales, entre otros aspectos. El proceso de integración del mercado interno en la Nueva España fue impulsado por las reformas borbónicas desde el último tercio del siglo XVIII hasta la independencia. Para el septentrión novohispano, particularmente la provincia de Coahuila, los cambios se reflejaron en el ámbito político, militar y económico. En el ámbito político los cambios fueron principalmente en la reorganización administrativa del territorio –la creación de la Comandancia de las Provincias Internas y de las Intendencias, así como la anexión de Saltillo y Parras a la provincia de Coahuila. En el ámbito militar se fortaleció el sistema de misiones y presidios a través de la política de poblamiento para consolidar la ocupación – el exterminio de indios “bárbaros” y la creación de nuevos presidios y misiones– y colonización del territorio –establecimiento -

November 3, 2020 General Election Combined Results

NOVEMBER 3, 2020 BBM EARLY VOTES EV PROV EV ED PROV. ED VOTES TOTAL VOTES ED COUNTED COUNTED COUNTED COUNTED 3 COUNTED 4 GENERAL ELECTION COUNTED COUNTED COUNTED EV PROV ED PROV. COMBINED RESULTS 247 2647 REJECTED 17 2897 733 REJECTED 19 737 3634 EARLY COMBINED BBM EV EV PROV VOTING ED ED PROV TOTALED TOTAL TOTALS DONALD J. TRUMP/MICHAEL R. PENCE 147 2109 1 2257 552 3 555 2812 JOSEPH R. BIDEN/KAMALA D. HARRIS 95 499 2 596 161 0 161 757 JO JORGENSEN/JEREMY " SPIKE " COHEN 3 20 0 23 10 0 10 33 HOWIE HAWKINS/ANGELA WALKER 0 3 0 3 6 1 7 10 PRESIDENT R. BODDIE/ERIC C. STONEHAM 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 f- iE 0 PRIAN CARROLL/AMAR PATEL 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 u~ TODD CELLA/TIMCELLA ~ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 iE 0 i JESSE CUELLAR/JIMMY MONREAL 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 TOM HOEFLING/JIMMY MONREAL 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 GLORIA LA RIVA/LEONARD PELTIER 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ABRAM LOEB/JENNIFER JAIRALA 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ROBERT MORROW/ANNE BECKETT 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 KASEY WELLS/RACHEL WELLS 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 JOHN CORNYN 154 2062 1 2217 511 3 514 2731 MARY "MJ" HEGAR 85 464 2 551 163 0 163 714 KERRY DOUGLAS MCKENNON 1 46 0 47 16 0 16 63 DAVID B. -

Judge – Criminal District Court

NONPARTISAN ELECTION MATERIAL VOTERS GUIDE LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS OF HOUSTON EDUCATION FUND NOVEMBER 6, 2018 • GENERAL ELECTION • POLLS OPEN 7AM TO 7PM INDEX THINGS VOTERS United States Senator . 5. SHOULD NOW United States Representative . .5 K PHOTO ID IS REQUIRED TO VOTE IN PERSON IN ALL TEXAS ELECTIONS Governor . .13 Those voting in person, whether voting early or on Election Day, will be required to present a photo Lieutenant Governor . .14 identification or an alternative identification allowed by law. Please see page 2 of this Voters Guide for additional information. Attorney General . 14. LWV/TEXAS EDUCATION FUND EARLY VOTING PROVIDES INFORMATION ON Comptroller of Public Accounts . 15. Early voting will begin on Monday, October 22 and end on Friday, November 2. See page 12 of this Voters CANDIDATES FOR U.S. SENATE Guide for locations and times. Any registered Harris County voter may cast an early ballot at any early voting Commissioner of General Land Office . .15 AND STATEWIDE CANDIDATES location in Harris County. Our thanks to our state organization, Commissioner of Agriculture . 16. the League of Women Voters of VOTING BY MAIL Texas, for contacting all opposed Railroad Commissioner . 16. Voters may cast mail ballots if they are at least 65 years old, if they will be out of Harris County during the candidates for U.S. Senator, Supreme Court . .17 Early Voting period and on Election Day, if they are sick or disabled or if they are incarcerated but eligible to Governor, Lieutenant Governor, vote. Mail ballots may be requested by visiting harrisvotes.com or by phoning 713-755-6965. -

San Jacinto Largest Floor Plates in Austin Cbd Under Construction

SAN1836 JACINTO 230,609 RSF DELIVERING Q1 2021 1836 SAN JACINTO LARGEST FLOOR PLATES IN AUSTIN CBD UNDER CONSTRUCTION Uniquely located within the Capitol Complex, adjacent to the bustling Innovation and Medical Districts. 1836 SAN JACINTO CONTENTS CLICK ICON TO NAVIGATE AN AUTHENTIC AUSTIN EXPERIENCE WITH ABUNDANT ON-SITE AND WALKABLE AMENITIES LOCATION REGIONAL AERIAL VIEW MOBILITY INTERSECTION OF DELL MEDICAL, AREA DEVELOPMENT UT, CAPITOL COMPLEX & INNOVATION DISTRICT CAPITOL COMPLEX AMENITIES ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT LARGEST FLOORPLATES WITHIN THE CBD FOOD & DRINKS OFFERING UNPARALLELED VIEWS GREENSPACE HOSPITALITY 1836 SAN JACINTO OFF-SET CORE DESIGN OVERVIEW DELIVERING EFFICIENT INTERIOR SPACE PROGRAMMING FEATURES GROUND FLOOR PLAN TYPICAL FLOOR PLAN TERRACE FLOOR PLAN EXTENSIVE 9TH FLOOR CONFERENCE CENTER & EVENT SPACE CONTACT FEATURING AN OUTDOOR TERRACE INFORMATION © April 25, 2019. CBRE. All Rights Reserved. INTERSECTION 1 OF INNOVATION Pflugerville 1836 SAN JACINTO UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS Lake Travis W 17 MLK The Jr. 16 JUDGE’S Blvd En The f Domain ie HILL ld Rd W Arboretum 17th 18361836 SAN SAN JACINTOJACINTO St d Lake Travis Jr. Blv E MLK W d 1 v 5th l St B o t n i UPTOWN c MEDICAL t a S J n d n n v a l CAPITOL y S L B 20 r COMPLEX 360 W W 1 ma 2th a St 16 L Bridge o SH-130 i N n o t CENTRAL & Hwy 290 n W WATERLOO HEALTH A 10th PARK West Lake 9 n St th St a E 12 Highland S t S WEST a c W a 5th END v St W CATALYST TO EMERGING DISTRICT 6th La St W AUSTIN, TX 8 7th Mueller St CONGRESS Ideally situated between the University MARKET INNOVATION e v A E W t 1 5 s 1 of Texas, Dell Medical School and Tex- Innovation th S S th S t y t es t r i in District ng r as Capitol, 1836 San Jacinto is well po- WAREHOUSE o T W C SEAHOLM 3r d St Downtown E sitioned to be the employment catalyst W C 7th Austin esa CONVENTION St r Cha Austin ve within Austin’s Innovation District. -

Bush Artist Fellows

Bush Artist Fellows AY_i 1/14/03 10:05 AM Page i Bush Artist Fellows AY 1-55 1/14/03 10:07 AM Page 1 AY 1-55 1/14/03 10:07 AM Page 2 Bush Artist Fellows CHOREOGRAPHY MULTIMEDIA PERFORMANCE ART STORYTELLING M. Cochise Anderson Ananya Chatterjea Ceil Anne Clement Aparna Ramaswamy James Sewell Kristin Van Loon and Arwen Wilder VISUAL ARTS: THREE DIMENSIONAL Davora Lindner Charles Matson Lume VISUAL ARTS: TWO DIMENSIONAL Arthur Amiotte Bounxou Chanthraphone David Lefkowitz Jeff Millikan Melba Price Paul Shambroom Carolyn Swiszcz 2 AY 1-55 1/14/03 10:07 AM Page 3 Bush Artist Fellowships stablished in 1976, the purpose of the Bush Artist Fellowships is to provide artists with significant E financial support that enables them to further their work and their contributions to their communi- ties. An artist may use the fellowship in many ways: to engage in solitary work or reflection, for collabo- rative or community projects, or for travel or research. No two fellowships are exactly alike. Eligible artists reside in Minnesota, North and South Dakota, and western Wisconsin. Artists may apply in any of these categories: VISUAL ARTS: TWO DIMENSIONAL VISUAL ARTS: THREE DIMENSIONAL LITERATURE Poetry, Fiction, Creative Nonfiction CHOREOGRAPHY • MULTIMEDIA PERFORMANCE ART/STORYTELLING SCRIPTWORKS Playwriting and Screenwriting MUSIC COMPOSITION FILM • VIDEO Applications for all disciplines will be considered in alternating years. 3 AY 1-55 1/14/03 10:07 AM Page 4 Panels PRELIMINARY PANEL Annette DiMeo Carlozzi Catherine Wagner CHOREOGRAPHY Curator of -

Download Report

July 15th Campaign Finance Reports Covering January 1 – June 30, 2021 STATEWIDE OFFICEHOLDERS July 18, 2021 GOVERNOR – Governor Greg Abbott – Texans for Greg Abbott - listed: Contributions: $20,872,440.43 Expenditures: $3,123,072.88 Cash-on-Hand: $55,097,867.45 Debt: $0 LT. GOVERNOR – Texans for Dan Patrick listed: Contributions: $5,025,855.00 Expenditures: $827,206.29 Cash-on-Hand: $23,619,464.15 Debt: $0 ATTORNEY GENERAL – Attorney General Ken Paxton reported: Contributions: $1,819,468.91 Expenditures: $264,065.35 Cash-on-Hand: $6,839,399.65 Debt: $125,000.00 COMPTROLLER – Comptroller Glenn Hegar reported: Contributions: $853,050.00 Expenditures: $163,827.80 Cash-on-Hand: $8,567,261.96 Debt: $0 AGRICULTURE COMMISSIONER – Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller listed: Contributions: $71,695.00 Expenditures: $110,228.00 Cash-on-Hand: $107,967.40 The information contained in this publication is the property of Texas Candidates and is considered confidential and may contain proprietary information. It is meant solely for the intended recipient. Access to this published information by anyone else is unauthorized unless Texas Candidates grants permission. If you are not the intended recipient, any disclosure, copying, distribution or any action taken or omitted in reliance on this is prohibited. The views expressed in this publication are, unless otherwise stated, those of the author and not those of Texas Candidates or its management. STATEWIDES Debt: $0 LAND COMMISSIONER – Land Commissioner George P. Bush reported: Contributions: $2,264,137.95 -

Texas on the Mexican Frontier

Texas on the Mexican Frontier Texas History Chapter 8 1. Mexican Frontier • Texas was vital to Mexico in protecting the rest of the country from Native Americans and U.S. soldiers • Texas’ location made it valuable to Mexico 2. Spanish Missions • The Spanish had created missions to teach Christianity to the American Indians • The Spanish also wanted to keep the French out of Spanish-claimed territory 3. Empresarios in Texas • Mexico created the empresario system to bring new settlers to Texas • Moses Austin received the first empresario contract to bring Anglo settlers to Texas. 4. Moses Austin Moses Austin convinced Mexican authorities to allow 300 Anglo settlers because they would improve the Mexican economy, populate the area and defend it from Indian attacks, and they would be loyal citizens. 5. Moses Austin His motivation for establishing colonies of American families in Texas was to regain his wealth after losing his money in bank failure of 1819. He met with Spanish officials in San Antonio to obtain the first empresario contract to bring Anglo settlers to Texas. 6. Other Empresarios • After Moses Austin death, his son, Stephen became an empresario bring the first Anglo-American settlers to Texas • He looked for settlers who were hard- working and law abiding and willing to convert to Catholicism and become a Mexican citizen • They did NOT have to speak Spanish 7. Other Empresarios • His original settlers, The Old Three Hundred, came from the southeastern U.S. • Austin founded San Felipe as the capital of his colony • He formed a local government and militia and served as a judge 8. -

About Austin

Discover Austin City… no Limits! sponsor or endorser of SAA. ustin sustains many vibrant cultures and subcultures flourishing Downtown Austin looking across Lady Bird Lake. in a community that allows room for new ideas. The beauty of our (Lower Colorado River Authority) A green spaces, the luxury of a recreational lake in the middle of the city, historic downtown architecture blending with soaring new mixed-use high rises, and a warm climate provide inspiration and endless activities for citizens and visitors. BUILDINGS AND LANDMARKS If you haven’t heard the city’s unofficial motto yet, chances are you will In 1845, Austin became a state capital when the United States annexed the soon after arriving – “Keep Austin Weird” – a grassroots, underground Republic of Texas. The current capitol building was completed in 1888 on mantra that’s filtered upward, encouraging individuality and originality in an area of high ground, replacing the previous one that had burned with an every form. It’s an apt phrase, since from its beginnings Austin has imposing Renaissance Revival native pink granite and limestone structure, embodied an independent, unconventional spirit. the largest state capitol building in the nation. The dome is topped by the Goddess of Liberty, a zinc statue of a woman holding aloft a gilded Lone Star. From many vantage points downtown there are unobstructed views of the Capitol, planned for and protected by state law. Visitors are free to explore EARLY AUSTIN the beautifully maintained Capitol grounds and the building itself, where tour guides are available. The soaring interior of the Rotunda is a magnificent Austin began as the small, isolated frontier town of Waterloo, settled on the space and an excellent place to cool down during a summer walk. -

University of Dundee MASTER of PHILOSOPHY Changing British Perceptions of Spain in Times of War and Revolution, 1808 to 1838

University of Dundee MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Changing British Perceptions of Spain in Times of War and Revolution, 1808 to 1838 Holsman, John Robert Award date: 2014 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Changing British Perceptions of Spain in Times of War and Revolution, 1808 to 1838 John Robert Holsman 2014 University of Dundee Conditions for Use and Duplication Copyright of this work belongs to the author unless otherwise identified in the body of the thesis. It is permitted to use and duplicate this work only for personal and non-commercial research, study or criticism/review. You must obtain prior written consent from the author for any other use. Any quotation from this thesis must be acknowledged using the normal academic conventions. It is not permitted to supply the whole or part of this thesis to any other person or to post the same on any website or other online location without the prior written consent of the author. -

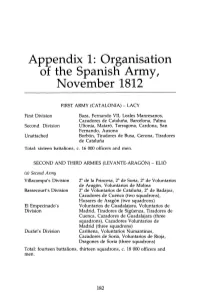

Appendix 1: Organisation of the Spanisn Army, November 1812

Appendix 1: Organisation of the Spanisn Army, November 1812 FIRST ARMY (CATALONlA) - LACY First Division Baza, Fernando VII, Leales Manresanos, Cazadores de Catalufla, Barcelona, Palma Second Division Ultonia, Matar6, Tarragona, Cardona, San Fernando, Ausona Unattached Borb6n, Tiradores de Busa, Gerona, Tiradores de Catalufla Total: sixteen battalions, c. 16 000 officers and men. SECOND AND THIRD ARMIES (LEV ANTE-ARAGON) - EUO (a) Second Army Villacampa' s Division 2° de la Princesa, 2° de Soria, 2° de Voluntarios de Arag6n, Voluntarios de Molina Bassecourt' s Division 2° de Voluntarios de Catalufla, 2° de Badajoz, Cazadores de Cuenca (two squadrons), Husares de Arag6n (two squadrons) EI Empecinado' s Voluntarios de Guadalajara, Voluntarios de Division Madrid, Tiradores de Sigüenza, Tiradores de Cuenca, Cazadores de Guadalajara (three squadrons), Cazadores Voluntarios de Madrid (three squadrons) Duran' s Division Cariflena, Voluntarios Numantinos, Cazadores de Soria, Voluntarios de Rioja, Dragones de Soria (three squadrons) Total: fourteen battalions, thirteen squadrons, c. 18 000 officers and men. 182 Appendix 1 183 (h) Third Army Vanguard - Freyre 1er de Voluntarios de la Corona, 1er de Guadix, Velez Malaga, Carabinieros Reales (one squadron), 1er Provisional de Linea (three squadrons), 2° Provisional de Linea (three squadrons), 1er Provisional de Dragones, (three squadrons), 2° Provisional de Dragones (three squadrons), 1er Provisional de Husares (two squadrons) Roche' s Division Voluntarios de Alicante, Canarias, Chinchilla, Cazadores de Valencia, Husares de Fernando VII (three squadrons) Montijo's Brigade 2° de Guardias Walonas, 1er de Badajoz, Cuenca Michelena' s Brigade 1er de Voluntarios de Arag6n, Tiradores de Cadiz, 2° de Mallorca Mijares' Brigade 1"' de Burgos, Alcazar de San Juan, BaHen, Lorca, Voluntarios de Jaen U na ttachedl garrisons Almansa, America, Alpujarras, Almeria, Cazadores de Jaen (one squadron), Cazadores de la Mancha (two squadrons) Total: twenty-two battalions, twenty-one squadrons, c.