" Copper, Borders and Nation-Building": the Katangese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zambia 30 September 2017

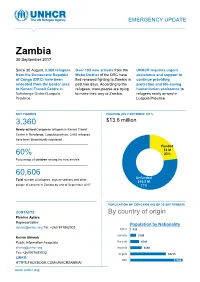

EMERGENCY UPDATE Zambia 30 September 2017 Since 30 August, 3,360 refugees Over 100 new arrivals from the UNHCR requires urgent from the Democratic Republic Moba District of the DRC have assistance and support to of Congo (DRC) have been fled renewed fighting to Zambia in continue providing relocated from the border area past two days. According to the protection and life-saving to Kenani Transit Centre in refugees, more people are trying humanitarian assistance to Nchelenge District/Luapula to make their way to Zambia. refugees newly arrived in Province. Luapula Province. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (AS 2 OCTOBER 2017) 3,360 $13.6 million requested for Zambia operation Newly-arrived Congolese refugees in Kenani Transit Centre in Nchelenge, Luapula province. 2,063 refugees have been biometrically registered Funded $3 M 60% 23% Percentage of children among the new arrivals Unfunded XX% 60,606 [Figure] M Unfunded Total number of refugees, asylum-seekers and other $10.5 M people of concern in Zambia by end of September 2017 77% POPULATION OF CONCERN (AS OF 30 SEPTEMBER) CONTACTS By country of origin Pierrine Aylara Representative Population by Nationality [email protected] Tel: +260 977862002 Other 415 Somalia 3199 Kelvin Shimoh Public Information Associate Burundi 4749 [email protected] Rwanda 6130 Tel: +260979585832 Angola 18715 LINKS: DRC 27398 HTTPS:FACEBOOK.COM/UNHCRZAMBIA/ www.unhcr.org 1 EMERGENCY UPDATE > Zambia / 30 September 2017 Emergency Response Luapula province, northern Zambia Since 30 August, over 3,000 asylum-seekers from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have crossed into northern Zambia. New arrivals are reportedly fleeing insecurity and clashes between Congolese security forces FARDC and a local militia groups in towns of Pweto, Manono, Mitwaba (Haut Katanga Province) as well as in Moba and Kalemie (Tanganyika Province). -

Files, Country File Africa-Congo, Box 86, ‘An Analytical Chronology of the Congo Crisis’ Report by Department of State, 27 January 1961, 4

This is an Open Access document downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's institutional repository: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/113873/ This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted to / accepted for publication. Citation for final published version: Marsh, Stephen and Culley, Tierney 2018. Anglo-American relations and crisis in The Congo. Contemporary British History 32 (3) , pp. 359-384. 10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 file Publishers page: http://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 <http://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598> Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. This version is being made available in accordance with publisher policies. See http://orca.cf.ac.uk/policies.html for usage policies. Copyright and moral rights for publications made available in ORCA are retained by the copyright holders. CONTEMPORARY BRITISH HISTORY https://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 ARTICLE Congo, Anglo-American relations and the narrative of � decline: drumming to a diferent beat Steve Marsh and Tia Culley AQ2 AQ1 Cardiff University, UK� 5 ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The 1960 Belgian Congo crisis is generally seen as demonstrating Congo; Anglo-American; special relationship; Anglo-American friction and British policy weakness. Macmillan’s � decision to ‘stand aside’ during UN ‘Operation Grandslam’, espe- Kennedy; Macmillan cially, is cited as a policy failure with long-term corrosive efects on 10 Anglo-American relations. -

1957 Eado.E4

1957 eado.e4 OF THE SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST DENOMINATION 4 I. w A DIRECTORY OF The General Conference, World Divisions, Union and Local Conferences and Missions, Educational Institutions, Hospitals and Sanitariums, Publishing Houses, Periodicals, and Denominational Workers. Edited and Compiled by H. W. Klaser, Statistical Secretary. General Conference Published by REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON 12, D.C. PRINTED IN U.S.A. Contents Fundamental Beliefs of Seventh-day Adventists 4 Constitution and By-Laws 5 General Conference and Departments 10 Divisions: North American 21 Australasian 68 Central European 83 China 89 Far Eastern 90 Inter-American 107 Middle East 123 Northern European 127 South American 140 Southern African 154 Southern Asia 171 Southern European 182 Union of Socialist Soviet Republics 199 Institutions: Educational 200 Food Companies 253 Medical 257 Dispensaries and Treatment Rooms 274 Old People's Homes and Orphanages 276 Publishing Houses 277 Periodicals Issued 286 Statistical Tables 299 Countries Where S.D.A. Work is Established 301 Languages in Which Publications Are Issued 394 Necrology 313 Index of Institutional Workers 314 Directory of Workers 340 Special Days and Offerings for 1957 462 Advertisers 453 Preface A directory of the conferences, mission state-wide basis in 1870, and state Sabbath fields, and institutions connected with the school associations in 1877. The name, "Se- Seventh-day Adventist denomination is given venth-day Adventists," was chosen in 1860, in the following pages. Administrative and and in 1903 the denominational headquarters workers' lists have been furnished by the were moved from Battle Creek, Mich., to organizations concerned. In cases where cur- Washington, D.C. -

ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018

UNICEF ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018 Zambia Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Zambia/2017/Ayisi ©UNICEF REPORTING PERIOD: JANUARY - JUNE 2018 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 15,425 # of registered refugees in Nchelengue • As of 28 June 2018, a total of 15,425 refugees from the district Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) were registered at (UNHCR, Infographic 28 June 2018) Kenani transit centre in the Luapula Province of Zambia. • UNICEF and partners are supporting the Government of Zambia 79% to provide life-saving services for all the refugees in Kenani of registered refugees are women and transit centre and in the Mantapala permanent settlement area. children • More than half of the refugees have been relocated to Mantapala permanent settlement area. 25,000 • The set-up of basic services in Mantapala is drastically delayed # of expected new refugees from DRC in due to heavy rainfall that has made access roads impassable. Nchelengue District in 2018 • Discussions between UNICEF and the Government are under way to develop a transition and sustainability plan to ensure the US$ 8.8 million continuity of services in refugee hosting areas. UNICEF funding requirement UNICEF’s Response with Partners Funding Status 2018 UNICEF Sector Carry- forward Total Total amount: UNICEF Sector $0.2 m Funds received current Target Results* Target year: $2.5 m Results* Nutrition: # of children admitted for SAM 400 273 400 273 treatment Health: # of children vaccinated against 11,875 6,690 11,875 6,690 measles WASH: # of people provided with access to 15,000 9,253 25,000 15,425 Funding Gap: $6.1 m safe water =68% Child Protection: # of children receiving 5,500 3,657 9,000 4,668 psychosocial and/or other protection services Funds available include funding received for the current year as well as the carry-forward from the previous year. -

UNITED Nations Distr

UNITED NATiONS Distr. GENERAL SECURITY S/5053/Add.12 8 October 1962 COUNCIL ENGLISH ORIGINAL: ENGLISH/FRENCH REPORT TO THE SECRETARY-GENERAL FROM THE OFFICER-IN-CHARGE OF THE UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN THE CONGO ON DEVELOPMENTS RELATING TO THE APPLICATION OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTIONS OF 21 FEBRUARY AND 24 NOVEMBER 1961 A. Build-Up of Katangese Mercenary Strength 1. In recent months) information has been received from various sources about a bUild-up in the strength of the Katanga armed forces) including the continued presence and some influx of foreign mercenaries. 2. It will be recalled that after the Kitona Declaration) signed on 21 December 1961 (S/5038 L Mr. Tshombe) President of the province of Katanga) made it clear to United Nations officials that he proposed to seek a solution to the mercenary problem "once and for all". This undertaking was put in writing in a letter dated 26 January 1962 to the United Nations representative in Elisabethville (S/5053/Add.3) Annex I)) and was repeated in a second letter dated 15 February 1962. 3. However) in spite of this and further declarations of Katangese spokesmen along the same lines as the above-mentioned letters) evidence ''las forthcon,ing to United. Nations authorities that in fact the pledge with regard to the elimination of mercenaries from Katanga was not being kept. 4. The ONUC-Katanga Joint Corrmissions on mercenaries) set up to certify that all foreign mercenaries had left Katanga in conformity with Mr. Tshombe's decision) visited Jadotville and Kipushi on 9 February 1962) and Kolwezi and Bunkeya on 21--23 February. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo

COMMUNICABLE DISEASE TOOLKIT PPPRRROOOFFFIIILLLEEE AAA NNN NNN EEE XXX EEE SSS Democratic Republic of the Congo WHO Communicable Disease Working Group on Emergencies WHO Regional Office for Africa WHO Office, Kinshasa COMMUNICABLE DISEASE TOOLKIT WHO/CDS/2005.36a PPRROOFFIILLEE Democratic Republic of the Congo WHO Communicable Disease Working Group on Emergencies WHO Regional Office for Africa WHO Office, Kinshasa © World Health Organization 2005 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by WHO to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication. -

Questions Concerning the Situation in the Republic of the Congo (Leopoldville)

QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE SITUATION IN THE CONGO (LEOPOLDVILLE) 57 QUESTIONS RELATING TO Guatemala, Haiti, Iran, Japan, Laos, Mexico, FUTURE OF NETHERLANDS Nigeria, Panama, Somalia, Togo, Turkey, Upper NEW GUINEA (WEST IRIAN) Volta, Uruguay, Venezuela. A/4915. Letter of 7 October 1961 from Permanent Liberia did not participate in the voting. Representative of Netherlands circulating memo- A/L.371. Cameroun, Central African Republic, Chad, randum of Netherlands delegation on future and Congo (Brazzaville), Dahomey, Gabon, Ivory development of Netherlands New Guinea. Coast, Madagascar, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, A/4944. Note verbale of 27 October 1961 from Per- Togo, Upper Volta: amendment to 9-power draft manent Mission of Indonesia circulating statement resolution, A/L.367/Rev.1. made on 24 October 1961 by Foreign Minister of A/L.368. Cameroun, Central African Republic, Chad, Indonesia. Congo (Brazzaville), Dahomey, Gabon, Ivory A/4954. Letter of 2 November 1961 from Permanent Coast, Madagascar, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Representative of Netherlands transmitting memo- Togo, Upper Volta: draft resolution. Text, as randum on status and future of Netherlands New amended by vote on preamble, was not adopted Guinea. by Assembly, having failed to obtain required two- A/L.354 and Rev.1, Rev.1/Corr.1. Netherlands: draft thirds majority vote on 27 November, meeting resolution. 1066. The vote, by roll-call was 53 to 41, with A/4959. Statement of financial implications of Nether- 9 abstentions, as follows: lands draft resolution, A/L.354. In favour: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, A/L.367 and Add.1-4; A/L.367/Rev.1. Bolivia, Congo Brazil, Cameroun, Canada, Central African Re- (Leopoldville), Guinea, India, Liberia, Mali, public, Chad, Chile, China, Colombia, Congo Nepal, Syria, United Arab Republic: draft reso- (Brazzaville), Costa Rica, Dahomey, Denmark, lution and revision. -

World Bank Document

I'lL (IDlYAF85RESTRICTED Vol. 2 Public Disclosure Authorized This report was prepored for use within the Bank and its affiliated organizations. Thny do not accept resmonsibility for its accuracy or completeness. The report may not be published nor may it be quoted as representing their views. INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Public Disclosure Authorized ~~ ~~ A ~?,f T-.7¶~T-hT T T T e fVt% 'T-Tr 1 - 7Tf1C ijfL1V1,.JIjk-n1 I I%- rklr U Jir1 L "XU1~ THE CONGO'S ECONOMY: EVOLUTION AND PROSPECTS. (in three volumes) ,Tr/T TT'XK7' TT Public Disclosure Authorized AGRICULTURE Africa Depaimen Public Disclosure Authorized -Africa Depa.rtment .CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS AND UNITS Fiom November 6, 1.961 to November 9,. 1963 UnitnC^ngolese fra-. (GF) US$ CF 64 From November 9, 1963 to June 23, 1967 Unit - Congolese fianc (CF) US$ 1 = CF 180 (selinig rate) TTC4U 1 - Ct 150 (bilx,rr ;i Atter June 23, 1967 Unit - Zaire (Z) equals 1, 000 CF US$ 1 ZO. 5 ThE CONGO'S ECONOMY: EVOLUTION AND PROSPECTS VOLUME II - AGRICULTURE TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. SULDARY AMTD CONCLUSIONS i-iii I. General Setting ..................................... 1 Introduction ..................................... 1 The Structure of Agriculture ................................ 3 II. Recent Developments in Agriculture .......................... 6 III. Agricultural Sorvicos and Prices ............................ 11 Organization and Staffing ................................... 11 Training and Research ................... 12 Incentives: -

Masterproef Maxim Veys 20055346

Universiteit Gent – Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Race naar Katanga 1890-1893. Een onderzoek naar het organisatorische karakter van de expedities in Congo Vrijstaat 1890-1893. Scriptie voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad van Master in de Geschiedenis Vakgroep Nieuwste Geschiedenis Academiejaar: 2009-2010 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Eric Vanhaute Maxim A. Veys Dankwoord Deze thesis was een werk van lange adem. Daarom zou ik graag mijn dank betuigen aan enkele mensen. Allereerst zou ik graag mijn promotor, Prof. Dr. Eric Vanhaute, willen bedanken voor de bereidheid die hij had om mij te begeleiden bij dit werk. In het bijzonder wil ik ook graag Jan-Frederik Abbeloos, assistent op de vakgroep, bedanken voor het aanleveren van het eerste idee en interessante extra literatuur, en het vele geduld dat hij met mij heeft gehad. Daarnaast dien ik ook mijn ouders te bedanken. In de eerste plaats omdat zij mij de kans hebben gegeven om deze opleiding aan te vatten, en voor de vele steun in soms lastige momenten. Deze scriptie mooi afronden is het minste wat ik kan doen als wederdienst. Ook het engelengeduld van mijn vader mag ongetwijfeld vermeld worden. Dr. Luc Janssens en Alexander Heymans van het Algemeen Rijksarchief wens ik te vermelden voor hun belangrijke hulp bij het recupereren van verloren gewaande bronnen, cruciaal om deze verhandeling te kunnen voltooien. Ik wil ook Sara bedanken voor het nalezen van mijn teksten. Maxim Veys 2 INHOUDSOPGAVE Voorblad 1 Dankwoord 2 Inhoudsopgave 3 I. Inleiding 4 II. Literatuurstudie 13 1. Het nieuwe imperialisme 13 2. Het Belgische “imperialisme” 16 3. De Onafhankelijke Congostaat. -

The Political Ecology of a Small-Scale Fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia

Managing inequality: the political ecology of a small-scale fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia Bram Verelst1 University of Ghent, Belgium 1. Introduction Many scholars assume that most small-scale inland fishery communities represent the poorest sections of rural societies (Béné 2003). This claim is often argued through what Béné calls the "old paradigm" on poverty in inland fisheries: poverty is associated with natural factors including the ecological effects of high catch rates and exploitation levels. The view of inland fishing communities as the "poorest of the poorest" does not imply directly that fishing automatically lead to poverty, but it is linked to the nature of many inland fishing areas as a common-pool resources (CPRs) (Gordon 2005). According to this paradigm, a common and open-access property resource is incapable of sustaining increasing exploitation levels caused by horizontal effects (e.g. population pressure) and vertical intensification (e.g. technological improvement) (Brox 1990 in Jul-Larsen et al. 2003; Kapasa, Malasha and Wilson 2005). The gradual exhaustion of fisheries due to "Malthusian" overfishing was identified by H. Scott Gordon (1954) and called the "tragedy of the commons" by Hardin (1968). This influential model explains that whenever individuals use a resource in common – without any form of regulation or restriction – this will inevitably lead to its environmental degradation. This link is exemplified by the prisoner's dilemma game where individual actors, by rationally following their self-interest, will eventually deplete a shared resource, which is ultimately against the interest of each actor involved (Haller and Merten 2008; Ostrom 1990). Summarized, the model argues that the open-access nature of a fisheries resource will unavoidably lead to its overexploitation (Kraan 2011). -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRapHY ARCHIVaL MaTERIaL National Archives of Malawi (MNA), Zomba. National Archives at Kew (Co.525 Colonial Office Correspondence). Society of Malawi Library, Blantyre. Malawi Section, University Library, Chancellor College, Zomba. PUBLISHED BOOKS aND ARTICLES Abdallah, Y.B. 1973. The Yaos (Chikala Cha Wayao). Ed. M. Sanderson. (Orig 1919). London: Cass. Adams, J.S. and T. McShane. 1992. The Myth of Wild Africa. New York: Norton. Allan, W. 1965. African Husbandman. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd. Alpers, E.A. 1969. Trade, State and Society Among the Yao in the Nineteenth Century J. Afr. History 10: 405–420. ———. 1972. The Yao of Malawi in B. Pachai (ed) The Early History of Malawi pp 168–178. London: Longmans. ———. 1973. Towards a History of Expansion of Islam in East Africa in T.O. Ranger and N. Kimambo (eds) The Historical Study of African Religion pp 172–201. London: Heinemann. ———. 1975. Ivory and Slaves in East-Central Africa. London: Heinemann. Anderson-Morshead, A.M. 1897. The History of the Universities Mission to Central Africa 1859-96. London: UNICA. Anker, P. 2001. Imperial Ecology: Environmental Order in the British Empire. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. © The Author(s) 2016 317 B. Morris, An Environmental History of Southern Malawi, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-45258-6 318 BiblioGraphy Ansell, W.F.H. and R.J. Dowsett. 1988. Mammals of Malawi: An Annoted Checklist and Atlas. St Ives: Trendrine Press. Antill, R.M. 1945. A History of Native Grown Tobacco Industry in Nyasaland Nyasaland Agric. Quart. J. 8: 49–65. Baker, C.A. 1961. A Note on Nguru Immigration to Nyasaland Nyasaland J. -

The Geography and Economic Development of British Central Africa: Discussion Author(S): Lewis Beaumont, Harry Johnston, Wilson Fox, J

The Geography and Economic Development of British Central Africa: Discussion Author(s): Lewis Beaumont, Harry Johnston, Wilson Fox, J. H. West Sheane, Clement Hill and Alfred Sharpe Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 39, No. 1 (Jan., 1912), pp. 17-22 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1778323 Accessed: 17-04-2016 17:44 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 134.129.182.74 on Sun, 17 Apr 2016 17:44:26 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms BRITISH CENTRAL AFRICA?DISCITSSION. 17 purely philanthropic in these matters?we do not enter upon such enter- prises with the sole view of benefiting the African: we have our own purposes to serve, but they must be served in such a way as to operate to the advantage of all. I have little hesitation in replying that our occupation has had the best results, and from all points of view. So far as our own interests are concerned we have opened up a promising part of Tropical .Africa.