The Inventions of African Identities and Languages: the Discursive and Developmental Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons from Burkina Faso's Thomas Sankara By

Pan-Africanism and African Renaissance in Contemporary Africa: Lessons from Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara By: Moorosi Leshoele (45775389) Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: Prof Vusi Gumede (September 2019) DECLARATION (Signed) i | P a g e DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to Thomas Noel Isadore Sankara himself, one of the most underrated leaders in Africa and the world at large, who undoubtedly stands shoulder to shoulder with ANY leader in the world, and tall amongst all of the highly revered and celebrated revolutionaries in modern history. I also dedicate this to Mariam Sankara, Thomas Sankara’s wife, for not giving up on the long and hard fight of ensuring that justice is served for Sankara’s death, and that those who were responsible, directly or indirectly, are brought to book. I also would like to tremendously thank and dedicate this thesis to Blandine Sankara and Valintin Sankara for affording me the time to talk to them at Sankara’s modest house in Ouagadougou, and for sharing those heart-warming and painful memories of Sankara with me. For that, I say, Merci boucop. Lastly, I dedicate this to my late father, ntate Pule Leshoele and my mother, Mme Malimpho Leshoele, for their enduring sacrifices for us, their children. ii | P a g e AKNOWLEDGEMENTS To begin with, my sincere gratitude goes to my Supervisor, Professor Vusi Gumede, for cunningly nudging me to enrol for doctoral studies at the time when the thought was not even in my radar. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

CB 3 4 Engl Samedi 1.Pmd

CODESRIA Bulletin, Nos 3 & 4, 2008 Page 1 Editorial A Giant Has Moved On This 12th General Assembly is taking place exactly one year and Sociology Department at the University of Dar Es Salaam, Tan- nine months after the death of an illustrious member of zania before moving to The Hague as a Visiting Professor of CODESRIA, one most committed to the problematic of the pub- Social Anthropology of Development and Chairman of the Ru- lic sphere in Africa. Wednesday 28 March 2007 will go down as ral Development, Urban Development and Labour Studies a sad day among social researchers all over Africa and beyond. Programme at the Institute of Social Studies from 1972 to 1975. It was the day Professor Archibald Monwabisi Mafeje (fondly It was here that he met his wife and life-long companion, the known among friends, colleagues and admirers as Archie) passed Egyptian scholar and activist, Dr Shahida El Baz. In 1979, he away in Pretoria, in what was a most quiet exit that has left very joined the American University, in Cairo, as Professor of Sociol- many of us whom he touched directly or indirectly, in a state of ogy. Thereafter, he took up the post of Professor of Sociology sadness and anger. and Anthropology and Director of the Multidisciplinary Re- search Centre at the University of Namibia from 1992 to 1994. Archie Mafeje, the quintessential personality of science and Mafeje was also a senior fellow and visiting or guest professor one of the most versatile, extraordinary minds to emerge from at several other universities and research institutions in Africa, Africa was, in his days, a living legend in every sense. -

Ali a Mazrui on the Invention of Africa and Postcolonial Predicaments1

‘My life is One Long Debate’: Ali A Mazrui on the Invention of Africa and Postcolonial Predicaments1 Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni2 Archie Mafeje Research Institute University of South Africa Introduction It is a great honour to have been invited by the Vice-Chancellor and Rector Professor Jonathan Jansen and the Centre for African Studies at the University of the Free State (UFS) to deliver this lecture in memory of Professor Ali A. Mazrui. I have chosen to speak on Ali A. Mazrui on the Invention of Africa and Postcolonial Predicaments because it is a theme closely connected to Mazrui’s academic and intellectual work and constitute an important part of my own research on power, knowledge and identity in Africa. Remembering Ali A Mazrui It is said that when the journalist and reporter for the Christian Science Monitor Arthur Unger challenged and questioned Mazrui on some of the issues raised in his televised series entitled The Africans: A Triple Heritage (1986), he smiled and responded this way: ‘Good, [...]. Many people disagree with me. My life is one long debate’ (Family Obituary of Ali Mazrui 2014). The logical question is how do we remember Professor Ali A Mazrui who died on Sunday 12 October 2014 and who understood his life to be ‘one long debate’? More importantly how do we reflect fairly on Mazrui’s academic and intellectual life without falling into the traps of what the South Sudanese scholar Dustan M. Wai (1984) coined as Mazruiphilia (hagiographical pro-Mazruism) and Mazruiphobia (aggressive anti-Mazruism)? How do we pay tribute -

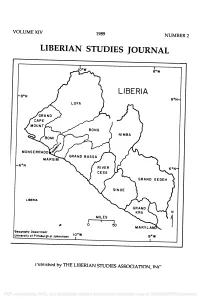

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL r 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI MARYLAND Geography Department 10 °W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 8oW 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. Elwood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Dalvan M. Coger Memphis State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Henrique F. Tokpa Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS THE LIBERIAN ECONOMY ON APRIL 1980: SOME REFLECTIONS 1 by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF AGRICULTURE AMONG THE KPELLE: KPELLE FARMING THROUGH KPELLE EYES 23 by John Gay "PACIFICATION" UNDER PRESSURE: A POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LIBERIAN INTERVENTION IN NIMBA 1912 -1918 ............ 44 by Martin Ford BLACK, CHRISTIAN REPUBLICANS: DELEGATES TO THE 1847 LIBERIAN CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION ........................ 64 by Carl Patrick Burrowes TRIBE AND CHIEFDOM ON THE WINDWARD COAST 90 by Warren L. -

BR-Beyond the Color Line

Kwesi Kwaa Prah. Beyond The Color Line: Pan-Africanist Disputations Selected Sketches, Letters, Papers And Reviews. Africa World Press, Inc., 1998, 188pp Kwesi Prah's book entitled Beyond the Color Line: Pan-Africanist Disputations: Selected Sketches, Letters, Papers and Reviews, accurately captures the contents of the book, which is largely a compendium of his Pan-Africanist philosophy and how it has shaped his life and scholarship over time. To begin, Prah provides a bio-sketch of his impressive background which includes his secondary education at the well-known Achimota School during which the struggle for Ghana's independence was underway. At a tender age of 25, while a student in Amsterdam he provided a space in his house for "the Medical Committee Angola which was supplying medicines for the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLN'(xii). While a lecturer at Heidelberg University in the late 1960s, Prah was elected the Secretary General of Ghana National Students Organization. Thereafter, he returned to Accra where he provided resources for displaced Zimbabwe children and South West Africa Peoples Organization (SWAPO). In the mid 1970s he accepted teaching positions at the University of Zambia, Juba University, Sudan and University of Botswana where he taught and operated underground in various activities in support of African resistance in South Africa. Like Du Bois, Makonnen, Nkrumah, Padmore among others whom Prah very deeply admired, he has devoted his entire life for African emancipation both on the continent and in the diaspora. He has also shown an active concern for the emancipation of other repressed people in Asia and South America. -

1 REITH LECTURES 1979: the African Condition Ali Mazrui

REITH LECTURES 1979: The African Condition Ali Mazrui Lecture 1: The Garden of Eden in Decay TRANSMISSION: 7 November 1979 – Radio 4 In the first Reith Lectures to be focused primarily on Africa, in 1961, Dame Margery Perham, the Oxford historian, decided to use a metaphor from accounting. She attempted a ‘colonial reckoning’, a kind of balance sheet of the costs and benefits of the colonial experience for both the colonised and the imperial powers. My own metaphor for these lectures is from the medical field. It is as if I were a doctor and Africa had come to me for a comprehensive medical examination on the eve of a particular anniversary. The most important century in Africa’s relations with Europe has been from the 1880s to the 1980s. It was from the 1880s that the map of Africa began to acquire more decisively the different flag colours of the occupation powers of Europe. Let us assume Africa has come to my clinic for varied medical tests on the eve of the 100th anniversary of Europe’s rape of her body and her possessions. I have therefore called this series of lectures The African Condition for two major reasons. One is diagnostic. To some extent this series is about Africa’s aches and pains: what is Africa’s state of health after 100 years of intense interaction with Europe? I also chose the title because it echoed the philosophical phrase ‘the human condition’. I want to examine the state of Africa partly as a way of measuring the state of the world. -

Intellectual Contributions of John Glover Jackson, an African

ABSTRACT AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES USHER, C. ANTHONY B.S., VIRGINIA STATE UNIVERSITY, 1991 EXPLORING THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF JOHN G. JACKSON TO AFRICAN HISTORIOGRAPHY Advisor: Dr. Keith E. Baird Thesis dated May, 1994 This thesis offers a comprehensive examination of the intellectual contributions of John Glover Jackson, an African American historian. Jackson, similiar to many other African American scholars, is self trained in the field of African history. This self training is a crucial element in this presentation for it is an attempt to present the autodidact's efforts and contributions as valid. This attempt reviews the archeological, anthropological, and cultural evidence presented by Jackson relating to his interpretations of man, God, and civilization. The methodology utilized in this research consists mainly of examining secondary data. Primary materials include interviews, video recordings, and recorded lectures. Critiques of the scholarly content of these materials are included in the assessment of Jackson's work. Iconographic, linguistic and ethnological evidence will be presented as interpreted by Jackson. The findings demonstrate that Jackson's contributions were virtually ignored. The reasons for this disregard are several. The dissenting nature of his presentation, his atheist reasoning and his lack of diplomacy contributed to his neglect. The results of this study carry wide reaching implications in the different fields of historical research. An Important finding, for example, is that formal university training is not an absolute prerequisite in the writing of history. Of greater significance is the evidence presented and the integrity of the historian's scholarship. The autodidact and the formally trained scholar have much to offer historiography. -

(504) 615-9018 [email protected] EDUC

ROBERT ST. MARTIN WESTLEY P.O. Box 4082 New Orleans, LA 70178 Work: (504) 862-8801 Home: (504) 615-9018 [email protected] EDUCATION Yale University, New Haven, CT Ph.D. in Philosophy, May 1993 M.Phil., May 1987; M.A., December 1986 Dissertation, "FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT JURISPRUDENCE: RACE AND THE RIGHTS OF GROUPS." Boalt Hall School of Law University of California, Berkeley J.D., May 1992 President, Boalt Hall Student Association Member, Black Law Student Association Northwestern University, Evanston, IL B.A. in Philosophy with Honors Distinction, 1984 Phi Beta Kappa Editor and Co-Founder of Nous TEACHING EXPERIENCE Tulane University School of Law New Orleans, LA 1995-present Louisiana Outside Counsel Health and Ethic Foundation (LOCHEF) Professor in Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility. Lecture courses on Legal Profession, Fourteenth Amendment, Constitutional Criminal Procedure, and Transnational Legal Practice. Taught seminars on Critical Race Theory, Law and Literature and Aging Studies. DePaul University College of Law Chicago, IL Spring 2007 Visiting Professor of Law. Lecture course on Legal Profession. Department of Ethnic Studies, University of California San Diego, CA 1992-93 Research Fellow/Lecturer. Taught seminar on Critical Race Theory. Lectured on Law and Minority Rights, and Race and Public Policy. Department of Philosophy, Yale University New Haven, CT 1986-87 Teaching Assistant. Assisted philosophy department faculty and led discussions for undergraduate courses in the areas of classical philosophy and introductory ethics. 1 FELLOWSHIPS AND HONORS School of Law, Tulane University New Orleans, LA 2007 Louisiana Outside Counsel Health and Ethic Foundation Professorship in Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Humanities Research Institute University of California, Irvine 2003 Research Fellow School of Law, Tulane University New Orleans, LA 1996 The Order of the Coif Department of Philosophy, University of California San Diego, CA 1993-95 UC President's Postdoctoral Fellowship. -

Shared Journey

The Rockefeller Foundation, Human Capital, and Development in Africa the rockefeller foundation centennial series shared journey the rockefeller foundation, human capital, and development in africa By Kathryn Mathers, Ph.D. Innovation for the Next 100 Years Rockefeller Foundation Centennial Series Shared Journey Preface from Dr. Judith Rodin 14 Foreword – Archbishop Desmond Tutu 18 Introduction 22 1 Fighting Hookworm in Egypt 34 11 Public Health for the World 48 111 Promoting Understanding 64 1v Africa Advancing 84 v Turning Toward Postcolonial Africa 104 © 2013 by Rockefeller Foundation in this publication. Images held by the v1 Training Health Workers in 118 The Rockefeller Foundation Centennial Series Rockefeller Archive Center have been Foreword copyright Books published in the Rockefeller deemed to be owned by the Rockefeller the Congo and South Africa Desmond Tutu, 2013 Foundation Centennial Series provide Foundation unless we were able to All rights reserved. case studies for people around the determine otherwise. Specific permis- v11 Academic Explorations 134 world who are working “to promote the sion has been granted by the copyright Cover: well-being of humankind.” Three books holder to use the following works: Top: Photo by Anthony Pappone. highlight lessons learned in the fields v111 Champions of Higher Education 156 Getty Images. of agriculture, health, and philanthropy. Jonas Bendiksen: 2-3, 22, 62-63, Bottom: Photo by Image Source. Three others explore the Foundation’s 98-101, 190-191, 207, 208, 212, 213, 1x Apartheid and South Africa 178 Getty Images. work in Africa, Thailand, and the United 225, 244-245, 250 States. For more information about Antony Njuguna: 6-7, 17, 132-133, 214-215 Africa and the Green Revolution 192 Book design by Pentagram. -

African Diasporas: Toward a Global History Paul Tiyambe Zeleza

African Diasporas: Toward a Global History Paul Tiyambe Zeleza Editors' note: The following article is a slightly revised version of the Presi- dential Address delivered at the fifty-second Annual Meeting of the African Studies Association in New Orleans in 2009. Abstract: This article interrogates the development of African diaspora studies. Based a global research project that seeks to map out the dispersals of African peo- ples in all the major regions of the world, compare the processes of diasporization, and examine the patterns of diaspora engagements, it offers a vigorous critique of the hegemonous Afro-Atlantic model in African diaspora studies. It focuses on two critical challenges that students of African diasporas must confront: the terms of analysis that are adopted, and the problems of historical mapping. Over the past five years, I have traveled to different parts of the world in search of African diasporas for a project entitled "Africa and Its Diasporas: Dispersals and Linkages," which was generously funded by the Ford Foun- dation. The project took me to sixteen countries: four in continental South and North America (Brazil, Venezuela, Mexico, and Canada); four in the Caribbean (Trinidad, Haiti, Cuba, and the Bahamas); four in Europe (Ger- many, Britain, France, and Spain); and four in Asia (India, Qatar, Dubai, and Oman). This is what I would like to share with you in this presentation: my search for peoples of African descent and their histories, trying to de- cipher the threads that tie them together and distinguish them from one another. African Studies Review, Volume 53, Number 1 (April 2010), pp. -

Islam, Christianity, Traditional Religions and Power Politics in Northern Nigeria Since Pre-Islamic Period

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2019 Islam, Christianity, Traditional Religions and Power Politics in Northern Nigeria Since Pre-Islamic Period Emmanuel M. Abar Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Africana Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Islamic Studies Commons Recommended Citation Abar, Emmanuel M., "Islam, Christianity, Traditional Religions and Power Politics in Northern Nigeria Since Pre-Islamic Period" (2019). Dissertations. 1678. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1678 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT ISLAM, CHRISTIANITY, TRADITIONAL RELIGIONS, AND POWER POLITICS IN NORTHERN NIGERIA SINCE PRE-ISLAMIC PERIOD by Emmanuel Abar Adviser: Nicholas Miller ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: ISALM, CHRISTIANITY, TRADITIONAL RELIGIONS, AND POWER POLITICS IN NORTHERN NIGERIA SINCE PRE-ISLAMIC PERIOD Name of researcher: Emmanuel Abar Name and degree of faculty adviser: Nicholas Miller, PhD Date completed: August 2019 Problem Currently in Northern Nigeria, religious