Klahs, PC. 2014 the Vascular Flora of Steele Creek Park and A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RI Equisetopsida and Lycopodiopsida.Indd

IIntroductionntroduction byby FFrancisrancis UnderwoodUnderwood Rhode Island Equisetopsida, Lycopodiopsida and Isoetopsida Special Th anks to the following for giving permission for the use their images. Robbin Moran New York Botanical Garden George Yatskievych and Ann Larson Missouri Botanical Garden Jan De Laet, plantsystematics.org Th is pdf is a companion publication to Rhode Island Equisetopsida, Lycopodiopsida & Isoetopsida at among-ri-wildfl owers.org Th e Elfi n Press 2016 Introduction Formerly known as fern allies, Horsetails, Club-mosses, Fir-mosses, Spike-mosses and Quillworts are plants that have an alternate generation life-cycle similar to ferns, having both sporophyte and gametophyte stages. Equisetopsida Horsetails date from the Devonian period (416 to 359 million years ago) in earth’s history where they were trees up to 110 feet in height and helped to form the coal deposits of the Carboniferous period. Only one genus has survived to modern times (Equisetum). Horsetails Horsetails (Equisetum) have jointed stems with whorls of thin narrow leaves. In the sporophyte stage, they have a sterile and fertile form. Th ey produce only one type of spore. While the gametophytes produced from the spores appear to be plentiful, the successful reproduction of the sporophyte form is low with most Horsetails reproducing vegetatively. Lycopodiopsida Lycopodiopsida includes the clubmosses (Dendrolycopodium, Diphasiastrum, Lycopodiella, Lycopodium , Spinulum) and Fir-mosses (Huperzia) Clubmosses Clubmosses are evergreen plants that produce only microspores that develop into a gametophyte capable of producing both sperm and egg cells. Club-mosses can produce the spores either in leaf axils or at the top of their stems. Th e spore capsules form in a cone-like structures (strobili) at the top of the plants. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Notes on Some Species of Diphasiastrum

Preslia, Praha, 47: 232 - 240, 1975 Notes on some species of Diphasiastrum Poznamky k n~kterym druhum rodu Dipha11iaatrum Josef Holub HOLUB J. (1975): Notes on some species of Diphasiastrum. - Preslia, Praha, 47: 232- 240. Taxonomic and nomenclatural problems of some species of Diphasiastrum HOLUB are discussed. A special attention is pa.id to the interspecies D. / X / issleri and D. / x / zei leri. Original plants of D. / x / issleri correspond to the combination D. alpinum - D. complanatum. Plants corresponding to the combination D. alpinum - D. tristachyum have been collected in the ~umava Mts. Some taxa described from the subarctic regions of Europe and North America are shown to belong most probably to the neglected interspecies D. / x / zeileri. Botanical I nstitute, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, 25~ 43 Prithonice, Czecho.,lovakia. INTRODUCTION This is a second part of my study of the new genus Diphasiastrum (HOLUB 1975), which could not be published in this journal in its entirety. Notes on taxonomy and nomenclature are selected from materials gathered originally for my "Catalogue of Czechoslovak vascular plants". With regard to the character of that work the present observations summarize the results of my own studies and suggests problems to be studied in the future. OBSERVATIONS f!.iphasiastrum alpinum (L.) HOLUB Two varieties have been described in this species (both under the name Lycopodium alpi nttm L.): var. thellungii HERTER from Switzerland and var. planiramulosum TAKEDA from Japan. Both these taxa, especially the first one, require a taxonomic revision; the possibility cannot be exclu<led that they are conspecific with D. / x / issleri. -

Split Rock Trail Most Diverse Vegetation Types in North America

Species List Species List National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Color Species Habit Season Color Species Habit Season Section 2, ■ • Section 1 W Ambrosia dumosa (burrobush) S C Y Opuntia chlorotica (pancake cactus) C c Joshua Tree National Park W Brickellia atractyloides (pungent brickellia) S c Y Rhus aromatica (skunk bush) s C w Caulanthus cooperi (Cooper's caulanthus) A c Y Senegalia greggii (cat's claw acacia) s H % w Chaenacf/s srew'o('c/es (Esteve's pincushion) A c Y Senna armata (desert senna) s C, H w Cryptantha barbigera (bearded forget-me-not) A c Y Tetradymia stenolepis (Mojave cottonthorn) s H w Cryptantha nevadensis (Nevada forget-me-not) A c 0 Adenophyllum porophylloides (San Felipe dyssodia) SS C, H tv w Eriogonum davidsonii (Davidson's buckwheat) A c, H 0 Sphaeraicea ambigua (apricot mallow) p C V w Eriogonum fasciculatum (California buckwheat) S C, H p Allium parishii (Parish's onion) B C \ w Eriogonum wrightii (Wright's buckwheat) SS H p Cylindropuntia ramosissima (pencil cholla) c H t Section 4 w Euphorbia albomarginata (rattlesnake weed) A C, H I p Echinocereus engelmannii (hedgehog cactus) c C P- ♦ Section 31 w Galium stellatum (starry bedstraw) SS C p Krameria erecta (littieleaf ratany) s C W/P Giliastellata (stargiiia) A C P/W Mirabilis laevis (wishbone bush) p c w Lepidium lasiocarpum (white pepperweed) A c _PJ Opuntia basilaris (beavertai! cactus) c c N w Lycium andersonii (Anderson's boxthorn) S c p Stephanomeria exigua (small wirelettuce) A C,H A w Lydum cooperi (Cooper's boxthorn) s c p Stephanomeria parryi (Parry's wirelettuce) P c w Nolina parryi (Parry nolina) s c p IStephanomeria paudflora (brownplume wirelettuce) SS c 0 500 2000 Feet w Pectocarya recurvata (arched-nut comb-bur) A c Boechera xylopoda (bigfoot hybrid rockcress) P c 0 150 600 Meters w Pecfocarya serosa (round-nut comb-bur) A c Delphinium parishii (Parish's larkspur) P c See inside of guide for plants found in each section of this map. -

A Comparative Study of the Plants Used for Medicinal Purposes by the Creek and Seminoles Tribes

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 3-24-2010 A Comparative Study of the Plants Used for Medicinal Purposes by the Creek and Seminoles Tribes Kimberly Hutton University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Hutton, Kimberly, "A Comparative Study of the Plants Used for Medicinal Purposes by the Creek and Seminoles Tribes" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1665 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Comparative Study of the Plants Used for Medicinal Purposes by the Creek and Seminoles Tribes by Kimberly Hutton A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Cell Biology, Microbiology, and Molecular Biology College of Arts and Science University of South Florida Major Professor: Richard P.Wunderlin, Ph.D. Frederick Essig, Ph.D Brent Weisman, Ph.D Date of Approval: March 24, 2010 Keywords: ethnobotany, native, treatments, illness, Florida © Copyright 2010, Kimberly Hutton ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my major professor and advisor, Dr. Richard Wunderlin, for his support, guidance, knowledge and patience throughout this project. I would also like to thank Sarah Sanford for her editorial guidance. Thanks go to my friend and cheerleader, Laurie Walker, who kept me going with her encouragement and unwaivering support. -

INDEX for 2011 HERBALPEDIA Abelmoschus Moschatus—Ambrette Seed Abies Alba—Fir, Silver Abies Balsamea—Fir, Balsam Abies

INDEX FOR 2011 HERBALPEDIA Acer palmatum—Maple, Japanese Acer pensylvanicum- Moosewood Acer rubrum—Maple, Red Abelmoschus moschatus—Ambrette seed Acer saccharinum—Maple, Silver Abies alba—Fir, Silver Acer spicatum—Maple, Mountain Abies balsamea—Fir, Balsam Acer tataricum—Maple, Tatarian Abies cephalonica—Fir, Greek Achillea ageratum—Yarrow, Sweet Abies fraseri—Fir, Fraser Achillea coarctata—Yarrow, Yellow Abies magnifica—Fir, California Red Achillea millefolium--Yarrow Abies mariana – Spruce, Black Achillea erba-rotta moschata—Yarrow, Musk Abies religiosa—Fir, Sacred Achillea moschata—Yarrow, Musk Abies sachalinensis—Fir, Japanese Achillea ptarmica - Sneezewort Abies spectabilis—Fir, Himalayan Achyranthes aspera—Devil’s Horsewhip Abronia fragrans – Sand Verbena Achyranthes bidentata-- Huai Niu Xi Abronia latifolia –Sand Verbena, Yellow Achyrocline satureoides--Macela Abrus precatorius--Jequirity Acinos alpinus – Calamint, Mountain Abutilon indicum----Mallow, Indian Acinos arvensis – Basil Thyme Abutilon trisulcatum- Mallow, Anglestem Aconitum carmichaeli—Monkshood, Azure Indian Aconitum delphinifolium—Monkshood, Acacia aneura--Mulga Larkspur Leaf Acacia arabica—Acacia Bark Aconitum falconeri—Aconite, Indian Acacia armata –Kangaroo Thorn Aconitum heterophyllum—Indian Atees Acacia catechu—Black Catechu Aconitum napellus—Aconite Acacia caven –Roman Cassie Aconitum uncinatum - Monkshood Acacia cornigera--Cockspur Aconitum vulparia - Wolfsbane Acacia dealbata--Mimosa Acorus americanus--Calamus Acacia decurrens—Acacia Bark Acorus calamus--Calamus -

Ecophysiology of Four Co-Occurring Lycophyte Species: an Investigation of Functional Convergence

Research Article Ecophysiology of four co-occurring lycophyte species: an investigation of functional convergence Jacqlynn Zier, Bryce Belanger, Genevieve Trahan and James E. Watkins* Department of Biology, Colgate University, Hamilton, NY 13346, USA Received: 22 June 2015; Accepted: 7 November 2015; Published: 24 November 2015 Associate Editor: Tim J. Brodribb Citation: Zier J, Belanger B, Trahan G, Watkins JE. 2015. Ecophysiology of four co-occurring lycophyte species: an investigation of functional convergence. AoB PLANTS 7: plv137; doi:10.1093/aobpla/plv137 Abstract. Lycophytes are the most early divergent extant lineage of vascular land plants. The group has a broad global distribution ranging from tundra to tropical forests and can make up an important component of temperate northeast US forests. We know very little about the in situ ecophysiology of this group and apparently no study has eval- uated if lycophytes conform to functional patterns expected by the leaf economics spectrum hypothesis. To determine factors influencing photosynthetic capacity (Amax), we analysed several physiological traits related to photosynthesis to include stomatal, nutrient, vascular traits, and patterns of biomass distribution in four coexisting temperate lycophyte species: Lycopodium clavatum, Spinulum annotinum, Diphasiastrum digitatum and Dendrolycopodium dendroi- deum. We found no difference in maximum photosynthetic rates across species, yet wide variation in other traits. We also found that Amax was not related to leaf nitrogen concentration and is more tied to stomatal conductance, suggestive of a fundamentally different sets of constraints on photosynthesis in these lycophyte taxa compared with ferns and seed plants. These findings complement the hydropassive model of stomatal control in lycophytes and may reflect canaliza- tion of function in this group. -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY BIBLIOGRAPHY Ackerfield, J., and J. Wen. 2002. A morphometric analysis of Hedera L. (the ivy genus, Araliaceae) and its taxonomic implications. Adansonia 24: 197-212. Adams, P. 1961. Observations on the Sagittaria subulata complex. Rhodora 63: 247-265. Adams, R.M. II, and W.J. Dress. 1982. Nodding Lilium species of eastern North America (Liliaceae). Baileya 21: 165-188. Adams, R.P. 1986. Geographic variation in Juniperus silicicola and J. virginiana of the Southeastern United States: multivariant analyses of morphology and terpenoids. Taxon 35: 31-75. ------. 1995. Revisionary study of Caribbean species of Juniperus (Cupressaceae). Phytologia 78: 134-150. ------, and T. Demeke. 1993. Systematic relationships in Juniperus based on random amplified polymorphic DNAs (RAPDs). Taxon 42: 553-571. Adams, W.P. 1957. A revision of the genus Ascyrum (Hypericaceae). Rhodora 59: 73-95. ------. 1962. Studies in the Guttiferae. I. A synopsis of Hypericum section Myriandra. Contr. Gray Herbarium Harv. 182: 1-51. ------, and N.K.B. Robson. 1961. A re-evaluation of the generic status of Ascyrum and Crookea (Guttiferae). Rhodora 63: 10-16. Adams, W.P. 1973. Clusiaceae of the southeastern United States. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 89: 62-71. Adler, L. 1999. Polygonum perfoliatum (mile-a-minute weed). Chinquapin 7: 4. Aedo, C., J.J. Aldasoro, and C. Navarro. 1998. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sections Batrachioidea and Divaricata (Geraniaceae). Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 85: 594-630. Affolter, J.M. 1985. A monograph of the genus Lilaeopsis (Umbelliferae). Systematic Bot. Monographs 6. Ahles, H.E., and A.E. -

January 1958 the National HORTICULTUR .·\L Magazine

TIIE N A..TIONA..L ~GA'Z , INE 0 & JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY, INC. * January 1958 The National HORTICULTUR .·\L Magazine *** to accumulate, Increase, and disseminate horticultural information *** OFFICERS EDITOR STUART M. ARMSTRONG, PR ESIDENT B. Y. MORRISON Silver Spring, Maryland MANAGING EDITOR HENRY T. SKINNER, FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT Washington, D.C. JAM ES R . H ARLOW MRS. i'VAL TER DOUGLAS, SECON D VICE-PRESIDENT EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Chauncey, New York I/:;- Phoenix, Arizona i'VALTER H . HOD GE, Chairman EUGENE GRIFFITH, SECRETARY JOH N L. CREECH Takoma Pm'k, Maryland FREDERIC P. LEE MISS OLIVE E. WEA THERELL, TREASURER CONRAD B. LINK Olean, New York & W ashington, D.C. CURTIS IVIA Y DIRECTORS The National Horticultural Maga zine is the official publication of the Te?'ms Expiring 1958 American Horticultural Society and is Stuart lVI. Armstrong, Mm'yland iss ued four times a year during the John L. Creech, Maryland qu arter s commencing with J anuary, Mrs. Peggie Schulz, Min nesota April, July and October. It is devoted to the dissemination of knowledge in R. P. iJ\Thite, Dist?'ict of Columbia the sc ience and art of growing orna Mrs. H arry Wood, Pennsylvania mental plants, fruits, vegetables, and rela ted subjects. Original papers increasing the his· T erms Expiring 1959 torical, varietal, and cultural knowl Donovan S. Correll, T exas edges of plant materials of economic and aesthetic importance are wel Frederick VV. Coe, Mm'yland comed and will be published as early Miss Margaret C. Lancaster, MG1'yland as possible. The CHairman of the ~ di · Mrs. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

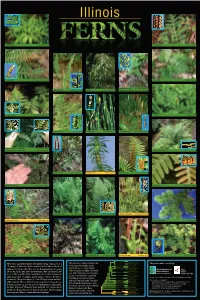

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Lycopodiaceae Clubmoss Family

Lycopodiaceae Page | 46 clubmoss family Upwards of 15 genera comprise this ancient family. Perennial herbs, they somewhat resemble coarse mosses. The solitary sporangia are borne either in a terminal strobilus or are axillary with leaves. Spores are of equal size. In Nova Scotia we have four genera. A. Rhizomes absent; upright stems clustered; axillary sporangia; spores pitted. Huperzia aa. Rhizomes present; upright shoots alternate; sporangia aggregated into B terminal strobili, spores with netlike pattern. B. Strobili on leafy peduncles; mainly of wetland habitats. Lycopodiella bb. Strobili sessile or on peduncles with remote scant leaves; mainly of C dry upland places. C. Tips of stems 5–12mm in diameter; leaves in 6 ranks or Lycopodium more; leaves bristly, free for most of their length, not scalelike. cc. Distal shoots 2–6mm in diameter; leaves in 4–6 ranks, Diphasiastrum strongly overlapping (scalelike) and appressed along the stem with only tips free. Diphasiastrum Holub There are 15–20 species worldwide; numerous hybrids are possible. Generally these clubmosses are northern or subarctic in distribution. Nova Scotia has four species. Rhizomes bear sparse leaves that are reduced to scales, rooting from the lower surfaces. Upright stems are flattened or angled, with 2–5 branches. Leaves are arranged in four ranks and of two sizes. Sporophylls are smaller than unspecialized leaves. 1-7 Lycopodiaceae Key to species A. Plants < 12 cm tall; strobili sessile. Diphasiastrum sitchense Page | 47 aa. Stems 8–50cm; strobili on peduncles. B B. Branches square or angled, bluish. D. tristachyum bb. Branches flat; green. C C. Lateral branches irregular, annual winter bud constrictions D. -

Exploring Lycopodiaceae Endophytes, Dendrolycopodium

EXPLORING LYCOPODIACEAE ENDOPHYTES, DENDROLYCOPODIUM SYSTEMATICS, AND THE FUTURE OF FERN MODEL SYSTEMS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science By Alaina Rousseau Petlewski May 2020 ©2020 Alaina Rousseau Petlewski i ABSTRACT This thesis consists of three chapters addressing disparate topics in seed-free plant biology. Firstly, I begin to describe the endophyte communities of lycophytes by identifying the culturable endophytes of five Lycopodiaceae species. Microbial endophytes are integral factors in plant evolution, ecology, and physiology. However, the endophyte communities of all major groups of land plants have yet to be characterized. Secondly, I begin to re-evaluate the systematics of a historically perplexing genus, Dendrolycopodium (Lycopodiaceae). Lastly, I assess the status of developing fern model systems and discuss possible future directions for this work. ii BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Alaina was born in 1995 near Dallas, TX, but was largely raised in central California. In high school, she developed a love of plants and chemistry. She graduated summa cum laude from Humboldt State University in 2017 with a B.S. in botany and minor in chemistry. After graduating from Cornell, she plans to move back to the West Coast. She aspires to find a way to combine her love of plants and admiration for the arts, have a garden, be kind, share her knowledge, and raise poodles with her partner. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor Fay-Wei Li and committee members Chelsea Specht and Robert Raguso, for their advisement on this work and for supporting me beyond my research pursuits by helping me to discover and act on what is right for me.